Issue 6: Midcentury Design Cultures

On the morning of November 30, 2015, observant Parisian commuters — yawning at bus stops, crowding onto subway platforms, or walking to their local cafes — could hardly have missed an unusual advertising campaign. World leaders and negotiators had assembled in the city for the first day of the United Nations Climate Change Conference, better known as COP21. Many attendees and observers hoped for a plan to keep global warming below 2ºC , but outside the convention hall, activists were skeptical. The previous evening, the guerrilla art group Brandalism had appropriated some 600 JC Decaux ad spaces around the French capital to highlight causes for concern. In place of glossy advertisements for cosmetics, handbags, and sportscars, the group had placed satirical posters deriding the environmental damage inflicted by COP21's very sponsors, including France's largest oil company, Total. In one poster, a smiling helicopter pilot points to an offshore oil rig behind text reading: "Our philosophy: you don't need to know." Another, by the American art collective Not An Alternative, features a drawing of an ornately-framed oil refinery and the message: "Dear Louvre Museum, / When Total & Eni sponsor you, / You Sponsor Total & Eni." A few days later at the Louvre, artist-activists poured a viscous black liquid in the museum's white marble lobby and circled it barefoot, widening the stain until police arrived. Up above, another group, posing in front of I.M. Pei's iconic glass pyramid, opened black umbrellas with white letters calling for "Fossil Free Culture" (figure 1).

Similar protests have become a familiar sight at western art institutions, which have increasingly faced criticism from groups such as Liberate Tate and Art Not Oil for supporting and profiting from what one recent book terms big oil's "artwash."1 These groups represent an important element of recent challenges to art patronage that have received wide publicity, such as artist Nan Goldin's challenge to the art-world influence of the opioid-enriched Sackler family.2 But they should also be understood as part of the broader oil and gas divestment movements and activist efforts either to challenge the petroleum industry directly or to use the threat of fossil-fuel blockage as a lever for other political aims. In France, the latter strategy played a small role, for instance, in the resistance to Emmanuel Macron's proposed changes to France's pension system, which included limited refinery shutdowns in January 2020 aimed at reproducing the fuel shortages seen in 2010 when protestors likewise used refinery strikes to resist Nicolas Sarkozy's pension reforms. Similar blockades were also a less-publicized feature of the "gilets jaunes" protests that emerged in November 2018, in part as a response to a hike in the nation's gas tax that pinched the already shrinking pocketbooks of automobile-reliant suburban workers. Their plight, as I will discuss in the conclusion, highlights one of the failures of the design vision created in France during the 1950s and variously sold and challenged by the images and artworks discussed in what follows.3

The struggle over oil and its culture — one so often played out at the juncture of symbols and materials — is this essay's concern.4 Recent activist art performances like those staged during COP21 have called attention to contemporary entanglements of art and oil, but this essay seeks their roots elsewhere. Tracking back to oil's midcentury ascendancy, it examines how petroleum interests, recognizing the utility of aesthetic power, turned to art not simply as a site for investment or what is now called "greenwashing," but also as a means to articulate a vision for an oil-powered future and to teach liberal democratic subjects to embrace and enact it. As scholars in the interdisciplinary subfield devoted to "petrocultures" have demonstrated, culture has long played a significant role in mediating oil's steady entry into daily life. Among this field's important arguments is that popular culture has both naturalized and glamorized petroleum, often by foregrounding the things it makes possible — forms of life for an era of cheap energy — while downplaying the stuff itself. Writing about the American context, for instance, Stephanie LeMenager calls one such form of life, with its "now ordinary U.S. landscape of highways, low-density suburbs, strip malls, fast food and gasoline service islands, and shopping centers ringed by parking lots or parking towers," a "petrotopia."5 Americans learned to embrace that topos, LeMenager and others have argued, through various forms of popular culture, from mass-market fiction and Hollywood films to Disneyland.6

French popular culture developed its own "petrotopian" visions alongside more ambivalent responses to oil's steady incursion into French life and public space. Perhaps no French film of the 1960s better embodies the latter approach than Jacques Demy's Les Parapluies de Cherbourg (1964), the intricate design of which includes a key emblem of crude styling: an Esso station. Introduced both subtly, in the form of a toy model and Guy's place of work, and then eventually as his own clean-lined, brightly illuminated modernist business, the service station becomes the child's (and France's) quietly nightmarish dream fulfilled (figure 2). But while I will return to Demy and French feature films briefly below, here I wish to draw greater attention to the important cultural work produced by the petroleum industry itself.7 While popular culture no doubt helped frame oil's vernacular meaning, petroleum producers, in France as elsewhere, recognized the strategic value of using culture to control their product's perceived significance and future value. I focus on the 1960s, when oil first became the world's leading energy source. During the previous decade, as new discoveries in the metropole and across France's fading colonial empire allowed French petroleum producers to compete with traditional coal power and the upstart nuclear program, visual culture became an important venue for a struggle for literal and metaphorical power over France's energy future. In print advertisements, corporate magazines, and industrial films and photographs, French oil companies sold an oil-centric design vision in which their industry appeared as an efficient system of resource management reaching out across the globe to connect wells to refineries and refineries to petrol stations. This vision offered readers and viewers what this essay will describe, with particular attention to a series of advertisements released in the summer of 1965, as early crude designs for an oil-built world.

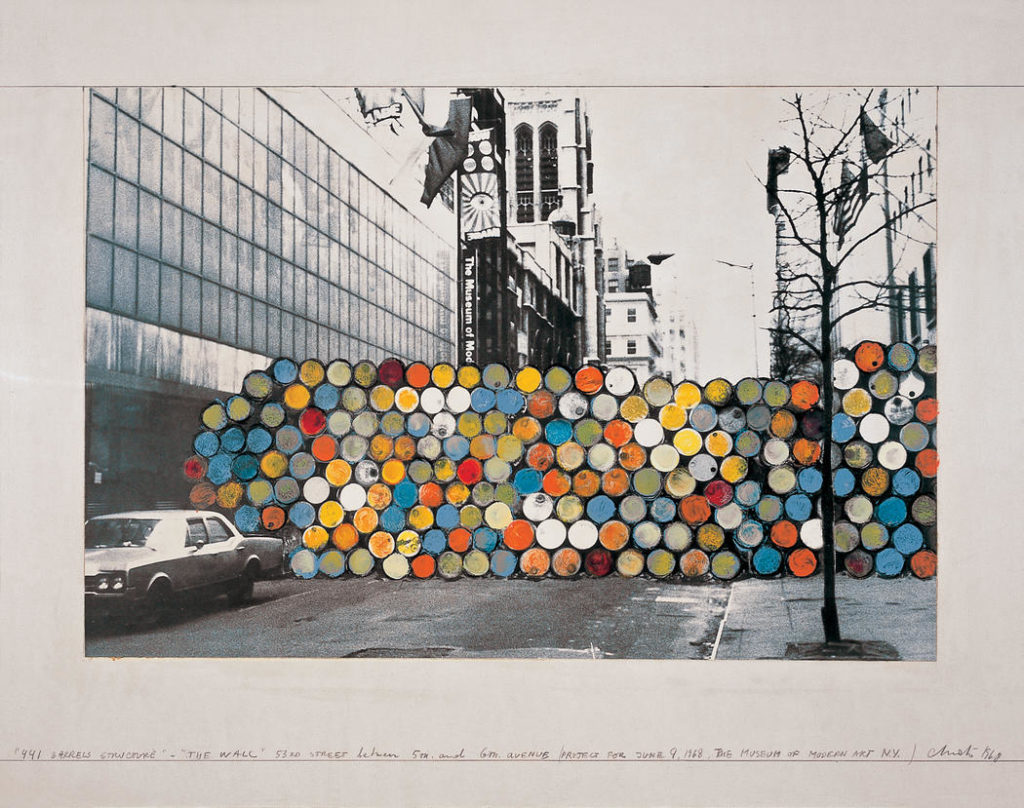

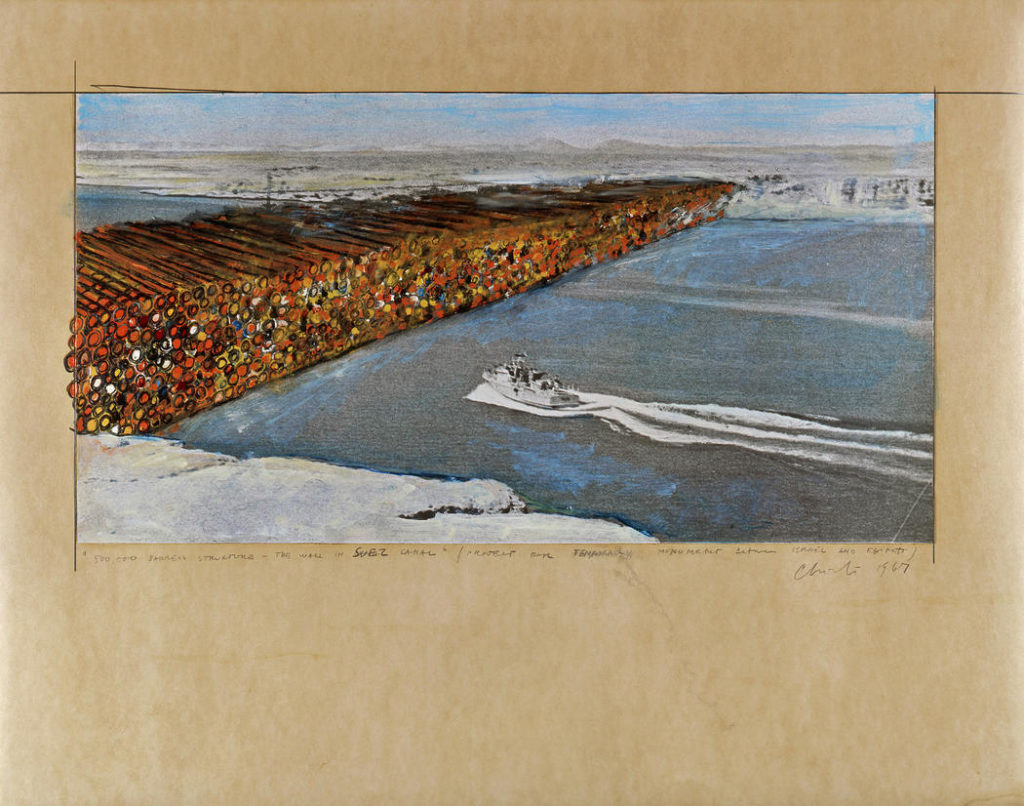

Neither that vision, nor the normalizing work of popular culture, went uncontested. Like today's Louvre protesters and Brandalists, artists in the 1950s and '60s challenged this system by exploiting its material supports. In the second part of the essay, I turn to one set of evocative examples: the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, the artist couple most famous for their large-scale wrapping projects but who also used oil barrels to articulate a vision of the petroleum industry that was fundamentally at odds with the one being sold by its proponents. In a series of projects beginning around 1958, Christo and Jeanne-Claude transformed that industry's excesses and its inefficient objects into signifying units that challenged its supposed clean fluidity and rematerialized its dirty reality. While Total's designers sold a smooth scheme of distributed power, Christo and Jeanne-Claude envisioned blockage and breakdown. Where Total sold designed flows, Christo and Jeanne-Claude revealed design flaws. Stacked and wrapped in galleries, alongside highways, on narrow Paris streets, or even, Christo and Jeanne-Claude imagined, in the Suez Canal, the barrels would halt, rather than facilitate, oil's circulation. As a type of what Bill Brown has termed "meta-objects," these barrels, when "misused" by artists, exposed French oil's "problematics of materiality and materials."8 If, as Brown argues, works of art "preserve" "the character of things," Christo and Jeanne-Claude's barrels preserved the character of the oil.9 As empty (but never only empty) containers, they threatened to reveal that character in all of its "thingness" — the crude materiality through which oil shaped France's object world and its subjects.

Though long dismissed as prototypical examples of apolitical neo-avant-garde spectacle, Christo and Jeanne-Claude offered, in the barrel projects analyzed here, a powerful criticism of the oil industry whose rise closely tracked the modernist century. Reading their barrels in this way points to an important tension in modernism between materiality and value, the "productive quality" of which, Amelia Jones argues, has too often been "spuriously resolved in favor of the immaterial through subjective assertions of truth value."10 Jones points to Clement Greenberg (along with Michael Fried), who "epitomized this sleight of hand by which the materiality of the artwork was both glancingly acknowledged . . . and simultaneously disavowed through value-laden interpretations relying on abstract concepts of form."11 Refusing this disavowal of the material need not, as the social history of art has long demonstrated, mean dispensing with questions of value. In the case of Christo and Jeanne-Claude's barrels, one need only consider these material objects' central historical role in one of modernity's most significant and enduring value systems, the very value of which — price per barrel — they continue to define even in their relative absence from an industry now connected more often by tankers and pipelines. Here we find value, just not the transcendent one hailed in Greenberg's strain of criticism.

But I am interested in more than simply making the point that oil barrels are units in an economic system. Rather, I seek a reading that moves between a historical materialist account of the conditions that shaped and were in turn shaped by Christo and Jeanne-Claude's barrel projects and a materialist analysis that attends to the work that barrels did as objects and artworks. Filled with crude and transported by machines and laboring bodies from (often colonial) extraction zones and distribution hubs to sites of consumption and, eventually, noxious waste — only then to be recovered and recoded as art objects — the barrels were essential vessels for material and meaning, but they were no less agents in industrial and artistic projects whose forms and experiences followed from and responded to their shaping objects' physical and phenomenological affordances.

This method of reading goes further, I hope to demonstrate, when performed in dialogue with the broader visual culture of oil that included Total's advertising campaigns. Competing on a shared visual discursive terrain, Total's design for oil-systems thinking sought to fashion the same subjects and objects in oil-centric terms while concealing their material costs. Moving between the worlds of fine art and corporate publicity need not flatten their important differences but rather allows each to illuminate the other. Here I will be interested, for instance, in how the signifying work barrels performed in Total's design system informs a reading of barrels as raw materials for art, and, reading the other way, how a materialist analysis of barrels can be extended to Total's ads as they circulated not just as immaterial images to be read but also as physical objects that turned through the hands of midcentury magazine readers. This mode, I hope to suggest, offers opportunities to perform what we might call a critical act of infrastructural visibility: a form of rematerialization that refuses "petrotopian" normalization in ways that may be up to the task of challenging the corporate visual culture that includes, but also goes beyond, forms of art patronage through which oil companies still seek, though under increasing pressure, to "wash" away their material realities.

The French World of Oil

The design vision developed by French oil interests in the post-1945 years was neither new nor unique. Since the early twentieth century, oil purveyors in the United States and Britain had used visual design, photography, and film to sell both their corporate brands and the value of petroleum itself. Positioning themselves in an image culture that dated to the early days of prospecting in Pennsylvania, oil barons such as Edward Doheny began, as LeMenager notes, to develop "a genre of pro-oil propaganda in the 1920s."12 In the UK, British Petroleum began film production at least as early as 1920, while Shell, after commissioning a report about the potential value of developing a film program from John Grierson, the so-called "father" of British documentary, did the same in 1933.13

In France, the story was different. Although the French had long used petroleum-derived products, they did not develop a significant industry of their own until midcentury. Up to that point, most French oil came from abroad, and just a fraction of those reserves were under French control. The most significant source was a 23.75% share in the Turkish Petroleum Company wrested from Deutsche Bank as part of World War I reparations.14 This share was managed, beginning in 1924, by the newly created Compagnie française des pétroles (CFP) and its primary backers, Desmarais frères, a firm specializing in vegetable oils used, among other purposes, for lamp fuel. Only in 1939 did French prospectors discover significant petroleum reserves on domestic soil, beginning with a gas deposit near the Spanish border in the Haute-Garonne overseen by the new Régie autonome des pétroles (RAP, later part of Elf Aquitaine). During World War II, French oil exploration expanded in the southwest under the aegis of the Société national des pétroles d'Aquitaine (SNPA). But the real push began in 1944, with the quick proliferation of an alphabet soup of state and private oil institutions: the IFP, BRP, SN REPAL, CFPA, and others.15 Over the two ensuing decades, these and other new companies oversaw expansive prospecting missions across France and its colonial empire.

By 1961, the year petroleum first surpassed coal as France's and the world's leading energy source, French producers were supplying around 94% of the nation's energy needs.16 Looking back, we might readily take for granted that this success was the logical outcome of petroleum's superiority as an energy source and assume that it was thus destined to achieve its position at the top of energy markets. French oil companies, however, recognized their contingent status, both in relation to competing energy forms and in a complexly competitive oil market.17 This competition was increasingly driven by images. During the 1950s, the coal industry, still France's leading energy source, promoted its reconstruction and modernization through significant film and photography campaigns that enlisted important industrial film directors such as Henri Fabiani and Roger Leenhardt as well as photographers including Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, Marc Riboud, and Roger Schall.18 Similar forces were at work in the nuclear program, and French filmgoers in the 1950s would also have seen industrial shorts about the promises of hydroelectric power and, in the next decade, solar energy. Petroleum companies responded in kind. Their significant visual culture programs, which reached particular volume in the 1960s, included film, advertising, and art patronage. During these years, such programs brought into focus a design vision for an oil-powered future.

Total's "bon génie" and the Forms of Oil Design

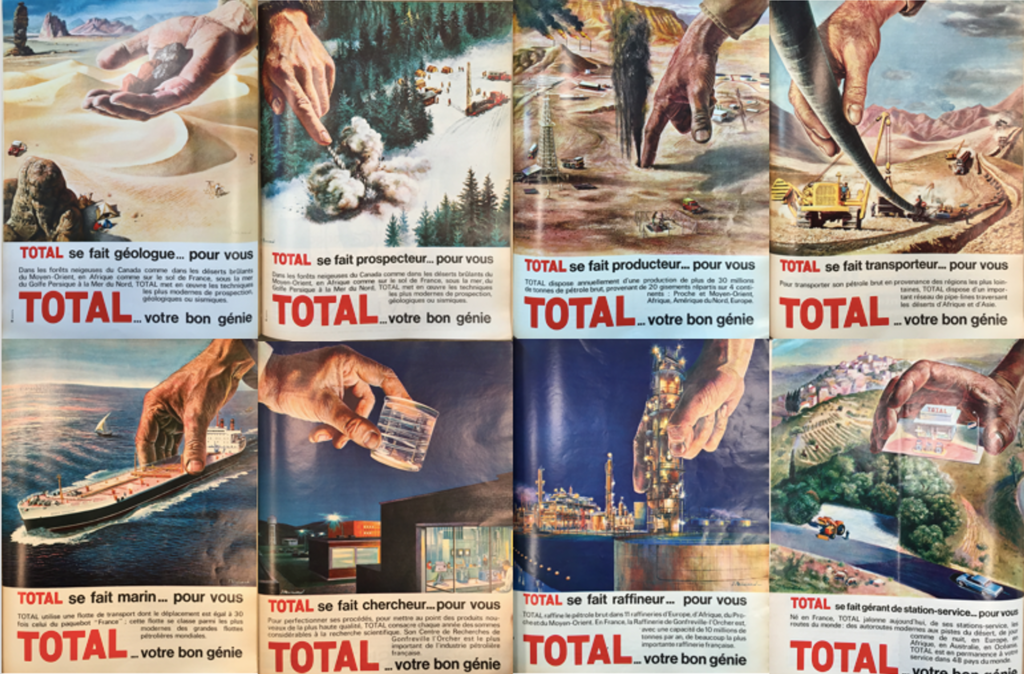

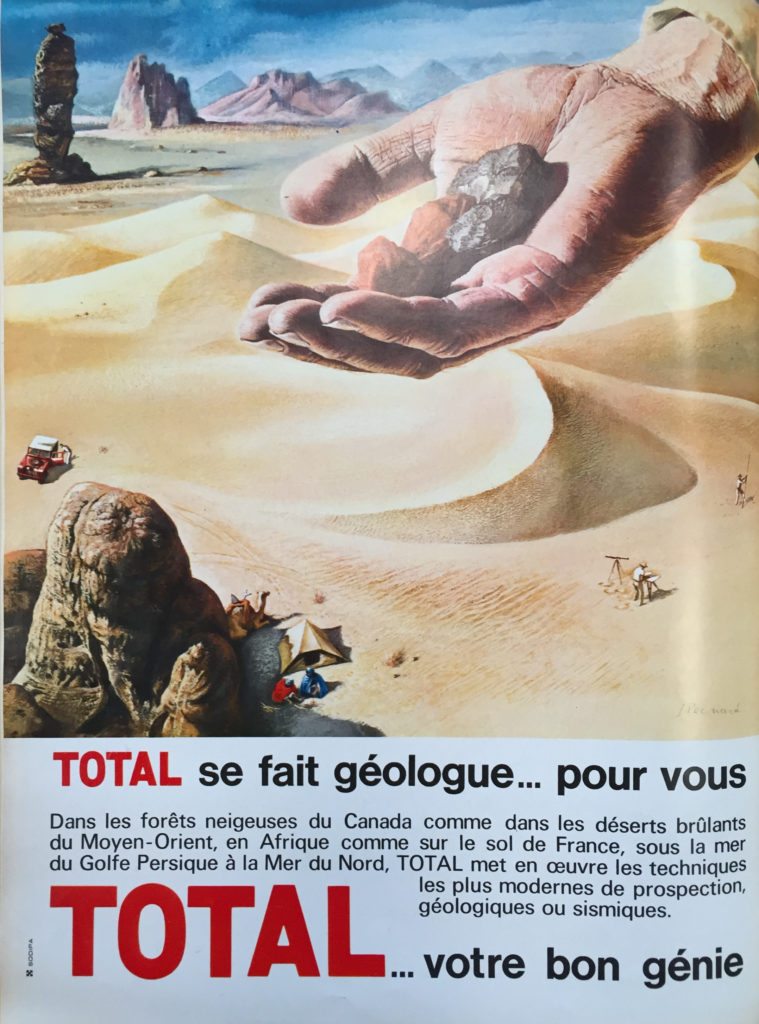

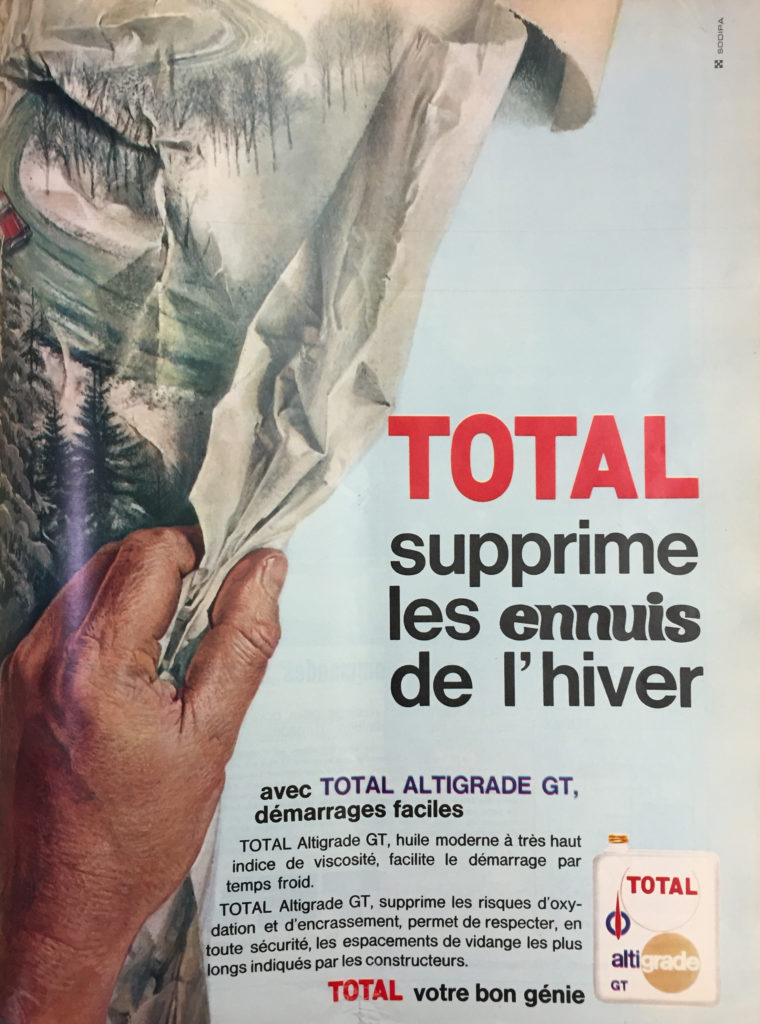

In the summer of 1965, the CFP outlined one such vision for French readers in an evocative advertising campaign developed by the its distribution wing, the Compagnie française de distribution (CFD), under the Total brand. Between May and August, ten separate ads (figure 3), running weekly in the popular illustrated magazine Paris Match, narrated a fantasy world of environmental design, systems thinking, and modernist resource management told through a story of corporate oil's powerful beneficence.19 With drawings by Jacques Pecnard, a twenty-five-year veteran of book, magazine, and newspaper illustration, the series promised a kind of corporate plasticity. Total, the ads told readers, was their genie in a bottle, and it was a good "génie," a word in French with a handily supple meaning, signifying not just the spirit of the Arabian tradition but also, from the Latin, a "genius," or, as le génie, "engineering." This was petroleum engineering with a genie genius behind it — an engineer with designs on an oil-built world.

Total's PR team conjured this genie at a significant moment for the French petroleum industry. Having recently surpassed coal, the petroleum sector was on firm footing, but it still faced an uncertain future, not least because one of France's prime sources of crude was newly independent Algeria, which was making increasing demands on its rights to the oil reserves resting beneath its now-sovereign sands. For individual oil companies, all of which relied upon Algerian sources as one (if not the only) part of their supply base, the question of finding a market was no less fraught. French petroleum consumption was on the rise, but whether sufficient demand could be assured for petroleum — and for the right kinds of it — remained an open question.

Efforts to answer this question had driven the creation of Total itself. First launched in 1954, the brand signified, in its tricolor palette and English name, the CFP/CFD's attempt to marry nationalist appeal with international ambition.20 In 1965, Total-CFD merged with Desmarais frères, expanding the CFP's control over French petroleum distribution and extending supply lines that connected holdings in the Middle East and Algeria to French gas markets. The move was part of the CFP's struggle to maintain its market share in the face of heated competition from foreign and domestic rivals. The 1960s witnessed a significant increase in petroleum publicity, driven, literally, by the rapid rise of French automobile ownership, which nearly doubled between 1960 and 1969.21 Shell, for instance, was marketing its new gasoline brand, ICA, with the slogan "C'est Shell que j'aime" developed by French PR pioneer Marcel Bleustein-Blanchet, whose company Publicis helped make Shell's French affiliate one of the nation's biggest advertisers. The ad notably appears in Godard's Bande à part/Band of Outsiders (1964) as just one of the director's frequent references to the world of driving (figure 4). Esso Standard introduced its famous tiger logo, which makes its appearance in Godard's La Chinoise (1967) (figure 5). And Total's chief domestic competitor, the state-owned Union générale de distribution (UGD), was working to consolidate its three existing brands, Avia, La Mure, and Caltex, a project that would eventually lead to the launch of Elf in April 1967. In short, branding and marketing were high on the French oil agenda and had become prominent enough to make ready references in French art cinema.22

Corporate competition, however, was not CFP/Total's only concern. The company also needed to find ways to expand French consumer gas consumption. The problem had to do with the materiality of its Algerian oil supply. The Iraqi petroleum that had previously been its primary source was a heavy crude that required complex refining processes but was good for the industrial applications and heating oil that France needed as its politicians forced a shift away from coal. The Algerian crude, in contrast, required less refining but consisted of a higher gas content. While gasoline use was expanding in proportion to rising automobile sales, demand remained too low to allow Algerian petroleum to achieve a market value that would make up for its comparatively high production costs. The direct result of this material problem, for Total, was the emergence of the UGP, which had been created in 1960 by the French state to ensure that Algerian oil reserves would have a consistent buyer.23

It was in the context of these competing attempts to expand the gasoline market that, in the summer of 1965, Total launched its extended advertising campaign offering French consumers a vision of the petroleum system and its designs for a newly oil-powered nation. The ads articulated Total's world design through its génie's ten forms. Each week, readers witnessed Total's capacity to adapt itself to every petroleum need, whether as the geologist, the prospector, the producer, the transporter, the sailor, the researcher, the refiner, the truck driver, the plane refueler, or the pump attendant. Like Total's oil, the forms of which defined both its functions and potential market value, so Total would define and sell not so much oil itself as the malleability of its own corporate form — and ultimately the mobile forms of living it made possible.

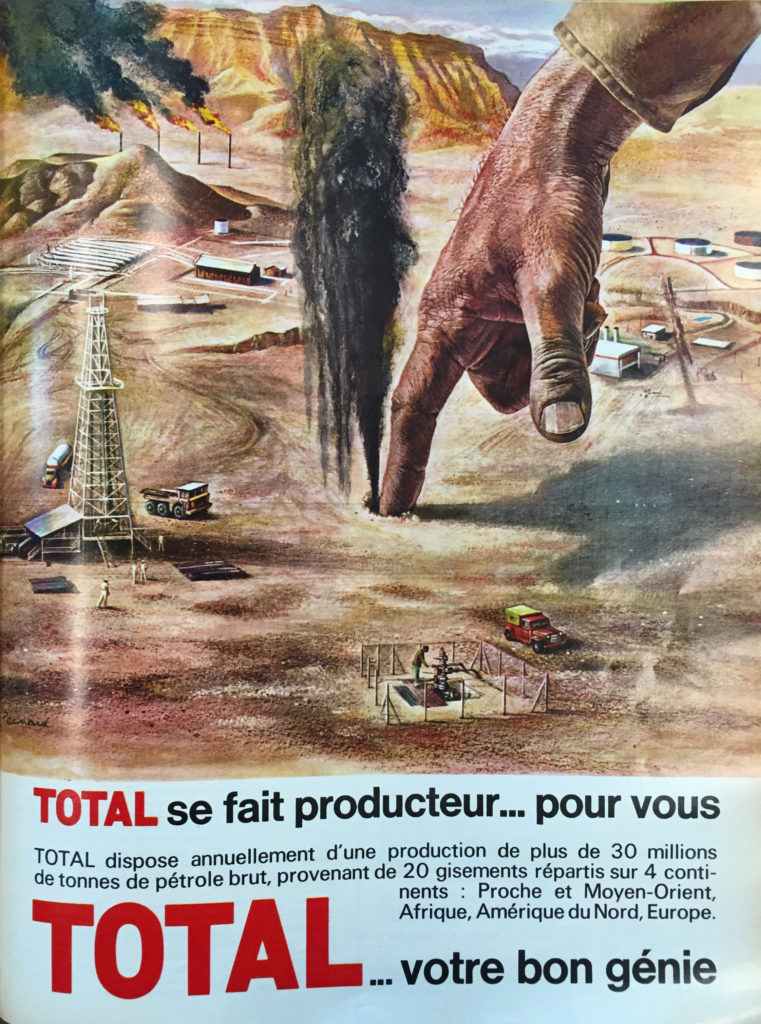

The génie ads gave this formal thinking visual form. Moving across the lifeworld of oil, they illustrate the stages in a design process through which a crude resource became a refined product — and then a set of conditioned practices. Aside from the text boxes that appear below the drawings, the ads' primary unifying element is a giant, Caucasian hand, its tan, weathered skin signifying the human work behind this designed world. Clearly meant to signify Total's corporate reach, the hand invokes the world-shaping power of architecture figured most famously by Le Corbusier's pointing mastery over La Ville Radieuse.24 Meanwhile, it erases the hands of labor by consolidating into a single figure the work of the many. In rendering labor power as corporate power, the ads illustrate Timothy Mitchell's argument that oil's supremacy resulted in part from the degree to which it afforded oil companies, unlike their coal competitors, a supply chain with fewer workers and thus less risk of labor strife.25

The hand also embodies the anthropocentric thinking that drove Total's design vision — a vision for an "Anthropocene" whose driving anthropos is made uniquely clear. That the ads figure this anthropos as hands, not humans, lends them particularly rich heuristic value. Following Martin Heidegger, who argued in his 1954 book (based on the 1951-52 lectures) What is Called Thinking?, that "all the work of the hand is rooted in thinking," this ad campaign's "handiwork" reveals a great deal about the systems of thought behind it.26 Thinking, in Heidegger's words, "is a craft, a 'handicraft,'" and indeed oil thinking, in Total's ads, is a labor of metaphorical hands that craft the world. For Pecnard, Total's oil crafting becomes a study in manual gestures. The giant corporate hand points and prods, places and presents, grips and guides. In one ad, from May 29, the prospecting hand, throwing lightning from a finger, becomes godlike in its power to tear the Earth asunder (figure 6). In another, the same finger pierces desert soil, producing a gushing spray of dark liquid that mirrors the black smoke streaming from four flares in the background (figure 7). Humans and machines are toys in this design world: matchbox cars and model derricks, tankers set softly upon sea surfaces, and glider planes lifted gently towards the sky. Carving a road through the forest becomes a mere swipe of the finger, while a petrol station fits, puzzle-like, into a ready rectangle. Put in Heidegger's terms, through these ads — especially the geology, prospecting, and production versions (figs. 6-8) — Total sought to redefine the world by demonstrating how its "readiness-to-hand" for the company (as energetic material) rendered it "present-at-hand" for consumers (no longer simply existing but now recognized as an industrial resource).

Figure 6: Paris Match (May 29, 1965)

Figure 7: Paris Match (May 29, 1965)

Figure 8: Paris Match (May 22, 1965)

Figure 9: Paris Match (December 18, 1965)

By 1965, with oil power on the rise and its infrastructures, from source to market, under at least a degree of French control, this vision of a France put in place by the hand of oil was coming into tenuous focus. To make Total's position more concrete, the ads insisted that it was readily at hand. Given the company's widening control over vast swaths of oil-rich regions and the transport routes connecting them to energy markets, it's no surprise that Total imagined itself as larger-than-life. The world, these images hopefully proposed, was a dollhouse and train set put in motion by oil's guiding hands. But this scaled-up thinking was also a form of speculation, and its projection had important ideological consequences for the oil vision Total was selling to French consumers. An abstract lifestyle was being envisioned, one designed for an imagined world of gas-guzzling drivers held comfortably in the hands of powerful institutions.

The Paris Match ads point to the tenuous balance between large and small upon which teetered Total's designs for an oil-powered world. How could the company square its larger-than-life aspirations with the need to manage the everyday practices of ordinary people? In scaling itself up to gigantic proportions, the company activated, in a banal way that nonetheless resulted in striking visual forms, what Susan Stewart has described as "a metaphor for the abstract authority of the state and the collective, public, life."27 At the same time, in positioning Total as the illustrated world's guiding hand, the ads anticipate how, in Stewart's words, "the gigantic, occurring in a transcendent space, a space above, analogously mirrors the abstractions of institutions . . . [and increasingly] the abstractions of technology and corporate power."28

By making abstract corporate power large, the ads make humanity small. The imagined consumer — who appears only seldom in the ads, whether as a driver or the occasional worker — is miniaturized, and thereby formed as the liberal subject of a vision articulated by a private entity that also served France's hybrid public-private oil-backed economy. This attempted subject formation — one which includes the othering of former colonial subjects who are left, in the May 22 prospecting ad (figure 8), literally in the shadows — takes place within each ad, but also, and more insistently, over the course of the full eight-part series: a narrative played out, like serial fiction, over the course of a summer. As Stewart reminds us, narratives "seek to 'realize' a certain formation of the world," and, in particular, in the "dream of the inanimate-made-animate," we find the essence of narrative's "desire to invent a realizable world, a world which 'works.'"29 In this case, Total, across a series of drawn images, sought to animate (from animare, "to instill with life") itself and its worlding ambitions. Stewart notes that while the gigantic had once been part of the vernacular, during the twentieth century it also became "the domain of commodity advertising," from the Jolly Green Giant to Mr. Clean. Just as those giants were "nothing more than their products," so too Total's nameless hand serves to naturalize oil power, which is "made magically to appear by the narrative of advertising itself."30 These ads, in other words, did not merely sell oil; they aspired, more broadly, to conjure oil's powers of world creation.

To fully account for these ads' power, however, we must not forget that they were more than just aspirational images. We also need to reckon with their more literal handiness — as material objects held in consumers' page-turning hands. Seen in this way, Total's ads offer a series of object lessons in the double movement whereby, in Stewart's words, "the miniature moves from hand to eye to abstraction, [while] the gigantic moves from the occupation of the body's immediate space [the magazine held literally in one's hands] to transcendence [the godlike hand within the ad's exaggerated world] . . . to abstraction [the prospective power of what I'm calling the "oil-built world"]."31 Put another way, we might locate these ads' special craftiness in the play of scales whereby Total's hands are, at once, larger-than-life (when imagined in the ads' diegetic world), but also lifelike and tangible (when seen alongside the reader's own hand).

In this sense, the craft, for Total as for Heidegger, had two sides. The hand's peculiarity, Heidegger argued, was its capacity not just to "grasp and catch, or push and pull," but also to receive and welcome, and to receive "its own welcome in the hand of others."32 In these ads, working as both images and material objects, Total seeks a similar movement. On the one hand, its illustrated hands grasp the world, pushing and pulling it into place and crafting it in oil-centric form. On the other hand, the ads encouraged readers, flipping through the pages of Paris Match, to take Total's vision into their own hands, the ones there holding this world in view.

Such reflexivity becomes palpable in a new ad, published later that year, in which the hand reappears but in a new form (figure 9). Rather than merely placing a new piece of oil infrastructure in this wintry world, this hand peels back the image to reveal a more powerful vision: a Total genie capable of eliminating winter altogether — global warming as an implicit promise. The world of these ads, this new one suggests, may be an illusion, but that revelation does not apply to the (corporate) hand, which remains firmly in place, there to guide the reader's own.

The link between Total's hand-crafted vision and Heidegger's philosophy of gestural thinking goes at least one step further. In 1955, Heidegger had signaled petroleum's powerful but tenuous importance by rearranging his theory of technology to give it momentary prominence. No longer a story of rivers and dams, Heidegger's theory of "enframing" now used a petro-powered metaphor: nature was "a gigantic gasoline station, an energy source for modern technology and industry."33 Though it would soon, Heidegger predicted, be replaced by atomic energy, for now oil reigned supreme: technological essence was essence [Fr: gas].

Heidegger's larger point, notably delivered as an address at the anniversary celebration in his hometown for composer Conradin Kreutzer (1780-1849), was about the status of thinking in a world increasingly dominated by calculation.34 If the world had been reconceived as a gas station, it was because the human relationship to the world had been radically reconfigured under the impetus of technology. Atomic science was this impetus's current extension, and the bomb its most visible but not most significant risk. Of greater concern, Heidegger insisted, was society's incapacity to confront the "uncanny change in the world" as it became entirely technical.35 Rejecting technology offered no salvation, he argued; rather, one needed to develop a different comportment to the technological world, one that would allow the individual to retain a non- (or more-than-) technical relationship to things. A world increasingly dominated by calculation required such meditative thinking as a safeguard against technical overdetermination.

Total, with its giant hand — the grasping organ that "designs and signs" — saw things otherwise. It envisioned the calculated world Heidegger dreaded: an oil-built world, the crude designs of which were coming into form, with nature's "gas station" as its source and Total its brand. In this world, one's proper relationship to technology need not involve thinking, for Total, as the Paris Match ads promised, was there to do it for you. Any comportment to oil's new material world resembling the one described by Heidegger would have to be found elsewhere.

Designed Flows and Design Flaws: Christo and Jeanne-Claude's Art of Oil Barrels

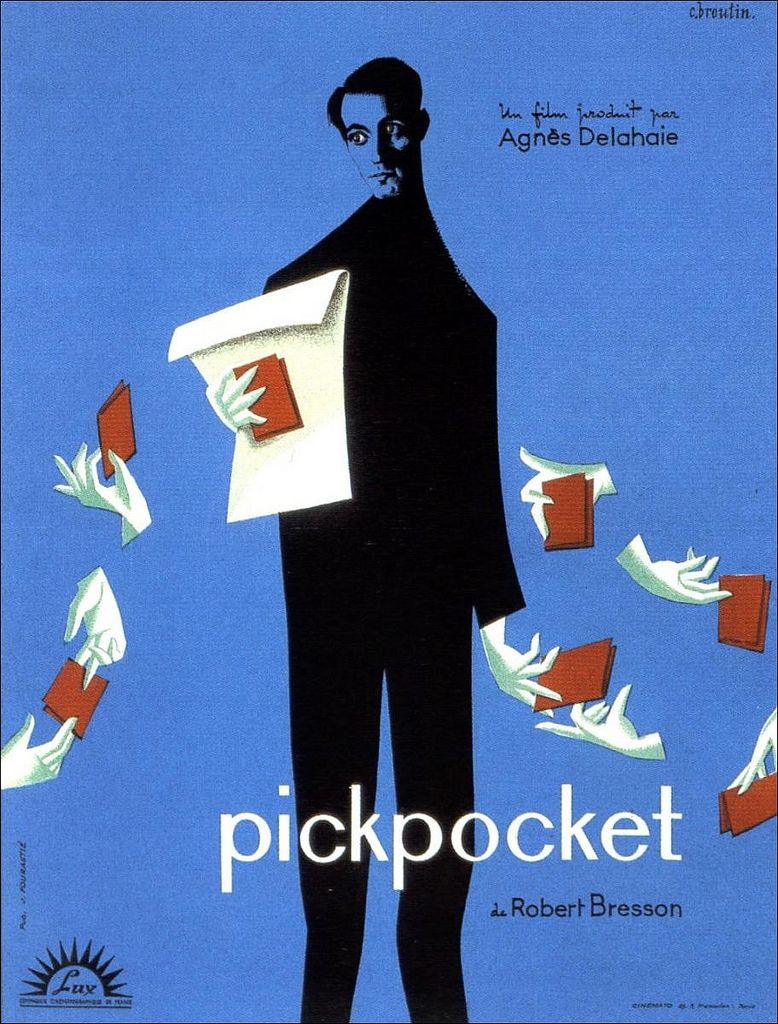

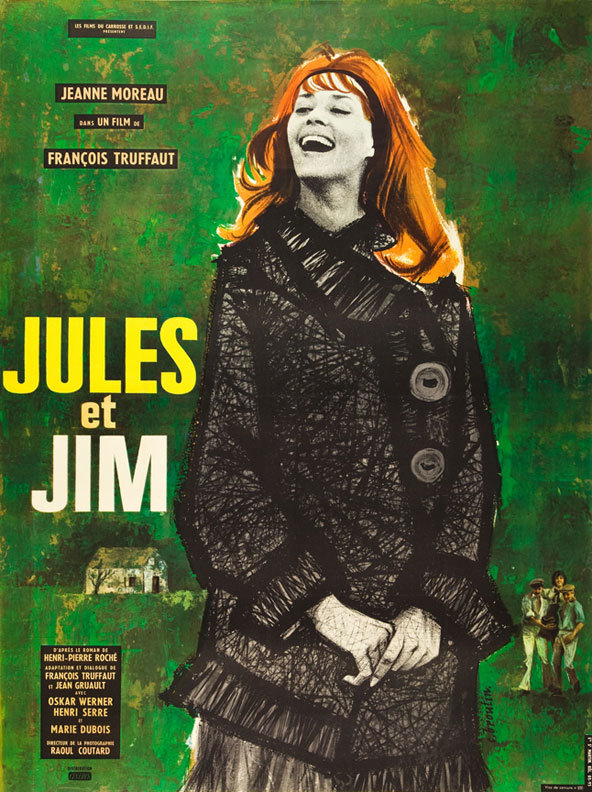

Total's 1965 ad campaign offers only a hint, but still a useful one, of how oil PR drew from the French art world. Sponsoring art shows in Paris or tapping the talent of the French film world, most famously in Alain Resnais's Pechiney-sponsored 1958 film Le chant du styrène, was just one part of the petroleum and petrochemical industries' broader efforts to use French art to define the value of French oil.36 In the area of graphic design, film and art overlapped. Earlier in 1965, Total ran a first version of the Paris Match ads (figure 10), this time with illustrations by Christian Broutin, an artist best known for his film advertisements. Broutin's poster for Robert Bresson's handsy 1959 film, Pickpocket, for instance, features nine white hands in a gestural play of grasping, holding, placing, and passing (figure 11). (Look, too, at Jeanne Moreau's hands, sketched out, in a style that evokes then-star Bernard Buffet, in Broutin's poster for François Truffaut's 1962 feature Jules et Jim (fig.12).)

Broutin did numerous other film poster designs, some of which call to mind Saul Bass, as well as campaigns for French department stores including the Galeries Lafayette. He and Total's other ad illustrators were part of a new wave of French poster designers emblematized by Raymond Savignac, the illustrator known for his playful images but who also articulated a Fried-like claim for the advertisement, arguing that its graphic form must be pure and the reading of it "instantaneous."37 As Roland Barthes put it, Savignac's advertisements were about "seeing the sense come into being before our eyes," and thereby creating an "art of the imminent future" — a "subtle tense which is present and future at once."38

The artist couple Christo and Jeanne-Claude have long been exemplars of something like the opposite of Fried's ideal. More often denounced as spectacle makers of the French neo-avant-garde, they have often been dismissed, in terms explicitly derived from Fried, as purveyors of literalist theatricality. Here I want to make the case that they deserve more credit than that, for what their early work with oil barrels made possible was a very different claim about the oil industry's designs and its systems thinking than what we find in the image world of oil advertising.

In appealing for a re-reading of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, I'm following the work done in recent years by art historians including Kaira Cabañas, Jill Carrick, and Hannah Feldman, each of whom has called attention to the political interventions of the couple's contemporaries, some affiliated with the movement known as Nouveau Réalisme. Examining a range of figures including Raymond Hains and Jacques Villeglé, Isidore Isou and the artists associated with Lettrism, as well as Daniel Spoerri, Martial Raysse, Niki de Saint Phalle, and Jean Tinguely, such work has challenged the idea that French art in the 1950s largely traded the criticism of the historical avant-garde for the spectacle of post-WWII consumerism. As Cabañas succinctly puts it about the work of the Nouveau Réalistes, "these artists extended [the critique] along different lines."39 Rather than simply turning art into a theater of commodities, as some have charged, artists such as Hains and Villeglé with their "lacerated" posters, Raysse with his displays of plastic objects, or Tinguely with his window-display machines, found modes of political action within the spectacle.40 This, I will argue, was similarly the case for Christo and Jeanne-Claude, even if the artists themselves downplayed the politics of their aesthetics.

Christo began working with oil barrels in 1958 (figure 13).41 He had recently arrived in Paris by way of Vienna and Geneva after fleeing his native Bulgaria. As an unknown artist making a living selling portrait paintings, he might just as easily (especially had he not met Jeanne-Claude) have become one of Total's Paris Match illustrators. But meanwhile he was also wrapping, painting, and stacking empty paint cans in his Paris studio. These were his first sculptures. Seeking to scale up this practice, he found the ideal object in the junkyards on Paris's industrial periphery (figure 15). He carried the barrels home, one by one, and began wrapping them in canvas treated with lacquer and sometimes coated with sand. He stacked some of them, first in his studio's basement and then in a garage owned by his friend, the painter Jan Voss, in Gentilly. There he had ready access to more barrels, which he used in varying configurations to make sculptures, both in the studio and, more fittingly, mounted as sly monuments to oil-powered mobility along the suburban roadside (figure 14).42

In 1961, he was invited to install some of these barrels at an exhibition in Cologne. In breaks during the installation, he and Jeanne-Claude wandered the nearby docks, where they found a wealth of barrels that they convinced the dockworkers to help them assemble into large sculptures which they then wrapped.43 During the exhibition, the Berlin Wall went up, and on return to Paris the pair, no doubt influenced by the Wall and Christo's own escape from Communism in 1957, developed a plan to barricade the rue Visconti, the narrowest street on Paris's Left Bank. Despite failing to receive permission from the city, on the night of June 27, 1962, they erected the barricade, which stood only long enough for a few photos before city police demanded its removal.44

They named this work "Rideau de fer" ["The Iron Curtain"] in recognition of the Berlin Wall, but it also evoked a long tradition of revolutionary Parisian barricades and the power they had as images as much as military infrastructures.45 More to the point at the time, this barricade may have evoked, for some at least, the war in Algeria, the violence of which continued, despite the March ceasefire, in the leadup to the decisive July 1 referendum in Algeria. As Matthias Koddenberg has argued, it would not have been difficult to intuit the politics of "plac[ing] their wall of oil barrels right in the middle of a city that was still shaken by violent riots" and in the context of street fighting in Paris and Algiers.46 Koddenberg, following earlier scholars including Tom McDonough, highlights the graffiti that appears on the walls beside the barrels, including swastikas and the FLN (National Liberation Front) slogan: "Le fascisme ne passera pas!"47 Reading this graffiti more than the barrels themselves, such work has hastened to associate the "Rideau de fer" with the decolonization struggle in Algeria.

Such analyses, for all their value, too quickly move past the meaning of the barrels themselves. In the context of France's emerging oil power, this barricade also had a point to make about oil.48 By 1962, after all, a significant portion of France's oil was coming from that same Algeria. To create oil-based barricades was to imagine the kind of block on the petroleum economy that French state officials had worked hard to avoid in the independence negotiations just concluded at Evian, but which would nonetheless come, less than a decade later, when Algeria nationalized the oil industry in 1971. The risk of the blockade points to one of these barrels' essential meanings — as objects — that we miss if we overlook their place in the history of oil.

The oil barrel had long been a central concern for oil and gas companies. In the 1860s, in the early years of petroleum prospecting in Pennsylvania, the barrels were in such high demand that their cost may at times have surpassed the value of oil itself. For this reason, but especially as a means to control the flow of oil and prevent bottlenecks and the potential for disruption to the supply chain, oil companies quickly moved to develop more efficient delivery systems, via pipelines, railway tank cars, and later maritime tankers, the first of which — the Zoroaster — crossed the Caspian Sea in 1878.49 By the early 1970s, the development of "supertankers" meant that increasing quantities of oil were being transported by sea. When it arrived in ports like Marseille, however, it still had to be moved and stored, and barrels remained one important means to do so, thus explaining why Christo and Jeanne-Claude could find so many of them in the Paris junkyards. Re-collected and stacked in alleys and galleries, these barrels demonstrated something that oil companies feared: the blockade. Even if, as Mitchell argues, oil's power lay in its anti-labor, anti-strike affordances, that power was by no means complete. The nodes in the oil network — places like ports and refineries, but also objects like the barrels themselves — were sites of risk.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude's oil blockades included not only the rue Visconti, but also grander visions such as the June 1968 proposal to blockade 53rd Street outside the Museum of Modern Art, New York (figure 16), or, more to the point here, the 1967 proposal to block the Suez Canal (figure 17), one of the major crossing points for oil tankers departing from the Middle East. Political readings of these works have been discouraged by a tendency to interpret the barrels as empty vessels, stripped of any symbolic value. Koddenberg points to Christo and Jeanne-Claude's own efforts to sidestep political readings: "Denying the existence of any kind of meaning or message in their works, they [instead] direct attention to the essential questions of art."50

Figure 16: Christo, "441 Barrels Structure" - "The Wall" 53rd Street between 5th and 6th Avenue (Project for June 9, 1968, The Museum of Modern Art N.Y.). Collage 1968. Photo: Wolfgang Volz. © 1968 Christo

Figure 17: Christo, "500.000 Barrels Structure - The Wall in Suez Canal" (Project for Temporary Monument Between Israel and Egypt). Collage 1967. Photo: André Grossmann. © 1967 Christo

But we need not blame the artists alone for depoliticizing their work, for of course this propensity to put the onus on "essential questions of art" was a dominant strand of art criticism in the early 1960s. Its language clearly marks the earliest writing about Christo by critics such as Lawrence Alloway and David Bourdon. Writing in the wake of Michael Fried's "Art and Objecthood" essay, Alloway and Bourdon set the standard narrative about Christo by defining his barrels as literalist objects.51 As Alloway put it in a description that has had long purchase, "the function of [his] objects is interrupted by Christo at the level of use, not of symbolism . . . he is violating our operational relationship to the objects."52 Alloway singles out the trade names on the barrels — Esso, Total, Shell, BP — arguing that by not effacing them, Christo "block[s] symbolic interpretation" of the barrels, an argument repeated by Bourdon, who writes that "by leaving brand names visible, [Christo] blocked any symbolic interpretations and reinforced literalist use."53

Reducing these works to Fried's language of literalism does a disservice to their conceptual potential. Though they have been read almost exclusively in this manner ever since, Christo and Jeanne-Claude's barrels might just as well have made visible to the French public in the late 1950s and early 1960s a material system and an ideology of concealment and control.54 This revelatory potential, moreover, functioned precisely through the play of surface and interior, the tension between fullness and hollowness, and the (political) projection of objecthood — the terms of Fried's argument, just put to different ends. In stacking and wrapping barrels, and by restricting movement, whether on the rue Visconti or in the gallery, Christo and Jeanne-Claude placed their viewers in a material system of petroleum exchange — a system that was, for the oil industry, wasteful and risky but flexible insofar as it made possible the packaging, containerization, and delivery of their product. In wrapping these barrels and using them as interchangeable parts, they created an opportunity to read this system. Contrary to what Alloway, Bourdon, and others have argued, this system was legible; the barrels were, as Olivier Kaeppelin proposed in an interview with Christo, "lexical units."55 For Shell, BP, or Total, especially in the context of their intensified branding struggle in the 1960s, their meaning lay in the barrels' colors and logos — on the surface. For Christo and Jeanne-Claude, it lay within, around, and between them.

The wrapping, which Christo first did with canvas and lacquer, then later with polyethylene plastic, helped activate this latent, more-than-surface-level meaning. When placed in sculptural formations or alongside petro-powered vehicles, the wrapped barrels, along with the juxtaposition of barrels of different sizes, shapes, and colors, disrupts the uniformity of oil distribution — challenging a trade that banked on controlled visibility. The barrels, a wrapper for the oil, there to keep the crude material clean and out of sight, were key vessels of this visual regime. To wrap them was to call attention to their materiality, their variability, the means of their portability, and the broader conditions that created that "immaterial" thing — energy — that had come to have such force in French state policy.

In their analysis of the surfaces and the wrapping, Alloway and Bourdon came closer to the reading I'm advancing here. For Alloway, Christo had begun an "exploration of the geometry of surfaces" that created "an ironic play between the new surfaces and the concealed supports."56 "The packaging," Alloway wrote, "obscured, wholly or in part, the core, but without destroying the impression of containment."57 Similarly, for Bourdon, "the physical reality of the contained object continue[d] to make its presence felt from within."58 In the case of wrapped barrels, that core, that physical reality, was of course oil, which though absent in these barrels, was made present when encased in canvas or plastic. As just a barrel in a junkyard, the barrel might be empty, but wrapped and recoded as art object, the barrel's core, the oil that defined its use, made its presence felt even in its absence. In this way, the barrels (re)introduced oil as what Bill Brown terms the "materiality effect," the perspective from which materiality comes to exist, or in Brown's words, "the end result of the process whereby you are convinced of the materiality of some thing."59 Wrapped and/or stacked in the gallery (figure 18), oil barrels reacquired a materiality that the oil industry sought to (turn into) refuse. To reproduce that materiality and thereby give oil presence in the decade divided by 1960 was a political act.

Put another way, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, in transforming the barrels into art works — and thus refusing their original use value — instead generated a "misuse" value, or what Brown defines as "the aspects of an object . . . that become palpable, legible, audible when the object is experienced in whatever time it takes (in whatever time it is) for an object to become another thing."60 If, as Brown argues, this "misuse value" precipitates "thingness," what Christo and Jeanne-Claude precipitated in their barrel sculptures was, in the most straightforward sense, the thing — the oil — they once held. But in a more abstract sense, it was the broader "thingness" that oil, in the work of the French oil industry and its artists, had come to signify: the vital, energetic, immaterial world petroleum promised. The thing about oil, for companies like Total, was that it should not be a thing; it should always already be all of those other things: vitality, prosperity, comfort, security. Christo and Jeanne-Claude's barrels called attention to this relationship between oil as a material thing, the objects that concealed it, and the many abstract things oil and its objects contained and created. If their sculptures were, in the language of Fried, "theatrical," it was by deploying this theatricality that the barrels made possible a politics of oil experienced in duration — the few hours, for example, during which Jeanne-Claude reportedly managed to convince the French police to allow the "Rideau de fer" to block the rue Visconti before it had to be removed.61

French art critics at the time, however, pushing the kind of readings that helped, more broadly, to establish Nouveau Réalisme's apolitical legacy, largely ignored this politics. For critic Pierre Restany, whose text appeared on the invitation to the barrel exhibition at his Galerie J, the barrel barricade captured the "fleeting beauty" of the port with its "strange temporary monuments, powerful shapes and immediate plasticity," all of which revealed the energy of work, an energy that Christo had monumentalized.62 Reviewing the show in Arts, Michel Ragon similarly described the barrels as "temporary monuments" snatched from their "fleeting lives" on the port.63 These few interpretations offered at least the implicit sense that Christo and Jeanne-Claude might be valorizing the labor of the dockworker, a familiar leftist move in 1950s France. But even so, they failed to take the next step of tracing the politics of the dock further up and down the supply chains linking the products it moved, especially the oil in those disposable barrels, which, as the gilets jaunes and the activists who threatened to shut down ports and refineries in January 2020 know well, is most at risk of blockage at these points of entry.

Despite such failures to politicize the couple's work, their oil barrels hardly deserve the dismissive interpretation, commonly launched at the Nouveau Réalistes, that they simply reproduced the spectacle form of the commodity. The oil barrel did represent a key commodity with a recognizable value — the price per barrel still used today (even, most often, without recourse to the barrels themselves). And it did fit into an aesthetic system that aimed to create symbolic value of a fetishistic sort. But it was also not the same kind of consumer object. Oil companies, as Total's Paris Match ads illustrate, had less interest in making oil itself visible than in selling the things oil made possible: the lifestyle, the oil-built world. To bring the dirty barrel from the docks or junkyards into the streets of Paris or its galleries was to disrupt that aesthetic system and its claims to a clean, immaterial vitality. To use barrels as barriers was to call attention to oil's circulation in a global economy and France's uncertain place in it. Finally, to call attention to France's place in the global economy of circulating petroleum commodities was to highlight Algeria's enduring significance in the physical and discursive spaces of the French metropole.

Glorious, Destructive Design

The oil-built world imagined and sold by companies like Total and resisted, however implicitly, by artists like Christo and Jeanne-Claude was a key component of the modernization projects and economic abundance that have long defined this period as the so-called "Trente glorieuses." These "thirty glorious years" came to an end in no small part thanks to the oil "crises" of the mid-1970s. More recently, however, this period has acquired a new name, what Christophe Bonneuil and Stéphane Frioux have termed the "Trente ravageuses," so named for the decidedly negative, or at best ambivalent outcomes of France's modernization projects, including social inequality, failing infrastructure, and environmental degradation.64 Whether "glorious" years or "destructive" years, these were oil years, for it was cheap oil that powered French modernization, and it was and is cheap oil that has driven the global devastation otherwise known as global warming or climate change.

In recent years, before being overwhelmed, like most everything else, by COVID-19, a French political crisis of proportions arguably not seen since May 1968 has called attention to the murky uncertainty we face in a world with less oil, or at least less cheap oil, but no fewer ecological consequences. I'm referring to the gilets jaunes, a movement — if it still is or ever was one — whose mystique comes in part from the visibility cloaks that gave it a name and mark it as an explicitly driver-led initiative. Its protests have been marked by numerous contradictions and an often-amorphous agenda, but at their heart is the seeming aporia of oil. Having launched these actions out of a frustrated demand — shaped by declining purchasing power and the increasing necessity of auto-mobility — to preserve cheap gas at the pump, many of the figures who helped spark the movement have nonetheless insisted that driving, or at least driving oil-powered automobiles, is not the ultimate goal.65 Meanwhile, these manifestants, like many before them, have recognized that one means to disrupt French politics is to stop the flow of oil, whether at petrol stations, refineries, or by barricading the ports.

Among the most important lessons to come out of the protests has been recognition of the problems' structural roots.66 Many of the protestors have no problem with green politics or even, in principle, the gas taxes that Macron promised would "make our planet great again" but instead sent many of his citizens into the streets. Rather, the moment has offered an opportunity to express the fear and uncertainty of being, as some protestors put it, trapped in lives they hadn't chosen. Many of the gilets jaunes don't want to have to drive, to buy gas, or to destroy the planet. This is simply the life they have been forced into.

Was this not the trap set by oil and gas promoters during those glorious, devastating years? The gilets jaunes insist that we recognize the design flaws in a France built in the image of oil. Selling an immaterialist story about power and plenty, all while remaking France in the image of highways and cars and suburbs, the French oil industry and the government that gave it power helped create the car culture that is this trap.67 They set a horizon of expectation — a bounteous future of material wealth and immaterial vitality for all — that has not been achieved. Today, French drivers and gas consumers are living on that horizon, which looks rather different from what was promised in the 1950s.

The gilets jaunes may not have the answer, but they did, as Didier Fassin and Anne-Claire Defossez argue, create "an event in the strong sense of the term — that is, a moment which imposes a temporal rupture in the course of things."68 In doing so, they may have the virtue of encouraging us to look back at a material history that asks, how ever did we get here? That history — and the gilets jaunes in their high-vis vests — can also serve to remind us to be hopeful about the power of visibility and of images to shape political will and give power to ecocriticism. But not too hopeful. After all, as the Total advertisements discussed here should remind us, petroleum visual culture holds its own seductive power — a power that has allowed the industry to sow doubt about its role in driving ecological devastation. As that kind of visibility suggests, we'd best not forget about the oil companies and their image power, for if there's anything about which we can be sure, it's that they don't need to be reminded.

Brian R. Jacobson is Professor of Visual Culture at the California Institute of Technology. He is the author of Studios Before the System: Architecture, Technology, and the Emergence of Cinematic Space (Columbia University Press, 2015) and editor of In the Studio: Visual Creation and Its Material Environments (University of California Press, 2020), winner of the 2021 Society for Cinema and Media Studies award for Best Edited Collection. He is writing a book about art and oil in France.

References

- Mel Evans, Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts (London: Pluto Press, 2015). [⤒]

- Nan Goldin, "The Uses of Power," Artforum International, January 2018. [⤒]

- For an overview of the gilets jaunes, see James McAuley, "Low Visibility," New York Review of Books LXVI, no. 5 (March 21, 2019): 58-62. [⤒]

- For one useful account of the heuristic value of studying resource industries through aesthetics, see Brent Ryan Bellamy, Michael O'Driscoll, and Mark Simpson, "Introduction: Toward a Theory of Resource Aesthetics," Postmodern Culture 26, no. 2 (2016). [⤒]

- Stephanie LeMenager, Living Oil: Petroleum Culture in the American Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 74. [⤒]

- Daniel Worden uses the phrase "fossil-fuel futurity" to describe the ideology that American popular culture has often normalized by naturalizing oil-dependent modes of life while dissociating them from oil itself. See Daniel Worden, "Fossil-Fuel Futurity: Oil in Giant," Journal of American Studies 46, no. 2 (2012): 442. [⤒]

- Important examples of scholarship about this more seldom-analyzed work of oil industry visual culture include: Mona Damluji, "Petrofilms and the Image of Middle Eastern Oil," in Subterranean Estates: Life Worlds of Oil and Gas, ed. Hannah Appel, Arthur Mason, and Michael Watts (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015); Mona Damluji, "Visualizing Iraq: Oil, Cinema, and the Modern City," ed. Matt Delmont, Urban History 43, no. 4: Urban Sights: Visual Culture & Urban History (November 2016); Rudmer Canjels, "From Oil to Celluloid: A History of Shell Films," in A History of Royal Dutch Shell, ed. Jan Luiten van Zanden (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 6-33. I have previously written about corporate oil films in Brian R. Jacobson, "The Shadow of Progress and the Cultural Markers of the Anthropocene," Environmental History, no. 24 (2019): 158-72; Brian Jacobson, "Big Oil's High-Risk Love Affair with Film," Los Angeles Review of Books, April 7, 2017. [⤒]

- See Brown's entry in Emily Apter et al., "A Questionnaire on Materialisms," October no. 155 (Winter 2016): 13. [⤒]

- Bill Brown, Other Things (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 11. [⤒]

- See Jones's entry in Martha Rosler et al., "Notes from the Field: Materiality," The Art Bulletin 95, no. 1 (2013): 17. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- On the early image of oil in Pennsylvania, see Brian Black, Petrolia: The Landscape of America's First Oil Boom (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000); LeMenager, Living Oil, 94-96. [⤒]

- On Grierson's work for Shell, see Rudmer Canjels, The Dynamics of Celluloid on the Road to Independence: Unilever and Shell in Nigeria (Hilversum: Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld en Gelu, 2017), 58. [⤒]

- In 1937, for example, 40% of French petroleum imports came from Iraq versus 22% from the United States, 9% from Venezuela, and 8% from Romania. See Samir Saul, "Politique nationale du pétrole, sociétés nationales et « pétrole franc »," Revue historique 2, no. 638 (2006): 361. [⤒]

- IRP: Institut français du pétrole; BRP: Bureau de recherche de pétrole; S.N. REPAL: Société national de recherche et d'exploitation de pétrole en Algérie; CFPA: Compagnies françaises des pétroles (Algérie). See Saul, "Politique nationale du pétrole," 361. [⤒]

- Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Free Press, 1991), 508. [⤒]

- As Timothy Mitchell has argued, petroleum rose to prominence due to a combination of economic factors and its material properties, which allowed it to be controlled, especially without labor interference, more effectively than coal. See Timothy Mitchell, Carbon Democracy: Political Power in the Age of Oil (London: Verso, 2011). For more about the French energy market, see Robert J. Lieber, "Energy Policies of the Fifth Republic," in The Fifth Republic at Twenty, ed. William G. Andrews and Stanley Hoffmann (Albany: SUNY Press, 1981), 313. [⤒]

- On French coal industry films, see Estelle Caron, "Images de la mine et des mineurs," Les Cahiers de la cinémathèque, Cinéma Ouvrier en France, no. 71 (December 2000): 47-52. [⤒]

- In 1965, the circulation of Paris Match (commonly described as the French equivalent of Life) was somewhere north of one million copies per week, down from about 1.8 million in 1958. See Serge Berstein and Jean-Pierre Rioux, The Pompidou Years, 1969-1974, trans. Christopher Woodall, Cambridge History of Modern France 9 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 199-200. [⤒]

- André Nouschi, La France et le pétrole de 1924 à nos jours (Paris: Picard, 2001), 67. [⤒]

- Alain Beltran, "Compteurs bleus et points rouges: Séduire le consommateur d'énergie dans les années 1960," in Georges Pompidou et la modernité: les tensions de l'innovation, 1962-1974, ed. Pascal Griset (Brussels: Peter Lang, 2006), 101. [⤒]

- Ibid., 103. [⤒]

- Saul, "Politique nationale du pétrole," 366-68. As Samir Saul explains, the state's primary concern was economic: how to trade oil in francs. [⤒]

- I thank Reinhold Martin for directing me to this image. See Le Corbusier, La Ville radieuse: éléments d'une doctrine d'urbanisme pour l'équipement de la civilisation machiniste (Paris: Vincent, Fréal, 1933), 135. [⤒]

- Mitchell, Carbon Democracy. [⤒]

- Martin Heidegger, What Is Called Thinking?, trans. J. Glenn Gray (New York: Harper & Row, 1968), 16. [⤒]

- Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham: Duke University Press, 1993), xii. [⤒]

- Ibid., 102. [⤒]

- Ibid., xi-xii. [⤒]

- Ibid., 101. [⤒]

- Ibid., 102. [⤒]

- Heidegger, What Is Called Thinking?, 16. [⤒]

- See Martin Heidegger, Discourse on Thinking, trans. John M. Anderson and E. Hans Freund (New York: Harper & Row, 1966), 50. Originally published as Martin Heidegger, Gelassenheit (Pfullingen: Verlag Günther Neske, 1959). Cited in Darin Barney, "Pipelines," in Fueling Culture: 101 Words for Energy and Environment, ed. Imre Szeman, Jennifer Wenzel, and Patricia Yaeger (New York: Fordham University Press, 2017), 267. [⤒]

- Heidegger begins the address by reflecting on why a philosopher should speak at such an event at all, reasoning that while anniversary celebrations seemingly engender thinking (as an occasion to "think back"), in fact they had come to embody society's more general "flight from thinking." No real thinking would happen at this event, Heidegger implied; only the thoughtless commemoration of "playing and singing," even of the best music. Recognizing this potential for thoughtlessness offered an opportunity to call for the renewal of the meditative thinking in which Kreutzer's works had taken root. Heidegger, Discourse on Thinking, 44-45. [⤒]

- Ibid., 52. [⤒]

- Edward Dimendberg, "'These Are Not Exercises in Style': Le chant du styrène," October, no. 112 (Spring 2005): 63-88. [⤒]

- "The poster," Savignac wrote, "is a sort of visual scandal. It is not something that is looked at, but one that is seen. . . . Its impression must be instantaneous." Raymond Savignac, "Posters That Shock by Savignac," Graphis, September 1, 1963, 378. Savignac presumably wrote this in French, which appears in the article alongside the English (and German) as: "L'affiche est un scandale visual. On ne la regarde pas, on la voit. . . . Sa lecture doit être instantanée." [⤒]

- Roland Barthes, "Défense d'afficher: A New Cycle of Satirical Works," Graphis, September 1, 1973, 444. [⤒]

- Kaira M. Cabañas, The Myth of Nouveau Réalisme: Art and the Performative in Postwar France (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013), 10. See also Jill Carrick, who notes critic Pierre Restany's role in downplaying these artists' social criticism. Jill Carrick, Nouveau Réalisme, 1960s France, and the Neo-Avant-Garde: Topographies of Chance and Return (Burlington: Ashgate, 2010), 45. [⤒]

- Hannah Feldman, From a Nation Torn: Decolonizing Art and Representation in France, 1945-1962 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), Chapter 4; Carrick, Nouveau Réalisme, 1960s France, and the Neo-Avant-Garde, 68-72. [⤒]

- Matthias Koddenberg, "Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Beyond Fabric," in Christo et Jeanne-Claude: Barrels (Dortmund: Verlag Kettler, 2016), 10. [⤒]

- Ibid., 12. [⤒]

- Ibid., 20. [⤒]

- Ibid., 24; Olivier Kaeppelin, "Interview with Christo," in Christo et Jeanne-Claude: Barrels (Dortmund: Verlag Kettler, 2016), 60. [⤒]

- Catherine E. Clark, "Capturing the Moment, Picturing History: The Liberation of Paris and Photographs," American Historical Review 121, no. 3 (2016): 824-60. [⤒]

- Koddenberg, "Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Beyond Fabric," 24. [⤒]

- Tom McDonough, Beautiful Language of My Century: Reinventing the Language of Contestation in Postwar France, 1945-1968 (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007), 90-94. [⤒]

- McDonough notes only that as they struggled to convince the police not to dismantle it, "Christo and his entourage offered explanations of the wall to the curious, remarking that its construction was occurring — 'not at all coincidentally' — the day after a massive conflagration that destroyed oil tanks in the port of Oran, ten million liters having burned after an OAS attack on the reservoirs of British Petroleum," a fact that was, McDonough writes, "completely coincidental." See Ibid., 93. [⤒]

- Yergin, The Prize, 35; 43. [⤒]

- Koddenberg, "Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Beyond Fabric," 40. [⤒]

- Michael Fried, "Art and Objecthood," Artforum 5, no. 10 (Summer 1967): 12-23; Michael Fried, "Art and Objecthood," in Art and Objecthood: Essays and Reviews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 148-72. [⤒]

- Lawrence Alloway, Christo (New York: Abrams, 1970), vi. [⤒]

- Ibid., vi; David Bourdon, Christo (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1970), 24. [⤒]

- One key exception is Edward Dimendberg's description of the "240 tangible reminders of the petroleum economy" that structured the barricade on the rue Visconti. See also the review of Christo and Jeanne-Claude's more general use of barrels from the 1950s to the 1990s by Marija Cetinić and Jeff Diamanti, who briefly situate the wall in the context of France's hope for Algerian oil. See Dimendberg,"'These Are Not Exercises in Style,'" 88; Marija Cetinić and Jeff Diamanti, "Monumental Oil," American Book Review 33, no. 3 (2012): 5; 29. [⤒]

- Kaeppelin, "Interview with Christo," 76. [⤒]

- Alloway, Christo, v. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Bourdon, Christo, 15. [⤒]

- Brown, Other Things, 41. [⤒]

- Ibid., 51. [⤒]

- "Somehow Jeanne-Claude managed to appease the officers long enough for the artists to be able to shoot some pictures in the dark of the night before taking everything down and driving the barrels back to Gentilly." Koddenberg, "Christo and Jeanne-Claude: Beyond Fabric," 24. [⤒]

- This reading of the barrels squares with Cabañas's argument that Restany "render[ed] the art not only transparent but also politically neutral, insofar as he frame[d] direct appropriation as evidence of a work's total integration to modern technological culture." Pierre Restany, "Christo: le rideau de fer : mercredi 27 juin 1962: presentation unique, rue Visconti, paris 6e, de 21h à 2h." BVAP Christo 4, Bibliothèque Kandinsky, Centre Pompidou, Paris; Cabañas, The Myth of Nouveau Réalisme, 18. [⤒]

- Ragon reviewed the Galerie J show alongside concurrent gallery exhibitions of Asger Jorn, Arrigo Lora-Totino, and Arnaldo Pomodoro. See Michel Ragon, "Nouvelles Défigurations," Arts, July 11, 1962. [⤒]

- Christophe Bonneuil and Stéphane Frioux, "Les « Trente Ravageuses »? L'Impact environnemental et sanitaire des décennies de haute croissance," in Une autre histoire des « Trente Glorieuses » : Modernisation, Contestations et Pollutions dans la France d'après-guerre, ed. Céline Pessis, Sezin Topçu, and Christophe Bonneuil (Paris: Editions de la décourverte, 2013), 41-59. [⤒]

- For an account of the protests' origins, see McAuley, "Low Visibility." [⤒]

- For more on the "social transformations of the past decades" that shaped initial resistance to the fuel tax, see Didier Fassin and Anne-Claire Defossez, "An Improbable Movement? Macron's France and the Rise of the Gilets Jaunes," New Left Review, no. 115 (February 2019): 79-80. [⤒]

- Consider, for instance, France's comparatively heavy reliance on diesel fuel. As Fassin and Defossez note, the French state has long encouraged automobile manufacturers and French consumers to build and buy diesel cars, thereby (among other reasons) providing a market for the Algerian petroleum sourced in Hassi Messaoud, which, as Samir Saul notes, comprised 50% diesel (compared to 33% gas). See Fassin and Defossez, "An Improbable Movement?"; Saul, "Politique nationale du pétrole," 369. See also Paul Mathis, L'énergie, moteur du progrès? 120 clés pour comprendre les énergies (Versailles: Editions Quae, 2014), 115. [⤒]

- Fassin and Defossez, "An Improbable Movement?," 91. [⤒]