I first glitched in July 2018. I was living in Los Angeles, two months into housesitting a cousin's one-bedroom apartment. The sun oozed through the skylight above me like a bloody egg, staining the pages of the book in front of me. Without warning, I felt as if my entire body had been suffused with needles and warm cotton, a sensation both coarse and hot. I suddenly viewed everything at a distance, wielding my body like some ungainly, fleshy marionette. For three weeks, I watched the world pass by as if from the end of a tunnel.

That period of depersonalization-derealization disorder, resulting from what I eventually had diagnosed as PTSD, was essentially a glitch in my cognition. Unable to continue repressing a traumatic event that I had considered myself past, my mind overheated and crashed. While I was able to perform a hard reboot of my glitched system with access to the correct medications and doctors, the experience left me wary of the fallibility of my own cognition. I felt acutely aware of how our minds and bodies are just as susceptible to broken circuits and crossed wires as the machines that service them.

Our day-to-day encounters with glitch are both mundane and visually disruptive. We might consider the explosive fractals generated on a computer screen by unwanted malware, the abject torment of an NPC stuttering between two walls in a video game, or the universally dreaded blue screen of death. The glitch also predates digital media as a more general term for temporary malfunction or irregularity. The jamming of a piston in an assembly line, a misaligned hammer in a typewriter, or even the steady decay of an illuminated manuscript (as Curt Cloninger argues of The Book of Durrow, a text dating back to 680 A.D.) all operate as moments of glitch.1 As a moment of acute inconvenience, the glitch defies the pretense of seamlessness in the medium through which it emerges. Much like a difficult poem, the glitch encounter is one in which a previously transparent mode of information transmission splinters and stalls out, forcing the artifice of machinery, screen, or page to the forefront of our attention.

Glitch Art, which emerged in Chicago during the early aughts, attempted to mobilize the formal affordances of digital error to point toward the artifice of the interface. In a sense, Glitch Art operated adjacent to the practices we generally associate with both formally transgressive visual poetry — which fractures our experience of the page through spacing, misprinted or overlapped text — and collage to force consideration of the similar artifice of the page: what we encounter is not a smooth transmission of language, but an encounter with the medium through which language is being transmitted. Broken lines or machines also make apparent other, more overt, moments of material cultural error or malfunction. How might a "glitch" or illegible poem be nested within the necessary crip politic of malfunctioning minds?2 How can a vernacular of glitch recalibrate our assumptions of what a mind should or should not do and force us to reconsider what constitutes a "smooth" and "functioning" cognitive, digital, or lexical interface?

The genuine subversion of Glitch Art was remarkably short-lived. "Every form of glitch, whether breaking the flow or designed to look like it breaks the flow, will eventually become the new fashion," Rosa Menkman proclaims in her Glitch Studies Manifesto: "That is fate."3 A year before Menkman's pronouncement, Kanye West had released his music video for "Welcome to Heartbreak," a direct plagiarization of the digital practice of "datamoshing" (in which "I frames" randomize where new pixels are formed, fracturing the visual output of the image) pioneered by Paul B. Davis.4 As Davis himself writes: "It fucked my show up... the very language I was using to critique pop content from the outside was now itself a mainstream cultural reference."5

Whatever anti-normative force artists and researchers might have once ascribed to the glitch has, in the last decade, been thoroughly gentrified within popular culture as a vernacular form. When we open our iPhones, we are marketed VFX photo editing applications such as Glitché, complete with endorsements from Kylie Jenner, Travis Scott, Kim Kardashian, and Ariana Grande. On Instagram Stories, we can take selfies that are visually adjacent to Rosa Menkman's self-portrait databending (titled "A Vernacular of File Formats") with any of the application's hundreds of glitch filter options.6 For a few months in 2021, the "Glitch Challenge" became a viral trend on TikTok, with white, cis-het influencers popping and locking to Missy Elliot.7 Glitch today is less often a moment of genuine technological disruption than it is simply a source of commercial revenue. Or, as Kim Cascone suggests, "Glitch has become a genre tag on iTunes."8

Recently, we have seen a new surge of critical scholarship rehabilitating glitch not simply as a formalist technique but as an aesthetic mode that enables new investigation into how machinic failure intersects with various axes of identity.9 Most notable here is Legacy Russell's manifesto Glitch Feminism. According to Russell, glitch has become a distinctly minoritarian aesthetic largely due to its status as a metonym for digital illegibility. The glitch is a moment in which data becomes incapable of being read or classified by a computer, much as categories of race and gender often emerge when they are incapable of being categorized or assimilated by the State. Russell writes:

Errors, ever unpredictable, surface the unnamable, point toward a wild unknown. To become an error is to surrender to becoming unknown, unrecognizable, unnamed . . . But errors are fascinating in this way, as they often skirt control, being difficult to replicate and therefore difficult to reproduce for the sake of troubleshooting them out of existence. 10

It is worth noting that any minoritarian reading of the glitch was largely absent from the formation of glitch studies as a discipline. While some artists and scholars such as Jon Cates did attempt to historicize Glitch Art as a mode of anti-capitalist critique, an overwhelming majority of the scene was homogenously white, cis-gendered, and nondisabled.11

Disability, however, has yet to be included in that spectrum of identities which, when mediated through glitch, becomes both disruptive and illegible. This omission strikes me as odd. Glitch and disability share a similar aesthetic engagement with brokenness. Tobin Siebers famously defines "disability aesthetics" as that which "embraces beauty that seems by traditional standards to be broken, and yet it is not less beautiful, but more so, as a result."12 Siebers locates a disability in the fugitive history of vandalized art objects, such as the defacing of Michelangelo's Pietà, arguing that vandalization changes the art object's referential function and, more importantly, often "evoke the same feelings of suffering, revulsion, and pity aroused by people with injuries or disabilities, but they do so with an important difference. They divert the beholder's attention from the content to the form of the artwork."13 According to Siebers, vandalized art objects operate as both disabled images and images of disability, with the capacity to represent disability in a "rawer, more immediate, and more potent" form due to its transgression of the barrier between art and reality.14

We might make a similar rhetorical claim regarding the aesthetic and political stakes of the glitch artifact. The glitch marks the "breaking" of the interface, as body, mind, and machine are unable to fulfill the rigorous demands of their respective built environments. The glitch often seems resolutely broken and non-functional, the vigorous refusal of an interface to work as it should, yet in that refusal the glitch holds a certain abject beauty. Many of us have, at some point, been mesmerized by the psychedelic flickering of a stalled-out homepage, the neon, pixilated fractals of a broken screen. Various malware hacker cultures of the 1980s and 1990s, which favored jarring colors, enigmatic limericks, and punchy slogans, offer one such example of glitch vandalism. Early malware, intentionally or not, draws on the aesthetic vernacular and political ethos of détournement, the practice developed by the Letterist International (and more famously adapted by the Situationists) that involved the hijacking of media iconography and propaganda to elucidate their underlying ideologies. As objects of détournement, these early viruses commonly existed in the liminal space between prank and culture jamming, a mode of digital vandalism that uses the aesthetic capabilities of the glitch to force attention to the form of the interface in which it is encountered.

The embodied experience of neurological disability is central to the formal process of Hannah Weiner's Clairvoyant Journal. As such, the work offers one possible beginning to a larger genealogy of crip-glitch artifacts.15 Weiner's encounters with hallucinated language fracture the compositional space of the typewritten page, as discontinuities in spacing, typeface, and syntax mobilize a vernacular of glitch to render an experience of disability as an aesthetic object. Units of language take on a material presence as they are projected onto her surroundings, not only compositional artifice but also found artifacts. Weiner's work triangulates the respective fields of crip theory, glitch aesthetics, and poetry, illuminating the extent to which the aesthetics of mechanical failure implied by the glitch operate in tandem with the breakdown of bodily and neurological operations that exists at the center of disability studies.

Weiner was born in 1928 in Providence, Rhode Island. After attending Radcliffe College, she worked across various publishing houses before being fired from each for "being too intellectual once for associating with aliens and once for being caught not slapping her bosses [sic] face."16 She did not begin writing poetry until 1963, after receiving a scholarship at the New School and studying with Bill Berkson and Kenneth Koch. While the influence of the New York School is apparent in some of her earlier work, such as The Magritte Poems, she described herself as someone who "couldn't write New York School poetry." Despite a slight generational difference, she is more commonly read within the context of Language poetry, which emerged in the early 1970s and emphasized more disjunctive and opaque modes of writing rather than traditional poetic techniques, emphasizing the reader's role in constructing meaning.17 Language writing offers a more appropriate model for a proto-crip-glitch poetics with tools such as paratactic syntax, unorthodox printing techniques, collage, chance operations, and textual appropriation replacing the more traditional inclinations of its New York School predecessors.

Weiner's relationship to disability studies has, until recently, been somewhat controversial. Weiner never explicitly identified as disabled throughout her life and career. Her diagnosis of schizophrenia was not public knowledge until after her death in 1997, and was first disclosed by Charles Bernstein in a tribute to Weiner in the Poetry Project newsletter in 1997.18 "Hannah's illness was often shrugged off as eccentricity, as in we're all a little crazy after all," Bernstein notes. "But few of us suffer from our craziness in the way Hannah did and her schizophrenia was not merely metaphoric, despite the fact that Hannah did not accept any characterization of herself as mentally ill."19

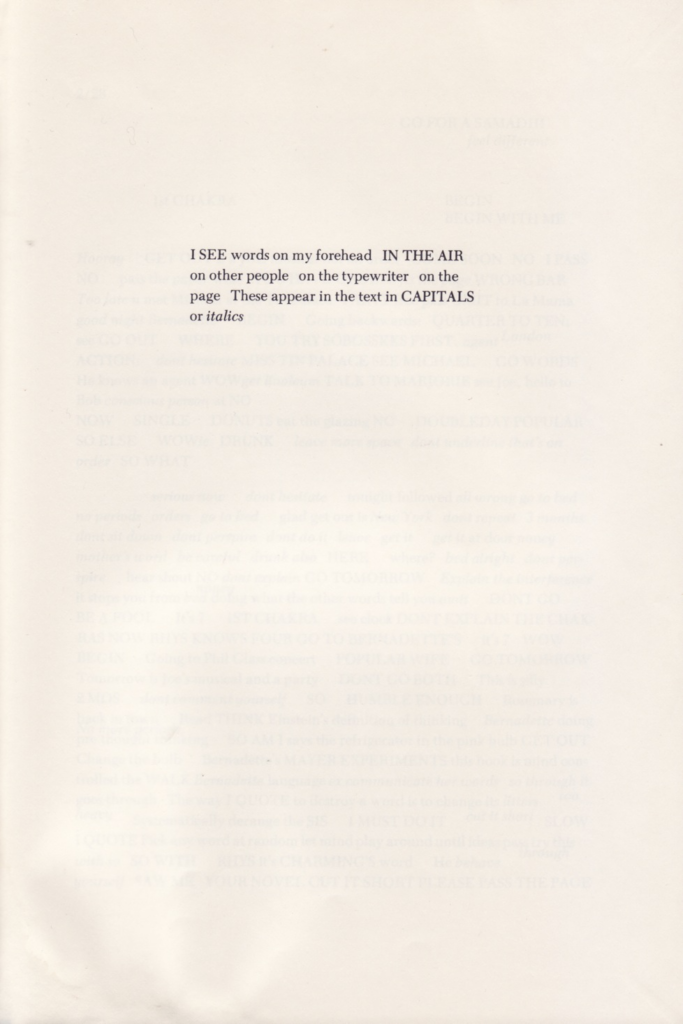

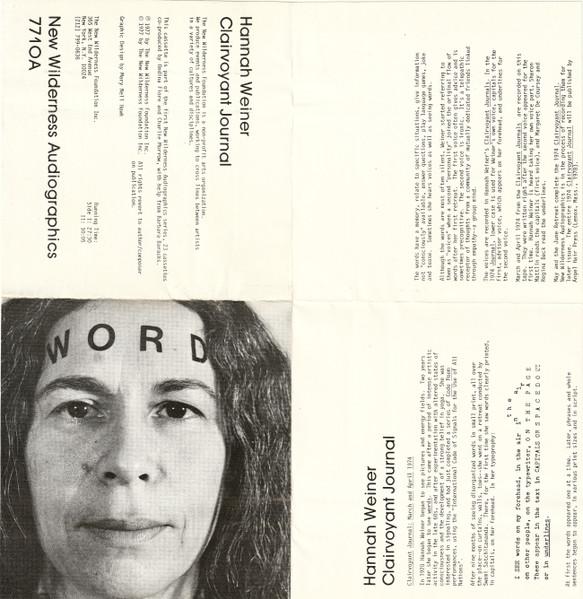

Significantly, Weiner's work far predates the "watershed moment," termed by disability scholar Michael Northen, in disability poetry following the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1992.20 In this manner, Weiner's work is adjacent to that of Larry Eigner, Josephine Miles, and Vassar Miller, who produced much of their writing over the same period and similarly kept details about their respective disabilities oblique and indirect in their poetry.21 Weiner began encountering discrete pieces of hallucinated language in August 1972, triggered by her experiments with LSD.22 It is undeniable that the clairvoyant "symptoms" of Weiner's schizophrenia existed at the center of her compositional process. "I SEE words on my forehead IN THE AIR on other people on the typewriter on the page," Weiner states in her introductory note to Clairvoyant Journal. "These appear in the text in CAPITALS or italics," she continues. 23 Her work generally relies on the transcription and representation of these units of language as poetic text, borrowing from the formal innovations of Concrete poetry and the mechanical restrictions imposed by her electric typewriter.24

Since her passing, scholars have struggled with how to categorize Weiner's relationship to her disability. Judith Goldman rightly notes that Weiner's use of the term "clairvoyance," rather than a diagnosis, pointedly "alerts us to the peculiar status of her texts without allowing us to medicalize and dismiss them."25 Patrick Durgin, who elsewhere writes on Weiner's relationship to the trope of the "proverbial mad genius of letters," argues that Weiner's clairvoyance operates as "an impairment as much as a mode of access . . . Weiner understood clairvoyance as much an impairing disadvantage as a skill to be mastered."26 Declan Gould continues after Durgin by reading "disability as poetic constraint," with particular attention to how that "constraint" is routed through the limited affordances of her electric typewriter.27 Taken together, Durgin, Goldman, and Gould not only convincingly situate Weiner as an important figure within a genealogy of contemporary experimental poetry, but as a potential crip theorist, a writer whose compositional process and application of transgressive formal structures raise essential questions regarding the capacity of the page to represent an acute experience of disability. To situate Weiner also as an early theorist of glitch is suggestively anachronistic, one that both offers an origin point to crip-glitch poetics and opens new readings of her work's investment in failure, interruption, and error.

Poetry, while not the only discipline in which the above theoretical concerns might be investigated, offers a useful basis for modeling the vexatious relationship between glitch and disability largely in its emphasis on the fragment: moments of break or slippage within an otherwise coherent literary object, which are then rehabilitated as that object's primary loci of meaning. When we first encounter a difficult poem, we often fail to grasp its meaning. Poems, like both disabilities and glitches, are quite commonly staunchly inconvenient. The page is not immediately comprehensible, but a site of difficulty and struggle. Contrary to the cultural mythos around the amputee or visually impaired climber summitting Everest and "overcoming" their disability, our focus with a page of poetry should not be on overcoming interpretive difficulty or demonstrating a false mastery over a poem's lexical meaning. Rather, a crip reading of a poem demands sitting with its difficulty, allowing it to open new avenues of meaning and interpretation on its own terms.

Jim Ferris usefully defines crip poetry, more specifically, as poetry that "centers the experience of disabled people; it shows disabled people taking control of the gaze and articulating the terms under which we are viewed."28 According to Ferris, crip poetry holds the revolutionary potential to instigate "a transformation in consciousness, not only the consciousness of the poet and the reader, but the potential to transform the world."29 Ferris makes no mention of psychiatric disability as he outlines the material and formal demands of crip poetry, yet Weiner's work still operates within the rhetorical lineage of crip poetry and poetics established by Ferris. Neurological disability, as we know, is at its core an embodied experience, despite the Cartesian separation of physical and mental experientiality that still defines both popular and medical discourse around disability. The brain is an organ prone to malfunction just as any other, and non-normative neurological conditions require the same inclusion and consideration within crip epistemologies as disabilities that are regarded as physical in nature.

The crip poetics of the glitch becomes evident as the phantasmic glitching of our neurological systems requires a staunch refusal of conventional approaches to line or meter, the defacement of page or screen a necessary analog to the disabled body or mind. Crip poetics demands an acceptance of bodily, neurological, and textual opacity. It revels in the fractured line of text and insubordinate digital interface. The reading of bodies and minds is not dissimilar to the reading of texts. We regularly demand legibility, attempt to sort both into discrete categories: poetry or prose, disabled or not. Crip poetics is hybrid, non-lexical, and resolutely fugitive. It is, in other words, a simultaneous textual and embodied glitch.

As my neurological system slowly stabilized during my glitch period, I often thought of the traumatic events that triggered it as adjacent to a piece of malware. Not every device is equally susceptible. My therapist explained this to me using an example of World War II veterans who experienced the same traumatic events: some might remain fully unfazed, remarkably untouched by the experience, whereas others would experience the same trauma-induced cognitive glitching that I was, at the time, fully embroiled within. As my symptoms became more manageable and I could read again, I came back to Clairvoyant Journal repeatedly. What do we gain by aligning the fallibility of the computer interface with our own divergent cognitive and physical processes for interfacing with image, text, or sound? What points of resonance occur between the broken machine and the "impaired" mind or body? More basically, how does the epistemology of ability presented by disability theory itself falter, spasm, or decay when brought into conversation with glitch?

Glitching Disability Discourse

How we might "glitch" our notion of ability radically changes depending on whether we position glitch as a verb or as a noun. To "glitch" ability is, first and foremost, to interrupt the current discourse of who we define as "able" or "disabled." Disability studies historically neglected (or, in some cases, directly refused) to include cognitive impairments as an object of study until the 2010s, coincidentally when Glitch Art practice was at its peak. Alison Kafer, in Feminist, Queer, Crip, was one of the first scholars to intervene in crip theory's lopsided emphasis on "embodied" forms of disability in her more general espousal of coalition between queer studies and disability studies. Kafer argues for a fluid expansiveness in the term "crip," arguing that if "disability studies is going to take seriously the criticism we have focused on physical disabilities to the exclusion of all else, then we need to experiment with different ways of talking about and conceptualizing our projects."30 To "glitch" ability is to short-circuit the current cultural discourse of what constitutes a visible "able" or "disabled" experience, to mark a fundamental failure in a discipline's attempt to catalog identity.31

Should we position "glitch" as a noun rather than a verb, the phrase "glitch ability" becomes, effectively, a tautology. A glitch is a momentary failure in ability. The normative computer and the normative body are similarly predicated on a cultural definition of presumptions of inconvenience. An important distinction in popular definitions of glitch is that it is not simply a catch-all term for mechanical failure, but rather a moment of brief yet drastic interruption in the smooth functioning of an interface. Hugh Manon and Daniel Temkin clarify the interruptive force of the glitch as "a given program's failure to fully fail upon encountering bad data . . . The garish appearance and obstreperous sound of glitch art betoken its origination in this way: a tiny variance has triggered major damage."32 The "tiny variance" of the glitch belies the more insidious language that largely led to the creation of disability as a social category. The construction of disability is inextricably tied to the invention of statistics in the nineteenth century, as the use of mathematical theories of "variance" and deviation from a supposed "norm" by Adolphe Quetelet and Francis Galton similarly underlined theories of eugenics.33 The crip subject and the glitch each come to signify algorithmic interruptions, deviations from the cleanly graphed lines and tidy sums meant to generalize body, mind, and machine as normative or not. Outside the flattening logic of statical norms, each come to signify both moments of vulgar spectacle and social disruption.

It is worth noting that while minoritarian readings of the glitch are a relatively recent turn within glitch studies as a discipline, the very beginning of Glitch Art as an aesthetic practice lies within the domain of minoritarian aesthetics and, to an extent, the attempt to visually represent a non-normative cognitive state. The iconic video art piece Digital TV Dinner, created in 1979 by Jamie Fenton (only a year after the initial publication of Clairvoyant Journal), is marked by Michael Betancourt as "one of the first, if not the very first glitch video," and arguably spurred on an entire generation of digital glitch artists.34 Digital TV Dinner was created by pounding a $300 Bally Arcade console so the cartridge pops out while the device attempts to write the game's opening menu.

As Whitney (Whit) Pow writes on the failure to access console memory in Digital TV Dinner as a representation of trans media historiography, or a record of "that which cannot be saved," we might similarly contend with Jamie Fenton's desire to create a machine that replicates the affective experience of conscious hallucination. In an interview, Fenton describes the genesis of the project: while tripping on a drug called ALD-52, which she describes as similar to LSD, Fenton attempted to replicate an alternative mental state following the realization that "the machine was 'tripping' just like I was." 35

While Fenton's altered mental state was, of course, by no means a disability, Digital TV Dinner and Clairvoyant Journal ask essentially the same question: how do we occupy and visually represent non-normative modes of thinking, feeling, and perceiving the world around us? Both rely heavily on misused, or effectively "disabled," machinery. As Fenton pounds the Bally Arcade with her fists, Weiner finagles the typewriter to fill the page with unbalanced diagonals, overlapping lines, and misaligned spacing.

The examples of art that deploy an aesthetic practice either adjacent (or formally adherent to) a glitch logic for the sake of replicating non-normative cognitive states are, in fact, numerous. Such examples include entire subcultures of digital optical art, the stroboscopic flickering of Brion Gysin and William S. Burrough's Dreamachine, the psychoacoustic sound hallucinations of Maryanne Amacher, and more.36 So, what if we read Digital TV Dinner, a universally acknowledged origin point for glitch media, as not only a figure for trans historiography but also the fugitive history of non-normative cognition, tripping, and hallucination that remains unaccounted for within glitch aesthetics? And, more basically, what if we take seriously moments of technical failure as indebted to a long genealogy of crip theory?

Cognitive Interruption & Inconvenience

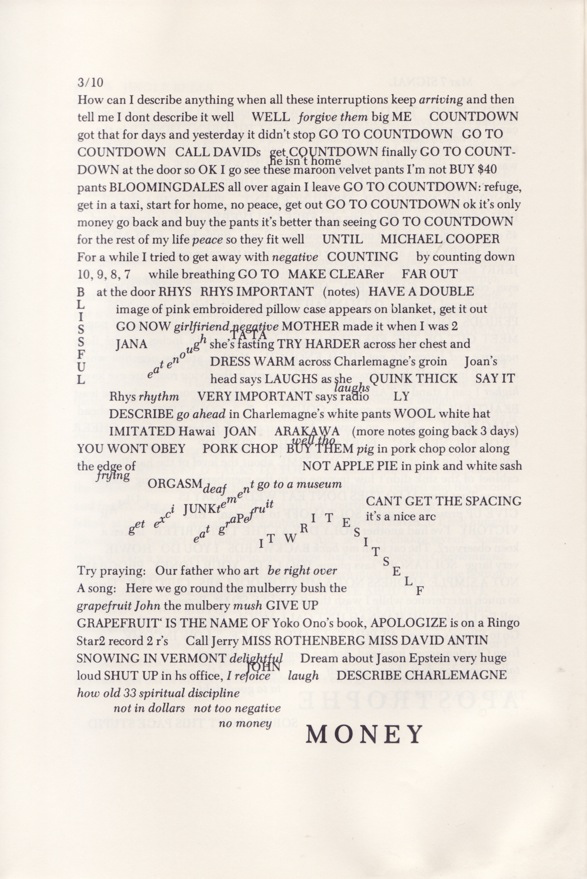

To be interrupted is an inevitable feature of holding a minor identity. To talk over another is, consciously or not, a display of power, a signal that one voice has more "right" to a sonic space than another. The unapologetically interruptive syntax that defines Clairvoyant Journal is also where we most obviously encounter a feminist and crip politic within Weiner's text. It is also, quite simply, disorienting. The various typefaces swarm the compositional space of the page, each marking the spatial coordinates of the language Weiner hallucinates onto her environment. The syntactical unit of the sentence rarely remains uninterrupted, as projected phrases resist our attempts to locate a discrete train of thought or sequence of events. While as readers we strain to find coherence within the text of Clairvoyant Journal, we are asked to inhabit a state of cognitive discomfort and confusion that replicates a crip mind.

Weiner herself claims that disjunctive, non-linear writing is necessary when representing an individual consciousness, and that the contours of our respective minds only become accessible through the formal affordances of interruption on the page. In her poem-essay "Mostly About the Sentence," which serves as an informal ars poetica for her clairvoyant work, she states:

Many things happen at once, peculiar to a journal form, to force interruptions. My writing above and below the line incorporates some of this simultaneity. Linear writing must leave out many simultaneous thoughts and events. I am trying to show the mind.37

It is necessary to clarify that Weiner's declared project of "trying to show the mind" is not, on its surface, about crip politics. When any of us process thoughts or memories, they rarely come as cohesive units of information. Our minds wander, dart, and flit from place to place, often imperceptibly, offering "simultaneous" fragments that our cognitive interfaces render into a discrete image or thought. The digital glitch similarly beckons to us with the tangled webs of data that underlie the interface, the suggestive blocks of neon following a crashed computer screen offering a glimpse behind the calculated polish of an operating system as order attempts to reassert itself. Data is rendered messy and unpredictable. It is, perhaps, a much more appropriate figure for all cognition. Before writing a sentence, we might sprint between thoughts — oscillating between topics, choosing between this adjective or that — yet the conceit of the sentence, as we read it, allows only for the often-seamless construction finally committed to the page. Weiner's work demonstrates a necessary fragmentation to all cognition, as a moment of slippage in mind or machine offers essential insight into its inner workings.

Still, Weiner's work distinguishes between what we might consider a glitched, crip consciousness — or what she terms "clairvoyant" — and that of the "ordinary" mind. In her poem "Meaning Bus Halifax to Queensbury," Weiner reinforces the didactic goal of her poetry that she first suggested in "Mostly About the Sentence": "bus Queensbury to Bradford The point is to show the mind."38 "Meaning Bus Halifax to Queensbury" is essential for locating the fugitive crip politic of her work primarily in poetic form. Two voices govern the poem. The "ordinary consciousness" is marked by Weiner as that which uses more normal syntax, a general adherence to grammar and linguistic coherence. These moments are overwhelmed by what Weiner terms a "clairvoyant consciousness," which generally follows the instructions of the language hallucinated onto her environment and attempts to "train Bradford to Leeds destroy meaning, disrupt syntax and STOP TH SENTENC."39 Here, Weiner draws a connection between the necessarily "disruptive" formal apparatus of her work and the crip consciousness of clairvoyance, one that is similarly disrupted and glitched by unbidden hallucinations of image, voice, and language.

The structure of the poem is essential to its articulation of a poetics of glitched cognition. Weiner essentially writes an essay on her poetic process that is continually interrupted by bus and train schedules. "Disjunctive, non-sequential, non-referential writing can alter bus Leeds to Branhope consciousness bus Queensbury to Haworth," Weiner writes, "allowing what is the equivalent of my seen words train Haworth to Keighley to enter ordinary consciousness."40 The "disjunctive, nonsequential, non-referential" elements of Weiner's work are enacted by the interruptions (or perhaps glitches) that punctuate that very statement, marking her formal methodology as a technique for momentarily inhabiting a crip consciousness.

At its core, the poem hinges on the colloquialism of losing one's "train of thought," which Weiner literalizes as train and bus schedules derail an otherwise cohesive explication of process. The phrase, which originates in Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan, uses "train" in the sense of a succession or sequence rather than a locomotive vehicle, or, as Hobbes suggests, a "succession of one Thought to another."41 While losing one's train of thought is not itself an experience of disability, it is an experience exacerbated by Weiner's condition. Weiner herself repeatedly gestures toward the words encountered in her spatial environment as "interruptions," which leave her with "scarcely chance to complete the phrase or sentence."42 Weiner's acute cognitive glitching is, to an extent, a mode of ability that enables her to demonstrate the minor malfunctions and errors implicit in all cognition by granting the reader access to her own.

Clairvoyant Journal, which has become arguably the most widely read and circulated work within Weiner's prolific output, was actually preceded by four "early journals": The Fast, written in 1970; Country Girl, written in 1971; Pictures and Early Words, written in 1972; and Big Words, written in 1973.43 These four texts track the steady shift in both Weiner's symptoms and their manifestation as what she later terms "large-sheet poetry," illustrating the "development of clairvoyance from feeling and seeing auras, to seeing pictures and finally to the slow development of seeing words which appeared first singly, then later in short phrases."44 As a document of Weiner's encounters with hallucinated text between January and June of 1974, Clairvoyant Journal attempts to transcribe three discrete voices, visualized "on other people, forehead included, and on every other imaginable surface or non-surface; the wall, the typewriter, the paper I was typing on, people's clothes, the air, and even words strung out in the air from the light pull (a favorite place), anywhere."45

As both an artifact of visual poetry and oral performance, Clairvoyant Journal is ultimately about what idiomatically might be described as "getting our wires crossed": an affective experience of misunderstanding and rerouting of information. The phrase originated with the invention of the telegraph, a shorthand for when the technical glitch of crossed wires caused a literal rerouting of voice to the incorrect recipient. As another wire-based communication system, the telephone appropriately emerges as an important figure throughout Weiner's entries in Clairvoyant Journal, most commonly included as an all-caps imperative:

"call Jackson," "CALL JERRY," "CALL DAVIDs," CALL RAYMOND," "CALL OMIT," "CALL JASPER JOHNS," "call Andy Warhol," "CALL JOANNE," "CALL PHIL," "CALL POSSIBLE PHONE WORKS," "CALL JIM NOT JASON," "CALL YOUR MOTHER," "CALL JANA 533 NOT HOME," "CALL RANDOM HOUSE."46

The intentional misprinting of text in the gutter overlapping two discrete lines models a literal crossing of wires, as we are similarly rerouted to a new line and voice as we scan from left to right. The telephone, especially within the context of the 1970s, might be read as a device that interrupts the domestic space of the home, analogous to the constant interruption of Weiner's daily life by hallucinated words and phrases.

In terms of content, Weiner's entries in Clairvoyant Journal are often remarkably mundane. On March 10, she lists a phone call with poet David Antin, a trip to Bloomingdale's, a healing group, and a trip to the supermarket. Nonetheless, the entry begins with an acknowledgment of how the interruptive nature of her disability makes narrative coherency nearly impossible. "How can I describe anything when all these interruptions keep arriving and then tell me I dont describe well," Weiner writes: "WELL forgive them big ME."47 The interruptions cited by Weiner are both logistical — her entries are riddled with phone calls, trips to the grocery store, poetry readings attended more out of obligation than genuine interest — and, more importantly, procedural. The language she hallucinates onto her surroundings repeatedly prevents the completion of a full syntactical unit. Any moment of description might, at any point, be interrupted by a new word or phrase in the air, on the page in front of her, or projected on her forehead.

Much of Clairvoyant Journal hinges on the multiple associations we might bring to her use of the word "well." To describe "well" is to use language with thoroughness, proficiency, and grammatical correctness. It is also, however, a marker of disability: to be "well" is to be fundamentally able-bodied and able-minded. Throughout Clairvoyant Journal, Weiner is obsessed with the performance of wellness. She bemoans her inability to avoid "foods with sugar in them" and "follow a doctor's diet," replacing donuts and apple pie with a strict regimen of cucumber juice, tuna, milk, aspirin, garlic cloves ("to clear sinuses"), and yoga.48 The text is not only a documentation of clairvoyant experiences but a reappropriation of the "diet journal," a mode of record keeping used to count calories and exercise that began in the mid-19th century.49 The invocation of diet culture throughout Weiner's body of work holds a necessary disability politic. Diet is commonly the first-line prescription demanded of individuals marked as physically or neurologically deviant, and, in my own experience, often at the expense of more material and necessary treatments gatekept by medical institutions.50 The diet journal similarly exists to police the bodies of women and gender-nonconforming individuals, demanding assimilation into Western standards of physical beauty. The interjections of dieting requirements within Clairvoyant Journal are pointedly intrusive rather than instructive, marking a failure to become "well" within a culture that punishes non-normative bodies and minds.

Weiner's internal monologue regarding wellness, above all, disrupts the text. In the entry above, her failure to "describe well" is immediately interrupted with an emphatic "WELL forgive them." Here, we encounter "WELL" not as a marker of general proficiency or health, but as a non-semantic utterance. The word "well" is often an empty signifier or pause within a statement, analogous to how an "um" marks a moment of collecting one's thoughts. At the beginning of a statement, it might colloquially indicate a resigned acceptance of what follows, as when an individual sighs "well, I guess so." It is also, perhaps more importantly, a gesture of frustration or indignation. It is as much Weiner's cognitive disability as her frustration at performing wellness that interrupts and glitches her capacity for descriptive language.

Similarly, the repeated "countdown" in the March 10 entry operates as a glitching of a common practice for mental wellness, as counting down from ten is sometimes utilized as a psychiatric exercise meant to stabilize compulsive patterns of thought. "For a while I tried to get away with negative COUNTING," Weiner writes, "by counting down 10, 9, 8, 7 while breathing GO TO make CLEARer."51 The act of counting regulates our breathing: it "makes CLEARer" an overactive mind. However, the interjections of "GO TO" that precede each "COUNTDOWN" operate as both textual and computational glitches. In coding, the "GO TO" command is a control flow statement that allows the computer to make an immediate jump to a new section of the program, bypassing the sequential execution of the code. The command fell out of fashion in the 1970s and 1980s due to its association with what is colloquially termed "spaghetti code," as the code it created could quickly become difficult to understand or maintain.52 The failure of "GO TO" as a computational command offers a clear analogy to Weiner's formal artifice: as "GO TO" enables the program to jump between lines of code, we often are forced to jump between lines of text. "GO TO" becomes a refusal of sequential order or linear structure. While Weiner counts down numerically to "CLEAR" her mind, she is repeatedly interrupted, or glitched, by the command itself.

Counting is also, of course, an important practice within any tradition of poetry. To count allows us to determine a poem's meter, and to classify and diagnose a text within a replicable structure that exists as part of a larger literary history. The dissonance that emerges when we consider the role of "counting" in a text like Clairvoyant Journal is that it is, for the most part, impossible to count. While self-presenting as a poem, it has no discernible metrical pattern for the reader to latch onto. Any time it begins to settle into a familiar cadence or rhythmic pattern, we are interrupted by another train of thought. When we consider both modes of "counting" within the text, the overall formal indeterminacy of the text becomes a marker of Clairvoyant Journal's staunch crip politic. While counting, we are unable to "make CLEARer" any formal rubric under which the text might be situated, as divergent genre becomes synonymous with neurodivergent affect.

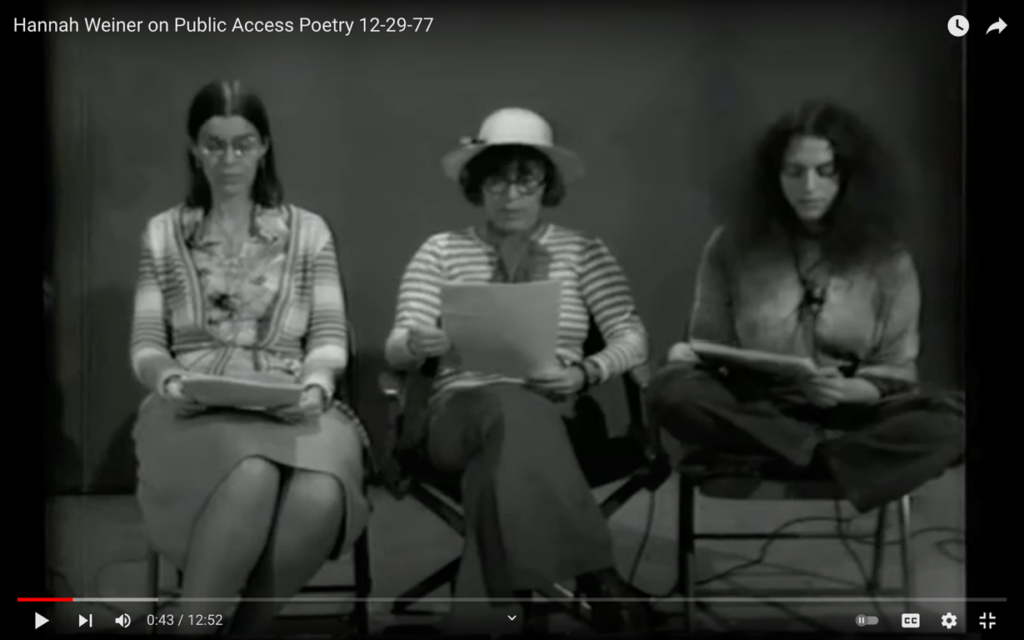

The "counting" of Clairvoyant Journal's disjunctive content requires consideration of its articulation by Weiner and her various collaborators. Despite the staunchly visual predilection of the literary artifact, Weiner conceived of Clairvoyant Journal as much a text as a script for performance. The March and April entries of Clairvoyant Journal were released and distributed on cassette by New Wilderness Audiographics in 1977, a year before the work's publication with Angel Hair. Later that year, Hannah Weiner performed the work on Public Access Poetry, a cable television program that ran from 1977-1988 featuring readings from various poets and performers. The trivocal nature of Weiner's Clairvoyant Journal recordings developed from her pre-clairvoyant work, notably The Code Poems (1982), which was similarly performed through two or three "voices" in Weiner's exploration of international codes used for communication between maritime vessels.53

The various performances of Clairvoyant Journal enact the visual disruptiveness of the text through the sonic qualities of volume, interruption, and overlapping phrases. Weiner clarifies for the audience at the beginning of the Public Access Poetry performance that "the big words are shouted by Sharon Mattlin, and the little words, which sometimes make nasty comments — I wouldn't applaud — are read by Margaret DeCoursey."54 The swift pace of the text's oration is an integral dimension of its performance, as Weiner clarifies elsewhere that the rapid-fire articulation of the various typefaces was an integral part of the group's rehearsals.55 At times, the reading takes the tenor of a heated family argument. Weiner will begin a sentence only to be rudely shouted over by Mattlin, followed by a snide interjection by DeCoursey. The sentence, and the thought, are almost always incomplete.

We might return to the articulation of the phrase from the same March 10 entry: "GO TO make CLEARer FAR OUT." The entry, which lacks italics, is read in both the New Wilderness Audiographics and Public Access Poetry recordings by Weiner and Mattlin. The articulation of "CLEARer," with the first syllable articulated by Mattlin and the second by Weiner, stands out as one moment of near-impossible translation of score into sound. In both, Mattlin delivers "CLEAR" with a sense of urgency, a characteristic shout. The two recordings deviate once we examine the second syllable. In the cassette release, the "er" is short and clipped. It remains a brief interjection, a quick amendment of Mattlin's demand for clarity. To fully "make CLEAR" remains an impossible task. The most we can do is make the poem, and the overactive mind, somewhat "CLEARer."

Weiner's articulation of the "er" is remarkably different in her Public Access Poetry performance. Here, it is expressed as a sigh or a groan, less "er" and a low and protracted urrrgh followed by a sharp exhalation of breath. It is not an amendment to Mattlin's demand for clarity but a sigh of exhaustion. The exhausted sigh is, perhaps, the most appropriate non-semantic utterance for the crip poem. It is a frustrated response to the demand for clarity from the able-minded subject and a signal of the necessary fatigue of an overactive mind. It marks the physical and mental demands of the performance itself, which moves uninterrupted at a virtuosic pace.

It is, also, itself an error. We can infer that error both from how the discrete "er" is decidedly mispronounced as a groan and from the semantic unit of "er" itself. The imperative to "make CLEARer" has, in fact, the opposite effect of what it announces. Weiner's performance wanders away from the notated utterance in the same manner that Clairvoyant Journal more generally prioritizes "wandering" and acutely non-linear thought. As Weiner "errs" in the phrase's articulation, she marks not only her exhaustion at the demand of an "exhaustive" reading of the text, but also the generative capacity of the error more generally.

In Staring: How We Look, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson observes that when "bodies begin to malfunction or look unexpected, we become aware of them."56 Her use of "malfunction," a term more regularly encountered in the context of digital technology or industrial machinery than the body, is telling. Both the malfunctioning body and the malfunctioning interface demand awareness of the formally transparent system in which they are situated. Just as we only attend to the fundamental oddity of having a body (and, of course, a mind) when we encounter its abject failure, we are similarly unable to make ourselves aware of a technological system until we experience its crash. Weiner's typewriter, for example, might remain a transparent interface through which she writes memoirs, journals, and poems until a key is stuck and the system is no longer frictionless. Disability aesthetics, with its longstanding emphasis on artifacts of failure and malfunction, becomes a means of investigating our relationship to technology more generally. The computer desktop remains an invisible container of information until its content is reconstituted by the often frenetic and hallucinatory experience of its glitching. No longer an object of glistening chrome and glass, we are forced to contend with objects of technology not as simple conduits for content but as manufactured objects with their own internal biases, prone to malfunction or accident in the same manner as our bodies.

Garland-Thomson's incisive study of the visual regimes of disability (or, as her subtitle suggestively declares, "How We Look") offers a useful addendum to Weiner's hallucinatory poetic practice. At the center of Garland-Thomson's study is the suggestion that staring exists as "a social act that stigmatizes by designating people whose bodies or behaviors cannot be readily absorbed into the visual status quo."57 We might make a similar argument regarding the frenetic typographic play within Clairvoyant Journal. Fragments of language refuse absorption into the larger syntactical unit of the sentence, as discrete phrases trail across the page or are broken by italicized or capitalized interjections. Words swim up and down the page, resistant to the same normative gaze directed toward those with commonly marginalized bodies or behaviors.

When our minds "malfunction," we become aware of the artifice implicit in our own perceptual apparatus. Weiner's preferred terminology of "clairvoyant" originates from French clair "clear" and voyant "seeing." In this context, "clairvoyance" might at first seem an inapt term for Weiner's hallucinatory poetics. Hallucination is, by definition, generally construed as a visual or auditory encounter with something that is not actually present. Both neurological and computational glitches are similarly marked as moments of frustration and opacity, an obscuration of the interface we are attempting to access. Clairvoyant Journal demands that we acknowledge the generative capacities of the glitch, attend to textual and digital fragments with the same care and reverence as we might approach an ancient Delphic oracle. To glitch ability is to acknowledge the essential coalition between mechanical and embodied forms of failure, and to reconstrue a faltering system as a possible moment of meaning-making or inquiry.

* * *

It is rarely noted that the literary form of the autobiography, or journal, was invented by a "madwoman." The Book of Margery Kempe is a dictated account of the visions experienced by Margery Kempe, who various medical historians have determined began experiencing symptoms of psychosis following the birth of her first child.58 Dictated to a scribe in the early 1430s, the text details the many visual and auditory visions experienced by Kempe throughout her various pilgrimages. Margery Kempe is candid regarding the "disese" of her "illusyons and deceytys," which she, in a rhetorical move analogous to Weiner's, reclaims as revelations from God as a Christian mystic.59

As my nervous system steadied, a therapist asked me to keep a journal documenting recursive or negative thoughts linked to my trauma event as part of our CBT regimen. Each day, I would sit at my desk and frantically scrawl disjointed notes into a cheap, spiral-bound notebook. The notes were repetitive, incoherent, and half-legible. I would tear a page out as soon as I finished writing, and then move on to the next. I never read what I wrote. I thought of Weiner hunched in front of her typewriter often. By writing out unbidden or compulsive thoughts, my therapist told me, we create distance. When we see the words, she said, the thoughts become less real.

Clairvoyant Journal illustrates within the domain of poetry a latent crip politic within all artifacts of glitch. The glitch is commonly construed as a moment of failure or irregularity, a moment in which an object ceases to work the way it should. The glitch is both metaphor and materialization of disability as a social category, the moment bodies or minds refuse to function at the standard demanded by industrial capitalism. Weiner's work rewrites the embodied and mechanical glitch as a mode of ability, one that lays bare the essential artifice of page and screen, body and mind. The alleged failure of an interface becomes an inquiry into the condition of language and perception, illuminating the fugitive underbelly of a system previously presumed to be frictionless. The glitch is not a failure of an interface but rather an afterimage of its inner workings, that which is retained when all other stimuli have ceased.

Zackary Kiebach is a PhD student at UCLA. Their research primarily focuses on the relationship between crip theory and new media.

Banner image by Dan Cristian Pădureț on Unsplash

References

- Curt Cloninger, "GltchLnguistx: The Machine in the Ghost / Static Trapped in Mouths," in GLI.TC/H READER[ROR] 20111, eds. Nick Briz, Evan Meaney, Rosa Menkman, William Robertson, Jon Satrom, Jessica Westbrook(Unsorted Books, 2011). [⤒]

- The term "crip" operates as a reclamation of the slur "cripple" by disability activists and academics. The term is often encountered within the context of crip theory, developed primarily in the academic work of Robert McRuer, Carrie Sandahl, and Alison Kafer. Carrie Sandahl describes the word "crip" as "fluid and ever-changing," much as the label of "queer," which originally targeted gay and lesbian communities, has broadened to include other minoritarian experiences of gender and sexuality. McRuer draws a similar allegiance to queer theory in his articulation of "compulsory able-bodiedness," which itself produces the experience of disability in the same way that compulsory heterosexuality produces an experience of queerness. It is worth noting that while the term "crip" originally referred primarily to experiences of physical disability, disability theorists have argued for the inclusion of cognitive disability within its reach. Carrie Sandahl, "Queering the Crip or Cripping the Queer?: Intersections of Queer and Crip Identities in Solo Autobiographical Performance," GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 9.1 (2003), 27. Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (New York and London: New York University Press, 2006), 2. [⤒]

- Rosa Menkman, The Glitch Moment(um) (Amsterdam: Institute of Network Cultures, 2011), 8. [⤒]

- Kanye West, "Welcome to Heartbreak ft. Kid Cudi," June 16, 2009. Directed by Nabil Elderkin. [⤒]

- Paul B. Davis, "Define Your Terms (or Kanye West Fucked Up My Show)" (London: Seventeen Gallery, 2009). Accessed through Seventeen Gallery. [⤒]

- Rosa Menkman, "A Vernacular of File Formats" (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 2009). [⤒]

- The first example of the "glitch" dance comes from Vanessa Clark, whose TikTok handle is @glitchgirlmaster. The video was published on June 19, 2021. [⤒]

- Kim Cascone, "Errormancy: Glitch as Divination," NOO ART: The Journal of Objectless Art (2011). In a B.A. dissertation referenced heavily by Rosa Menkman and Curt Cloninger, Iman Moradi helpfully differentiates between two modes of glitch: the "pure glitch" (an "unpremeditated digital artefact" of malfunction or error) and the "glitch alike" (the curated glitch, described by Moradi as respectively "deliberate," "planned," "designed," and "artificial"). Iman Moradi, "Glitch Aesthetics" (B.A. diss., The University of Huddersfield, 2004), 9-11. [⤒]

- For further reading, see Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (London: Verso, 2020); Meredith Broussard More than a Glitch: Confronting Race, Gender, and Ability Bias in Tech (Cambridge and London: MIT Press, 2023); Laila Shereen Sakr, Arabic Glitch: Technoculture, Data Bodies, and Archives (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2023); Whitney (Whit) Pow, "A Trans Historiography of Glitches and Errors," Feminist Media Histories 7.1 (2021): 197-230; Whitney (Whit) Pow, "Glitch, Body, Anti-Body," Outland: An Online Magazine for the NFT Era (2023). [⤒]

- Legacy Russell, "Glitch is Error," in Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (London: Verso, 2020), 74. [⤒]

- See Jon Cates "POST GLITCH," NOO ART: The Journal of Objectless Art (2014). [⤒]

- Tobin Siebers, "Disability and Art Vandalism," in Disability Aesthetics, ed. Tobin Siebers (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 3. For other recent works on disability and aesthetics, see also Alison Kafer's Feminist, Queer, Crip (2013), David T. Mitchell and Sharon L. Snyder's The Biopolitics of Disability: Neoliberalism, Ablenationalism, and Peripheral Embodiment (2015), Robert McRuer's Crip Times: Disability, Globalization, and Resistance (2018), and David T. Mitchell, Susan Antebi, and Sharon L. Snyder's The Matter of Disability: Materiality, Biopolitics, Crip Affect (2019). [⤒]

- Tobin Siebers, Disability Aesthetics, 91. [⤒]

- Siebers, 92. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, Clairvoyant Journal, 1974: March-June Retreat (New York: Angel Hair Books, 1978). Since Clairvoyant Journal does not use page numbers, I will refer to the entry date when citing specific entries. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, "Silent Teacher" in silent teachers remembered sequel (New York: Tender Buttons Press, 1994). Accessed through Electronic Poetry Center. [⤒]

- Interview by Charles Bernstein, "Charles Bernstein & Hannah Weiner: Interview for LINEbreak," LINEbreak (1995), 143. [⤒]

- Charles Bernstein, "Hannah Weiner," Jacket2 (2000). Originally published in the Poetry Project newsletter in 1997. [⤒]

- Bernstein, "Hannah Weiner." [⤒]

- Michael Northen, "A Short History of Disability Poetry," in Beauty is a Verb: The New Poetry of Disability, eds. Sheila Black, Jennifer Bartlett, and Michael Northen(El Paso: Cinco Puntos Press, 2011), 19. [⤒]

- In "Disability Aesthetics and Poetic Practice," Declan Gould is the first to note a direct lineage between Weiner, Eigner, Miles, and Miller and more contemporary poets with disabilities, notably Jennifer Bartlett and Jillian Weise. Declan Gould, "Disability Aesthetics and Poetic Practice," in The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First-Century American Poetry, ed. Timothy Yu (Cambridge University Press, 2021), 106. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, "Mostly About the Sentence," in Hannah Weiner's Open House (Kenning Editions, 2007), 122. Originally published in Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" 7(1986). [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, Clairvoyant Journal. [⤒]

- For more on the relationship between Weiner's psychiatric disability and her typewriter-based writing practice, see Declan Gould, "'45 DEGREE ANGLE CAN'T DO IT ON THE TYPEWRITER': Psychiatric Disability and Hannah Weiner's Typewriter Poetics," Amodern 10 (2020). [⤒]

- Judith Goldman, "Hannah=hannaH: Politics, Ethics, and Clairvoyance in the Work of Hannah Weiner, differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 12, no. 2 (September 2001): 122. [⤒]

- Patrick Durgin, "Psychosocial Disability and Post-Ableist Poetics: The "Case" of Hannah Weiner's Clairvoyant Journals," Contemporary Women's Writing 2, no. 2 (December 2008): 132; Patrick Durgin, "Hannah Weiner's Transversal Poetics: Collaboration, Disability, and Clairvoyance," in The Matter of Disability: Materiality, Biopolitics, Crip Affect, eds. David T. Mitchell, Susan Antebi, Sharon L. Snyder (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2019), 91, 100. [⤒]

- Declan Gould, "'45 DEGREE ANGLE CAN'T DO IT ON THE TYPEWRITER': Psychiatric Disability and Hannah Weiner's Typewriter Poetics." [⤒]

- Jim Ferris, "Crip Poetry, or How I Learned to Love the Limp," Wordgathering: A Journal of Disability Poetry 1, no. 2 (June 2007). Travis Chi Wing Lau has more recently embellished upon Jim Ferris' original definition of crip poetry in two important essays: "Toward Our Crip Poetics," an explicit response to Ferris published in Wordgathering (2018), and "The Crip Poetics of Pain," an autoethnographic essay published in Amodern (2020). In the former, Lau suggests that crip poetics requires a more intersectional approach to vectors of disabled identity. We are "messy, shifting assemblages of these things," and disability consciousness operates "in and from these interstices." Crip poetics becomes a mode of crip solidarity and enables the imaging of, in the latter, "shared, pained futures." [⤒]

- Ferris, "Crip Poetry." [⤒]

- Alison Kafer, Feminist, Queer, Crip (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2013), 16. [⤒]

- Kafer's provocation becomes the basis for Benjamin Fraser's monograph Cognitive Disability Aesthetics (2015) two years later, which tracks the theoretical, historical, and cultural representations of psychiatric and intellectual disabilities. Fraser ultimately suggests that "much attention has been placed on the need to correct a normative and able-bodied gaze, and not enough has been given to its complementarily normative and 'cognitively abled' gaze." Individuals with cognitive disabilities are labeled interruptive within public space just as much as those with more acutely "embodied" disabilities, particularly when that disability causes them to act in a manner that goes against normative social behavior. Benjamin Fraser, "On the (In)Visibility of Cognitive Difference," in Cognitive Disability Aesthetics: Visual Culture, Disability Representations, and the (In)visibility of Cognitive Difference, ed. Benjamin Fraser(Toronto, Buffalo, and London: University of Toronto Press, 2015), 10. [⤒]

- Hugh S. Manon and Daniel Temkin, "Notes on Glitch," World Picture 6 (2011). Italics in original. [⤒]

- See Lennard Davis's analysis of eugenics and disability studies in his chapter "Enforcing Normalcy" in Enforcing Normalcy: Disability, Deafness, and the Body,e.d. Lennard J. Davis (London: Verso, 1995), 23-49. [⤒]

- Michael Betancourt, Glitch Art in Theory and Practice: Critical Failures and Post-Digital Aesthetics (New York: Routledge, 2016), 23. Italics in original. [⤒]

- Betancourt, Glitch Art in Theory and Practice, 30-31. [⤒]

- Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs, "Dreamachine" (Musée des Arts Décoratifs, 1961). Maryanne Amacher, "Sound Characters (Making the Third Ear)" (Tzadic Records, 1999). [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, "Mostly About the Sentence," 129. [⤒]

- The poem appears is a 1990 issue of Tyuonyi edited by Phillip Foss and Charles Bernstein, which tasked ninety-seven poets with answering a series of questions about their process and context for their work in any format of their choosing. Hannah Weiner, "Meaning Bus Halifax to Queensbury," in Patterns / Contexts / Time: A Symposium on Contemporary Poetry, eds. Phillip Foss and Charles Bernstein (Tyuonyi, 1990), 233. Italics in the original. [⤒]

- Weiner, "Meaning Bus Halifax to Queensbury," 233. [⤒]

- Weiner, "Meaning Bus Halifax to Queensbury," 233. [⤒]

- Thomas Hobbes, "Of the consequence or Trayne of Imaginations," in Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common-Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civill (Oxford: James Thorton, 1881), 12. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, "Mostly About the Sentence," 127. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, The Fast (New York: United Artists Books, 1992); Hannah Weiner, Country Girl (Berkeley: Kenning Editions, 2004). Pictures and Early Words and Big Words remain unpublished. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner and Charles Bernstein, "Excerpts from an Interview with Hannah Weiner," in The Line in Postmodern Poetry, eds. Robert Frank and Henry Sayre(Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 187; Hannah Weiner, The Fast. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, "Mostly About the Sentence," 126-127. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, Clairvoyant Journal, March 1, March 7, March 10, March 15, March 23, April 1, April 4, April 14, April 21, April 22, June 9. [⤒]

- Weiner, Clairvoyant Journal, March 10. [⤒]

- Weiner, Clairvoyant Journal, May 10, May 12. [⤒]

- The first "diet diary" was published in 1857 under the title Corpulency, i.e. Fat or Embonpoint, in Excess: Letters to the Medical Times and Gazette by A.W. Moore. The latter portion of the text included a ledger for readers to fill out, marking what they ate at various points during the day. [⤒]

- For further reading on how diet recommendations for disabled individuals are often undergirded by ableist assumptions on health, see Susan Wendell, The Rejected Body: Feminist Philosophical Reflections on Disability (New York and London: Routledge, 1996), 85-116. [⤒]

- Weiner, Clairvoyant Journal, March 10. [⤒]

- The efficacy of "GO TO" was most famously questioned in a letter to the editor by Edsger W. Dijkstra titled "Go To Statement Considered Harmful" in 1968, which argued for its complete abolition from all "higher level" programming languages. Edsger W. Dijkstra, "Letter to the Editor: Go To Statement Considered Harmful," Communications of the ACM 11, no. 3 (1968): 147-148. [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, The Code Poems: From the International Code of Signals for the Use of All Nations (Barrytown, New York: Open Book Publications, 1982). [⤒]

- Hannah Weiner, Sharon Mattlin, and Peggy De Coursey, "Appearing on Public Access Poetry," December 29, 1977. Published on PennSound, 2010.[⤒]

- Weiner, "Mostly About the Sentence," 127. [⤒]

- Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, Staring: How We Look (Oxford University Press, 2009), 37. [⤒]

- Garland-Thomson, Staring, 44. [⤒]

- See Marlys Craun, "Personal Accounts: The Story of Margery Kempe," Psychiatric Services 6, no. 56 (June 2005): 655-656. [⤒]

- Margery Kempe, The Book of Margery Kempe (Kalamazoo, Michigan: Medieval Institute Publications, 1996), 23. [⤒]