Issue 1: Deindustrialization and the New Cultures of Work

No observer of contemporary American economic life can overlook the fact that real wages have remained almost unchanged for over forty years.1 Stagnant wages seemingly scandalize liberal platitudes of progress. As an economic matter, they limit consumption, and if productivity increases quickly while wages lag far behind, they can produce a crisis of overproduction. But while wages have remained largely stagnant, forms and modalities for thinking about labor have proliferated in critical theory and in literary and cultural studies. Over the last twenty years, scholars have developed an expansive terminology for describing labor: affective labor, cognitive labor, digital labor, gendered labor, feminized labor, consumer labor, intimate labor and sexual labor. Terms like "gendered labor," "feminized labor," and "care work" (and rarely "sexual labor") have largely supplanted "house work" — a change we can attribute to the movement of more women into non-domestic workplaces and to the transformation of their formerly unwaged domestic work into the waged work of other, often non-white women.2 Whereas Frankfurt-School "fellow traveler" Alfred Sohn-Rethel once argued that the crucial division under capitalism was between "intellectual and manual labor," and while Marx himself offered labor's basic division of "abstract labor" and "concrete labor," such terms are rarely used outside of political economy today.3 As manufacturing has ceded the dominant share of the U.S. occupational field to service, "manual labor" has been replaced by "service work." "Mental labor" has declined in use almost to the point of obsolescence, only to be replaced by "cognitive labor," "creative labor" and in some cases "digital labor." With the attenuation of the social welfare state, "civic work" has become "volunteer work." "Emotional labor," a 1980s term that sought to account for a feminized formal labor, now seemingly falls under the broader rubric of "affective labor." Older distinctions such as skilled vs. unskilled or productive vs. unproductive likewise seem to have little currency today. In the proliferation of various new terminologies for naming labor, we can sometimes lose sight of the stagnant wages underpinning their emergence.

I understand the proliferation of these terms as an expression of sociocultural critics' desire both to qualify how we work and to treat perceived changes in work as a means of periodization. Many of these substitutions and transformations may be traced to one of our most cited locations of contemporary economic break, namely the 1970s, as the Fordist mode of regulation and with it certain forms of Keynesian management ceded into what we now recognize as a financialized economy. With deindustrialization in the U.S. and other developed countries, industrial wage labor ceded ground to service labor, reproductive labor, and affective labor — and it did so not only in the real economy, but in critical political economy as well.

In this paper, I want to nuance this perceived relationship between changes in the way we talk about labor and changes in labor itself. Without a doubt, industrial work and wage-based Keynesianism gave way under the global economic restructuring of the 1970s. Yet instead of tautologically suggesting that a new period is defined by new labor, and that new labor inaugurates a new period, I want to understand the ways that changes in labor's organization make visible forms of labor always there but previously out of view.4 Labor's categorical stability is more robust than the many supposed modifications of it imply. For instance, instead of arguing that women's presence in formal labor feminizes work in accordance with the parameters of a service economy, I suggest that as women enter the waged workforce, an understanding of gender as labor previously invisible to classical political economy becomes newly available to theory.5 I thus want to emphasize the overlap and continuity between not only between gendered labor and emotional-affective labor but also between wage-labor and no-wage labor. In so doing, I want to resist the treatment of wages as merely metaphorical and instead insist on a return to a focus on the wage as a metric.

In seeking to account for the remarkable rise of affect as an optic for critical and political economic analysis, Patricia Clough has argued that we have undergone an "affective turn." 6 In this article, I suggest we need "an effective turn": a rethinking of the politics and metrics of the wage and its associated benefits and losses. If the affective turn sought to resuscitate affect from its largely philosophical and psychoanalytic genealogy in order to situate it prominently in the world of global value production, then the effective turn seeks to return to the problem of inflation, wages, and the relationship between shifting coordinates of value or money and labor.7 It may seem redundant to return to such questions; after all, wasn't the whole point of terms such as affective labor, emotional labor, gendered labor and so on to move away from the economism that all too often was indifferent to the social lives of workers themselves, including their race, gender, and nationality? Did not such terms seek to introduce into those categories dimensions of work and labor that could not be described through mechanisms of the wage alone?8 Of course. Yet perhaps we have over-corrected. In calling for an effective turn, I am being more provocative than programmatic, but I am also, I think, noting a certain neglect of some economic forms in what we collectively refer to as economically oriented cultural criticism.

At the same time, I do not want to suggest that wages are a straightforward metric. They are a fundamentally contradictory social form. Thus, to take one example, "wages for housework [are] at the same time wages against housework," in the compelling words of Silvia Federici.9 Indeed, the wage never measures the value of the work performed, but is merely the price at which labor power is sold, a price that doesn't correlate (at least not directly) to labor's productivity but only to the price of its reproduction. The fact of a gap between labor's value and its price is fundamental to the Marxist theory of surplus value. Yet the opposite claim — the fiction that the worker is paid what her labor is worth — is equally central to capitalist ideology, as is the fantasy that labor always benefits as much as capital does from improvements in labor's productivity. Here, I want to consider a moment when it seemed to capital as if workers were being paid too much while workers themselves felt they were being paid too little, given rising prices for everything but labor. In this same period, as Fordism and Keynesianism came to seem too inflexible and began to give way to post-Fordist manufacturing systems and anti-union campaigns, it was becoming increasingly obvious not only that capital was becoming less productive, but also that workers were no longer benefiting from the immense productivity gains made possible by the various technological revolutions accomplished during the midcentury boom. During this 1970s and early '80s period of anxiety, I argue, the separation between wages and work became visible in new ways, as a separation that happens when we work without wages (housework), when we work for increasingly inadequate wages (wage stagnation), when we earn wages for something that doesn't really seem like work (expressions of affect or instantiations of gender), when we work for money that isn't a wage (crime), when getting higher wages requires a period of getting no wages at all (strikes), when wages are demanded without work (universal basic income), when we work for a wage that isn't enough to pay for basic needs like housing and food or when we work for housing and food instead of for wages (low-wage or no-wage work).

To situate my claim about the separation — real or imagined; salutary or regressive — between work and the wage, I use as a periodizing frame a more local, limited and discrete event than what has been called "financialization." Following Jacques Derrida, literary scholars have long located a crucial transformation in economic signification in the 1973-end of the Bretton Woods Accord and its decoupling of the dollar from the gold standard.10 Such accounts have argued that by robbing money of the (appearance of) intrinsic value embedded in gold, fiat money forced a radical separation between money and value similar to the separation between signifier and signified. Here, however, I want to amend this historiography to insist on the continued importance of work for political economy even in an age of financialization. In the same 1970s era named above, the effects of systemic inflation — the explosion of commodity prices that occurred between the early 1970s and early 1980s and was later called "The Great Inflation" — made possible new articulations of labor, even as those forms of labor were not new. Inflation and inflation discourse, I am suggesting, opened a fissure or break between work and its representation or measurement by the wage, a break similar to the gap between money and value described by theorists of financialization. The effects and afterlives of 1970s inflation persisted even beyond its official extinguishment in the mid-1980s, after Paul Volcker, the Reagan-appointed Chairman of the Federal Reserve, raised the federal funds rate substantially and allowed both interest rates and the unemployment rate to skyrocket.11

As I pursue my case, I will argue that as organized labor came to appear as an inflation-driver through the discourse of excessive wages — so-called "wage-push" inflation — one effect was a conceptual separation between wage and work. Inflation was understood as a result of this break between work and wages — since wages were seen as too high. More to the point for this essay, it also made visible the separation between work and wage, and it did so in a range of sites and contexts, including those named above. We see the effects of this break throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, when it resulted in both progressive and regressive claims and critiques. The break allowed different articulations of labor to emerge that were not indexed to the wage. Emotional labor and affective labor were explored through analyses of informal domestic labor, disconnecting work from the presumption of the wage. The idea of universal basic income, first proposed by neoliberal economist Milton Friedman but since claimed by all ends of the political spectrum, severed the link between wage and work from the other direction, by guaranteeing wages without requiring employment. The inflationary 1970s and 1980s also saw a variety of labor films, from documentaries such as Finally Got the News (1970) and Who Killed Vincent Chin? (1987), to the gonzo-style Roger & Me (1989), to Hollywood romance Norma Rae (1979), to historical recreations Matewon (1987) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975), to the transnational drama El Norte (1983). In this period, we can perhaps speak of great labor films, as for the 1930s we can speak of the great labor novels.12

In particular, I argue that Sidney Lumet's feature, Dog Day Afternoon, and Barbara Kopple's documentary American Dream (1990) distinguish themselves by their symptomatic capture of certain residual and emergent modalities of labor. Lumet's film situates the emotional labor of masculinity within a moment of wage recession. Meanwhile, we might read American Dream not only as the last documentation of the Keynesian wage, but also as a text that isolates what we can now recognize as affective labor. The former film shows how the confident, masculine bank robber of crime films becomes a queer criminal who cannot get a unionized job. In the latter, the masculine affect required by industrial workers becomes visible only as it breaks down during a failed strike. By analyzing how both labor films introduce gendered logics into their genres, we can see how the gap between work and wages makes visible the gendered components of labor.

The Emotional Labor of Armed Robbery

Fig. 1. Workers' demands and inflation are presented causally linked in an illustration in "Inflation: On Prices and Wages Running Amok," (1973), reprinted in Matthew T. Huber, Lifeblood: Oil, Freedom and the Forces of Capital (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2016), 115.

In 1973, the Federal Government's Cost of Living Council released the pamphlet "Inflation: On Prices and Wages Running Amok," from which the above cartoon is taken. This pamphlet was produced via one of many government programs throughout the decade that sought to make legible both the problems of and remedies for inflation. Despite such efforts, inflation would define the decade, topping out at 13 percent a year at its height in 1979. Other programs to explore and explain inflation included president Gerald Ford's WIN (Whip Inflation Now) program, which invited subjects to don a sticker/button on their person to indicate that they, too, were committing to "WINing." As inflation began its steady rise throughout the 1970s, singers sang about it, news reported on it, citizens protested it, and one season of the popular television show All in the Family opened with an episode dramatizing it.13

Inflation was a symptom of broader economic changes that would continue to shape the coming decades, but here I treat it as a discourse, one that both cited and reproduced a sense that there had been a break between wages and work.14 We note one indication of this separation in the claim that wages are too high (or, rarely, too low). In practical effect, the claim of wages being "too high" produced a range of meanings, from the concern that certain people were being overcompensated for some work to the worry that others were receiving money for no work. We see such a concern displayed in the cartoon above: people don't work for wages; they demand wages. In such a scheme, money is not realized through labor completed over time, but has instead been given over to a certain instantaneity. Particularly in the first half of the 1970s, inflation was perceived as a general malaise, but by that decade's end, primary responsibility for it had been assigned to two groups: organized labor within the United States and Arab countries abroad.15

The representation of inflation, I want to argue, tells us something about price, about wages, and ultimately about the constitution of labor. The 1970s and early '80s are recognized not only for their inflation but also for their new formulations of labor, centrally theorizations of domestic work and emotional labor. Inflation functions as a kind of quilting point that holds together conceptual variation within labor. Who works and how they worked was changing under the sign of larger macroeconomic reorganization, and gender itself became conceived of as a kind of labor at the same time that the price for labor suffered a loss relative to other commodities. In Lumet's Dog Day Afternoon, a filmic recreation of a 1972 bank robbery in Brooklyn, the inflationary separation of work from wage becomes visible. In the wake of this separation, I contend, we see the visibility of gender as a kind of as-yet untheorized emotional labor.

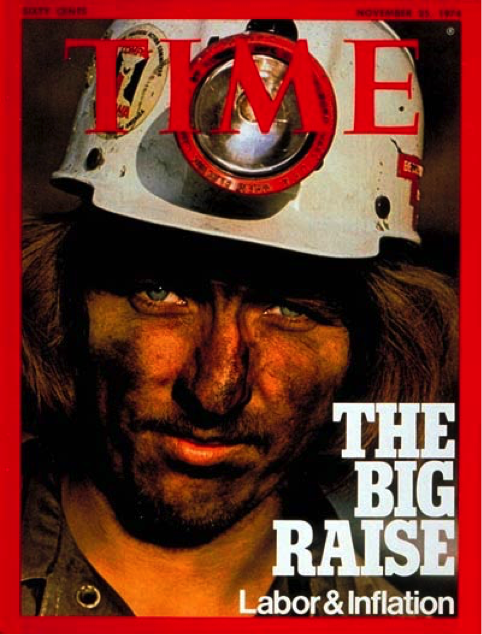

Lumet's film captures a popular economic discourse according to which organized labor was emerging as a cause of inflation: "The Big Raise: Labor and Inflation," announced a Time magazine cover in 1974; this was only one of many such popular indictments. Whatever else it was, inflation was both an anti-labor discourse and a discourse that claimed the price of money had central bearing on possibilities of social change. Indeed, Melinda Cooper has shown that American neoliberal economists and political theorists repeatedly employed what she calls "the moral discourse of inflation" to undermine myriad forms of economic equality that might have resulted from 1960s social movements.16 Dog Day Afternoon does not replicate this precise discourse, but its ambivalent imbrication within it has effects within the film, including its oft-cited generic reformulation.17

Fig. 2. The Anti-Labor Discourse of Inflation, Time Magazine, November 25, 1974

The plot of the film follows nascent bank robbers Sonny (Al Pacino) and Sal (John Cazale) as their planned heist goes awry and they end up taking the employees of the bank hostage for a long, hot Brooklyn afternoon. After generating both a neighborhood and media spectacle in which various onlookers seem to support their cause against the local police, their hostage drama ends with their demands having been seemingly met. The penultimate minutes of the film present them with their hostages at JFK airport. Having been given the jet that they demanded and preparing to fly to off Algeria, Sal is suddenly and unexpectedly killed by an FBI agent, after which Sonny, in shock, is summarily arrested.

Dog Day Afternoon, then, narrates at a basic level an attempt to capture money outside of the usual channels of formal work. As the narrative progresses and the state's response to the robbery intensifies — an intensification which the film highlights through its own proliferation of multiple shots and angles of the bank (from interior to exterior to aerial) — the film suggests that there is something deeply symbolic about the state's spectacular reaction. Namely, the amount of money spent on interrupting the robbery will likely be greater than the amount that would have been seized were the robbery to have been successful. The state wants to protect money but even more emphatically wants to protect the idea of money — to protect the idea that money can be protected. Yet in a period of inflation, it becomes less obvious that the state can protect money. In the words of Ronald Reagan, "inflation is as violent as a mugger, as frightening as an armed robber and as deadly as a hit man."18 According to Keynes, architect of the very economic system that was seemingly crumbling under 1970s inflation, inflation has the ability to produce a transformed social world of shifting orders and coalitions. Keynes writes:

As the inflation proceeds and the real value of the currency fluctuates wildly from month to month, all permanent relations between debtors and creditors, which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism, become so utterly disordered as to be almost meaningless.19

For Reagan, inflation is like an armed robber, but for Fredric Jameson the armed robbery on view in Dog Day Afternoon becomes a powerful way to render perceptible inflation as a historical problem. The setting of the bank and the plot of the robbery raise questions of class, money, and capital itself. In this spirit, Jameson has argued that Dog Day Afternoon can be read as an allegory of a changing class structure in the 1970s. He writes, "The film suggests an evolution ... in the figurable class articulation of everyday life."20 For Jameson, individuals now relate to capital on a newly global and corporate level. Thus he positions the anonymity of the multinational corporation against the local branch bank which Sonny and Sal rob and the overly embodied (always eating, always yelling) municipal police force against the deracinated, affectless FBI. Finally, he suggests, the suburban filmgoer consumes the alterity of an ultimately "homosexual" love story as she roots for Sonny, the gay bank robber. In Jamesonian fashion, these structural contradictions cannot hold, and they erupt in the film in the form of unmanageable symptoms that produce their own moments of historical truth. And what is that truth? Jameson describes a "society with a capital S" for which Watergate and Vietnam caused "the collapse of the system's legitimacy and the sapping of the legitimations on which it was based." Jameson then singles out inflation as a kind of optic for revealing historical truth: "the experience of inflation," he writes, becomes "the privileged phenomenon through which a middle-class suddenly comes to an unpleasant consciousness of its own historicity."21

In the 1970s, inflation provoked economic precarity in the middle class, perceived through stagnant wages. Likely outside of union protection, the middle class felt the squeeze first and had fewer resources to combat it. As employment dried up, their own class mobility was limited and they became sympathetic to the anti-labor discourse of inflation. As the economic historian Meg Jacobs has noted, "concern over inflation" hosted various "battles of class formation" throughout the decade. Indeed, Jacobs identifies inflation as the "Achilles' heel of postwar labor-liberalism," and further calls this economic phenomenon "the permanent dilemma of the middle class."22 Jacobs's claims, then, seem to support Jameson's contention.

Yet Jameson's article is, for my purpose, as much a historical source as an interpretative guide. Published in 1977, it was written in medias res in the story of inflation. Jameson introduces gender, race, and sexuality into his analysis of Dog Day Afternoon as possible interpretative categories, but he ultimately folds them back into a rather stale notion of class. Inflation is indexed to a certain class, i.e., the middle class, and while that class develops what would seem to be a contradictory attachment to a homosexual criminal, its own imbrication in historical contradiction does not extend to the working class. Likewise, while gender and sexuality are, like inflation, sites of historical contradiction, they are not sites of labor. As the film's narrative advances, it becomes clear that Sonny is robbing a bank because he cannot find union work, because he has a wife and children to support and because he has a "transsexual" second wife to support as well. His first wife needs what women always need: money for the daily reproduction of herself and her children; his second wife needs gender-conforming surgery; she cannot work and is "in hock." The nexus of work and wage cannot be separated from that of gender/sexuality.

If inflation is a symptom of labor reorganization that augurs the waning days of Keynesianism, and Keynesianism is itself a regime wherein certain forms of race and gender are organized via employment in the service of capital, then we will need to look to each of these categories as potentially available for reorganization. That the union-wage established both historical continuity and differential wage rates — a family wage for some, a meager wage for others is, at this point, a truism: the family wage was the male wage, the skilled wage, the "psychological wage" of race, in W. E. B. Du Bois's famous words.23 Here my focus is primarily on gender, and on the ways that — insofar as the wage measures and compensates gendered labor — we might read gender itself the materialization of a wage differential at a moment in time. A certain wage produces a certain gender; a different wage produces a different gender. A rejection of the normative categories of gender, as we will see in Dog Day Afternoon, may lead to wagelessness.

Before returning to the film, however, we must query the relations among gender, wage, and the tenuousness of the Keynesian order. Did changing gender categories relative to the ability to work cause inflation, as certain of the American neoliberals seem to suggest, or did inflation produce some flexibility in social categories of power, such as gender, as Keynes himself thinks possible?24 To claim, as I am, that inflation indexes a conceptual and material spread between labor's productivity and its price implies, of course, that there was once a connection between them. Indeed, the connection between periods of high productivity and a high wage share (and the assumption that lower productivity should lead to lower wages, lest inflation occur) is the central tenet of the Regulation School, which tends to subscribe to a "profit squeeze" theory of inflation (similar to wage-push). Regulation School accounts typically argue that the Keynesian demand stimulus and its goal of full employment inevitably leads to inflation, since it means there is inadequate flexibility (either economic or social) for firms to lower wages if productivity declines. In a similar light, Massimo De Angelis understands Keynesianism as an "expansionary strategy of growth ... that enables different interests to remain in balance" in a period of "social turmoil" — that is, as a political solution to emerging problems of class conflict — but one that can function only so long as class composition and the organization of labor looks as they had under Fordism. 25 Yet in the 1970s, class composition changed. De Angelis claims that "women's double work load, at home and in the factory, bec[a]me the condition for their everyday struggles. This connection between production and reproductive work would be one the major issues of the struggles of the 1960s, which would bring on the collapse of Keynesianism."26

These struggles between forms of paid and unpaid work as they relate to gender structure Dog Day Afternoon. A period of inflation intensifies and makes visible their constitution. Unlike Jameson, I do not see class as an overdetermining category of social consciousness, capable of enveloping sexuality and gender. Rather, I suggest that inflation forces a reconsideration of how certain specifications of labor are revealed to reflexively stabilize gender itself, as when gender appears as emotional labor. Allegory befits Jameson's insistent hope for a totality; but I look instead to genre, and to the manner in which Dog Day Afternoon — and, in the next section, American Dream — revise their genres by showing how the space between work and wage created by inflation focuses our attention on gender as labor.

In Dog Day Afternoon, the ability of the state to protect money and the chance for those outside the hegemonic social order to seize it take on both comic and dramatic dimensions. By the time Sonny and Sal get to the bank, most of the cash has already been collected for the day. Even in a bank there is no money. Yet while cash is the object of the robbery, the idiom through which the robbery is conducted is that of wages, salary and labor. All the characters in the film — the robbers as well as those who are present in the bank during the robbery and subsequent hostage-taking — perform white collar, non-unionized, professional or semi-professional service work.27 This is true of Sonny, the female bank tellers, the branch manager, and the police chief (who may be in the union but who here operates in a clearly managerial role). But they are service workers in an ambiguous moment: they are not necessarily working. Or rather, they are working at the film's beginning but as the robbery drags on, the female tellers, in particular, exist in a liminal time between work and non-work. They gossip, talk on the phone, perform faux military drills with Sonny's rifle, smoke, and so on. Their lightheartedness in the face of their kidnapping and potential death offsets Sonny and Sal's seriousness and intensity. For example, when Sonny is preparing to lock the women in the vault, one asks to use the bathroom. Sonny is both appalled — the bathroom? now? — but likewise accedes to her demand and asks, "Ok, who else has to use the bathroom?"

Fig. 3. Sonny with Female Hostages

What exactly are these women doing? The film's rigid gender binary — and its attempt to connect that binary to forms of work and compensation — will ultimately and dramatically come undone with the revelation of Sonny's homosexuality and his lover's transsexuality. But, for the moment, women are doing women's work and it looks very much like what Arlie Hochschild would soon describe as "emotional labor" in her groundbreaking 1981 book The Managed Heart: The Commercialization of Human Feeling. Examining the labor of primarily non-unionized, female flight attendants, Hochschild argued that workers in the service industry are often compelled to produce and communicate certain feeling-states as part of their work. In a service economy, she argues, "an emotional style of offering the service is part of the service itself, in a way that loving or hating wallpaper is not a part of producing wallpaper."28 Hochschild claims that how one feels on the assembly line — does one smile or frown, does one seethe with resentment or radiate appreciation? — does not matter to the assembly line. Her argument that emotional labor is gendered is equally relatable: women's work is the work of care, joy, or pain, of recognizing, processing, and metabolizing the feelings of others, whether children, family members, co-workers, or customers, what Hochschild describes as "the management of feeling to create a publicly observable facial or bodily display." Yet for all the truths of Hochschild's contention, there seems also to be a redundancy. Isn't it tautological to suggest that emotional labor is visible first among women since women are distinguished prima facie by being a certain kind of emotional creature?

Indeed, the film itself suggests a more complex reading of labor and gender. If the female tellers introduce emotional labor into the film, emotional labor ultimately finds its home in Sonny's actions, a gender shift which, for my purpose, both materially expands and conceptually limits the idea of emotional labor. In Dog Day Afternoon, the gendered dimension of labor can only become visible with the supercession of the wage. That supercession allows us to see that emotional labor is kind of a compromise formation, a way to talk about changes in labor that result from the wage but do not address it.

By contrast, the Endnotes Collective pursues a stronger argument about gender in relation to the wage in "The Logic of Gender." "'Sexual difference,'" they contend, "is produced by capitalist social relations" in order to keep women's wages low: due to the nature of the constructed category "woman," "capital can use women's labor in short spurts at cheap prices." This — not any specific qualitative character or affectation — is what defines "feminization": "cheap, short-term flexibilized labor-power ... increasingly deskilled and 'just in time.'"29 In his reading of Midnight Cowboy, Kevin Floyd likewise notes that within a Fordist regime of accumulation "masculinity is best understood as a certain type of skilled labor located at the moment of consumption rather than production."30 These theories are importantly distinguished by their insistence that gender may be understood as a form of labor and by the fact that they insist this largely without taking recourse to affect.

Dog Day Afternoon's tellers, robbers, and managers perform different work from one another. But out of that difference emerges a commonality that is both physical — everyone is trapped in the bank — and economic: no one is paid enough. The bank's manager, Mulvaney, says he won't be doing anything "heroic," to save either the bank's money or save his own life: "not on my salary," he quips. The teller "girls," meanwhile, have their own complaints. They eagerly volunteer that their own wages are unenviable, and when a news reporter asks Sonny why he doesn't simply "get a job," the tellers themselves seem sympathetic to his claim that with today's low wages, it's hardly worth the trouble.

We also, of course, have to inquire about a bank robbery's peculiar relationship to work. How should it be categorized? Is it service work? Emotional labor? Productive labor? The film offers a scene that orients our answer to that question. Halfway through the robbery, a news anchor speaks to Sonny on the phone while he is in the bank, holding hostages, gun in hand. As the camera zooms in through the sidewalk window, so that Sonny sees himself on television but is disoriented as to how this view is being generated, he is told by the anchor: "We're live, on the air." The anchor begins to interview him and asks, initially, "Why are you doing this?" Their dialogue then proceeds:

SONNY

Doing what?

TV NEWSMAN

Robbing a bank.

SONNY

I don't know... It's where they got

the money. I mean, if you want to

steal, you go to where they got the

money, right?

TV NEWSMAN

But I mean, why do you need to steal?

Couldn't you get a job?

SONNY

Get a job doing what? You gotta be

a member of a union, no union card —

no job. To join the union, you gotta

get the job, but you don't get the

job without the card.

TV NEWSMAN

What about, ah, non-union occupations?

SONNY

Like what? Bank teller? What do

they get paid -they pay one hundred thirty-five

dollars and thirty-seven cents to

start. I got a wife and kids. I

can't live on that.

The work of robbery is not union work, then. Perhaps it exists somewhere between blue collar and white collar, as it is both professional and a craft. Indeed, Sonny tells the bank manager: "I used to work in a bank so I know the alarms." For Sonny, the work of robbery needs to generate a family wage even as that construct is becoming obsolete historically. The newscaster's question — why are you doing this? — opens a space for Sonny to assert that robbery, not employment, is the path to money. For him, the possibility of a good paying job has been foreclosed — he is outside the union. As their conversation continues, Sonny becomes increasingly assertive. He can't get a union job — one that pays — and to get a non-union job is to be poorly paid. He then turns to the newscaster and asks what he gets paid, attempting to draw the anchor into common cause as another victim of the wage's obsolescence.

Sonny wonders to the newscaster: "We're hot entertainment, right? You got me and Sal on TV ... we're entertainment you sell, right?" As the newscaster corrects him and insists the unfolding drama is "news" not "entertainment," Sonny again asserts himself. He is working, the television stations are making money, his actions have preempted regular entertainment for which he is not being paid but for which everyone else in the mise-en-scene — police, news media, bank employees — are. "You payin' me? What have you got for me? We're givin' you entertainment ... what are you givin' us?" Sonny asks. "What do you want us to give you? You want to be paid for what...?" the newscaster responds.

Sonny claims that bank robbery shares elements in common with wage and no-wage work, as well as service work. More surprisingly, executing his constantly evolving plan also requires what we might recognize as emotional labor avant la lettre in a man who becomes feminized. As the union wage is eroded, the question of what precisely it indexes — gender and labor, gender as labor, unpaid labor — becomes newly urgent. When discourses of inflation offered the critique that wages were too high and should be renegotiated, they also implied that categories of gender and labor could be renegotiated. Early theories of emotional labor such as Hochschild's did not, of course, read gender as labor, nor did they wonder about wages as the price of work. But they did claim that certain types of work, primarily service work, done by primarily women, constituted a different and, as of yet, untheorized type of labor, one not fully able to be subsumed under the wage.

When Mulvaney, the bank manager, scolds Sonny for impetuously firing a shot into the bank's ceiling, telling him "that was a foolish thing you did," Sonny responds by foregrounding the emotional toll his robbery is taking on him. "You think it's easy?" he barks at Mulvaney. "I gotta keep them cooled out. I gotta keep all you people happy. I gotta have all the ideas and I gotta do it all alone. I'm working on it. You wanna try it?" This, of course, is precisely how Hochschild introduces the concept of "emotional labor": soothing people, anticipating their needs and anxieties, an occupation of one's mental and emotional life that cannot be captured by the wage because it is not understood as part of the work. For Hochschild, this labor is recognizably "feminine" because of women's propensity toward what Freud categorizes as a capacity for anaclitic love — the giving — as opposed to narcissistic love — the taking.31 Describing the work he performs in terms of emotional effort, Sonny seems to submit to the feminization of service work. Yet by acknowledging that emotional labor might consist not only in giving, but also in being willing to take — or steal — the film also arguably puts pressure on Hochschild's seemingly clear distinction between "emotional" labor (as femininized service work) and "productive" labor (as masculine industrial work).

For Hoschchild, again, "loving or hating wallpaper is not part of its production," but in fact, both love and hate are very much a part of what has been understood as classically "productive" activity. Citing the work of organizer and theorist James Boggs, Jason E. Smith notes that wildcat strikes at the height of worker radicalism in the 1940s and 1950s took many forms. "In 1943, a UAW-organized Packard plant was the site of a 'hate strike' organized by white workers to push back against the influx of black workers into the factories."32 Arguably, love and hate in this context are the affective responses to work, rather than — as with Hochschild's smiling stewardesses — the work itself. But the strategic deployment of hate by the union to defend and produce the family wage as an exclusively white privilege does suggest a link between emotional expression and the wage stability experienced by white, male, "productive" workers that a simple version of the "feminization" thesis conceals. Even as Sonny appeals for recognition of the emotional labor he undertakes, he refuses a separation between work and the emotional intensities produced through work in other sites as well. In talking with an FBI agent, he asks: "You'd like to kill me, right?" The agent coolly responds: "It's my job." But Sonny won't have it: "You know," he says to the agent, "the guy who kills me, I hope he does it because he hates my guts, not because it's his job." Here emotion and work might seem distinct: Sonny desires an emotional exchange, not a work-based exchange. But in hoping for a would-be FBI-killer who both produces work (assassination) at the same time as emotion (hatred), he refuses the idea that emotional labor and productive labor should be conceived as fully separable.

Sonny hopes to receive money outside of the formal wage structure, in part through expending emotional energy, but he must also labor to maintain his masculinity, since masculinity appears as a crucial component of the skill required to threaten, rob, take hostage, and perhaps kill. This masculinity is of course dramatically undermined by the revelation that Sonny is "a queer," and that he is undertaking the robbery for his transitioning lover. The robbery thus becomes, in the words of one newscaster, a "robbery in progress by two homosexuals." A "queer," Sonny desires money for his biracial "wife," Leon, who, we learn, is "a woman trapped in a man's body." Sonny is working for Leon, for Leon to no longer be a man, but to do so, Sonny must risk becoming emasculated. These are the twin axes of the film — the need for money constrained by the inability to work formally for it, and the need for masculinity as a platform to get that money with the full knowledge that the destination of the money will be a site of emasculation. Under these conditions, the film asks, how should labor be theorized? In capturing a break between labor and wage, Sonny and Sal's robbery exposes Sonny's "emotional labor," which Hochschild suggests extracts a toll not indexed to the wage. But, then again, he has undertaken the robbery because there are no wages to be had.

From The Godfather to Goodfellas, the genre of the crime film has long relied on the idea that the ability to seize money by illegitimate means requires an excess of masculine legitimacy (or that ability to seize money by illegitimate means confirms an otherwise vulnerable masculinity). In Dog Day that idea is reversed: an apparently illegitimate masculinity makes it possible to demand money outside of recognized labor structures, and an illegitimate romantic pair confirms that illegitimacy by one of its members participating in an illegitimate form of work.33 Of course, Sonny's attempt is ultimately a failed one: Sal is killed, Sonny is arrested, and both of his wives are abandoned. Yet that failure becomes the site that reveals the space between work and wage, and the modalities of work that result therein, in which we also find the generic break in this labor film.

Dreams of Industrial Labor

If the production of emotion and affect is to be considered a form of labor, it must also be possible to find these kinds of activities in organized labor, male labor, and productive labor as well as in non-waged labor, feminized labor, service work. American Dream, the second film to which I turn, captures the relationship between affective labor's intensities and no-wage work. As in Dog Day Afternoon, American Dream uses the representation of no-wage, gendered work to force a generic revision of its form, the labor documentary. Set in Austin, Minnesota in 1985-6 and released in 1990, American Dream followed Kopple's 1976 Harlan County, USA as part of a project of investigating organized, waged labor at its moment of signal crisis. American Dream opens with the all-too-symbolic image of swine being led to their slaughter. Before the first credits are presented, an industrial building is visible in a long exterior shot and then, with a quick cut to interior, its occupants are revealed: pigs, not workers, occupy the opening action sequences. The documentary's first minute tracks their electrocution, decapitation, dismemberment, and finally packaging for distribution and sale: we are inside the Hormel meat-packing plant, and ham and bacon are being prepared for shipment. Following the publication of Ross Thomas's 1973 novel The Pork Choppers, union leaders had been colloquially referred to as "pork-choppers" (by, for example, New York Times labor reporter A.H. Raskin) — Kopple's film does not make this connection explicit, but the suggestion that we may be watching the dismemberment of the union itself resonates.34 The film is periodized in its first few minutes with a simple textual declaration: "The Early Eighties."

American Dream tracks the struggle of the Meatpackers Union Local 9 as they receive the news of Hormel management's offer of a new contract: their wages will be cut from $10.69 to $8.00 per hour and new workers will come in under a tiered system. The International Meatpackers Union advises the local union to accept the contract, noting that wages are being cut industry-wide and asserting that one local cannot stem the tide of falling wages across the country. Yet Local 9 opts for a more confrontational response. First, they engage the services of a New York City-based labor consultant, Ray Rogers, and his firm, the Corporate Campaign. Second, they refuse the wage cut and opt to strike, a work action that takes some 26 weeks, the duration of which constitutes the majority of the film's narrative time. As the strike continues, Local 9's actions become both more militant and more desperate. At the film's conclusion, the wage cut has been partially but not fully reversed, a wage freeze has been enacted, and a tiered system will be introduced. With new workers earning less, future solidarity will be more difficult to achieve. Most dramatically, the over 1000 workers who either remained on strike or respected picket lines set up by Local 9 at other Hormel plants have been terminated and will not be re-hired. Kopple herself understands her film to be "about the Reagan Era, about wage concessions, and economic crisis."35 Indeed, the film stages the benefits and risks of a politics of the wage and, I want to argue, suggests the possibility of a shift to a post-wage affective labor.

Like Harlan County, USA, this film incorporates much of the nationalism, jingoism, and liberal ethical assessments common not only to what film scholar Paula Rabinowitz rightly calls "the sentimental contract of American labor films" but also to American progressivism itself.36 American Dream, as its title declares, is an American film. An American film — not to mention an American dream — need not be fundamentally heteronormative, white and male, but we cannot be surprised at the coincidence. In this respect, the film is of a different sort than the labor documentaries Finally Got the News and Who Killed Vincent Chin?, which refuse to see white nationalism as benign. Kopple's attachment to labor as a white, patriarchal formation must be troubled, of course. But it must also be understood to organize a cycle of analepsis on which liberal economic critiques so often rely: namely, that things were better then and that they are worse now. Indeed, the film's first speaker, a retired Hormel worker giving his support to current workers, simply says: "I wouldn't like to take a cut, either. We didn't have to." Of course in the end, those working at Hormel now do have to take a cut, and this narrative of decline structures the film.

Yet the time and space between then and now is not simply theorized, becoming instead the site for a liberal dialectic of loss and recuperation routed through the amount of the wage. The central conflict of the film is whether the unionized workers will accept a wage reduction, from $10.69 to $8.00 dollars an hour. Things were better, then, when the wage was high and when new contracts would see it rise increasingly higher. But why were wages high then? What made such a state of affairs possible? And why did that order crumble in the short span of a few decades? The film directly narrates the decline of wages and indirectly narrates the decline of power: We didn't have to accept low wages because we had power; You have to accept them because you don't. The film's dual stories of decline not only suggest that now the "American dream" has collapsed whereas before it was possible, they also suggest that wage gains and wage stagnation are directly and exclusively linked to the relative power of the union.37

A similar tendency to substitute narrative moralism for historical investigation haunts some of our most searing economic critiques of the present — I have made this claim about The Wire — as well as some of our most banal, as in Michael Moore's Roger & Me and Capitalism: A Love Story. 38 American Dream uses this moralism to represent the object of the film's drama, the Hormel company. The viewer is instructed that before its inexplicable turn to greed in the 1980s, the company offered " the [country's] first guaranteed annual wage increase [and] profit sharing plan." The film also notes that company founder, George A. Hormel, was "a born entrepreneur with a social conscience who showed concern for the working man." With profits still historically high, the film argues, the workers should continue to benefit. There is no reason to cut wages. Yet such a claim introduces its own worrisome sequence of reason, namely the inverse: when profits are low, then a cut makes sense. The subjects of Kopple's film reject the logic that ties their wages to profits. Regardless of the state of corporate affairs, to get higher wages, now, they must strike. That action requires temporarily abandoning all wages. While on strike, they will be without pay and that moment allows certain modalities and metrics of labor outside the wage form to become visible.

We might thus read the film as an exploration of changes in the representation of labor in the context of an expiring wage. In this regard, American Dream is similar to Dog Day Afternoon. The difference is that Kopple's film retains a focus on the union wage — the family wage — throughout. Only with the strike, when wages are not being paid, does a space open for different kinds of work: in particular, I want to suggest that affective labor emerges when the wage disappears. Of course, the kind of skilled, industrial, and organized white male work represented in American Dream is precisely the kind of work terms such as "affective labor" and "emotional labor" were meant to move beyond.

Both terms, Hardt's affective labor and Hochschild's emotional labor, emerge in an extended moment of crisis for the wage.39 Hardt sees himself as bringing together two forms of research: feminist scholarship like Hochschild's, about gendered forms of labor, and the work of Italian autonomists like Antonio Negri and Mario Tronti, who, since the 1960s, have used the language of "real subsumption" to argue that, to quote Jason Read, "there is no relationship that cannot be transformed into a commodity."40 Both terms also render theoretically rich the labor that is non-organized, non-male, non-productive, and non-waged. But while emotional labor was linked to love and hate, visibility and non-visibility, affect does not lend itself to such transparency. Affect's substance is its intensity, its anti-regulatory capacity, its ability to be transmitted without being located under a specific sign of love or hate, joy or sorrow, shame or pride.

It cannot be the case that affective labor is historically novel. Labor is a form of social abstraction that must not remain local to one population, one period, or one place. Here Hardt is quite clear: "I do not mean to argue that affective labor is new or the fact that affective labor produces value is in some sense new," he explains.41 This argument is important because all too often, claims about the supposed newness of a form of labor are made in place of arguments about the origins or consequences of those forms of labor, much in the same way the nostalgic analepsis in the film substitutes for an analysis of why things are worse now (and why they were better before). This doesn't mean nothing is new, however: as Hardt argues, affective labor today is newly "productive of capital" and newly "generalized through wide sectors of the economy."42 Then we must ask: why here, why now, and for whom does this concept emerge? In my reading of American Dream, I argue that affective labor becomes visible precisely as wages disappear.

Before the strike, essentially one kind of labor is on display: productive, industrial labor. Here, "work" means what it has almost always meant in political economy: man (and not woman) is separated from both nature and machine as he uses the latter to metabolize the former. The film doesn't merely "represent" this kind of labor; rather, films such as Kopple's have produced our iconography of what we mean by labor: Union. American. Rural. Skilled. White. Male. The narrowness and circumscription of the film may in this sense be read as a condensation of the wage itself, including its ostensible indexicality and universality.

In fact, however, precisely because the film seems to offer such a narrow and stereotypical rendering of labor, it also offers a compelling site to rethink and resituate both labor and the wage. For one thing, it becomes obvious over the course of the film that the real narrative tension derives from a series of conflicts around how and whether the wage is the only means and ends of class politics, as well as between and among different kinds of labor. There is union against management, of course, but there is also the local union against the international union. In Local 9, there are factions that organize against each other about whether to remain on strike or return to work, who remain in conflict about whom to ally with outside their local. And then there is the mercurial Ray Rogers, the labor consultant who becomes the focal point of the film's action as well as its multiple registers of labor, including not only unwaged labor but also affective labor and gender as labor.

Fig. 4. In American Dream, labor is coded as iconically masculine: Union. American. Rural. Skilled. White.

The rebellious Local 9 hires Rogers to lead its strike against both Hormel management and against its International Union. While Rogers is introduced as a "leading labor consultant," he is presented as diametrically opposed to what has up until this point signified labor in the film. The meat-cutters and the meat-cutting plant form the locus of laboring action in the film; Rogers is a vegetarian. Labor is rural, suffused with Americana; Rogers hails from New York City. Labor is physical, repetitive, attached to machines and animal bodies; Rogers flits around the country outsourcing his consulting services. In Rogers, a seemingly new labor emerges, one that arrives in the film at the moment when wages are suspended. He is thus key to the film's representation of affective labor and to the affects of labor, even as certain of the striking workers will likewise adopt this disposition toward quite different ends.

Though his efforts are ultimately destined for failure, Rogers successfully pitches his consultancy's services for hire to Local 9 by promising them value that far outstrips their wages and income. He begins by telling union members what he sees in them: "The greatest source you have is your people. We will run a million dollar campaign even though you don't have a million dollars." Here, the labor and its wage are as separate as they were in Dog Day Afternoon's scene of bank robbery: one can access a million dollars' worth of work without actually having a million dollars to pay in wages. Rogers then proceeds to sell his organization: "On our staff we have people experts, communication experts, experts in all aspects of community organization. We do research and analysis." Rogers lays out a plan of action, one that does not necessary highlight a withholding of labor — even though the union will be on strike, of course — but that instead emphasizes a public relations campaign. "If you can embarrass a company hard enough and long enough, you can bring them to their knees," Rogers extols. Rogers goes on to envision "real economic pressure, impenetrable, [made possible] through analysis," and "a million dollars worth of free and positive publicity." Note the repetition: again, a million dollars may be accessed without actually requiring the possession of a million dollars. I suggest we see this separation as a continuation of the break between wage and work — and between the real value of money and its price — that I previously connected to inflation and to the anxieties about the wage that attend it.

Rogers may be read as a site of affective production as it emerges from a post-wage moment. He offers a series of shifting intensities, yet those intensities do not redound to the wage. Likewise, Rogers's affective labor becomes a site of gender-production and redefinition. To be an affective laborer is to be a feminized laborer. Rogers is critiqued by those opposed to him in a sexualized language in which he is positioned as emasculated and overly embodied. Those who associate with him "stand around," according to the International Union's president, Lewie Anderson, passively "holding their dicks," while Rogers gives them a pitch for his services that is "shot through with shit"; his in-depth research and analysis, Anderson explains, has "about as much depth as piss on a flat rock."

Nonetheless, almost no one in the film who experiences his affect is unmoved by it. Indeed, one of Local 9's members who is opposed to Rogers admits to him: "you're one hell of a motivator, I'll give you that." Another of those opposed to his initiatives of publicity and performance concedes that Rogers infuses the local's union hall with a different kind of feeling. "Dancing, movies, singing, you should see what's going on there," this dissident member reports. He then adds: "that probably needed to happen anyway." Such affective intensity "needed to happen" because a union can't mount a strike without the extra-wage affects of anger, excitement, and so on. But the question is: even if this needed to happen, is it enough to make something else happen? Is it enough to make a claim on the wage form?

When Rogers is in the frame, the camera replicates some of what the union members describe as their experience of him: the quick cuts, the scenes of men and women together; the camera, too, becomes excitable in the presence of Rogers. Indeed, he proves indefatigable. When the strike has concluded with multiple concessions on the union's part, and certainly some of the worse predictions have come to pass — "they won't win, they'll just be bigger losers," Lewie Anderson had predicted — Rogers persists and concludes of the strike that it has introduced a "a set of dynamics that cannot be considered anything but positive." In retrospect, that incorrigible positivity is indeed one of the things, if not the main thing, Local 9 purchased from Rogers. They may have thought they were purchasing the ability to win but, in fact, they were purchasing a different dimension of the very labor they withheld while striking.

Others of the film's cast cycle through different forms of un-waged, feminized work and, as in Dog Day Afternoon, the representation of those forms forces the film's generic revision. Particularly noteworthy are those strikers who ultimately make the decision to abandon Local 9's strike, cross the picket line, and return to work. These are waged workers who have cycled into a position of wagelessness. Without wages, they became less manly; they sit for interviews and tearfully recount how it feels to be "unable to provide for [your] family" and how it feels to lose the "pride you have in being a breadwinner." As Rabinowitz has suggested, this moment offers an interesting inversion in the genre of labor film, which tends to stake the viewer's sympathetic and sentimental connection with those who sacrifice for the cause, not those who betray it.43 As these men cry into their hands and turn away from the cameras, they both enact a feminized affectivity as well as show that some can chose to leave that state, to return to work, and thus to return to being waged. Now, however, such actions come at the expense of others.

By the film's end, it's not only that Local 9 lost the strike, that strikers were fired, that workers had to accept the wage cut and then wage freeze, but the local too has lost its autonomy: the leaders of the local are disenfranchised by the international and replaced. Such a strike won't be happening again. The union hall, once a place of joy, is shown at the film's conclusion with its doors shuttered and locked. The International Union proved correct: the strike failed because "one local can't stem the tide of a whole industry," and the industry of hog cutting, like the American economy itself, was following a tide that was moving in one direction: toward lower wages.

Conclusion

What Clough terms the affective turn was a needed and necessary intervention into how and why we work, as well as how and why such work is represented back to us as in the process of subject formation. By calling for an effective turn, I mean to both complement and to critique emotion and affect as a site of labor definition and revision. I hope other scholars will entertain certain questions like: Why did theories of emotional and affective labor emerge at a historical moment of crisis for the wage? Why did they require the new and expansive presence of women in formal labor situations, as was seen in the 1970s? How does understanding gender as labor place us on surer conceptual footing to evaluate labor's composition than gendered labor?44 What is the relationship between such theories and actually declining and/or stagnating wages?

Whereas Dog Day Afternoon might be said to have participated in a genuine generic transformation of the crime film — it pioneered the queer criminal, a figure that continues to shape the crime film — American Dream occupies an opposite position in its generic lineage. It represents the closing moments of a certain labor film because it represents the closing moments of representation of a certain kind of labor itself, while throwing the gendered component of that labor into relief. Between the generic shifts in these two historical labor films we note a change in the identification and description of labor as emotional or affective. What that does not mean, however, is that labor has changed.

Leigh Claire La Berge is assistant professor of English at the City University of New York (BMCC). She is the author of Scandals and Abstraction: Financial Fiction of the Long 1980s (Oxford, 2014) and the co-editor of Reading Capitalist Realism (Iowa, 2014). Her articles on the political economy of culture have appeared in American Literary History, Criticism, Postmodern Culture, South Atlantic Quarterly, and the Radical History Review.

References

Thanks to Annie McClanahan for inviting me to participate in this much-needed special issue; "editor" is not expansive enough a term for her labor in helping this article to see the light of day. Thanks, too, to two anonymous reviewers whose criticism, suggestions and encouragement quite literally made this essay possible. I hope they will see the results of their generous comments herein.

- As the recent twelfth edition of The State of Working America noted, "Wages were relatively stagnant for low- and middle-wage workers from 1979 to 2007 (except in the late 1990s), and incomes of lower and middle-class households grew slowly." See Lawrence Mishel, Josh Bivens, Elise Gould, and Heidi Shierholz, The State of Working America (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2012), 5. Similarly, the labor historian Lane Windham has succinctly offered her own estimation of wage growth: "Never again would production and non-supervisory workers take home as large a weekly paycheck in real dollars as they had in 1972." Lane Windham, Knocking on Labor's Door (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 5. That could be compared to a 67 percent increase in the postwar years.[⤒]

- See Elizabeth Bernstein, Temporarily Yours (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007). [⤒]

- [⤒]

- For the tautology inherent in periodizing attempts, see James Chandler, England in 1819 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998). [⤒]

- For the purposes of this essay, I will understand work as a local action in which we all engage to make our lives both meaningful and possible and labor as a coordinated social abstraction through which our work is organized. I take my lead not from Hannah Arendt, but rather from Moishe Postone in Time, Labor and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx's Critical Theory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993). For Postone, labor in capitalism, indeed, labor and capitalism, are historically unique. While "work" — the organization of reproductive tasks — is required for all humans at all times, labor under capitalism possess a global, abstract quality that was not present in previous organizations of economic life. Work is an action; labor is an abstraction. [⤒]

- The genealogy of the emergence of "affective labor" is impressive. See, for example, The Affective Turn, ed. Patricia Clough (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007); see also Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000) for their cognate term "immaterial labor" as well as their own genealogy of "affective labor." I will consider both of these concepts herein. [⤒]

- This is a project I began with my recent essay "Decommodified Labor: Periodizing Labor After the Wage," and here I continue to track this problem into the field of representation. Leigh Claire La Berge, "Decommodified Labor: Conceptualizing Work After the Wage," Lateral 7.1 (Spring 2018). [⤒]

- The qualifying adjective "effective" refers of course to "effective demand," a Keynesian construct that seeks to delimit at what level aggregate consumption of goods and services generates demand for labor, otherwise known as employment. According to Geoff Mann, "Effective demand is the centerpiece of Keynes's attempt to grasp how the volume of employment is actually determined in the economic society in which we actually live." Geoff Mann, In the Long Run We Are All Dead: Keynesianism, Political Economy, and Revolution (New York: Verso, 2017), (Kindle Locations 3710-3711). [⤒]

- Andrew Sernatinger and Tessa Echeverria, "'The Making of Capitalist Patriarchy': Interview with Silvia Federici," Feb. 4, 2014, accessed Dec. 2018. [⤒]

- The best critique of this logic is found in Michael Tratner, "Derrida's Debt to Milton Friedman," New Literary History 34.4 (2003): 791-806.[⤒]

- While there are various explanations of the causes of inflation, for me, the cause is less important than the effects. Was the chief inflation driver in the 1970s the Vietnam War, the rise of Japanese and Western European manufacture, or, as Hayek suggests, the fact that paper money will always have inflationary effects? This essay is not the place to answer that question, but rather to note the diversity of possible responses.[⤒]

- Michael Denning has suggested that film is crucial to capturing labor in the 1980s in his Culture in the Age of Three Worlds (New York: Verso, 2003).[⤒]

- Archie Bunker season 3, episode 1 in 1974 opened with an episode about unions and inflation.[⤒]

- As Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan rightly argue, "Inflation is neither the consequence of market imperfections, nor the result of misguided policies, but rather part of an ongoing restructuring of capitalist society ... inflation is in fact a mirroring of social relations, a projected image of the underlying struggle to reshape the broader system of power." Shimshon Bichler and Jonathan Nitzan, The Global Political Economy of Israel, (New York: Pluto Press, 2002), 170.[⤒]

- Melanie McAlister has done a wonderful job of reading the representation of the Middle East, its oil production in particular, as a cultural force throughout this decade. Melanie McAllister, Epic Encounters: Culture, Media and US Interests in the Middle East (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001). [⤒]

- Melinda Cooper, Family Values: Neoliberalism and the New Social Conservatism (Brooklyn: Zone Books, 2017), 25. [⤒]

- On Dog Day Afternoon and the changing genre of the crime film in reference to gender and sexuality, see Neal King, "Dead-End Days: The Sacrifice of Displaced Workers on Film," Journal of Film and Video 56. 2 (Summer, 2004): 32-44. [⤒]

- Reagan quoted in "Conservatives Mounting Coordinated Assault Against Democrats in Congress," Los Angeles Times, Oct. 22, 1978, 16.[⤒]

- Keynes in De Angelis, 15.[⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, "Dog Day Afternoon As a Political Film," College English 38.8 (April 1977): 843-859 [⤒]

- Ibid., 850.[⤒]

- Meg Jacobs, "Inflation: 'The Permanent Dilemma' of the American Middle

Class," in Social Contracts Under Stress: The Middle Classes of America, Europe, and Japan at the Turn of the Century, eds. Olivier Zunz, Leonard J Schoppa, and Nobuhiro Hiwatari (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002), 135. [⤒]

- David Roediger popularized the term "wages of whiteness" in his book of the same name, but the concept of "the psychological wage" is W.E. B. Du Bois's term, which Roediger cites. See Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness (New York: Verso, 1991) and Du Bois, Black Reconstruction (New York: Free Press, 1998). [⤒]

- Keynes does not single out gender per se, however he does say that forms of debt and credit, "which form the ultimate foundation of capitalism," become increasingly tenuous. Following scholars such as Miranda Joseph and Annie McClanahan's work on the sociality and relationality of debt, it seems fair to me to read this into Keynes's concern here.[⤒]

- Massimo De Angelis, Keynesianism, Social Conflict and Political Economy (London: Palgrave, 2000), x. [⤒]

- Ibid, 54.[⤒]

- For the broadness of this category, see Jason E. Smith, "Nowhere to Go: Automation Then and Now," in The Brooklyn Rail, March 1, 2017.[⤒]

- Arlie Russel Hochschild, The Managed Heart (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981), 6.[⤒]

- See The Endnotes Collective, "The Logic of Gender: On the Separation of Spheres and the Process of Abjection," Endnotes 3 (September 2013).[⤒]

- Kevin Floyd, The Reification of Desire (Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 2009), 155.[⤒]

- Thus, Lauren Berlant begins The Female Complaint (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008) 1, with the claim that "love is the gift that keeps on taking." [⤒]

- Jason E. Smith, "Nowhere to Go.," in The Brooklyn Rail, Mar. 1, 2017, accessed Oct. 2018. [⤒]

- This use of the queer robber as a site of generic break in crime melodrama is now a well-recognized move, one that both The Sopranos and The Wire use to craft their own generic revisions of the mafia and urban crime narratives, respectively.[⤒]

- Raskin cited in Windham, Knocking on Labor's Door, 58. [⤒]

- ary Crowdus and Richard Porton, "American Dream: An Interview with Barbara Kopple," Cinéaste 18.4 (1991): 37-38, 41.[⤒]

- Paula Rabinowitz, "Melodrama/Male Drama: The Sentimental Contract of American Labor Films," in Black & White & Noir America's Pulp Modernism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), pp. 121-142.[⤒]

- Negri himself reads the Keynesian moment differently: as a cooptation of working class power that was represented to the working class as an expression of their agency and power but in fact marked the attenuation of both. Toni Negri, Revolution Retrieved: Writings on Marx, Keynes and Capitalist Crisis, (London: Red Notes, 1988). [⤒]

- See Leigh Claire La Berge, "Capitalist Realism and Serial Form: The Fifth Season of the Wire," in Reading Capitalist Realism, eds. Leigh Claire La Berge and Alison Shonkwiler (University of Iowa Press, 2014). [⤒]

- See Michael Hardt, "Affective Labor," boundary 2 (Summer 1999): 89-100. [⤒]

- Jason Read, "A Genealogy of Homo-Economicus: Neoliberalism and the Production of Subjectivity," Foucault Studies 6 (2009): 25-36, quotation p. 29.[⤒]

- Hardt, "Affective Labor," p.97.[⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Rabinowitz, "Melodrama/Male-Drama," 121-142.[⤒]

- For a more recent theorization, that argues not only that labor has gendered dimensions or aspects, but that gender is itself a kind of labor, see The Endnotes Collective, "The Logic of Gender: On the Separation of Spheres and the Process of Abjection," Endnotes 3 (September 2013). [⤒]