Issue 6: Midcentury Design Cultures

Classical Hollywood cinema was a narrative art, a spectacle centered on stars, and an industry producing entertainment for profit. These accounts would be familiar to almost anyone exposed to mainstream movies in the United States, which is to say, just about everyone. Another foundational account is less prominent and intuitive, but equally essential to an understanding of film in the studio era: classical cinema was a spatial and environmental art that situated stories and bodies within a world created in part or entirely on the studio lot. As the veteran art director Rudolph Sternad noted in 1952, "movies are 90 percent physical," and for that reason the production process would seek elegant, cost-effective solutions to a broad range of "physical problems" at the core of the production process.1 The "painstaking efforts" described by Sternad were primarily focused on the design and fabrication of space: a building's exterior architecture and interior decoration, the facades lining a city street and their extension toward the horizon, the quasi-natural landscapes with mountains and prairies rendered in plaster and paint, and countless other mainstays of cinematic world creation and art department tradecraft.2 Architectural design remains one of the fundamental acts of film production in the digital age, though the tools would, of course, be unrecognizable to anyone schooled in the ways of the old Hollywood studios. Midcentury architects and designers would be equally stunned by the "workflow" of their counterparts today, given the crucial role of computational processes in what used to be a primarily manual art.3 Writing in 1986, Robin Evans characterized architecture as a discipline haunted by the gap between design and construction because the designer creates with pencil and paper rather than wood or steel, "never working directly with the object of their thought, always working through some intervening medium, almost always the drawing."4 That displacement remains a defining feature of architecture, though now the screen and keyboard intervene between the conceptual stage and its execution, and cinematic design, which often recombines material and digital objects or spaces layered together to create a virtual space with no physical counterpart in the studio or real world. In the old days both architects and filmmakers worked with their hands, and now, after the "death of drawing" and the rise of digital design tools, they work increasingly with computers.5 This essay is about the many links between architecture and cinema in the past, and the even more profound connection between them in the digital age. While the architectural design process involves the manipulation of moving images on a screen, the production of a major studio film often entails the creation of spaces that exist only as digital simulations. Designers in both domains use variations of the same software supplied by a small number of companies specializing in design computing. Cinema in the digital age is still a spatial and environmental art, but world creation in the movies often begins and ends on a screen, bypassing or downplaying the previously fundamental act of construction on the sound stage. Despite classical Hollywood's reputation as a merchant of dreams, filmmakers inevitably confronted material constraints within the confines of the studio, as their creativity encountered the limitations of an art form that was "90 percent physical." In cinema today, for the first time, anything that can be designed can be exhibited on a screen because it has been created on a screen in the first place.6 This reliance on digital technology in the imagination of cinematic worlds has changed the film industry as profoundly as it has affected other design professions, and in the essay below, I will explore the implications of this convergence of production design and architecture by focusing on what Evans calls a "manner of working," by approaching these arts and crafts through their common tools and practices. Adapting the work of Fredric Jameson for the era of computer-generated imagery, I also search for signatures of the digital in the architecture and moving pictures of the twenty-first century, for the traces of computational design left behind on the screen or structure. Guided by cinematic traditions developed in the mechanical age and tantalized by the possibilities of digital technology, contemporary filmmakers work on the threshold between two historical eras and their distinctive approaches to the design and fabrication of space. This essay will follow them across that threshold, as the camera passes, in an exhilarating and troubling moment, between the remains of a filmic world inherited from the twentieth century and the digital futures being designed today.

The Architectural Department

The practices of architecture and film production have always been intertwined. As Brian R. Jacobson observes, the nascent movie industry of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries developed in tandem with dedicated studio architecture because the first cameras and film stock could generate usable images only under particular environmental conditions.7 Edison's Black Maria was the first purpose-built film studio, and its technological affordances and aesthetic possibilities — its black tar-papered background and overhead lighting provided by a retractable roof — shaped the films created on and for that stage.8 As film studios expanded at the turn of the twentieth century, they opened up new possibilities for the depiction of artificial settings and the development of the crafts of cinematic set design and scene painting. By combining this modern mechanical medium and the venerable traditions of architecture and set design, cinema became an art of world creation, in addition to its better-known functions as a vehicle for the mass dissemination of narrative entertainment or recorded performance.

As those sets grew in scale and complexity, eventually encompassing simulated city streets and small towns on the back lot, the standard professional training for the art director (or "technical advisor," as they were initially known) shifted from theatrical scene painting to formal schooling or apprenticeship in architecture.9 In the stock response sent to aspiring art directors seeking employment in his office at MGM, Cedric Gibbons, the studio's longtime Supervising Art Director, wrote: "To begin with the Art Department of a motion picture studio should really be called the Architectural Department since our work is designing motion picture sets through the medium of architecture."10 He added that his staff required a level of technical expertise that would prevent artists and designers in other fields from making the transition to the studios: "Our work here is highly specialized and our people are all graduate architects or the equivalent."11 While Gibbons lacked that formal education in architecture himself, he designed several high-profile houses, including the one he shared with his wife, Dolores Del Rio, a structure that subsequent critics have recognized as one of the prime examples of "LA modern."12 A large cohort of art directors who came of age during the Depression trained as architects but faced the choice between unemployment in their chosen profession and temporary refuge in the movie business; while real-world building projects were few and far between, the studios continued to churn out entertainment and a steady supply of sets and facades. Others viewed art direction as a more experimental, capacious field than the everyday practice of architecture and regarded their most inspired designs as a popular counterpart to modernist or avant-garde art.13 Many of them would work in the studio system for decades. The look of studio-era Hollywood cinema was largely the creation of those converted architects, whose standing sets were permanent fixtures on the lot and whose designs became influential within both the movie industry and the commercial design sectors operating under the enormous gravitational pull of Hollywood style and glamour. These supervising art directors and the "Architectural Department" continued to command a large share of studio resources throughout the classical era, with set design and construction usually the second- or third-largest line item on the production budget, after star salaries and potentially the acquisition of intellectual property, including popular novels, plays, and songbooks. To a significant but habitually underappreciated degree, the finances, labor, and energy of the Hollywood dream factories were devoted to the design and construction of settings that would appear on camera as the background to a story or, as in the musicals from the 1930s to the 1950s, a spectacle in their own right. Realizing that vision required specialists who could think and design like architects and a large team of tradespeople capable of building out those plans at an astonishing pace.

While the periodization of post-classical Hollywood usually focuses on industrial factors — the decline of the studio system in the 1950s and 1960s, the rise of independent production in New Hollywood, and the impact of television and other entertainment in competition with cinema — this new era could also be characterized by its rapidly changing relationship to architecture. One of the most radical features of the new cinema was a shifting balance between location shooting and set construction on the studio lot.14 Filmmakers began to prioritize the authenticity of real-world environments over the creative and managerial control of studio settings engineered under the gaze of a nearby producer. While studio executives previously emphasized the disadvantages of filming in a faraway location subject to the disruptions of social upheaval and the whims of nature, a new calculus ascribed much greater value to the intimate connection between cinema and reality made possible by taking the production out of the sound stage and into the streets. This tendency was evident in both art cinema influenced by the global new waves of the 1950s and 1960s, including the work of John Cassavetes or Melvin Van Peebles, and major studio productions like Bullitt (Warner Bros.-Seven Arts; Peter Yates, 1968) or The French Connection (Fox; William Friedkin, 1971). Grand in scale and accurate in every detail, the world outside the sound stage was reimagined as a set conterminous with reality.

That fascination with location shooting has dampened since the early years of New Hollywood, and filmmakers have returned to a sound stage undergoing a revolution due to the influence of computational design and the proliferation of visual effects. Architects and production designers have continued to deploy overlapping sets of skills and tools, but that toolbox has changed dramatically since the classical Hollywood era. Hand drawing and physical modeling were no longer default methods in the design professions in the late twentieth century, a tendency that has accelerated since the "second digital turn" in the twenty-first.15 If an earlier generation of digital design began with sketches or models before duplicating them on a computer, the next generation would explore the unique affordances of digital technology to create architectural or cinematic spaces unimaginable within the notational constraints of Cartesian geometry and the spatial and logistical limitations of the classical sound stage. If cinema has always been a phenomenon of architecture, those fields would remain intertwined in the digital age, but only because both cinematic and architectural design have been transformed by digital technology, especially in the big-budget architectural showpiece and the cinematic blockbuster. Both practices have long since entered the era of Computer-Aided Design (CAD) and Computer-Generated Imagery (CGI), the overlapping industrial terms that foreground the role of digital technology in contemporary creative industries. As Greg Lynn suggests, these transitions to digital production in architecture and cinema were staggered by about a decade rather than simultaneous: the morphing effects evident in 1980s blockbusters like The Terminator (James Cameron, 1984) depended on graphics technology that architects would adopt only in the 1990s, in a series of radical experiments with curvilinear forms usually associated with Frank Gehry.16 But after the widespread conversion to digital production processes under the influence of parametric design and Building Information Modeling (BIM) in the new millennium, those computational tools now generate shapes that respond to numerical values and relations, a data set that incorporates a wide range of financial, engineering, environmental, and other factors before it yields a visual or sculptural object with particular aesthetic features.17 What used to be the distinctive act of architectural design — finding a form, usually sketch by sketch, model by model — has been deferred until later in the process and partially delegated to algorithmic functions. A similar phenomenon is currently taking place in cinema, though in a scattered and sporadic fashion, suggesting that the design professions have now outstripped filmmakers in their embrace of computational forms. A second digital revolution in cinema would move beyond the search for a more spectacular or realistic variation on already familiar effects and instead embrace the role of technology in the process of form-finding, but with the potential for speculation and experimentation that has always been the hallmark or (often unrealized) promise of virtual worlds. This computational cinema would, in other words, begin by recognizing its longstanding and increasingly profound connections to architectural design. A design-centered investigation of digital cinema would focus not only on new cameras, storage technology, and special effects software — for those devices can be used to replicate a classical style — but also on the traces of computer-aided design left behind everywhere on the screen by the newest incarnations of the "architectural department."

CGI Architecture and CAD Cinema

While the otherworldly scale of computer-generated spaces and simulated crowds are the most obvious markers of the transition to digital cinema, camera movement is another key index of the interconnections between contemporary cinema and digital design, especially the modes of extreme camera fluidity that have proliferated over the past two decades.18 These almost impossibly mobile cameras trace a boundary between the aesthetic and social imagination of film and the computational imagination of the twenty-first century. In the studio era, cinematography, especially camera movement, was a phenomenon of infrastructure and therefore of spatial and logistical limits. A cinematic world must be designed and built with movement in mind, especially the passage of people and cameras through a scene. The most prominent examples of the infrastructural demands of a moving camera are the tracks, dollies, and cranes that represent the most obvious analogies to the train tracks, highways, and airports that usually come to mind when we think of infrastructure. But in the heyday of classical cinema, camera movement and the design and construction of sets were intimately intermingled. A scene involving extensive camera movement would usually require expansive (and therefore expensive) sets built out to fill the roving frame, and that movement was only possible because of the decorated interiors, walls, roads, sidewalks, and streetlamps constructed on the sound stage or studio lot. Given that semi-permanent sets were continually reused and recycled at the major studios and that existing designs and materials were adapted for new purposes, much of what we see on the screen lies in a nebulous gray area between architecture and infrastructure, between designs constructed with particular programs in mind and what Paul Edwards calls the "invisible background," the "large, force-amplifying systems" that endure beyond the lifespan of individual buildings and form the interstitial spaces between them.19 Important recent scholarship has laid bare the infrastructural requirements of cinema and the media industries, including Jacobson's essential book, Studios Before the System, and the equally compelling work by Lisa Parks on satellites and Nicole Starosielski on undersea cables.20 More recently still, John Durham Peters has reframed media as an "infrastructure of being" and called for a new mode of materialist philosophy dubbed "infrastructuralism," a tongue-in-cheek replacement for the archaic structuralisms and post-structuralisms of the previous century.21 In each of these cases, the research focuses on not only the content or meaning of the information communicated through those networks but also the substrate that makes particular forms of transmission possible and both channels and limits that communication. Cinematic design would be the process that deploys then conceals the infrastructural underpinnings of cinema and, usually in combination with a narrative, relegates that system of production and a team of designers and builders to the background again, leaving us with a seemingly evanescent product: moving pictures on a screen. Because of its profound relationship to and dependence on infrastructure, camera movement allows us to see traces of the system that would otherwise remain the "invisible background" of the image. This remains true in digital cinema, where once again design is the interface between the cinematic form manifested in camera movement and the technological infrastructure underlying it.

Because architects and digital media designers rely on similar technical training and software, architecture and cinematic production design now share an overlapping, often indistinguishable infrastructure. The design process for digital effects usually involves multiple stages where virtual objects and structures are created in architectural and product design applications then imported to 3D animation software, where they become particularized features of a mobile and manipulable space, architectural design in a cinematic world. In architectural cinematography, or the deployment of virtual cameras in design projects to simulate movement through a proposed structure, camera movement and design are also intimately intertwined. In these navigable digital prototypes, we see the cinematic imagination at the core of contemporary architectural design and modeling, the desire to move beyond still images or models and previsualize the total experience of a space. All of these related activities — the creation of objects and spaces for cinema, and the introduction of motion into architectural plans — depend on the vital contributions of designers whose training and workflow revolve around CAD and animation software, especially the nearly ubiquitous Autodesk products found in most architectural firms (including AutoCAD, Revit, and many others) and effects studios (Maya, 3ds Max, Arnold, Mudbox, and, again, many others).22 In 2018, for example, Autodesk software was used on all five films nominated for the Academy Award for best visual effects, and key contributors to Autodesk products are regularly honored with Oscars at the scientific and technical ceremony. But the company got its start as a pioneer in the development of digital tools for the practice of architecture, beginning with the long-running AutoCAD Architecture product introduced in 1982. More recently, it emerged as a leader in the rapid shift towards parametric design and Building Information Modeling through its Revit line, which organizes the design process around data as well as form.

A twenty-first century CAD or CGI universe is designed for the roving eye. Carlos Calderon and co-authors call this virtual observer an "architectural cinematographer," which refers to both a specific tool invented by that group and a more general problem faced by architects who must choreograph movement in provisional designs.23 Calderon presents three basic alternatives open to the designer: they can model their simulations after a first-person shooter and offer a minimally mediated experience of the setting; they can mimic a follow shot, as though accompanying a person walking through the scene, though a step or two behind; or, finally, they can simulate a classically constructed film, with editing and a variety of camera angles, replacing a phenomenological paradigm with cinema's most familiar mode of mediation.24 Underlying these questions is a more general concern: when the virtual camera moves or changes perspective, what conceptual system makes sense of those movements or transitions? Should the designer be "seeing architecture with a filmmaker's eyes," as Aron Temkin suggests, conceiving of both the model and the structure from the perspective of a mobile subject?25 Or can architects resist this cinematic turn and continue to rely on the discipline's traditional systems of notation and representation, including the scale model, foreshortened drawings that evoke a three-dimensional space, or, on the most abstract level, technical blueprints? In most cases a multimodal approach is necessary because different methods are suited to specific tasks or situations, but what matters is the inescapable reality that mobility and a cinematographic gaze are now basic capabilities built into the software used to produce architectural designs. If anything that can be designed can be rendered on a screen in a navigable, interactive form, cinema remains one of the key paradigms for organizing the passage through space and translating the experience of movement into an intelligible visual form. To design with digital tools is to think cinematically about objects and environments.

The convergence of architecture and cinema is apparent not only in design or film studios but also in the industrial strategy of the major producers of the software they deploy, especially the dominant player in this sector, Autodesk. A 2020 promotional video for Revit presents architects at their workstations while animated models derived from their designs sprout up through the desks or drop from the ceilings. This marketing campaign imagines a fantastic workspace in which the gap between design and construction — the defining feature of architectural labor, according to Robin Evans — is minimized. Buildings become vital, mobile objects within the mise-en-scène of the studio. The aspiration of the product, at least in this idealized form, is to enable these seamless transitions from the space of design to the fabrication of space or between architecture and moving pictures, with buildings envisioned as hybrids of the concrete and the cinematic, as material objects springing suddenly into motion. Autodesk University, the company-sponsored series of industry talks and training programs for its customers, regularly features courses that blur the lines between architecture and cinema, including, for example, "Aerial Cinematography and CGI for Architecture, Advertising, and Film" (2015) and "The Making of a Virtual Film for Architecture and Real Estate" (2016).26 Autodesk products helped design Avatar (2009), Frozen (2013), and versions of the video game Grand Theft Auto, alongside its primary business focused on design software for architects and engineers. The synergy between cinema and architecture is evident in these complementary product lines and the rapidly vanishing border between them. Capitalizing on this close alliance between its animation and architectural products, and hoping to profit from the widespread "pivot to video" in the social media sector, Autodesk ventured into the social video market in 2012 with the acquisition of the startup Socialcam, expanding from its primarily professional clientele into more consumer-oriented applications.27 This focus on the interdisciplinary nature of its products is reflected in a company slogan — "Make Anything" — which emphasizes flexibility rather than specialization and appeals to the burgeoning maker movement, the large market that falls somewhere in between design professionals and everyday consumers. While the technology and the concepts of "social media" and "makers" are relatively new, all of these product lines could be situated within the long history of interaction between moving images and design, as new variations on an old and familiar theme. Former Autodesk CEO Carl Bass remarked that "everything out there that's not natural, one of our customers made," and while that boosterish tone may exaggerate the impact of a single company, it does reflect the increasingly important role of design software across the spectrum of cultural and industrial production.28 The industrial arts of cinema and architecture have been absorbed into what Herb Simon calls the "sciences of the artificial" whose common feature is the reorganization of the environment through design.29

If animation tools revolutionized architectural design, architectural design technology has in turn transformed production design in cinema. Cinema and architecture have come full circle, as the most popular film genres have migrated away from the photographic origins of the medium and its fundamental link to the existing built environment or specially constructed set. Instead filmmakers have become architects and city builders on an unprecedented scale, creators of a digital substitute for reality or a world without any analog outside the theater or in the realm of photography, traditionally conceived. Both these digital tools and the universe constructed in their image invent new categories of space and ways of seeing through innovative modes of cinematography. Jameson famously searched for "signatures of the visible" in one of his key studies of cinema in the postmodern age, with the ambitious goal of writing a materialist history of the hyperstylized cinema of the late twentieth century.30 A twenty-first century counterpart of Jameson's project would identify signatures of the digital in the moments when a film projects a CGI world that would have been unrealizable in prior regimes of cinematic production, operating under logistically and financially constrained conditions on the studio lot. We can find those traces of digital design in most major studio releases today.

One of the most stunning recent examples of this phenomenon is found in the opening scene from Hugo (2011), an Academy Award winner for Best Cinematography (Robert Richardson) and Best Visual Effects (Robert Legato, Ben Grossmann, Alex Henning, and Joss Williams). Despite its focus on the wondrous early years of French film, Hugo is also a virtuoso display of the possibilities of CGI filmmaking or, more precisely, a cinema conceived at the intersection of film history and the new design and effects software used to create space and operate a virtual camera to move through it. Scorsese has always been a cinephile's filmmaker, a product of the film school generation of the 1970s and the New York counterpart of George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Spielberg in California. While that cinephilia is usually associated with celluloid and Scorsese is an outspoken advocate (and generous sponsor) of film preservation, he has not shied away from adopting digital technology in his own production practices. The Wolf of Wall Street (2013) was the first major Hollywood production distributed exclusively as a Digital Cinema Package, a major milestone on the path to near-total digitalization of film distribution and exhibition. In Hugo he opens a nostalgic account of the early days of the medium and the career of Méliès with a tour de force digital recreation of Paris and a swooping, vertiginous camera movement through an at once historical and animated world.

The film begins with an image of the slowly turning mechanism of a clock, the wheels clicking second by second and rotating around their pinions, before dissolving into an overhead shot of the city of Paris, the center of the spinning wheel replaced by the traffic circle around the Arc de Triomphe. The allusion to a clockwork universe is essential here, as the film both gestures towards the mechanical past of early cameras and projectors — with their gears and cranks, shutters and bobbins — and remakes it in a digital format (figure 1). This is the machine age revisited not through the technologies of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that feature so prominently in the film but through Autodesk's 3ds Max, Maya, and MotionBuilder, and Dassault's SolidWorks. What follows would have been unthinkable within a clockwork, mechanical conception of cinema, as the camera floats above the city, panning right to reveal the Eiffel Tower; then the film cuts to another vista, essentially a detail from the first, centered on a train station where most of the action takes place (figure 2). In a digital variation on the helicopter shot, the virtual camera then plummets towards the ground while hurtling forward to the gaping entrance to the train shed. It passes beneath the overall roof, flying at breakneck speed, but no longer in the open air, as it navigates a narrow path along the platform between two trains, dodging passengers along the way (figure 3). The film will later feature a screening of the Lumière Brothers's Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1895), the source of the apocryphal but immensely influential story of spectators fleeing the theater at the sight of a train apparently crashing through the screen. Scorsese then offers a contemporary variation on that scene in CGI and, in certain exhibition venues, 3D. Despite the picture's legendary status in film history, the immobile camera marks the Lumière Arrival as a relic from the past, while Hugo explores new forms of exhilarating and unsettling spectatorial experience based on the freedom of movement possible in the CGI-enhanced world in Hugo, as designed by Legato and his team. One of the most visible consequences of the shift toward digital filmmaking practices has been the normalization of a vertiginous aesthetic, especially the plunging camera featured in Hugo, a device that takes us from the most expansive to the most intimate view in about a minute, stopping finally on a close-up of the title character's eye (figure 4). At a certain point in this opening sequence, the digital substrate of the image is revealed not only through details that don't quite "look real" on closer inspection (the insufficiently detailed human faces along the train tracks, for example) but also through movements that are too fast, too dynamic, and would be too threatening to the stars, crew, and extras (and, of course, the insurance company responsible for any damages or liability) to belong to the film age.31 What sets this digitally created opening sequence apart from a film is not the medium per se but the excessive, exuberant motion made possible by the affordances of digital design technology and virtual cinematography. This movement bears the signatures of the design process that made it possible in the first place.

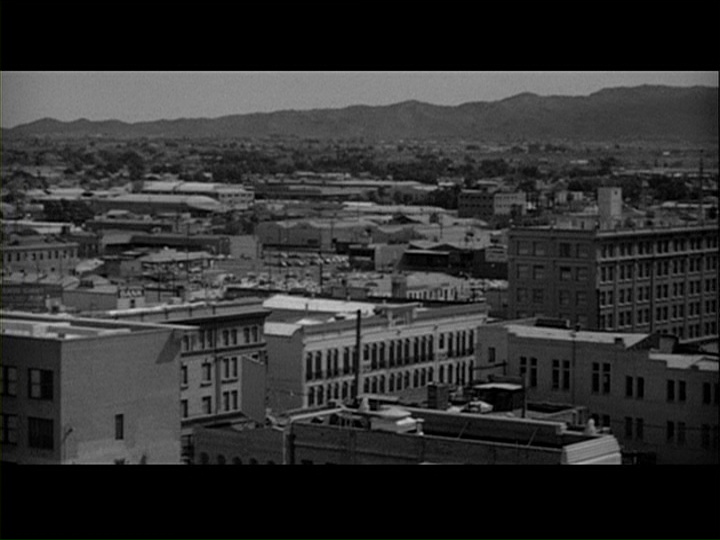

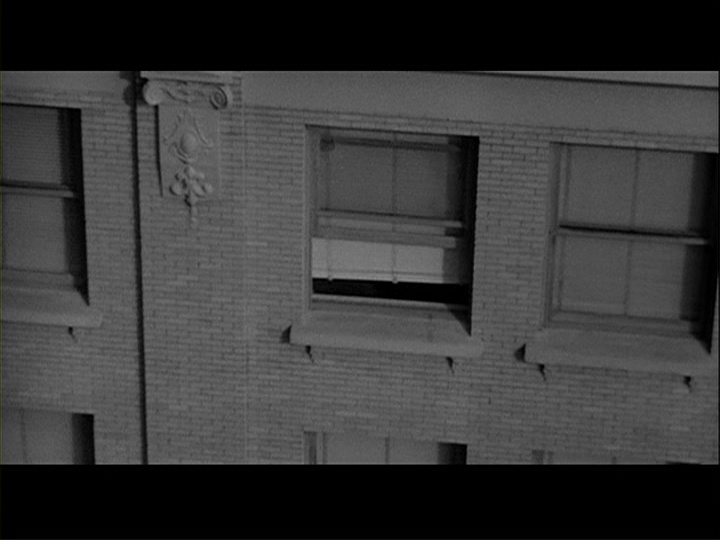

The intensity of this motion is most apparent when compared with the opening sequence of Psycho (1960), which follows a very similar trajectory through space, though on a much smaller geographic scale and with more tentative, restrained, irregular movements. Imagine graphing the path of Hitchcock and Director of Photography John L. Russell's virtuoso camera movements along the x, y, and z axes. The resulting curve would be remarkably similar to the one traced at the beginning of Hugo: a city viewed from above, a jog to the right, a relatively rapid dive forward and down towards a landmark building, where the story will begin. What we see in Psycho is a series of bold camera movements and optical zooms that nonetheless seem hesitant in comparison with the assertion of creative and computational power on display in Hugo. Between the key points on this itinerary — when the camera establishes Phoenix as our location, when it zeroes in on the old Jefferson Hotel, and when it finally stops with the bodies of the two stars forming their own horizontal and vertical axes on the screen — the camera pans unsteadily and zooms forward in fits and starts (figures 5 and 6). Then the film dissolves awkwardly between two camera positions, and, most remarkably, inserts a jump cut that reveals the mismatch between the tone and framing of the façade of the building in Phoenix and its studio replica (figures 7 and 8). The obvious difference between the spaces shown before and after the cut reminds us that the film age was marked as much by failures of photorealist fidelity and continuity as by the more famous illusion of reality and that those failures often manifest themselves in the realm of design. This somewhat jittery camerawork and jagged editing, far from offering a smooth introduction to the story world, instead echo the fragmented language on screen during the credit sequence and foreshadow the unsettling, frenzied montage in the shower sequence to follow. At times Hitchcock swoops in from above with something like the omniscient perspective on display at the beginning of Hugo, but never with the freedom of movement, the seeming omnipotence of Scorsese's hybrid camera that shifts almost imperceptibly between virtual and practical worlds as it leaves the train tracks behind. In Hitchcock, the moving camera never bestows on the spectator the type of privileged vantage point accessible in later films through digital technology; instead the view changes almost haphazardly and cruelly, a reminder of the eternal limitations of an embodied subject position and the infrastructural unconscious glimpsed at the moment of the jump cut. As in Hugo the culmination of all this movement is a moment of intimacy, but the spectator is clearly an unwelcome presence at a scene viewed from a seemingly haphazard angle (figure 9).

Hitchcock's most formally experimental films of the 1940s and 1950s, Rope (1948) and Rear Window (1954), demonstrate the practical limits of camera movement in the analog age. An intricately planned and realized infrastructure supports both the balletic choreography of the camera in Rope and the opposite extreme, a narrative and style premised on immobility, in Rear Window. In both cases movement becomes a limit case in which the exploratory camera is associated with human curiosity and the will to knowledge and power. But when the camera begins to travel, implicating itself in the scene, immersing itself in the world, the result is a catastrophic encounter with mortality rather than the exhilarating rush of speed and energy we experience in a film like Hugo and its many counterparts in contemporary digital cinema. When the camera moves, it not only reveals a visible world that once existed outside the frame or otherwise out of view, it depends on an infrastructure that makes mobility possible: cranes and tracks for Hitchcock and Russell; and in the CGI era, the software necessary to simulate the image of a city and the processing power to run the dozens of algorithms that produce abundant detail in a constantly changing frame. When we think about the signature effects of the contemporary blockbuster, we are confronting large-scale design problems that studio-era cinema — confined to the sound stage or back lot, opening onto a broader landscape only through unchanging painted backdrops and the occasional location footage taken by a second unit — did everything in its power to avoid.

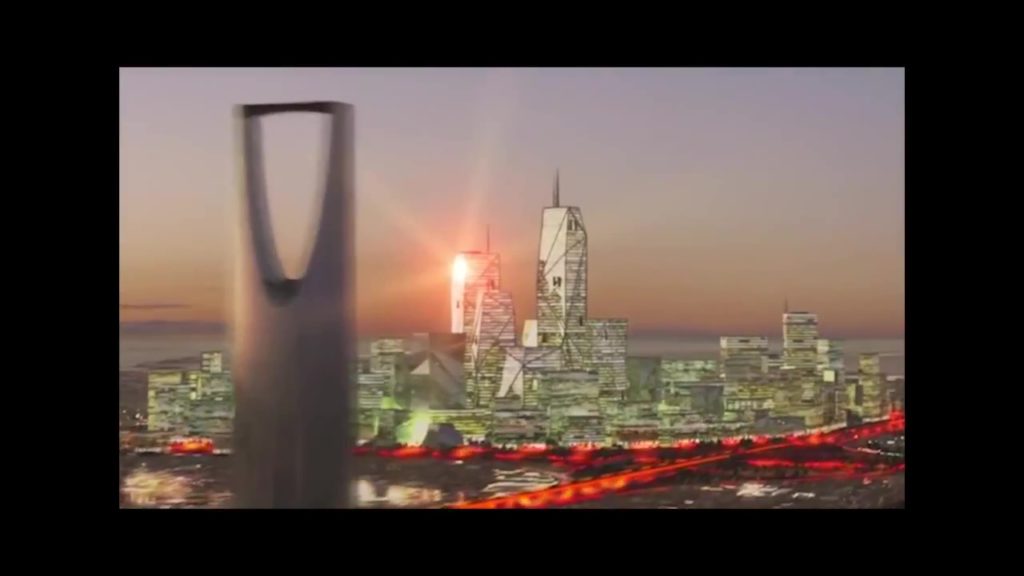

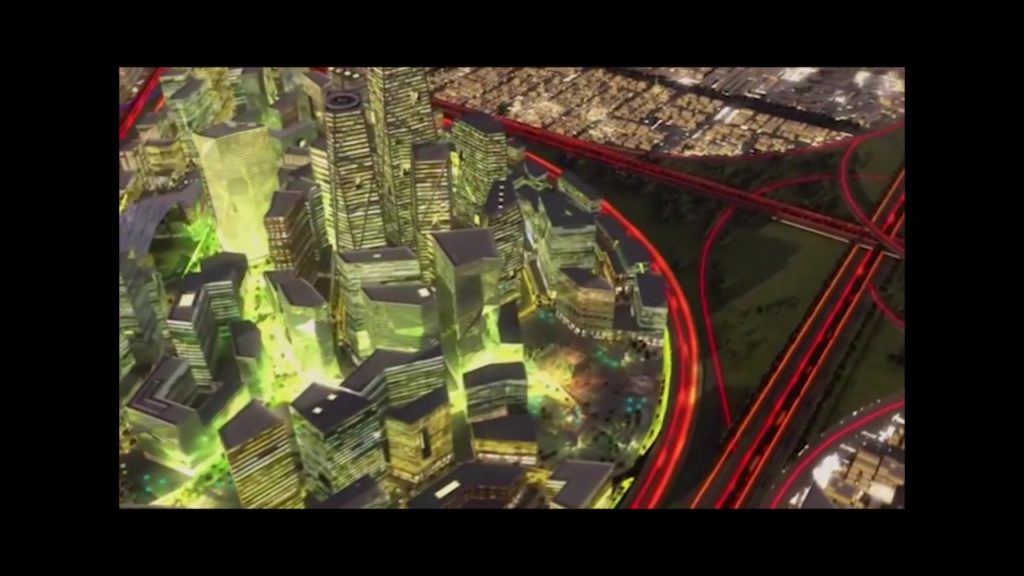

The graceful camera movements on display in Hugo are ubiquitous in contemporary cinema, and with the more widespread dissemination of design/CGI software and increased computing power, a degree of movement that would have been inconceivable in the twentieth century is possible not only in big-budget Hollywood blockbusters but also in avant-garde video arts, as well as online advertisements and other forms of "useful cinema."32 Chris Marker's Ouvroir (2009), the film version of his Second Life environment, begins with an aerial shot of his individualized virtual space and a plunging camera movement that abruptly ends, as, in a gesture typical of Marker's lifelong interests, an animated page turns and Guillaume the cat leads the viewer into a screening room, the intrusion of old media (and cats) into a new media universe (figures 10-11). A more commercially oriented genre produced at the cinema/design nexus and organized around this rushing and plummeting "fly-through" camerawork is the urban promotional video created by teams of architects and filmmakers (e.g., LOISTL Vision of Vienna) and studied and curated by the architect and urban theorist Keller Easterling. In Extrastatecraft, Easterling describes a new category of extraterritorial space produced in the thousands of export-processing zones, free trade territories, and special economic zones established since the 1960s and under rapid development around the world in the age of globalization, from the United States and Mexico to Europe, from Azerbaijan to Tanzania, from Dubai to China. Underlying these models is what she calls "infrastructure space," a concept that refers not only to roads, pipes, and wires but also to the "shared standards and ideas," the "repeatable formulas," "the rules governing the space of everyday life."33 The designer of infrastructure space creates environments with a particular "disposition" — a range of social and political potentials that govern human interaction and the relationship between people and their surroundings — and it therefore operates as "spatial software."34 What these spaces and their promotional videos share in common is a desire for a "clean slate" in the pursuit of economic development without the baggage of national tax schemes and legal structures, and a shared visual strategy as they imagine and realize momentarily, if only in images, that speculative world.35 And Easterling notes the prominence of a particular cinematic device in the dozens of videos created to advertise these spaces before their actual construction (and in the case of abandoned projects, in lieu of the buildings and cities themselves). In the paradigmatic case, a virtual camera reveals a panoramic bird's-eye or satellite view of a speculative urban space then swoops down to the level of the streets and buildings that will, if all goes according to plan, transition from design to reality.36 The most literal connection between these videos and infrastructure is that they often contain at least one moment when the vestigial part of the spectator that lingers on from the film age half-believes that the helicopter and the camera are going to crash into a bridge, a sentiment that, when we regain our bearings and become proper digital spectators again, is more accurately reinterpreted as impressive virtual cinematography deftly maneuvering towards a merely digital bridge (figures 12-15). Those moments of vertiginous camerawork and fleeting danger aside, the most noticeable stylistic or aesthetic feature of these videos is the fact that the camera almost never stops moving. While some of the soundtracks feature unremarkable commentary or a musical score, others matter-of-factly recite a list of the accoutrements demanded by the one percent and high government officials who are the target audience of these short films, from berths for a yacht to helipads. Incessant movement, a single selection from among the large repertoire of filmmaking techniques, has become the privileged strategy for representing these new geopolitical environments while they remain in the realm of conceptual model and unrealized design.

What is the relationship between this extreme camera movement and these speculative spaces that combine the design capabilities of new media and a dynamic sensibility cultivated in the digital age? The most obvious answer is that the filmmakers responsible for these videos are merely deploying the tools in the modeling and animation software at their disposal or that they are borrowing the filmmaking style of hyper-kinetic blockbusters from the past two decades that set the professional standard for videomakers in other domains, including architecture and design. The signature of these design tools remains visible in the final product because, as Mario Carpo suggests, "most digitally designed or manufactured objects can reveal their software bloodline to educated observers," just as film critics can identify stylistic or generic influences on a filmmaker and audiences can recognize on the screen where the bulk of the blockbuster's budget was spent.37 To watch a video that unfolds like an exercise in perpetual motion is to watch the design software as well as the ostensible subject on display. But as Kostas Terzidis argues in his essay on "Algorithmic Form," "by unknowingly converting to the constraints of a particular computer application's style, one runs the risk of being associated not with the cutting-edge research, but with a mannerism of 'high-tech' style," a phenomenon most evident in the 1990s, when architects experimented with complex topologies made possible only with the advent of digital design tools.38 In video production, these elaborate camera movements on display today, these spiraling maneuvers executed in virtual space, are the cinematic equivalents of the folds and eventually the "Blobs" that Greg Lynn described in the 1990s and that exerted a profound influence on cutting-edge architectural design over the next decade.39 In Animate Form, Lynn argues that the dominant model of movement in architecture is usually cinematic, with cinema defined as a "multiplication and sequencing of static snapshots," but he also stresses the limitations of this analogy because architecture functions only as the still frame where movement takes place instead of an animate, vibrant body in itself. He suggests that the goal of architecture in the digital age is to create animated structures characterized by the "co-presence of motion and force," with CAD and parametric design software viewed as an integral component of this newly cinematic architecture, as a source of their potential vitality.40 He writes in conclusion, "If there is a single concept that must be engaged due to the proliferation of topological shapes and computer-aided tools, it is that in their structure as abstract machines, these technologies are animate."41 One function of the incessantly mobile camera in these urban and architectural design videos is to lend prestige to their projects by associating them with the cultural cachet of the box-office hit, but, perhaps more importantly, this virtual camerawork is also an exercise in animation through technology. Sometimes complex and elegant, sometimes ostentatious and gratuitous, these camera movements through space have emerged at the interstices of moving pictures and design, and they have become a hallmark of a new era of vitality in architecture and folding in cinema.

One major drawback of this tendency toward increasingly rapid camera movement in virtual space is the fact that speculative videos often obscure or blur the project that they are supposed to be marketing, making it impossible to distinguish the between the aims of the developers or government agencies interested in selling a particular real-world project and the often contradictory aesthetic effects organized around the generalized experience of vertiginous motion. At times it's difficult to determine whether the excessive movement contributes to an almost magical illusion of animation or undermines the more practical ambitions of the clients. But this variation on a theme of motion blur may be a necessary feature of these video productions precisely because of the speculative nature of the projects, because there are very few historical or current-day analogs to cite as proof of concept or evidence of feasibility, aside from Shenzhen, Hainan, and the other zones created in the ongoing Chinese experiment. The camera movement at once reveals the scope and scale of the project's ambition and its abstract quality; it highlights that fact that we are looking at what designers and those versed in contemporary business-speak call "design thinking" rather than the cinematic universe predicated on the logic of the photographic image. In a quick gloss on the term "design thinking," John Chris Jones emphasizes the temporal distinction between the orientation and mindset of the designer and the scientist. "The main point of difference is that of timing," he writes, "Both artists and scientists operate on the physical world as it exists in the present (whether it is real or symbolic), while mathematicians operate on abstract relationships that are independent of historical time. Designers, on the other hand, are forever bound to treat as real that which exists only in an imagined future and have to specify ways in which the foreseen thing can be made to exist."42 The camera movements on display in these promotional videos are a symptom of the transition to an underlying logic of design thinking and away from the photographic sensibility that André Bazin described as a revelation in the present rather than a future-oriented transformation of reality.43 On the one hand, the video suggests that a speculative space can undergo a transition from design to actualization, that this patchwork of territories can be stitched together into a new world system, that the areas on the map traversed only by lines will someday be incorporated into an emerging network of special economic zones. On the other hand, the camera movement reveals the conjectural, risky gambit underlying these projects. As Easterling underscores, this type of experimentation on the scale of the city is fraught with danger, as these free trade zones are predicated on the assumption that the current model of global capitalism is economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable.44 What this camera movement whizzes past is a cityscape and a countryside without infrastructure, both in the physical sense of roads, communications systems, sewers, etc., the "naturalized background" of modernity in the words of Edwards, and in the metaphorical sense emphasized by Easterling: a set of communal standards and social relations necessary for the inhabitants of these spaces to situate themselves outside the national framework, whose margins they barely inhabit, and within a global system they glimpse from afar.45

This camera movement is no longer experiential, a paradigm that places the viewer in the position of characters that the director examines and follows. That concept of movement assumed a complex web of social relations that the slowly tracking camera would demonstrate as it traced purposeful patterns across the set. That model of camera movement itself required both the physical infrastructure of the studio setting, the electricity and cables and tracks that made this mobility possible, and a metaphorical sense of shared experience and belonging that allowed to audience to imagine the camera as a plausible stand-in for a human subject tracing similar lines and establishing various attachments and elective affinities. It also, as Daniel Morgan argues in his essay on Max Ophuls, explores "the nature of the moral claims and demands that characters make but which are missed or denied by the world they inhabit."46 What we have in these promotional videos is instead camera movement produced in the absence of and substituting for those material and social connections, as well as the often idealized and unrealized moral claims at the core of a classical system. The virtual cinematography provides a spectacular attraction that we can't turn away from and warns us not to examine the scene too closely, to suspend a vestigial realist sensibility that haunts this borderland between cinema and design.

In the age of digital design and virtual camera movement, we are witnessing the transition of film conventions into a formal and ideological infrastructure that underlies digital design, just as computer-aided design becomes a foundational infrastructure of cinema. As Edwards argues in "Infrastructure and Modernity," what's most remarkable about technology is not when it calls attention to itself with a new product release or revolutionary invention but the fact that "most technology is not salient for most people, most of the time."47 While "emerging markets in high-tech goods probably account for a great deal of technodiscourse," "inventions of far larger historical significance, such as ceramics, screws, basketry, and paper, no longer even count as 'technology.'"48 "Television, indoor plumbing, and ordinary telephony — yesteryear's Next Big Things — draw little but yawns."49 But, he argues, these inventions are usually not superseded and they rarely disappear; instead they become what he calls the "naturalized background" of more contemporary technology.50 Cinema is now a key component of the infrastructure, the "naturalized background" of digital media and design, even as new technologies offer a different range of affordances and gesture beyond that residual cinematic mentality. If studio-era cinema was defined by a delicate balance between architecture and photography, we inhabit a historical moment when major blockbusters combine live-action photography and CGI within the same image, when effects houses can work on nearly every shot in a particular film (often numbering in the thousands), and when industry professionals frequently comment on the blurred boundaries between cinematography and visual effects. The infrastructural limitations of the studio system — the sets that could only be so large or so grand, the lot that occupied a limited expanse of real estate and could accommodate fictional streets that extended only a certain distance — were the brakes that forced even the most extravagant studio production to transition from an exercise in design into another conception of cinema more consistent with the theoretical and aesthetic tradition of photographic realism. What we see in the extravagant camera movements in contemporary cinema and in everyday corporate and government videos relies on our expectations about the realism of the long take and the continuity of space revealed by the mobile frame in a world defined by its inequality, discontinuity, and fragmentation.

Serge Daney once argued that the clash between cinema and television in the 1980s allowed filmmakers to explore an aesthetic that fell in between the filmic and the televisual. He maintained that films responded to the challenge of television by grafting the "'look' of advertising images from the 1980s . . . onto the old fiction machine of the 1950s," producing a hybrid form that "resembles a car on which one only highlights the clutch, the ability to start and restart, without knowing how to use the brakes. The machine is not enough: it needs a driver who knows how to stop it (by making it bump into something real) or who agrees to crash along with it."51 Like Walter Benjamin before him, Daney argued that modernity compelled us to grasp the emergency brake even as its paradigmatic forms of entertainment impressed audiences with the spectacle of movement. Perhaps the best way to view more contemporary products of design thinking is through the lens of studio-era cinema, from the perspective of the naïve spectator concerned that the helicopter is about to smash into the train station, the contemporary equivalent of the mythical Parisians who supposedly ran screaming from the theater during the first Lumière brothers exhibition and soon became an audience for Méliès, establishing this dialectical relationship between photographic realism and design that organized the cinematic imagination in the classical era. We should retain that capacity to be startled when the camera moves, sometimes imperceptibly, sometimes at an unsettling speed, across the threshold between them. In this era of cinematic architecture and computer-aided production design, that transition between imperfectly compatible media technologies and spectatorial imaginations is where world-making projects can crash into reality or where the camera itself can become a spectacle as it flies over and through a speculative world unfolding before our eyes.

James Tweedie is Professor of Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Washington. He is the author of The Age of New Waves: Art Cinema and the Staging of Globalization (Oxford University Press), which won the 2014 Katherine Singer Kovács book award from the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, and Moving Pictures, Still Lives: Film, New Media, and the Late Twentieth Century (Oxford, 2018). He is also co-editor (with Yomi Braester) of Cinema at the City's Edge: Film and Urban Networks in East Asia (Hong Kong University Press). He was named an Academy Scholar by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and he is currently writing a history of Hollywood art direction and production design.

References

- Howard McClay, "Pre-Production planning," Production Design 2, no. 1 (January 1952), 9.[⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Although drawing has always been a central theme in design education, the rise of digital technology has sparked a renewed interest in the subject. See, for example, A.T. Purcell and J. S. Gero, "Drawings and the design process," Design Research 19, no. 4 (October 1998); Michael Graves, "The Lost Art of Drawing," New York Times, September 1, 2012. [⤒]

- Robin Evans, "Translations from Drawing to Building," AA Files 12 (Summer 1986), 4. [⤒]

- Graves, "The Lost Art of Drawing." [⤒]

- This would be a variation on the observation made by Mario Carpo: "Now all that is digitally designed is, by definition and from the start, measured, hence geometrically defined and buildable." Mario Carpo, The Alphabet and the Algorithm (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011), 34. [⤒]

- Brian Jacobson, Studios Before the System: Architecture, Technology, and the Emergence of Cinematic Space (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), 2-3. [⤒]

- Ibid., 16, 25. [⤒]

- Beverly Heisner, Hollywood Art: Art Direction in the Days of the Great Studios (Jefferson: McFarland, 1990), 16. Because design became increasingly important with the expansion of the studios after their relocation to Hollywood and the development of the sound stage in the late 1920s, this essay focuses primarily on the studio era and after. It is worth noting that Eisenstein, the former set designer, also theorizes this link between cinema and architecture, with each imagined as an engagement with the modern condition of the mobile eye in space. See Sergei Eisenstein, "Montage and Architecture," trans. Michael Glenny, Assemblage 10 (December 1989): 110-131. See also Anthony Vidler's account of the architectural Eisenstein and the cinematic Corbusier in Warped Space: Art, Architecture, and Anxiety in Modern Culture (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001), 119-122. [⤒]

- Letter to Miss Gladys G. Howard of Chicago, Oct. 23, 1946, MGM Art Department Records, folder 44, Margaret Herrick Library, Beverly Hills, CA. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- See Brendan Gill, "Cedric Gibbons and Dolores Del Rio: The Art Director and the Star of Flying Down to Rio in Santa Monica," Architectural Digest: Academy Awards Collector's Edition (April 1992): 128-133, 254; Linda B. Hall, Dolores Del Rio: Beauty in Light and Shade (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2013), 156-7. [⤒]

- James Curtis, William Cameron Menzies: The Shape of Films to Come (New York: Pantheon, 2015), 12. See also Cinzia Giovine, Hans Dreier: An Architect Who Designed Movies (Master of Design), UMI (University of Cincinnati, 1998), 120. [⤒]

- See Charles Tashiro, "The Auteur Renaissance, 1968-1980," in Art Direction and Production Design, ed. Lucy Fisher (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2015), 102. [⤒]

- See Mario Carpo, The Second Digital Turn: Design Beyond Intelligence (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2017). [⤒]

- Greg Lynn, "Architectural Curvilinearity: The Folded, the Pliant and the Supple," Folding in Architecture, revised edition (Great Britain: Wiley-Academy, 2004), 28. [⤒]

- See, for example, Yasha J. Grobman and Ruth Ron, "Digital Form Finding: Generative use of simulation processes in the early stages of the design process," in Respecting Fragile Places: Proceedings of the 29th Conference on Education in Computer Aided Architectural Design in Europe (Ljubljana: eCAADe and UNI Ljubljana, 2011), 107-108. [⤒]

- On CGI crowds or the "digital multitude," see Kristen Whissel, Spectacular Digital Effects: CGI and Contemporary Cinema (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 59. [⤒]

- Paul Edwards, "Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, Time and Social Organization in the History of Sociotechnical Systems," Modernity and Technology 1 (2003): 191, 221. [⤒]

- See Jacobson, Studios Before the System; Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2015); and Nicole Starosielski, The Undersea Network (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015). [⤒]

- John Durham Peters, The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 10, 37. [⤒]

- Stephen Prince details the uses of Maya for "digital environment creation" in contemporary film productions. See Digital Visual Effects in Cinema: The Seduction of Reality (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2012), 166-8. [⤒]

- Carlos Calderon, Karl Nyman, and Nicholas Worley, "Architectural Cinematographer: An Initial Appraoch to Experiential Design in Virtual Worlds," in Computer Aided Architectural Design Futures 2005, eds. B. Martens and A. Brown (Netherlands: Springer, 2005), 135-144. [⤒]

- Ibid., 136. [⤒]

- Aron Temkin, "Seeing Architecture with a Filmmaker's Eyes," ACADIA 22: Connecting the Crossroads of Digital Discourse (2003): 227-233. [⤒]

- See "Aerial Cinematography and CGI for Architecture, Advertising, and Film," an AutoDesk University course by Gaspard Giroud posted in 2005; and "The Making of a Virtual Film for Architecture and Real Estate," an AutoDesk University course by Gaspard Giroud posted in 2016. [⤒]

- See Sean Ludwig, "Autodesk to buy hot video app Socialcam for $60M," Reuters, July 17, 2012.[⤒]

- Jeffrey M. O'Brien, "Autodesk's Cabinet of Wonders," CNN Money, Nov. 3, 2008. [⤒]

- See Herbert A. Simon, The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd Edition (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), xii, 2. [⤒]

- See Fredric Jameson, Signatures of the Visible (London: Routledge, 1992), 179-180. [⤒]

- The scene was shot with a combination of digital and practical effects, and when the scene transitions finally to a physical sound stage, the only way to maintain the pace of camera movement was to mount the apparatus on a camera car and hire stunt people to dive out of the way as it rushed past them. [⤒]

- See Charles R. Acland and Haidee Wasson, eds., Useful Cinema (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011). [⤒]

- Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (London: Verso, 2014), 13, 11. [⤒]

- Ibid., 92-3, 13. [⤒]

- Ibid., 26. [⤒]

- Ibid., 50. [⤒]

- Carpo, The Alphabet and the Algorithm, 34. [⤒]

- Kostas Terzidis, "Algorithmic Form," in Computational Design Thinking, eds. Achim Menges and Sean Ahlquist (United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 98. [⤒]

- See Greg Lynn, "Architectural Curvilinearity: The Folded, the Pliant and the Supple" and Lynn, Animate Form (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999). [⤒]

- Lynn, Animate Form, 11. [⤒]

- Ibid., 41. [⤒]

- John Chris Jones, Design Methods (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1992), 10., 10-11. [⤒]

- André Bazin, What Is Cinema?, trans. Hugh Gray, vol. 2 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 78. Bazin likens the temporality of cinema to the "present indicative tense." [⤒]

- Easterling, Extrastatecraft, 198-206. [⤒]

- Ibid., 56-8. [⤒]

- Daniel Morgan, "Max Ophuls and the Limits of Virtuosity: On the Aesthetics and Ethics of Camera Movement," Critical Inquiry 38 (Autumn 2011), 131. [⤒]

- Edwards, "Infrastructure and Modernity," 185. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- Serge Daney, La Maison cinéma et le monde, 2: Les Années Libé 1981-1985 (Paris: P.O.L, 2001-2), 174. [⤒]