Issue 6: Midcentury Design Cultures

To start, two Chicago-based designs on paper as material and medium (figure 1). In 1940, Hungarian multimedia artist, educator and Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy published a brief article, "Make a Light Modulator," in the amateur photography journal Minicam. Photographs document a humble sheet of paper's transformation into a sculptural medium capable of endless formal values and varied emotional effects on its viewer. This is apt (figure 2). At Moholy's School of Design in Chicago, founded as the New Bauhaus in 1937, light modulators were fashioned to train students in the principles of photography and cinema — media whose revolutionary potential inhered in their basis in light (figure 3). Whether modulated by a sheet's artful cuts and folds, or serving as the photosensitive base of Moholy's photograms, paper work was at the core of the designer's humanist media pedagogy. Like light or even plywood, the plasticity of paper for Moholy was biosocial and therapeutic in effect, awakening emotional capacities stunted by modernity's regimes of specialization. In this way, as Moholy explained in his crucial midcentury treatise Vision in Motion (1947), his design pedagogy at the School of Design became democratic knowledge work, vital in wartime and postwar conditions (figure 4). It aimed to develop what Moholy conceptualized as a "new kind of specialist" in the postwar period, both flexible and adaptable—one who "integrates his special subject with the social whole."1 These integrated citizens were equipped with the faculty that Moholy dubbed "vision in motion," a bio-propensity for "seeing, feeling and thinking in relationship and not as a series of isolated phenomena."2 Paper was one medium of holistic relationship-seeing.

Another riff on a similar idea: consider the opening of designer and filmmaker Rhodes Patterson's industrial film, The Packaging System (1963) (clip 1). The 30-minute film, produced by the Advertising and Public Relations Department of the Container Corporation of America (CCA), begins with a split-screen drama of two actions — resource extraction and end use — that constitute packaging as an integrated system. The sequence frames the industrial production of paper as a complex managerial and administrative process, unfolding from forest to kitchen. In its preoccupation with the systemic functioning and integrated complexity of actions along the production-consumption circuit connecting material, structure, research, machinery, graphic design, printing and production, and marketing — Patterson's film offers its own form of what Moholy called "thinking in relationship" in its hymn to globally produced and distributed components: "each related to all; all related to each" (figure 4).

Unlike Moholy-Nagy, whose celebrated career has recently received significant scholarly attention and major retrospectives worldwide, Patterson's name is absent from accounts of modernism at midcentury, design histories of the Cold War, and standard studies of amateur or industrial filmmaking in the postwar era.3 Yet Patterson's films were situated at the heart of an ambitious campaign to bring modern design into the ambit of a corporate aesthetics. Trained at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1930s when émigré Bauhauslers were finding their way to political reinvention in the U.S., Patterson served as a reconnaissance photographer in WWII, and then returned to Chicago where he worked for several decades at the CCA during a period in which Chicago established itself as the Hollywood of nontheatrical film.4

At Container, beginning in the 1950s, Patterson made dozens of industrial films about the firm's operations and products; training films for new workers; and films documenting CCA sponsorship of management seminars and wide-ranging cultural activities.5 The CCA, as we'll see, had begun to think hard about the status of film in what Adorno, in 1960, called "an age of integral organization" defined by the "the present-day proximity of the concepts 'culture' and 'administration.'"6 Moholy and Patterson's overlapping designs on paper as integrative media attest to this conceptual intimacy — culture/administration — forged in and around the CCA's pulp, paper, and packaging empire, and through the labors of its visionary Chicago-based founder: the industrialist and arts patron Walter Paepcke. It was Paepcke who helped attract Moholy to the New Bauhaus under the aegis of the Chicago Association of Arts and Industries, and was a tireless advocate and financial supporter of Moholy's media-pedagogical program, which overlapped with Paepcke's own cultural-reform ambitions.

In this context, modern designers who worked for Container like Herbert Bayer, Herbert Matter, or Gyorgy Kepes, and filmmakers like Rhodes Patterson became humane poets of cardboard, maximizing its communicative value across media. Braiding the work of filmmaking, packaging, and design into its deeper, more philosophical investment in the project of communication, the CCA kept faith with communication itself as the "invisible infrastructure" of postwar liberal internationalism.7 In fact, Paepcke's firm reimagined the expansive work of packaging at precisely the moment that communication studies emerged as an academic discipline in the U.S., and the CCA's own cultural ambitions and design program intersected with the rise of the postwar "communications complex."8 The firm's midcentury operations allow us to consider the place of cardboard in the broader cultural and ideological work that Arvind Rajagopal has dubbed Cold War "communicationism." Marked by a fervent belief in communication as a "political and ethical ideal," communicationism wedded liberal humanism to the "free flow" of information and promoted the "communications revolution" worldwide as a developmental project of U.S-led modernization around the globe.9 If, as a range of scholars have variously shown, the Cold War-era fascination with communication laid the groundwork for another interdiscipline later called "media studies," the case of the CCA allows me to begin to write a media history of the cardboard box rooted in its communicative potential at midcentury. At Paepcke's CCA, the humble medium of cardboard became an interdisciplinary technical object, situated at the core of a sweepingly ambitious modern design program that united packaging and corporate humanism as primarily logistical enterprises.

As part of this integrated design program, Patterson's CCA films constitute one unacknowledged record of what I'll call midcentury container culture. By this, I mean both the firm's administration of culture at midcentury across a variety of overlapping ventures and the versions of corporate humanism and corporate personality cultivated within the distribution and communication network of the cardboard box. At the CCA, industrial filmmaking was conceptualized and practiced alongside the communicative work that the containers were already performing — as media of transport and information, shapers of public opinion and consumer desire, and means of targeting attention — under the aegis of the design department. In folding filmmaking into the packaging ambitions of its design program, the CCA turned to film as a communicative medium, but also as a managerial mode of what John Durham Peters calls "logistical media," whose job is "to organize and orient, to arrange people and property, often into grids," whether by maps or clocks, indexes or industrial films.10

Like the CCA and its cultural ventures, Patterson's films appear near the tail end of what media historian Alexander Klose has dubbed the second phase of "the history of the container."11 As Klose periodizes it, this liminal period — between the mid-nineteenth century and the end of the 1960s — witnessed the "conceptual and technical requirements for the modern container as the standardized medium for the mechanical processing of transport within an intermodal system."12 Patterson's CCA films document the midcentury transformation of distribution networks towards "the total mobilization of inventory" that constitutes contemporary globalization and the primary unit of its logistical system: the standardized, intermodal shipping container. Beyond that though, as documents of boxes, their human cultures of packaging, and their technical systems, Patterson's films functioned in the broader context of the CCA's organizational approach to media and culture. They cemented the longstanding relationships between the firm's logistical imagination, its commitment to a modernist aesthetics, and its postwar agenda of global humanism. And they ask us to consider how and why the CCA's philosophical inclinations and its humanities programs, as chronicled by Patterson, might assume the shape of a logistical endeavor, integrated by good design.

In what follows, I explore the role of film in the CCA's packaging and design culture, beginning with the wartime urgency of its logistical efforts, and moving through its postwar maturation in a few of Paepcke's various cultural reform initiatives and humanities ventures in and around Aspen, Colorado. The archival record suggests that film was conceptualized as part of the CCA's promotional efforts from as early as 1949. That year, the Hungarian-born filmmaker and photographer Ferenc Berko drafted a lengthy memo on a proposed "documentary or semi-documentary" film or series of films for Container, and included a three-page synopsis of one film.13 Berko, a friend of Walter Gropius and Moholy-Nagy, taught film and photography at the Institute of Design following Moholy's death in 1947, before relocating to Aspen at Paepcke's invitation to work on retainer as the primary photographic chronicler of Aspen's cultural activities.14 Importantly, in pitching a container film, Berko was inspired by the "unobtrusiveness with which the sponsor's name is used" in the "best advertising or public relations films produced in England during the last fifteen years," which presumably meant John Grierson's legendary work with Stephen Tallents at the G.P.O. Film Unit.15 Inspired by many of the G.P.O. films, Berko proposed "a film which would be of general interest, and which would show, in an interesting, informative, yet informal way, that the organization of the container industry and the whole process of the manufacture, design, and distribution of containers is a fascinating subject of great interest and even beauty."16

While I have found no record of Berko's CCA films, his interest in film as an instrument of enlightened public relations, and his connection to the School of Design, Moholy, and Paepcke indicates the tight relationship between the communications environment in which the paperboard box was conceptualized by both Paepcke and the CCA Design Department and the wartime work of Moholy-Nagy's school. As Berko knew well, at the School of Design (as of 1944, the Institute of Design), film was understood as part of an integrative design agenda and a vanguard humanities curriculum, but also as communications tool and a mode of public relations for a chronically underfunded school increasingly aware that its survival depended on its ability to intervene in a competitive attention economy. This awareness was sharpened by period-specific approaches to communication and propaganda with which both Paepcke and Moholy were familiar. These wartime lessons in communication transferred directly into the CCAs postwar economic and cultural ambitions, intertwined as they were, and fueled the CCA's use of film as a promotional device and its very conceptualization of the medium within a broader landscape of communications media that included the cardboard box. Managing that media landscape, and managing populations through deft packaging, was also the remit of the postwar corporation, and part of the CCA's expanded horizon of responsibility, as Paepcke understood it, and as it was debated in Aspen and elsewhere. By examining the place of film in the CCA's design program, I follow Klose's provocative insight that containerization, while supporting "significantly a system of production and consumption that circles the globe, leaving almost no place on early untouched," is also a "prevailing cultural technology of the 20th and early 21st centuries."17 As such, and as the designs of Paepcke's CCA on the postwar world made clear, the study of containers — and container films — cannot simply be an investigation of goods or the "logic of modularization and optimized distribution called logistics."18 Containers "play as decisive a role in the organization of people, programs, and information as they do of goods."19 Perhaps nobody knew this better than Walter Paepcke, erstwhile king of cardboard.

"A Boxmaker interested in Philosophy": Walter Paepcke's CCA

Founded in 1926, Paepecke's CCA was an organization built on the industrial-scale manipulation of paper — specifically, paperboard and cardboard, largely in the form of mass-produced paper boxes, from corrugated shipping containers to folding cartons and fibre cans encasing all manner of consumer objects. A second-generation Prussian, Paepcke had inherited his father's Chicago Mill and Lumber Company, a maker of wooden boxes and packing cases that had been "forced to add a paperboard box division" to follow the industry's steady shift from wood to paper as the cheaper and more flexible transport medium.20 Cutting loose the paperboard division and joining it with two other companies, Paepcke built the CCA amidst the "packaging revolution" of the 1920s and 30s. Spurred by what design historian Arthur J. Pulos described as the "dramatic increase in mass advertising made possible by radio, color illustrations in nationally distributed magazines, and the establishment of major news agencies, all of which helped bring Americans into a homogeneous common market," the packaging revolution was an effect of epochal changes in the landscape of industrial media distribution.21 Packaging quickly spawned what Neil Harris characterized as a "whole culture" in the U.S., becoming the site of a particular kind of interdisciplinarity in a new professional culture of consumption where "where artists, engineers, printers, industrial designers, merchants, manufacturers, and advertising agents met." 22 The culture of packaging included trade journals like Modern Packaging (founded in the 1920s), Packaging Review (founded in 1933), and Packaging Parade (first published in Chicago in 1938), and specialized conferences. The first Packaging Conference, Clinic, and Exposition was hosted in New York City in 1931, sponsored by the American Management Association, and the second was held in Chicago in March of 1932. The Third Coast, Chicago, with strengths in wood, paper, metal, and cardboard industries, was thus a central "node" in packaging's dynamic growth in the interwar period.23

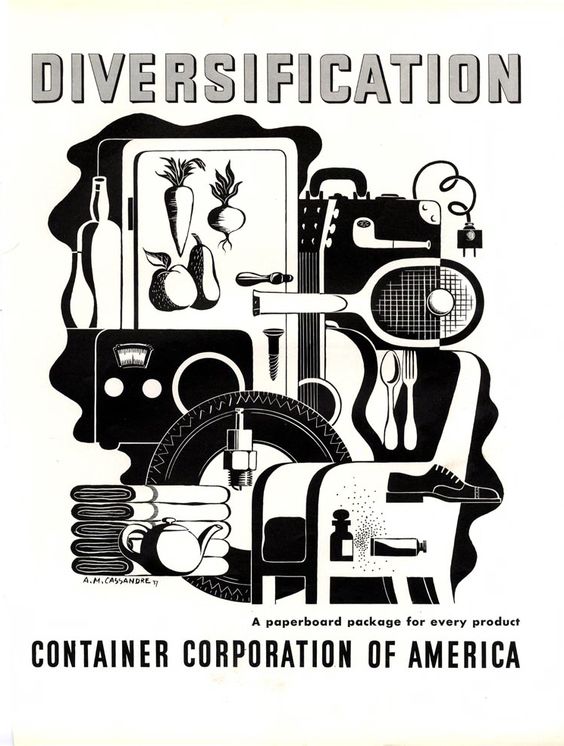

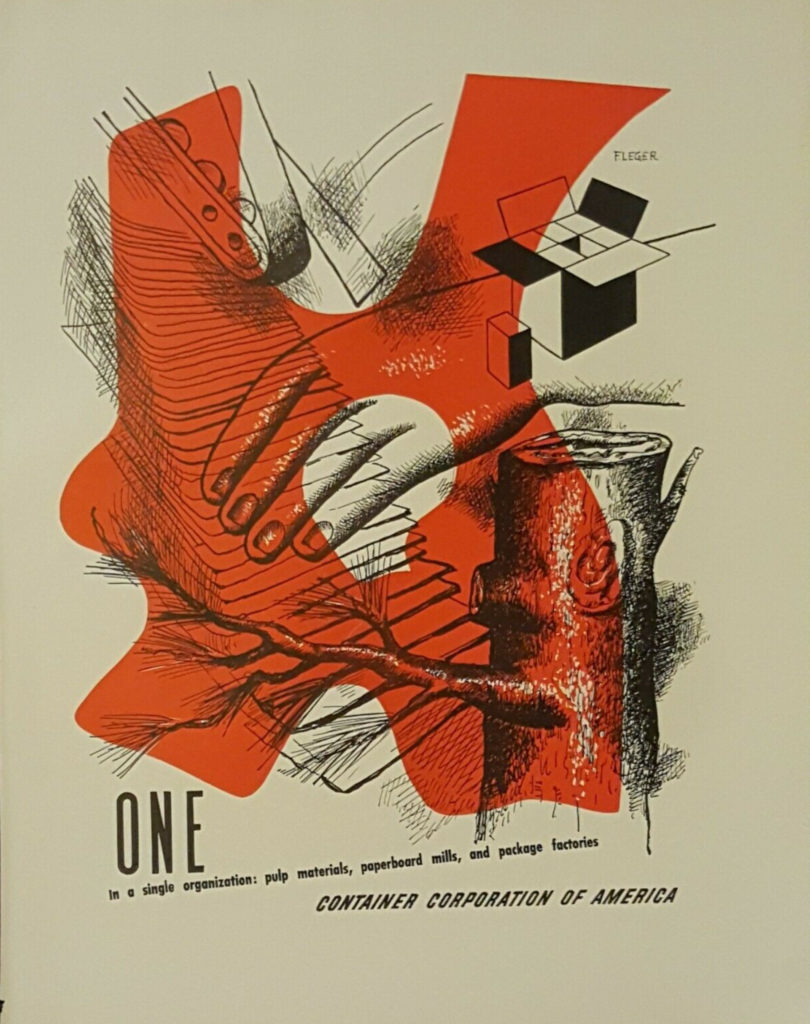

Led by Paepcke's CCA, packaging's cultural status blossomed, and became a vanguard enterprise, as Paepcke became embedded in Chicago's arts scene through the taste and sensibility of his wife Elizabeth, a former painter trained at the Art Institute, and the daughter of Professor William A. Nitze, chairman of the Department of Romance Languages at the University of Chicago. Paepcke quickly realized that product differentiation in a competitive industry — especially one whose main product was the lowly and largely invisible medium of cardboard — required not just packaging's power to sell, but the novelty of modern design to package what became known as "corporate identity." In 1935, he hired art director and color theorist Egbert Jacobson to serve as the CCA's first Director of the Department of Design, launching one of the most ambitious modernist makeovers of corporate culture in history (figure 5).24 From the look of the CCA's bank checks and annual reports, to the design of company trucks, office and factory interiors and furniture design, to its now legendary advertising campaigns featuring the work of artists like A.M. Cassandre, Fernand Léger, György Kepes, Herbert Matter, and Herbert Bayer, and others, Paepcke got modernism to push the paper, imbuing the soulless container with personality, while visualizing the terms of Container's managerial strategy.

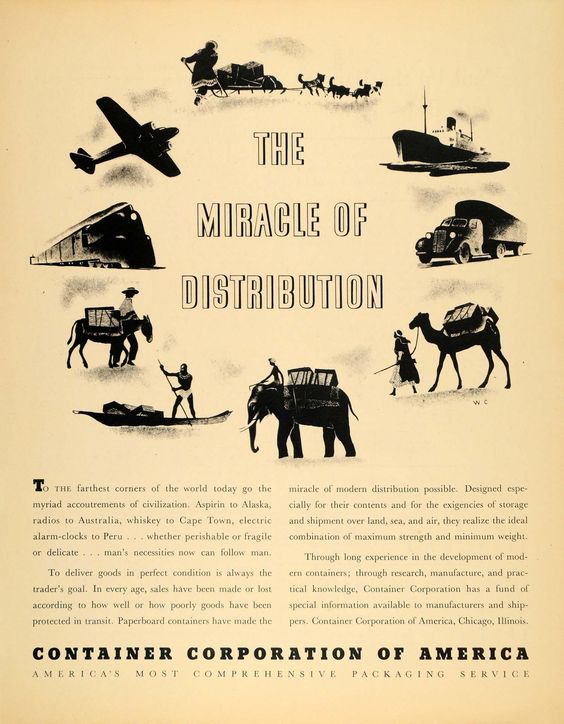

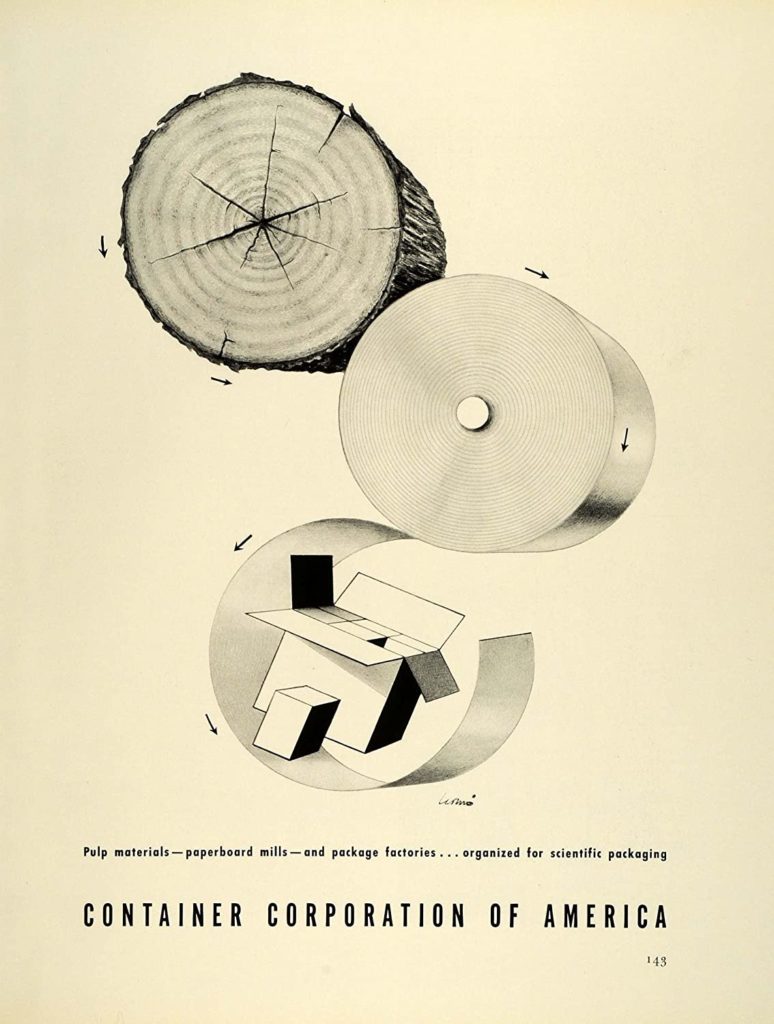

Cassandre's early ads, for example, extol the corporate virtues of "integration" and "diversification" (figure 6 and figure 7). Diversification meant not just the sheer variety of goods to be packaged in paperboard, but was also a defining characteristic of the firm's far-flung operations and geography, by 1941 "spreading out through twenty-two mills and box factories from New England to Texas."25 The former quality, the CCA's abiding "oneness" across the supply chain, Paepcke explained this way in an address to the Society of Security Analysts in 1945: "Most integrated unit in industry: sells containers, manufactures paper and straw board, produces its own sulphate pulp, collects waste paper, and delivers its finished containers with 300 units of its own trucks, tractors, and trailers."26 Legér depicts such integration through a bold chromatic superimposition of red that unites natural resource, human hand, and industrial manufacture (figure 8). Nature appears as a kind of giving tree whose branches have been lopped off to serve the giant hand hovering above it, and beyond that, the serial production of package factories, culminating in the final nested boxes of a CCA shipping carton. Here and elsewhere in the CCA's designs, boxes assume a reduced, abstract visual form — a volume devoid of texture or particularity. In this way, the carton aspires to a kind of geometric universality, and suggests the box's spatio-temporal ambition to be everywhere, to contain anything, in the extensive fashion of the modernist grid that it resembles.27 Like Legér, Kepes (figure 9) similarly draws on forms of graphic superimposition, here to promote scientific "technique" and knowledge in a photomontage. His design joins industrial machinery, its processed and nearly abstract product — a unfurled sheet of paper — and a grid charting, one assumes, the CCA's booming sales as the boxes of this integrated, diversified, technically expert firm make their way into the world through what a contemporaneous CCA ad dubs "The Miracle of Distribution" (figure 10). We see a similar logic in another ad (figure 11) that sources this miracle in the pulp materiality of resource extraction, an organized process rolling smoothy from tree to ream to a grid of nested boxes.

As these ads begin to suggest, the modernist packaging culture at Paepcke's CCA was an essential episode in the history of the very idea of corporate personality as an effect of good design. From the early 1950s to the 70s, when Container merged with Mobil Oil, before being sold to a St. Louis-based conglomerate in 1986, Patterson's films extended what CCA internal publications described as founder Paepcke's most visionary insight — that "packages are not just commodities; they are communications."28 Beginning in the mid 1930s, Paepcke's CCA championed modern "good design" as an important "function of management," and a means of providing the firm with a distinctive visual identity poised to intervene in a competitive attention economy and shape public attitudes and opinion. At the CCA, good design was a kind of meta-advertising. The company wasn't just selling boxes, but rather hawking the very idea of packaging as a communicative medium, and this required Container to model — in the refinement of its own corporate image — the branding power of an integrated design program. As Jacobson himself described his sweeping refashioning of the CCA's corporate image in 1950:

It has long been apparent that every graphic and visual expression of a company, designed or not designed, has an effect on its own employees and the public. When it is not designed, the impression is negligible, or scattered. Well-designed and integrated expressions not only make for strong original impacts, but are cumulative. The end result is good internal public relations.29

Writing in a special 1952 issue of the Berlin-based graphic design journal Gebrauchsgraphik devoted to Container's design program, the CCA's design consultant Herbert Bayer (with Maria Bergstrom, responsible for the interior and furniture design of CCA offices) extended his colleague's claims about "design as a function of management" by offering an analogy between the "visual elements" of "human personality" ("stature, physique, coloring, features and expression, and taste in dress") and the tactics of giving "a large corporation a personality that will favorably influence the people who work for it and those who buy from it."30 "Similarly," Bayer explains, "but on a vastly more complex scale, a large business corporation (which under American law is a corporate person) can create a personal impression through visual elements . . . The problem of management is to see that this visual personality is designed, in every detail, to produce the most favorable effects in all the company's dealings, internal and external."31

Paepcke's managerial vision at the CCA kept constant faith in the unassuming paperboard package as the bearer of something more abstract, ideal, and philosophical. "Corporate personality," an effect of good design, was one example. But his public speeches also position the paper box — as prosaic stuff, as material substrate — as part of a sweeping cultural and philosophical agenda at midcentury that unfolded alongside the wartime success and aggressive postwar corporate expansion of the CCA. Like the historian of technology Lewis Mumford, who once hailed the paper box's status as a revolutionary infrastructure of urban modernity, what he called "the swaddling clothes of our metropolitan civilization," Paepcke knew well his product's centrality in longer cultural and media history. 32 As he noted in his 1945 radio address "Broadened Horizons for American Business," without the paper-making industry, "science, education, and commerce could not have progressed as they have. Without paper . . . we would be without newspapers and magazines . . . large industries, such as advertising, printing, and publishing, would be without the essential medium for spreading the word."33 And he was keen to leverage the cultural saturation, communicative power, and civilization-making prestige of paper in his plan to redefine the ambitions and scope of moral responsibility of the postwar corporation.

Proudly adopting the ironic mantle bestowed upon him in the press — "a boxmaker interested in philosophy" — Paepcke used its structuring contradiction between the instrumental and the metaphysical, the banal and the significant, to chart a new terrain of corporate activity, with the box as the sign of a boundary-breaking interdisciplinarity. The businessman of the future, Paepcke noted, would have a stake in the production of the good life, rather than "the accumulation of material things and the pursuit of power." 34 Elsewhere he extolled that more meaningful, more capacious, more interesting life of "broadened horizons" as the domain of "lasting values — ideas, philosophy, culture," and "lasting happiness — creative work, enjoyment of art." 35 And he took pains to distinguish such immaterial, "lasting happiness" from mere capitalist accumulation or the pursuit of excessive, object-driven comfort. The future CCA manager, rather, would marshal his energies towards the "many extremely important unsolved problems in the fields of education, health and welfare, governmental philosophy, foreign and international policy, and cultural affairs." 36 And so Paepcke laid out the CCA's own "faltering and modest steps in directions which are not too commonly associated with the box business," including: the study of labor and industrial relations problems in coordination with the University of Chicago and other institutions; the CCA's involvement in various public and civil service endeavors and cultural organizations, including its curatorial argument for "the relationship between containers and modern art," as displayed in the Art Institute's "Modern Art in Advertising" exhibition in 1945; and finally, its "development in foreign lands through the establishment of mills and factories in Central and South America." 37

For Paepcke, these diversified cultural efforts exemplified a mode of integrative communication between too-rigidly specialized fields, professions, and disciplines, bringing philosophers and sociologists into dialogue with labor leaders; artists and designers into conversation with manufacturers; the "natives of foreign countries" into a "better and more friendly acquaintanceship . . . towards North American business." 38 Together, they are examples of "the fundamental idea of attempting to go beyond one's somewhat limited field." And while such boundary-breaking integration might stem from a philosophical inclination (what his friend Moholy called "relationship-seeing"), these "sincere and honest efforts to understand the thinking of groups, domestic or foreign, which are somewhat outside of one's own relationships," often "produce (quite as a by-product) material rewards which are as unexpected as they are delightful." 39 Like good design, in other words, Paepcke sensed that a philosophical, humanist commitment to the good life's "broadened horizons" of communication and understanding was also good for the bottom line.

A globally distributed communications medium, the paperboard container fueled a corporate-sponsored humanism at the CCA that conscripted modernist aesthetics to shape public opinion and ideas, and intervene on the terrain of value and ideology. As Paepcke explained in a 1951 speech at the University of Chicago's Annual Trustees' Dinner to the Faculty, U.S. citizens now had "the leadership of the world in laps," and material affluence, but were vexingly "without any appealing ideology around which other peoples of the world may rally."40 Summoning the propaganda savvy of the Nazis and the "more immediate" case of "Russia's communism" as examples of the galvanizing work of "bad ideologies . . . supported and understood by only a small percentage of their populations," he sourced the U.S.'s comparative ideological failures to the mutual distrust and failures of communication between the "four groups running our country: Government, Labor, Business, and Education."41 Here again, specialization breeds confusion over shared values that might be remedied by the cross-fertilization of ideas. "Ideologies lead people," Paepcke concluded, "not objects."42

Paepcke, we should add, was a self-professed "disciple" of his friend Mortimer J. Adler of the Institute for Philosophical Research, whom he had met through his contacts at the University of Chicago. Paepcke and his wife Elizabeth joined Adler and University of Chicago President Robert Maynard Hutchins's Great Books Club in 1943, and they recruited Adler to lead the Aspen Institute's summer seminars for the humanistic training of business executives in the 1950s and early 1960s. In 1958, in addition to his Great Books empire, Adler had published, with Louis Kelso, the The Capitalist Manifesto, a treatise written to combat what the authors saw as creeping socialism in the U.S., and to argue for the link between human happiness, undiluted capitalism, and liberal democracy.43 Paepcke promoted the book in his various speeches, and saw its "analysis of human freedom in all its important aspects, social, political, economic," as directly connected to his belief, following Denis de Rougemont, that "We are on the threshold of an era in which culture will be the most serious thing in life."44 Like Adler, Paepcke insisted on democratic society's need for "well-rounded," well-educated citizens — broad-minded people who would "not be purely specialists vocationally or technically trained."45

In Paepcke's postwar era, human beings longed to be free, but so too did cardboard boxes. Container culture was also containment culture.46 For a firm like the CCA, keen to expand its markets, liberal arts training prepared the ground for cardboard's postwar global distribution. The education of a democratic citizenry, Paepcke explained, constituted "the strongest bulwark of a free and enlightened society in which private enterprise can prosper."47 The boxmaker's lofty cultural ambitions would serve this philosophical agenda, one Paepcke saw as a specifically humanist one, demanding the kind of cutting-edge public relations efforts that made the CCA what Fortune magazine called cheekily "the glamour unit of the paperboard industry." 48

Paperboard, PR, and Propaganda from War to Postwar

Container culture was primarily logistical. The paperboard medium at its center was not just an unheralded and often invisible industrial product, but — as Patterson's films argue — an indispensable node in the broader sociotechnical systems constituting modernity. It matters, then, that Patterson came to filmmaking at the CCA after his work as a reconnaissance photographer. His films' logistical imagination extended into the postwar period a line of thinking about the paper box's location in global networks demanding coordinated, on-time delivery that matured during the CCA's wartime operations. With its business expected to soon hit "an estimated all-time peak of some $45 million," the firm became what a 1941 Fortune magazine feature called a "prime object lesson in the totality of total war." Paperboard consumption jumped during the conflict, what the feature dubs "a pre-packaged war," observing dryly, "even war comes in cartons now."49 By 1942, 30% of the CCA's business was war packaging, embedded in the military-technological conception of logistics as "the practical art of moving armies."50 If, as Jesse Le Cavalier has recently put it, "logistics transforms the space of warfare into one of technology and infrastructure," CCA's booming wartime operations and striking communication campaigns clarified the pivotal role of cardboard box within the technical infrastructure of global conflict, eventual Allied victory, and postwar reconstruction and the conquest of new markets.51

The firm's promotional booklet for this work, "Paperboard Goes to War" (figure 12), was designed by György Kepes, then leading the Light Workshop at Moholy's School of Design. The booklet extolled the "myriad necessities of this mechanical war" now being packed in paperboard: "a custom-built package for every product": from small arms ammunition (figure 14); to paperboard targets (figure 17), emergency rations, and tank and airplane parts (figure 16) — here nose cones for bombers. The modernist design of the CCA booklet continued in a robust advertising campaign, featuring a number of striking works by Herbert Bayer, including one (figure 17) with a gentle S-curve that links collected wastepaper to the serial production of cartons for bombs supplied and then dropped by an Allied bomber. The CCA's heralded efforts in recycling (the paperboard industry, Fortune reported, "lives over and over again on its own waste") now serve to exhort citizens to participate in efficient war production.52 Elsewhere, by graphically linking the internal grid of the standardized cardboard box with the pin-point distribution efficiency of military supply chains (figure 19 and figure 20), or the crosshairs of a target (figure 20), Kepes and Bayer positioned the CCA at the center of a logistically integrated global system (figure 21) with the box as its managerial heart (figure 13). In this fashion, the "Paperboard at War" campaign was a key example of the entanglement of the military sense of logistics as the "business of war preparation" and logistics as an emergent branch of managerial science overseeing the supply chain that encompasses the entire "'life span' of a product, from extraction of raw material to consumption and disposal by the end consumer."53

The campaign was visually arresting, but for the purposes of this essay, I am less interested in formal properties of these advertisements as exemplars of a modernist graphic design idiom than the broader wartime communications landscape they index, and in which designers in the CCA's employ and ambit — Bayer, Kepes, and Moholy-Nagy, especially — were embedded. For Paepcke, the "Paperboard at War Campaign," bringing good design into wartime mobilization, was a public relations coup, and an early instance of his desire to use design to craft what Lara Alison calls "a moral role for his company" in the postwar period, one forged in the thick of wartime morale-building and the efficient paperboard-bound provisioning and arming of U.S. military forces as a public service.54 As Paepcke explained in his address "Broadened Horizons for American Business," in May, 1945:

During these war years, the importance of the paper container has been brought sharply to the attention of everyone. At first, people thought of the paper industry as a nice little peace time business...But then, when the thousands of war products — munitions, gas masks, small arms, tank and bomber parts — rolled off the assembly lines, it suddenly became apparent that these vital items could not be shoveled into the hold of a vessel without protective packaging . . . When the war is won, it might be presumed that Container Corporation, having shed its more dramatic role, will relapse into a colorless peacetime routine. But this is not the future we envision for Container Corporation . . . There are in the world today many extremely important, unsolved problems in the fields of education, health and welfare, government philosophy, foreign and international policy, and cultural affairs.55

In anticipating the expanded social role of the progressive corporation in the postwar period, Paepcke was capitalizing on his firm's wartime success in conscripting aesthetic modernism into the business of paper packaging as a communications enterprise. This design program joined both senses of "communications" media: the older meaning of transport and linkage and the more familiar one of the transfer or transmission of information, here in the service of informing—that is, mediating—publics, audiences, and consumers.

As noted earlier, container culture expanded not just at the moment when the term "communications" emerged to describe the successful management of mass opinion, whether in politics or advertising (both arts of packaging, of course), but also as a nascent site of disciplinary knowledge—communication studies—fueled by the wartime study of propaganda.56 As a key player in this kind of knowledge production, the Humanities Division of Rockefeller Foundation, led by its Assistant Director John Marshall, sponsored the so-called "Communications Group" during the prelude to war. An important collaboration among the academy, the state, and private foundations, the Communications Group's explored the problems of "mass influence," the dynamics of fascist propaganda, and the possibility of "genuinely democratic propaganda."57 As I've argued elsewhere, Paepcke played a crucial role in brokering a relationship between the School of Design and Rockefeller Foundation bureaucrats during the war, especially in securing funding for film production at the School.58 Moholy's curricular aims for color film production at the School thus became entwined with a broader interest in funding educational film as part of a humanities mission at a moment of intense theoretical interest in the power of film and other mass media to build morale, to propagandize, and to shape public opinion.59 In this context, the intersecting wartime labors of Walter Paepcke's CCA, around the Paperboard Goes to War campaign, and Moholy and Kepes's design pedagogy at the School of Design make clear that "packaging"—as a design and management practice—expanded to mean more than the point-of-sale design of any given commodity's container. It encompassed the new profession of public relations, practices of propaganda then undergoing systematic social-scientific study, and the broader conceptual matrix of "communication" through with these managerial arts were understood.

For Moholy, wartime conditions pressed him to embrace and theorize a socially useful interdisciplinarity, but also what I've elsewhere called an "expanded administrative media practice," one that included course catalogues, syllabi, and the communicative value of 16mm Kodachrome films like Design Workshops, with which he travelled to promote the school. 60 These films worked as a promotional device, fundraising strategy, and a craft-based articulation of a vanguard humanities agenda. As a work of PR, deftly packaging the school's animating interdisciplinary and intermedial ethos, Design Workshops echoed Paepcke's own contemporaneous commitment at the CCA to color as a tool of corporate communication — a way of branding an organization's public identity through "institutional advertising" in a competitive media environment.61

Meanwhile, in the thick of the war, Moholy expanded the use of these color films and their imagined audiences as the School of Design underwent a significant curricular and administrative restructuring. To assuage anxious businessmen about the school's unorthodox organization and the politics of its curriculum, and to cultivate donors and sponsors, in April of 1944 Paepcke instituted a new Board of Directors comprised largely of industry leaders. In the process, the school was renamed the Institute of Design, and a campaign began for a new building. Moholy, as Paepcke framed it, would be freed to focus on his roles "(1) as an educator, (2) as a creative artist, (3) as an author, in order to spread your ideas of education, (4) as a lecture, and (5) as a general education administrator." 62 As Alain Findelli explains, this administrative reorganization, "supported by an energetic public relations policy," aimed "to conform with the new 'style' of management" more recognizable to workplaces of the potential donors themselves, and led to a more rationalized curriculum.63 In September, Moholy described to a CCA executive the "first orientation lecture with our colored motion picture," one aimed at enticing business executives from firms like Marshall Field's and United Airlines to enroll in the school's newly instituted evening lecture series.64 The gambit was a symptom of the School's restructuring, and one that extended the work of other CCA-sponsored programs in adult education like the "Fat Man's Great Books series" — a successful humanities seminar for Chicago business executives and their spouses, first convened in the fall of 1943 by Adler and Hutchins. The communicative value of color across the domains of art, cinema, and education, was also clear to Paepcke. An October letter to a colleague at the Chicago Association of Commerce describes this synergy around a recent Fernand Léger exhibition: "The Leger films, lecture, and exhibition were a great success — the large attendance and tremendous amount of publicity and four of Leger's paintings sold, on which the Institute, incidentally, gets a 10% commission."65 The letter also announced that one Donald Fairchild, a New York based public relations expert, had accepted the job of PR director at the ID, and he would soon be tasked by Paepcke with developing a detailed "publicity and propaganda campaign" for the school. By 1945, the two top salaries (by far) at the Institute were Moholy and Fairchild, at $6,000 each.66

The archival record also clarifies that the ID's two highest-paid employees were aware of each other's tech-savvy publicity and marketing skills, and may have understood themselves as competitors in the School's PR campaigns. In one letter, Fairchild described his disappointment at the "ineptitude" and amateur-ness of a local television broadcast to promote the ID. The program quality was especially galling for the ID, given "Moholy's early experience actually in television and with televisual affairs," and his awareness that "a new medium deserves a new visual presentation."67 Fairchild closes with a "word of the future" as chromatic prophecy: "black and white television is going to be shocked into its tomb by the advent of color unless they plan now to use it."68 Future PR for the Institute through color television, Fairchild seems to argue, would enact the cutting-edge approach to technology that should define the school's identity, as long-voiced in the proclamations of its visionary director and brand manager, Moholy, and as enacted in his Design Workshop films.

At the risk of turning Moholy into some brash Madison Avenue art director, it's worth pointing out that Moholy increasingly understood his work for the School within the parameters of a new vanguard communicative art of media messaging in a competitive attention economy, which also defined his sponsor Paepcke's approach to packaging. In a 1945 letter to Paepcke, Moholy lamented that, "in the last few months, we have very much lost contact with the press," and unfavorably compared Fairchild, the supposed PR "expert," to his predecessor.69 "The secret of the news release," Moholy explained, "is the constant flow of small items of interest, such as the special photography course for veterans, the work in occupational therapy, the American-Soviet architecture exhibit, and later the [James] Joyce and [T.S.] Eliot lectures."70 Keeping the far-flung work of the Institute constantly in the public eye, to a real expert, is no difficult task: "My experience shows that these matters can be accomplished simultaneously and the whole territory covered and contacts made personally until they become almost mechanical in their operation."71 Moholy's term "territory" here is telling, and a clear consequence of the wartime mobilization of the School of Design.72 As LeCavalier argues, territory is a key concept in the logistical imagination, comprising not just land "in the political-economic sense of use, appropriation, and possession attached to a place," but as the particular abstraction of terrain when "calculative tendencies" become dominant, and with them the techniques of measure, control, and prediction.73 What the interwar Moholy famously extolled as the technologically extended "New Vision" has now been reframed as a non-stop, quasi-automatic, logistical process of media manipulation, salesmanship, and the management of public opinion.

Moholy's early death from leukemia in 1946 meant that he wouldn't live to see his benefactor Paepcke's refinement of CCA's managerial strategies or the flourishing of the firm's moral and cultural ambitions in the postwar period — precisely the territory surveyed in some of Rhodes Patterson's films. He did, however, publish a posthumous treatise, Vision in Motion (1947) that assessed and, in many ways, enacted the commitment to canny public relations that he and Paepcke shared, even as it indicted the communications landscape in which the CCA sought to intervene in the postwar period. Written largely in 1944, Vision in Motion revised and updated Moholy's previous works of media theory — chiefly Painting, Photography, Film (1925, revised in 1927) and The New Vision: From Material to Architecture (1932) — while framing them within an account of his research "laboratory for a new education," the School of Design.74 As an experiment in what he calls "better visual communication," a challenge to the "conventional book form of previous generations," Vision in Motion was an object lesson in Moholy's paper-based promotional savvy.75 The book, published by Chicago's Paul Theobald and Company, included vanguard techniques of machine typesetting, the letterpress, and, to open its photography section, a richly illustrated discussion of color photography that included Moholy's paintings, his light-filtering experiments in Dufay Color, and various examples of "the controlled and fascinating work with colored light" at the ID, including colored light boxes.76 Notably, the book's experiment in "a functional fluidity and greater legibility, that is, a better communication," was also funded by the Rockefeller Foundation.77 Like Paepcke and Moholy, the Foundation's humanities mission was keenly aware of packaging as a matter of managing media and populations, publicity and propaganda, through better communication.

Moholy understood that the humanities mission of the School — its designs on the production of democratic postwar subject — had to advertise, which meant it had to compete with the corporate deployment of film, radio, and print media to propagandize and shape public opinion, and he took this up most directly in a section of Vision in Motion titled "The Propaganda Machine."78 Overlapping significantly with the thrust of Adorno and Horkheimer's contemporaneous "culture industry" thesis, an adjacent theory of corporate packaging, Moholy indicted unofficial education — "a widely organized advertising, publications, books, fairs, exhibitions, press and radio" — for fomenting an atmosphere of ideological mystification.79 For Moholy, unofficial education produces a media environment "of a thousand details, but missing all fundamental relationships." Without "the tools of integration, the individual is not able to relate all this casual and scattered information into a meaningful synthesis. He sees everything in clichés."80 As I've argued elsewhere, Vision in Motion sought to defend the role of the techno-savvy humanities themselves in redressing the ideological and biological impairments inflicted by corporate mass media and the seeming saturation of market values over democratic values.81 At Moholy's Institute of Design, the Light Workshop that housed the film and media program was framed within this broader regime of sensory and medial therapy, providing students with the "tools of integration." At the CCA, a similar project of humane integration would be pursued in Paepcke's various Aspen-based experiments in the humanities and humanistic communication, which extended the firm's managerial strategies and logistical imagination to explicitly cultural domains. In Aspen, however, the challenge would be to conceptualize the postwar liberal harmony of free markets and free people.

Container People and Corporate Humanism in Aspen

Like the wartime boxes, the CCA films organized and visualized flows of goods and information. But they also helped develop particularly humane kinds of postwar people — what the CCA called "container people." They would be cultivated through Paepcke's efforts to transform the moribund mining town of Aspen, Colorado into a thriving cultural and leisure destination, and a vanguard center of adult education. Paepcke's aim was to resuscitate an 18th-century bildungsideal — a belief in humane culture as a response to modernity's putative over-specialization, vocational training, and positivism.82

This therapeutic discourse, inspired in part by Moholy's desire for "integrated" postwar citizens, began with a twenty-day Goethe Bicentennial celebration in 1949, and led to a series of overlapping initiatives in global humanism: in 1950, the founding of the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies (AIHS), a summer program that aimed to unite the burgeoning general education movement spearheaded by Paepcke's friends Robert Maynard Hutchins and Mortimer Adler with the experimental pedagogical ethos of Black Mountain and Reed Colleges; in 1951, the Aspen Executives Program, a two-week summer program devoted to the "humane problems" facing midcentury corporate capitalism, and which aspired to train executives for their widened scope of responsibilities and domains of expertise in the postwar world; and The International Design Conference in Aspen, also launched in 1951, whose goal — as Egbert Jacobson put it — was to "establish once and for all the relation of design to business." And in 1952, Container Corporation produced a book that exemplified Paepcke's postwar efforts in humanistic world-making at Aspen: The World Geo-Graphic Atlas: A Composite of Man's Environment. Designed by Herbert Bayer, and given as a gift to CCA's clients, this limited-edition exercise in resource and data visualization aimed to map the changed political, social, and economic conditions of postwar world and the "shrunk distances" of "vastly improved communication and transportation facilities."83 Its maps of the world's cosmology, climates, populations, political structures, resources, and political economies — in roundwood, pulp, and newsprint — modeled methodologically CCA's belief in the humane integration of various domains of knowledge, and its commitment to "better understanding of other peoples and nations." Paepke's Aspen-based initiatives in corporate bildung were similar exercises: they sought to cultivate the integrated capacities of the postwar power elite and produce interdisciplinary knowledge as global human resource management.84

Here, we should pause to note the relationship between Paepcke's internationalist cultural and philosophical ambitions at Aspen and the aggressive global expansion of Container, which began during the war. In 1944, Container established its International Division, "incorporating Carton Internacional, S.A., Panama; formed Cartón de Columbia, S.A, with 50% interest, and acquired partial interest in two Mexican firms, Cartonvases de Mexico, S.A., and Industrias de Carton, S.A."85 As Paepcke explained it, this was the natural outgrowth of the CCA's commitment to diversification, both "productwise and geographical," with factories and mills from "Boston to Florida, Chicago to Texas, also Mexico and Colombia."86 In 1954, it expanded its Latin American operations, acquiring three Venezuelan companies: Corrugadora de Caroton, S.A., Cartón de Venezuela, and Union Gráfica. In his corporate history of the CCA, John Massey, who served as Container's third Director of Design from 1964 until the Mobil takeover in 1983, explained this as part of Container's "philosophy" of not expanding in developed countries, but rather to "bring CCA's management abilities, outstanding packaging technology, and marketing know-how to developing countries, where the company could provide assets not available locally. Then, as the economies of those countries developed, their need for paperboard packaging would grow in a geometric progression, with potential for good profit."87 Aggressive corporate expansion through foreign direct investment is one materialization of the knowledge-sharing across boundaries that Paepcke had extolled at the dawn of the postwar. His Aspen initiatives would be another.

In 1955, the CCA revised this philosophy of prioritizing "underdeveloped" nations, forming Europa Carton, A.G., with a corporate HQ and carton plant in Hamburg and a container plant in Dusseldorf. Coverage of this European expansion in Business International explained Germany's rapid adoption of "U.S. merchandising methods, from prepackaging of foods to supermarkets," as part of its own postwar economic recovery, allowing Container to "cash in on sales trends and upp[ing] buying power in Germany."88 A Der Spiegel piece from 1958 cast Europa Carton's emergence more skeptically as "the latest sign of American capital infiltration," quoting Paepcke that the factory was built "just in time for the common market in Europe," and noting West German industrialists fears of American competition.89 In the same year, Paepcke gave a speech defending Container's practice of foreign development, noting the "lack" of capital, know-now, integration, merchandising, design laboratories, and general organizational failings characterizing the CCA's foreign competition, and arguing for the tremendous opportunities for research and profit for firms like his own. "POSSIBILITIES ENORMOUS," he observed: "Germany from nothing two years ago to $20,000,000 sales rate by Fall of this year."90 Such diversification, he noted, is also an "excellent hedge in case of temporary recession or depression in the U.S.A." He did, however, observe some "headaches" in his otherwise rosy picture of untrammeled growth for the packaging industry: "Revolution-Venezuela. Devaluation-Colombia." But, he assured his corporate audience "You are well-paid . . . You can afford them."91

The version of systematized knowledge production offered in Patterson's The Packaging System (1961) follows on the heels of the CCA's accelerated global expansion in the 1950s, or what Paepcke called its "hard, courageous, imaginative work." Its stock split 4/1 in 1956, with sales of $276 million and profits of $18.2 million, and it acquired Cartón y Papel in Mexico in 1957 and its boxboard and containerboard mills. In 1958, it completed a new corrugated plant in Bogotá, Colombia; five new properties in Germany (Viersen, Augsburg, Hamburg, Bremen, and Lubbecke); and additional properties in Soest, Holland, and Mexico City. In 1959, Cartón International had acquired the Italian firm Vosa, S.p.A., and the "first commercial processing of tropical hardwoods for pulp in Cali, Colombia."92 And in 1961, it built a corrugated plant in Medellin, Colombia." In this context, The Packaging System — like Bayer's World Geo-Graphic Atlas — can be read as a minor chronicle of midcentury globalization, and an effort to visualize the logistical complexity of the CCA's optimization of distribution, from global resource extraction, through industrial processing, packaging, and consumption.

In doing so, the film implicates itself, as a corporate communication, in the firm's broader commitment to the smooth, frictionless flow of packages and of information. Patterson's narration stresses the strategic location of the CCA's various paperboard mills near their sites of natural resource extraction, and details transportation networks as part of the "speed and efficiency of product distribution," much like the automated packaging machinery also sold by the CCA. But the film also insists on the swift circulation of information within the "comprehensive testing" undertaken at its various research and development centers, and beyond, to audiences inside and outside the firm. In one sequence (clip 2), we see how uniformity of quality control at the CCA's then-26 domestic plants is secured through the "companywide circulation of information and data" compiled by the Container Division Laboratory — information "supplemented" by internally generated "reports on all significant structural and merchandising developments," and then "augmented" by frequent coverage in the trade press, both domestic and foreign." Patterson's editing in the sequence joins the containers' status as communications media — substrates for printing, subject to careful testing in CCA labs — to a larger network of information circulating both inside the organization in typewritten memoranda and reports, and beyond, in the pages of trade periodicals around the world.

A related sequence devoted to the work of knowledge production in the CCA's laboratories and its global circulation worldwide demonstrates the tight relationship between a film like Patterson's The Packaging System and other internally circulating CCA communications, especially its annual reports, whose rhetorical work the film doubles in parts. As the narration stresses the exchange of information offered by the firm's "completely integrated facilities, encompassing some 72 domestic and 52 foreign establishments," Patterson superimposes a shot of lab researchers onto a map of North America, and we zoom out to a hemispheric view, before dissolving to a map of Europe — a nifty cartography of the CCA's booming packaging empire, circa 1963 (clip 3). The graphics in this sequence (figure 23), and throughout the film, echo the visual idiom of the contemporaneous annual reports, produced by the Design Department and a central feature of the CCA's design program since the mid 1930s. The 1960 annual report (figure 24), for example, deploys the same two maps, but stacks them on the recto of the page.93 This visual idiom is notably free of topographical detail, in keeping with a modernist grammar indebted, like Bayer's Atlas, to the rationalism of Otto Neurath's isotypes, and to a pervasive postwar visual language of abstraction among wartime planners.94 Endowed with "the power of erasure, the ability to sweep out the old and usher in new modes of communication and behavior," such pictorial abstraction often worked to conceal "planning's most violent aspects."95 The aim of the spread, again, is to visualize "integration," here done in a graphic echo in which the maps' twin circles appear as expansions of the first, smaller circle on the verso — a cross-section of an enormous roll of paper that itself echoes the tree from which it originated.96 These three circles are graphically integrated by a thick tan line (the hue of cardboard, of course, central to the CCA's early branding from jump) whose color is picked up in all the smaller circles representing CCA facilities now dotting the globe. The dots indicating the diversified distribution of CCA facilities recall the nodal patterns of lines and dots crossing the globe in the "Paperboard at War" imagery, where the site of plant or mill seems to occupy less a particular place than an abstract, territorial position — one that, during the war, would have been the site of coordinated, tactical military provisioning. The play with integrated circles (here, tree and globe) echoes an interwar CCA print advertisement (figure 11) depicting the organized flow between a cross-section of a tree trunk, a massive ream of processed paper, and the final shipping carton, a compact visual allegory of resource extraction and commodification through "scientific packaging." It's not just an abstract modernist image of a cardboard box. Rather, it's an image of containerization as abstraction, as universalization, as capitalist globalization.

Related graphic designs that picture scenarios of optimal, integrated "flow" appear in all of the contemporaneous annual reports. Two additional abstract views of logistical "integration" appear in the 1956 report (figure 25). In one, the eye moves from raw materials, to mills and processing plants, to products (whose uses again appear in a list) through two graphically superimposed waveforms that smoothly expand and contract along the supply chain, focusing our attention again on a list of the CCA's diverse locations. In another (figure 26) the focus is on the role of the Design Laboratory itself in two integrated, symmetrically flowing processes: "Making Shipping Containers" and "Making Folding Cartons." These rhymes between the visual language of Patterson's film, print ads (figure 27), and the contemporaneous annual reports themselves exemplify the CCA's integrated design program, also detailed in The Packaging System, and its centrality is signaled in the Design Department's placement in the center of the cardboard box that provides the film's basic structural conceit.

Figure 26. Container Corporation of America Annual Report, 1956. Designer: Likely Edward McKnight Kauffer. "Making Shipping Containers. Making Folding Cartons." Walter P. Paepcke. Papers, box 24, folder 1, Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library.

Figure 27. "One Integrated Flow of Production," Edward McKnight Kauffer, 1941.

The sequence on design (clip 4) is appropriately detailed, given the firm's corporate identity, and design's larger integrative function in the frictionless rhythm of the CCA's supply chain. It begins with a soft-focus shot of a city street at night, with streetlights, headlights, and electric signs turned into abstract dots of color. This is likely an homage to the similar opening of Moholy's own experimental film about the School of Design, Do Not Disturb (1944), and another, more extended study of the play of electric lights, Night Driving (1957), by Patterson's friends and fellow designer-filmmakers Morton and Millie Goldsholl, who were students of Moholy at the ID, and shared his fascination with light manipulation.97 The frenetic scene comes into focus to illustrate "the growing diversity and quantity of products competing for the consumer's interest," and the city's dynamism — as a competitive attention economy — is then superimposed with a kaleidoscopic image of various products and their package design. We are swiftly introduced to the need for any given package's work in communicating "visual appeal," and thus, to the role of graphic design as a process comprising color, typography, illustration, design form, texture, and trademark — all elements deftly assembled by the "creative intuition of the artist." The work of Albert Kner's Design Laboratory — creating "individuality and uniqueness and utility" in every product — is dispersed in various CCA locations, domestic and foreign, using "all of the resources of graphic design," especially color, as systematized in the CCA's Color Harmony Manual, and used by "business, industrial, and educational organizations throughout the world."98

Design at CCA is cast as a creative art here, but also an empirically verifiable practice and a quasi-behaviorist, logistical science indebted to cutting-edge market research. In the "Design" segment, Patterson offers examples of Design Laboratory instruments for "objectively" evaluating and testing a package design's legibility; he stresses the extension of package design into the creation of point-of-sale displays (counter displays, floor stands, spectaculars); and he marvels at the extensive files of research drawn on for comprehensive customer presentations, which involves slides and moving images. But he also insists in a later segment on the need to direct high production to a "predictably high consumption," and thus the CCA's insistence on the integration of design with marketing, devoted to "measuring and predicting consumer response." The purview of the Design Laboratory thus extends into the social-scientific work of dealer and distributor interviews, design and advertising analyses, and two further sub-divisions of the firm's knowledge work: the Consumer Research Department in Park Forest, Illinois, which conducts responsible statistical sampling of consumer behavior; and the "strategic" development of new markets and their support, conducted at the Valley Forge Marketing and Research Center.

To get a sense of how forward-thinking CCA's Department of Design actually was, consider that management theorist Peter Drucker, writing in 1962, described distribution as "one of the most sadly neglected, and most promising strands of American business," and he anticipated a new breed of manager trained to think systemically, to "see operations in a comprehensive way."99 Producing precisely that kind of systems orientation, of course, is part of the philosophical and ideological work of a film like The Packaging System, and beyond it, of the IDCA. Because logistics is preoccupied with the coordination of an object's location in space and time, in the context of retail, logistics concerns "what to stock and where to direct it," which depends on understanding and predicting consumer habits.100 This link "between distribution and desire," LeCavalier explains, was evident in "early explications of the logistics industry" in the late 1960s, and was the clear preoccupation of both the CCA's Design Laboratory and the range of interdisciplinary experts convened contemporaneously at the IDCA in the late 1950s and early 1960s.101

In many ways, in fact, The Packaging System's approach to the CCA's Design Laboratory as part of an integrated design program working across the familiar disciplinary boundaries of the arts, the sciences, and the social sciences was a function of the precisely the kind of training in humane interdisciplinary communication essential to the knowledge work of midcentury design conferences like the IDCA.102 Even as Patterson was making films like The Packaging System, he was on the ground in Aspen, producing filmed chronicles of Container's efforts to develop the just the kinds of people whose capacities to comprehend, visualize, and logistically manage the world might rival Bayer's own. As I've argued elsewhere, the IDCA was perhaps Paepcke's most successful platform for understanding those managerial duties, and it emerged at a moment of heightened scrutiny to the very form and technique of the conference itself as a mode of multi-modal, quasi-therapeutic global communication.103 International and interdisciplinary, midcentury conferences like the IDCA became — for designers and the far-flung retinue of experts that gathered yearly at Aspen — a crucial site for conceptualizing the global reach and scale of postwar media of mass communications, and for grappling with the ethical responsibilities for managing those media, shared by designers and the corporations whose identities they helped to define. Reckoning with the challenges of a postwar liberal order over with the designer would now preside, conferees conceptualized film as they came to grips with the broader role of communication — its media, its technologies, its global infrastructures — in organizing and administering the future of that world. At postwar design conferences like the IDCA, a kind of industrial common sense was forged, and eventually contested, regarding film and moving-image technologies as instruments of logistical organization, as strategies of humane world-making, as compensation for the seeming unnatural or dissensual worlds of postwar life.

Rhodes Patterson was well aware of the IDCA's high-minded ambitions. In an admiring profile of the Chicago-based designers Morton and Millie Goldsholl, who played essential roles in the pivotal 1959 IDCA meeting, Communication: The Image Speaks, Patterson linked their "philosophically oriented" practice to the heady environment of the IDCA. In his sponsored film IDCA: The First Decade (1961), Patterson articulates the relationship between Container's humanist designs on global culture in the postwar period and its logistical imagination (clip 5). Taking stock of the IDCA's inaugural decade, Patterson's twenty-minute film works to record the operations of the institution and promote the IDCA to potential attendees. IDCA captures a key moment in the consolidation of the conference, memorializing its institutional emergence, reifying its organization, and promoting the significance of its future iterations for what the film's voiceover calls "our total culture" — a telling phrase. In commemorating the conference's first decade, the film also works as a kind of memorial to the global cultural ambitions of its founder, Paepcke, who died in 1960.

Packaging the IDCA's conceptual work to potential attendees, the film is a kind of industrial "process" film, only what it documents is not the fabrication and function of a product or commodity, but the making of the conference as a space of postwar knowledge production, spawned from Paepcke's inspired conception. Recall this graphic from The Packaging System: it is an image not just of supply-chain integration, but interdisciplinary knowledge production modelled by Bayer's World Geo-Graphic Atlas and the knowledge work of the IDCA itself, comprised of design heavyweights, artists, educators, corporate executives, and scholars from a diverse range of disciplines (figure 5 and figure 28). Built of the fruits of the conferees' immaterial labor — panels, speeches, keynotes, seminars — Patterson's film underscores and extends the circuits of communication that organize Aspen as a "creatively oriented conclave."

The bulk of the film is comprised of highlights from the first decade of the conference proceedings, re-assembled through Patterson's editing, and organized by a voiceover. After a micro-history of the development of Aspen, and some "starkly statistical data" on the range of conference topics over the first ten years, the voiceover asks, "But what is IDCA really like? What makes it go?" The narration then adduces archival footage and audio from past talks as attempts to provide "something of the scope" of the wide-ranging discourse, while "minimizing any detriments to the original communication." Narratively, the film draws on the conventions of travelogue and ethnography to entice potential future attendees, introducing spectators both to the breathtaking natural beauties of Aspen as a location (Patterson's camera observes "some of the places you will pass through on your way to Aspen") and to the particular routines and sites of IDCA activities. Ten years in, it seems, these have coalesced into a quasi-ritualistic form: the movement from centralized morning sessions to decentralized afternoon seminars; the poolside evening parties at the Hotel Jerome; the scheduled "unscheduled" Wednesdays, which allow attendees to "pursue happiness" through Aspen's abundant leisure activities (hiking, skiing); Friday's "final assault" on the central topic by all keynote speakers, and the concluding summary address.

Structured according to the IDCA's typical five-day conference schedule, and describing its daily and weekly organization, Patterson's film is what I've called a "meta-communicative work."104 It talkily documents the organization and planning of an institution whose product is communication itself — discourse the film assembles as representative, and whose clarity the film enacts. The film underscores the circuits and surfeit of communication that sustains, and thus organizes, Aspen as a node of high-altitude knowledge work, stressing that even the seemingly extra-curricular conference moments — impromptu poolside chats — are "sites of significant conversation." As a meta-communicative film, IDCA links the creative, humane, interdisciplinary thinking and communication in Aspen to the film's own functioning within the CCA's expansive global network of corporate speech, and the talky packages at its core. Like many industrial films, Patterson's should be understood not in isolation, as some archival oddity, but as exemplary of the CCA's way of thinking film itself: as a "communicative" medium, a mode of organization, and thus, a technology of postwar management.105 His CCA films join the very characteristics of humane, creative, corporate personhood developed in Aspen to the familiar attributes of the cardboard boxes and their own systemic functioning — integrated, flexible, responsible, the product of various regimes of expertise, and always communicative.

In 1961, in fact, Patterson was not just chronicling the IDCA's interdisciplinary conversations, but actively greasing the wheels of communication as an invited seminar leader and exemplary "creative." That year's theme was "Man the Problem Solver," and we can get a sense of the typically idiosyncratic assemblage of expertise at the conference in its Cycle 2 (of three), devoted to "creativity" and problem solving from practitioners in the arts and sciences. Creativity, of course, was a crucial Cold War habit of mind, connected to the virtues of interdisciplinarity itself, and connoting a basically democratic openmindedness and nonconformity. It was an essential quality of the kinds of broad-minded, flexible container people that the CCA saw as essential to the spread of liberal democracy worldwide, and the kinds of enlightened, expansively thinking managers he sought to attract to the IDCA and the AIHS.106 Moderated by Paepcke's recently widowed wife, Elizabeth, Cycle 2's panel of creatives featured Professor Tomás Maldonado, design theorist and then rector of the Ulm School of Design in Germany, who delivered a highly technical paper on defining an objective methodology for problem-solving in the training of industrial designer; Peter C. Kronfeld, a physician at the University of Illinois who spoke on "problem solving in opthomology,"; Richard Pick, a musician; and the Chicago-based writer and Pulitzer Prize winner Gwendolyn Brooks, who read a number of her poems, including work for A Street in Bronzeville (1945) and Annie Allen (1949). That cycle's interlocutor was Bruce Mackenzie, a science writer and editor for IBM. Patterson served as seminar leader for Cycle 3's papers, devoted to the "business of problem solving, today and tomorrow," and featuring the Russian-born science photographer and microcinematographer Roman Vishniac, as well as Edward C. Bursk, management theorist and editor of the Harvard Business Review.107 Later that year, Patterson would edit another CCA film, Top Management's Expanded Role in Marketing (1961), which chronicled a CCA-sponsored symposium in New York on the rising centrality of marketing, at which Bursk was a featured panelist. Many of the claims made by the symposium panelists — about now being "in the business of creating customers," not just products; about the need for marketing as a response to the "constant change and growing complexity of our time"; about marketing's "flexible" integration into the various operations of the firm; about marketing science's relationship to "moral" considerations; about the need for a firm to have leadership from which emanates a "philosophy" or attitude that defines the organization — found their way, in some fashion, into the rhetoric of The Packaging System.108 And they were also just the kinds of questions being regularly pursued at the IDCA, as designers, artists, politicians, educators, and social scientists alike grappled with their shared managerial responsibilities in an often-vexing culture of abundance. This also meant awareness of their responsibility for the values of a shared world culture transformed by the explosive growth of technoscience, knowledge production, and rapid technological change. In sum, the logistical imagination on display in a seemingly modest CCA film like The Packaging System, was, like its director, fully steeped in the conceptual and philosophical approaches to the organizational challenges of a postwar liberal world order. In it, designer-filmmakers like Patterson played a crucial role in dictating the shape of the democratic good life and asserting the more intangible, immaterial values of container culture.

Logistical Humanism: Or, Great Ideas

In a publication celebrating its 50th anniversary in 1976, the CCA extolled its longstanding managerial emphasis on ideas rather than things; it insisted that the service it sells is "first the creation of new packaging ideas, and secondarily the physical package itself which embodied the multifaceted concepts of the product."109 This, of course, is an extension of the basic dialectic between the concrete and the abstract that, I've argued above, defined Paepcke's approach to container culture. In the annals of the CCA, these values were best exemplified by its most famous and longest-running ad campaign, The Great Ideas of Western Man, in which famous artists offered visual interpretations of "great ideas," quotations identified and indexed by Adler himself, then a paid CCA consultant largely responsible for the version of liberal humanism taught in the Aspen Executives program. Running from 1950 to 1980, the CCA's Great Ideas series, as John Massey later explained, was an "integral part of the communications matrix, and it became more than an advertising program," seeking to embed Container's public relations strategy deep in the philosophical and aesthetic marrow of the Western tradition.110

Adler's Aristotelian and Thomistic humanism was also administrative and logistical in orientation. It hinged on providing the just-in-time conceptual equipment necessary for the spread of liberal-capitalist democracy worldwide. As Reinhold Martin has argued, the Great Books program was abetted by the ur-bureaucratic form of the reading list, which Adler, like John Erskine before him, intended as a reaction to the "laissez-faire system of elective courses," and was nurtured by the "administrative imagination that guided Erskine's activities during the war."111 The hugely successful Great Books reading groups — local seminars around the U.S. totaled 1,176 by 1953 — were followed by the 1952 publication of Hutchins and Adler's Great Books of the Western World series at Encyclopedia Britannica, a 54-volume collection, published in conjunction with the University of Chicago in 1953; and then by a two-volume guide to the Great Books set, titled Great Ideas: The Syntopicon of Great Books of the Western World. For Adler, Martin explains, the great books were "more than a list; they were a system," more a "logistical" procedure than a hermeneutic enterprise.112 This, Adler's own packaging system, was united by the Syntopicon's "organizing matrix" of 102 "great ideas," from "Angel" to "World," and those ideas were then cross-referenced across the whole of the collection in an extensive index compiled by a staff of clerks.

Martin adduces the Great Books system as an example of the bureaucratization and commercialization of knowledge inherent in the discourse of the university as an organizational form. We should not balk at this characterization, since universities, as Mark Garrett Cooper and John Marx have recently reminded us, "were corporations under the law before businesses were," and hand-wringing about the businesslike traits of universities is at least as old as Thorstein Veblen, not a more recent symptom of "the university in ruins," or contemporary neoliberalism.113 Moreover, the cases of Erskine and Adler, as well as Moholy and Paepcke, remind us that the real business and social function of schools and universities is the work of "audience creation and management."114 Institutions of higher education like Moholy's Institute of Design or Erskine's Columbia existed in a competitive media environment, vying for the attention for audiences that have to be produced, then managed and transformed through different techniques of address and mediation. This, Marx and Cooper show, was evident in the co-evolution of the profession of public relations — born from wartime propaganda efforts — and a host of media-savvy university strategies of packaging and promotion in the 1920s and 30s, which included the road shows of Great Books advocates, and later, Great Books as a bona fide humanities PR coup and logistically distributed multi-media brand.115