Locating Lorine Niedecker

On a brilliant August day in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin — a micropolis of 12,489, as of the last census, referred to succinctly by locals as Fort — we park across the street from an "urgent wave of verse"1 that floats between the north-facing windows of a shop selling baseball cards, its bold primary colors filling two stories of pale brick:

Fish

fowl

flood

Water lily mud

My life

Drawn from the Objectivist poet Lorine Niedecker's "Paean to Place," the serif letters emblazoned here constitute one of two murals by artist Jeremy "Guzzo" Pinc that frame both sides of North Main Street. (A third illustrates "Mergansers" from North Central on the Hometown Pharmacy downtown, and a fourth illustrates the opening lines of "Come In" — "Education, kindness / live here"2 — and its courteous canine at Luther Elementary School.)

Fig. 1. The Niedecker poetry walls by artist Guzzo Pinc that frame North Main Street in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin. (Photos: Sarah Dimick)

As we approach the nucleus of downtown along the Rock River, heading southeast from Madison on the Iron Brigade Memorial Highway, we are buoyed by this realization of the organizers' aim of centering Niedecker "in front of our community so that her words could not be missed."3 There is something profoundly moving about this hometown pride: not for a war hero, business magnate, or hockey star, but instead for a mid-twentieth-century woman poet who spent years writing alone in a 20' x 20' cabin amidst nearby Blackhawk Island's riverine quiet.

As a poet, Niedecker is — and has always been — simultaneously beloved and overlooked. We have traveled to Fort Atkinson together to comb through her archives, which are housed in the Knox Research Library of the Hoard Historical Museum — which occupies the same building on Whitewater Avenue as the National Dairy Shrine. The papers of other notable Objectivist poets are located in large research institutions. Louis Zukofsky's papers are stored at the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin, and George Oppen's papers are kept at the UC San Diego Library Special Collections, places distant from their originary contexts. But, Niedecker's letters, manuscripts, and even her writing desk are lodged here, a 4.5-mile walk from her home, among artifacts of the Black Hawk War, dioramas of Late Woodland Moundbuilders, a vast collection of taxidermied waterfowl, butter churns, and a multimedia show that captures "the sights and sounds of dairy farming: past, present, and future."

When we arrive, Merrilee Lee, the Hoard's director, greets us with the warmth of one similarly afflicted with archive fever, and she facilitates our deep dive into the collection, which reveals dimensions of Niedecker's artistic ambitions heretofore unfathomed. Merrilee's enthusiasm is echoed by the rest of the staff, who are proud to talk about Niedecker's legacy (and one of whom offers us ice cream leftover from a recent social). There is a difference between being preserved and being treasured: Zukofsky and Oppen may be the former, but Niedecker is certainly the latter.

In fact, since her death in 1970, Niedecker's poetry has sustained a society of friends and devotees here in Fort Atkinson whose loyalty may be unrivaled within American literature. On the screened porch of Cafe Carpe ("idiosyncratic since 1985") following a morning poring over Niedecker's papers, we meet Ann Engelman, a consultant for Wisconsin Public Television, and Amy Lutzke, the Assistant Director of the Dwight Foster Public Library. Ann recently handed over the presidency of the Friends of Lorine Niedecker to Amy, and both women are walking encyclopedias of Niedecker's poetry, biography, and trivia. Niedecker's favorite cocktail: the Grasshopper, made of melted vanilla ice cream tinted startlingly green with crème de menthe. Where to access a "field guide" to the three dozen bird species referenced in Niedecker's Collected Works. Details on the ongoing restoration of her cabin — now listed on the National Register of Historic Places — and the desire to have it accommodate a writer's residency. But even more, the Friends promote the enjoyment of and scholarship about Niedecker's work. They publish a semiannual newsletter called The Solitary Plover, keeping Niedecker fans abreast of archival developments and community news — the recovery of 118 books from her personal library, free birthday cake at the Hoard Museum on her 120th birthday, a visit from a French translator working on a set of Niedecker poems. They host an annual poetry festival in Fort (on hiatus since the rise of COVID), hold virtual readings, invite the citizens of Fort to "Write on the River," and co-sponsor with Write On, Door County the Lorine Niedecker Fellowship, a stipended two-week residency "to promote new work that deals with the poetry of place." Moreover, through lorineniedecker.org, the poet's resource-rich digital home, the Friends extend and facilitate Niedecker's enduring invigoration of poetic scholarship and practice around the world. All of this strikes us as remarkable, a dedication to local literary history that rarely sustains itself with this kind of vision and alacrity. And yet, the Friends worry whether it is enough: they wonder if social media could be harnessed more advantageously, routing more readers, beyond the 1,500 who currently follow their Facebook page, towards Niedecker's work.

Worries about the maintenance of Niedecker's legacy, however, might be quelled by the steady outflow of work that seeks to illuminate the complexities of Niedecker's poetry and translate it across media, disciplines, and languages. In addition to the playfully polychromatic murals of Guzzo Pinc, Niedecker installations — often arising from collaborations between local artists and school children facilitated and funded by the Friends — can be found at seven area schools, ranging from shimmering mosaics by Denny Berkery to an elegant setting of "Smile / to see the lake" floating above stained glass dragonflies and metal bulrushes crafted by Jourdyn Cluver, Caroline Graves, and Kendra Riddle. Since 2018, sculptor Sally Koehler's statue of Niedecker, Our Poetry Lady (her nickname among Fort's schoolchildren), has loomed, all seven feet of concrete and blue mosaic dress, above the cyclists coursing along the area's Glacial River Trail. Farther afield, Niedecker's Lake Superior (issued by Wave Books as a stand-alone collection with sources and critical apparatus in 2013) inspired curator Catherine Haggarty of Proto Gallery, Hoboken, to organize We Are What the Seas Have Made Us, featuring New York-based painters Yevgeniya Baras, Daniel John Gadd, Dana James, and Alan Prazniak, whose abstractions, like Niedecker's poem, "ask of us, rather than demand," Haggarty writes, "that we decide where we are on our own terms." Beyond allusion or depiction, interdisciplinary artist and concrete poet Francesca Capone manipulates the printed text of Niedecker's "Sewing a dress" in her Oblique Archive III (2014) such that it veers and stammers in columns of distorted graphemes that intermingle with those from Zukofsky's "A Valentine" — a modified version of which was featured as the cover image of the Poetry Project's Newsletter:

As the Paterian adage runs, all art aspires to the condition of music, and it is no surprise that a poet so enamored with the melodious capacities of nature and everyday speech and who, as an Objectivist, viewed the poem as a performative score, would appeal to contemporary composers. With Harrison Birtwistle's Nine Settings of Lorine Niedecker (1998-2000) and Three Settings of Lorine Niedecker (2011), Niedecker joins Sappho, Whitman, Celan, and Neruda in the acclaimed British composer's poetic pantheon. In the first series, these miniatures for soprano and cello produce, as Stuart Montgomery said of Niedecker's "Traces of Living Things," a "strange feeling of sequence"4 as they draw work from across the poet's oeuvre in achronological progression toward the "darkinfested" torments of "Sleep's Dream." Crisp articulations of lyrics such as "Hear Where Her Snow-Grave Is" — wherein the singer draws and divides the "mourn" of "mourning doves" into something like onomatopoeia — emerge from the cello's dry angularities. Even though they treat some of the same poems (such as "Always North of Him" and "My Life by Water"), this approach stands in sharp contrast to Jerry Hui's Three Poems by Lorine Niedecker (2012), composed for the Isthmus Vocal Ensemble, whose warm choral splendors actively challenge stereotypical notions of the poet's isolation, and John Harbison's Seven Poems of Lorine Niedecker (2015), for soprano and piano, which presents voice and instrument as ludic co-laborers in aural affinity, asking with spritely brio, "Why can't I be happy / in my sorrow?"

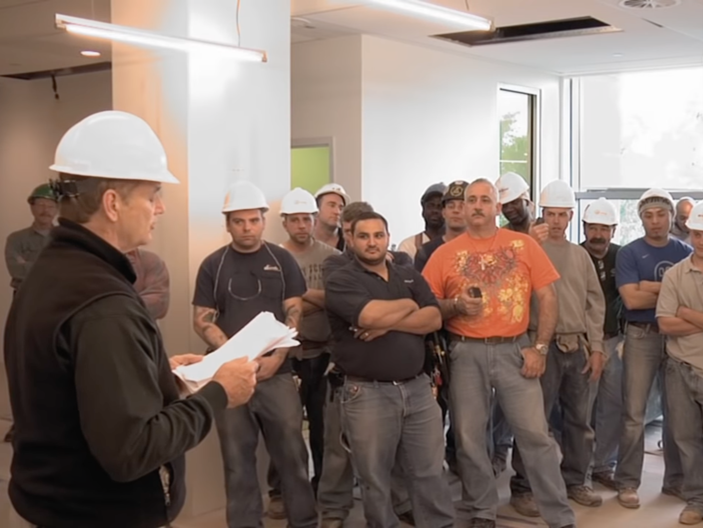

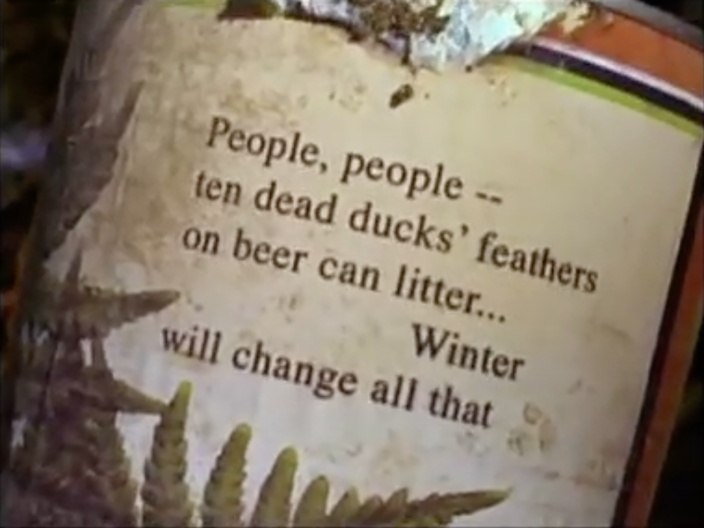

Speaking of co-laborers, in the realm of the cinematic arts, Bill Murray recited "Poet's work" — "For the shorter attention span crowd," he mock-scolds members of the construction crew who built Poet House's facility at 10 River Terrace — as part of a video segment produced in May 2009 by Limey Films called Gathering Paradise. "We're getting paid by the poem here; so, that's piecework," the comedian and self-described poetry aficionado says with a grin to the hard-hatted men, gathered in a bashful knot on their union break. This current of camaraderie, founded on the acknowledgement of overlooked work, flows through Cathy Cook's experimental documentary portrait Immortal Cupboard: In Search of Lorine Niedecker (2009, Sprocket Productions), a filmic labor of love that operates through a poetic logic of superimposition. Having been "flooded with imagery"5 after reading Niedecker's poetry, Cook translates the poet's words, locating visual correspondences through archival footage, contemporary montages of Blackhawk Island environs, and black-and-white vignettes recreating Niedecker's private world. Poetic texts are situated in their constitutive environments, as when the text of "People, people —" from the For Paul manuscript cleverly appears on the label of a tin can littering Blackhawk Island Road. Waterfowl and frogs provide the soundtrack as a disembodied voice assures us: "There are all these myths about Niedecker's isolation and misconceptions about Fort Atkinson — you know, that she was an amazing naïve poet or whatever. There is nothing naïve about her."

Fig. 4. Film stills from Cathy Cook's documentary Immortal Cupboard: In Search of Lorine Niedecker (2009, Sprocket Productions).

The sustainment of a poet's legacy is a perduring, necessarily collaborative process, the proverbial torch getting passed, if one is lucky, from the writer's immediate contemporaries — such as her first and current literary executors Cid Corman and Bob Arnold — to readers whose attachments to Niedecker stems from chance encounters with the work (her poetry still so rarely appears on syllabi, especially beyond her home state). The conversation's nurturance is not a foregone conclusion. In this regard, we are grateful to be the beneficiaries of the field-defining work of Jenny Penberthy, scholar and editor of the surviving Zukofsky correspondence (1993), the pathfinding editorial volume Lorine Niedecker: Woman and Poet (1996), and the triumphant Collected Works (2002) and its variorum wealth. Elizabeth Willis's Radical Vernacular: Lorine Niedecker and the Poetics of Place (2008) divines a guiding constellation of preeminent poet-scholars such as Eleni Sikelianos, Lisa Robertson, Rae Armantrout, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, and Anne Waldman, among many others, to illuminate many paths toward an answer to the perennial query: "Where — or how — should contemporary readers place Lorine Niedecker?"6 In the fifteen years since that collection was released, there has been a steady stream of brilliant criticism among our generation of scholars. She has also only very recently passed into French and Spanish, through the translative labors of Martin Richet — including the brand-new edition Cette condenserie (éditions corti, 2023) — and Maria Negroni. Writing in his preface to the early British tribute anthology, The Full Note: Lorine Niedecker, editor Peter Dent proclaims, "The time is surely right for her singular, unaffected and subtle voice to be heard once again — heard and sustained. There should be no further lapses."7 Perhaps as some ritual transferal of responsibility, however, Niedecker remains the type of figure — unfixable in the firmament of American poetry — whose work requires periodic resuscitation in the broader discourse, even as its charms continue to reward the faithful.

In this cluster, Hoa Nguyen — a celebrated poet in her own right — examines what ties her to Niedecker, to "being a poet and being under-employed and in a body gendered as a woman." Nguyen traces the crucial influences of global poetry on Niedecker's writing, opening to the disparate yet linked histories of Blackhawk Island, Saigon, and zones of pandemic isolation. Meanwhile, Sasha Steensen narrows in on the rock formations of the Great Lakes region, reading Niedecker's poetic compressions alongside geology. Three new environmental readings of Niedecker's life and work are offered by Samia Rahimtoola, Michelle Niemann, and Sarah Dimick. Rahimtoola takes up infrastructure — specifically, Niedecker's beloved pressure pump, installed in her cabin in 1962 — and traces the concept of homeostasis across mid-century ecology and poetics. Niemann, via astute close readings of Niedecker's New Goose, a collection submitted in 1944 and published in 1945, positions Niedecker's work at the beginning of the uptick in production, consumption, and emissions now referred to as the Great Acceleration. Dimick reflects on the years Niedecker worked as a cleaner at the Fort Atkinson Hospital, threading issues of occupational health and environmental safety through the economic precarities and ethnic divisions of the cleaning staff. And, in reading Niedecker as a queer icon, Brandon Menke theorizes what he calls "lyric drag," building to an analysis of how the poet Jonathan Williams writes poems as if Niedecker might have written them herself. In their confluences and divergences, these essays revitalize ongoing conversations about Niedecker's poetry and break new ground in critical conversations, allowing us to appreciate her anew.

In addition to these vital provocations, we thought it would be a major missed opportunity, given the collective talents of all these poet-critics, if we didn't showcase those evocations of Niedecker that have manifested in their own poetry (and ours) and those of friends and colleagues, allowing us to broaden the frame beyond those of us contributing essay. Thus, we have gathered together The Marsh portfolio — a rhizomatic efflorescence of Loriniana featuring the poetry and reflections of Hannah Brooks-Motl, Sarah Dowling, Tiff Dressen, Kelly Hoffer, Stephanie Burt, Michelle Niemann, Brandon Menke, Sasha Steensen, and Kerri Webster — which demonstrates how powerfully Niedecker speaks to our contemporary moment.

Even as stars among her contemporaries have faded into relative obscurity, Niedecker's poetry pitched resolutely between — between avant-garde experimentalism and ethnopoetics, between the gnomic and the manifest — has sustained, across the decades, stalwart devotion. Her position within the canon of twentieth-century American modernism may seem to be in flux, shifting between various contexts — Objectivism and ecopoetics, white settler colonialism, geological and geopolitical history, the artistic legacies of the New Deal and the Popular Front, midcentury feminism, Thoreauvian hermeticism transplanted to the Midwest. Her work can feel both elusive and profusive, her poetic evolution traced across fugitive volumes produced by tiny presses and now appearing in Selecteds and Collecteds rife with textual variations. In our attempts to locate Lorine Niedecker, we do not seek to pin her down but rather to let loose the frustrating delights and joyful contradictions of her art.

All pilgrimages necessitate a visit to the final place of rest. After exploring her watermarked cabin and listening as rain pockmarks the water languorously rolling past her Blackhawk Island home, we travel a narrow county road to leave nosegays of pink clover and chicory — "Open-field / blue-wheeled" — upon her grave.8 Buried, we are told, among the unchurched, Niedecker is there, having been set down into her native soil during a blizzard in January 1971, where she has always belonged. But, now 120 years after her birth, she is resolutely, in all her tenderness and grit, here among friends.

Sarah Dimick ( @sarahdimick ) is an Assistant Professor of English at Harvard University. Her research, based in Anglophone literatures of the 20th and 21st centuries, focuses on literary portrayals of climate change and environmental justice.

Brandon Menke ( Twitter: @bamenke; Instagram: @queer_lyricism ) is a poet and scholar of queer art and literature. He is assistant professor of English at the University of Notre Dame. His creative and critical work is found or forthcoming in Poetry, The Yale Review, Denver Quarterly, and the edited volume Elegy Today: Revisions, Rejections, Re-mappings.

References

- Lorine Niedecker, Collected Works, ed. Jenny Penberthy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), 265.[⤒]

- Lorine Niedecker, Collected Works, 190.[⤒]

- Amy Lutzke, "Something There Is That Loves a Wall: A Bramble Conversation with Amy Lutzke of the Friends of Lorine Niedecker," Wisconsin Fellowship of Poets 2018 https://www.wfop.org/something-there-is-that-loves-a-wall[⤒]

- Lorine Niedecker, Collected Works, 238.[⤒]

- For an interview with the director on Director's Cut, produced for PBS Wisconsin, go here.[⤒]

- Elizabeth Willis, Introduction, Radical Vernacular: Lorine Niedecker and the Poetics of Place (Iowa City: Iowa University Press, 2008), xiii.[⤒]

- Peter Dent, Preface to The Full Note: Lorine Niedecker (Devon: Interim Press, 1983), 5.[⤒]

- Lorine Niedecker, Collected Works, 206.[⤒]