How We Write (Well)

Let me begin with a true story: when I was teaching in Berlin, a colleague there shared his lecture notes with me for a large introductory seminar. I couldn't believe it when there between the glosses of Adorno and the pop culture references, I saw in bold letters "Pause for laughter." When I asked him about this, laughing myself, he said to me very earnestly "Ugh, it's the worst!! Sometimes the students don't laugh and then the timing of my lecture is all messed up!!"

One reason why those notes and my colleague's response still make me laugh is that the story bespeaks some kind of genre error. Although many of us strive to be funny in our lectures or witty in our writing, it's something that goes unspoken, and the effort behind the humor certainly isn't meant to be seen, let alone typed onto the page. Scholarly writing can be lyrical, clever, pithy, and impassioned, but it is rarely funny. An obvious reason for this is that attempting to be funny entails a serious risk: if there's something worse than having an argument deflated by a piercing question or the second reader's report, it's having a joke totally bomb. More to the point though is what I called a genre error: serious scholarship entails serious arguments and serious analysis and it's all very serious. But we can likely all name scholars whose writing we find funny and moments in texts that make us laugh—here's one of mine.

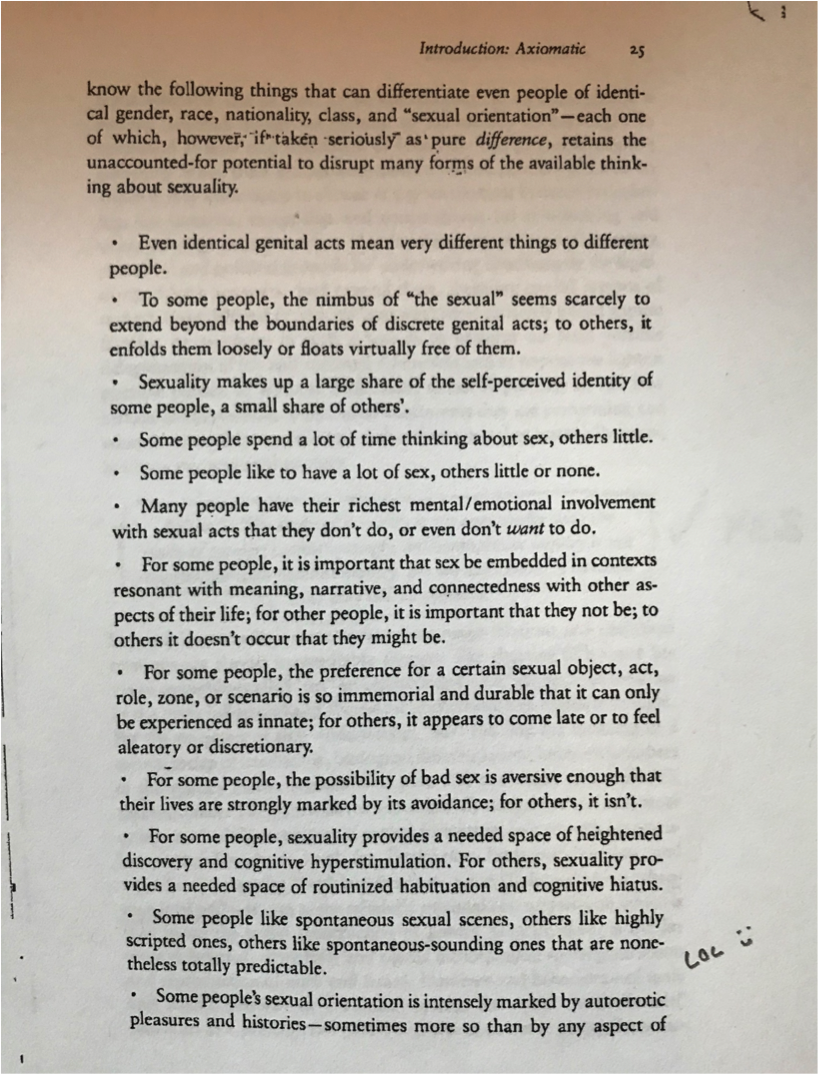

This is one of Eve Sedgwick's trademark lists from Epistemology of the Closet. It's a funny list because it's so long, so unexpected, and so true. We recall such moments of humor in academic writing because they are uncommon, but also because humor can reinforce an argument—it can even make an argument by pushing against readerly expectations and scholarly norms.

I'm not going to taxonomize humor and differentiate its various forms here: the joke, wit, irony, wordplay and so on. Fran McDonald has written about the different types of laughter present in and generated by post-war American literature, and I'm interested in whether this forum might allow us to think about whether or not literary criticism might reverse her formulation of "laughter without humor," giving us instead "humor without (much) laughter." That sounds like just another name for failed humor, but perhaps in the rest of this short essay I'll make the case that it could be something else. For now I'll just say that when I talk about "writing funny," I have in mind the kind of wit that does rhetorical work to convince a reader, bringing her along, making an argument by making her laugh (or at least smile).

This is the kind of funny I tried to be in a short essay I wrote about my objections to Object-Oriented-Ontology. The Essay, titled "My Problem with O-O-O, or Reflections on a Nugget," appeared earlier this year on the Stanford Arcade blog. In it, I try to take seriously a silly object I encountered at Elsewhere, a museum in Greensboro, North Carolina—a McDonald's "nugget buddy," which was included in Happy Meals in the late 1980s. The object itself is funny (at least I think so), as you can see in these amazing photos taken by Imani Thomas.

The short essay uses this weird object as its jumping off point, and it's really a reflection on how my mother's schizophrenia has shaped my thinking about agential objects and my critique of the new materialisms. Before I say any more about all this, let me just turn to the bit I want to share as my instance of "good writing":

This nugget is naked, his (her?) scuba mask, firefighter's mask or gunslinger's belt and lasso long lost to the ravages of time. But even McNude, the nugget captivated me. I spotted it peeping out from among piles of objects, beckoning me, calling forth the perverse innocence of a childhood in the 1980s, a time before I knew how little chicken was in those nuggets, before I knew that whatever meat was in there was processed in horrific conditions, washed with ammonia and plied with chemicals to give it its chicken-like appearance and flavor.

Isn't it strange to process a live animal into a nugget, something utterly inorganic, only to reanimate it for children as a sympathetic friend or action hero? Why anthropomorphize the nugget? Why turn it into "a buddy?" I guess it makes some kind of marketing sense, lodging the chicken nugget deep into the child's psyche so that she craves the food, the toy, the food-toy as companion. The smiling McNugget stands courageously against the army of undesirable adult food: the menacing broccoli, the duplicitous bran muffin, the odiferous fish. With no eyelids to close or limbs that might allow him to run away, this plastic warrior is on constant watch. And of course there is also the logic of the set or series, motivating the consumer-child to collect each variation on the nugget theme. But this particular traveler is alone, washed up on Elsewhere's shores like a relic of a fast-food obsessed people who perished from their bad habits before their successors could discover kale and quinoa.

This isn't laugh-out-loud funny, but I tried to allow for the absurdity of the object to come through in my writing. More than that, the humor is meant to temper what follows in this essay—the confessional bit about my mother's illness and about how it made her believe things were alive in frightening and dangerous ways. This isn't something I talk about with many people, and writing about it—putting it out there for anyone to read—felt terrifying. So humor here was a shield: it was a hedge against my vulnerability and also a way to avoid a 'woe is me' tone. This aligns with Bergson's notion of humor as "a momentary anesthesia of the heart." Humor's appeal, he writes in his essay on laughter, "is to intelligence, pure and simple."1 But in fact, in the context of my essay, humor isn't so much an appeal to intelligence as it is to empathy. I am asking my readers to laugh at my text so they might laugh with me, and in doing so find that we share common emotional and intellectual ground.

Bergson, Freud, and the Italian dramatist Luigi Pirandello all stress the social dimension of humor—the way that it is relational and depends upon mutual understanding. Humor, when it works, should bring people together. Perhaps this seems obvious, but the link between humor and empathy is not always so readily visible, in part because the link between humor and anger has much more traction. Many if not most famous comedians—George Carlin, Andy Kaufman, Chris Rock, Dave Chapelle— they make comedy out of anger, transforming their rage at the world and themselves into comic material. Although "angry funny" can also entail a plea for empathy, it's not the kind of humor I'm currently drawn to, or the kind of humor that I want to use in my writing. I'm here for the anger, don't get me wrong, but as far as humor goes, it's empathetic humor that interests me—that may be drawn from anger but works to transcend it, to bring others on board. Such humor is, to my mind, collaborative, compassionate, and feminist. My first example was Eve Sedgwick, and I'm thinking also of Hannah Gadsby's Nanette—furious, painful, but explicit in its attempt to make viewers laugh SO that they feel. "Why is insensitivity something to strive for?!" she asks about halfway through her performance.2

Scholarship—academic writing—is, we've been told, supposed to be dispassionate. It's supposed to be characterized by intellect, reason, rationality, logic. But what we're seeing as scholars publish in different venues and try on different voices is that rigor and humor and empathy are not mutually exclusive. Academic writing doesn't have to be a container too rigid for levity or for feelings. We have writers who have proven this to us, but it seems nonetheless something that needs proving time and again. If we believe that the novels, plays, poems, and films we study can foster connection, why shouldn't our scholarship do the same?

I was asked recently by a senior, male colleague if "empathy was really the hill I wanted to die on." Given all the smart critiques of empathy that had been made, he said, surely I might want to reconsider my commitment to it? I demurred at the time, but today I'm ready to say: YES. I will die on that hill. I'm desperate to see more empathy and compassion on the page, in our profession, in politics, and god knows online. If the scholarly publication game is beginning to change, might we challenge ourselves to infuse our criticism with the wit and kindness that we encounter in so many of our most treasured objects of study?

Or, well, let me ask: Did you hear the one about the academic who never needed to apologize for being funny or for being empathetic?

Sarah Wasserman is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Delaware, where she teaches course on 20th and 21st century American literature, material culture studies, literary theory, and media studies. She is currently finishing her first book, The Death of Things: Ephemera in America, which examines literary representations of ephemeral objects in American culture from the beginning of the twentieth century until today. Her work appears in Contemporary Literature, Modern Fiction Studies, The Journal of American Studies, and Literature Compass. She co-edited Cultures of Obsolescence: History, Materiality, and the Digital Age (2015) and curates the "Thing Theory and Literary Studies" colloquy on the Stanford Arcade website.