Issue 6: Midcentury Design Cultures

Alfred Hitchcock had an odd affection for rear projection, matte paintings, and composite shots—in short, an affection for cinematic artifice.1 In his early version of The Man Who Knew Too Much (Gaumont-British, 1934), for instance, he depicted a downhill skiing accident by editing together separate images: an extreme long shot of a skier shooting down a slope; a young girl pursuing her loose dog onto the track; a close-up of a man's face; then another extreme long shot of the slope, the skier now collapsed and careening toward a crowd of onlookers; and finally the desired effect of the skier colliding into onlookers, which spares the young girl and her rescued dog. If this sequence looks unnatural today, it's due less to its montage construction than to the close-up of the man's face (figure 1). He is the skier, we are meant to believe; yet his close-up is obviously superimposed on a rear-projected image of a mountain. No spectator believes this image today, but in its moment it fit perfectly well with the sound-stage aesthetics developing in 1930's cinema.

But when Hitchcock remade The Man Who Knew Too Much (Paramount, 1956) more than twenty years later, such sound-stage artifice had become more jarring. The image of Doris Day and Jimmy Stewart in a carriage before rear-projected Marrakesh street life did not plausibly put them in Morocco but instead suggested to audiences Hitchcock's lack of commitment to location aesthetics and an overreliance on second-unit or stock footage (figure 2).2

What marks this historical passage is a techno-aesthetic development that André Bazin argues culminated in Italian Neorealism.3 Bazin claimed that camera developments allowing for deep-focus photography weaned the cinema from its interest in plasticity and led to a commitment to reality, in both its obduracy and its randomness. This commitment, Bazin thought, was best engaged by the openness of the photographic index — an openness, in particular, to environmental contingency, which made location shooting an aesthetic precondition and consigned studio-bound productions to a developmental stage in cinema history. Hitchcock was keenly aware of the emergent neorealist tradition. For one thing, he believed he had lost Ingrid Bergman to it.4 Indeed, just after shooting The Man Who Knew Too Much Hitchcock tried the neorealist idiom for himself in The Wrong Man (Warner Bros, 1956), using hallmarks such as location shooting and non-professional actors, but he would ultimately turn against it on principle. Aesthetically, he believed in a designed world, one minted in the mind and rendered concretely through the work of craft.5 In a peak phase of Hitchcock's Hollywood period, 1958-1960, his cinema came to oppose the openness of neorealism with design, and this philosophy emerged through his collaboration with graphic designer Saul Bass during those years, in particular on the movies Vertigo (Paramount, 1958), North by Northwest (MGM, 1959), and Psycho (Paramount, 1960). In what follows I argue against a commonplace assessment that the cinema left Hitchcock behind in its techno-industrial progress — making him old-fashioned come the '60s — by suggesting intentional resistance on his part, and even critique, rather than obliviousness to aesthetic currents. His project, as I understand it, was to raise artifacts of studio filmmaking such as rear-projection and matte paintings to a philosophical order. In this philosophical order, I argue, Hitchcock's commitment to the designed environment aligned him with the waxing of industrial design on the domestic scene and modernization theory on the international scene, in the sense that both were midcentury expressions of modernist confidence — scaling what I call "design-mindedness" from micro to macro — and both reached their internal limits within the liberal consensus.

Hitchcock Contra Neorealism

The schematic difference between Hitchcock and neorealism is analogous to the earlier historical opposition that Gilles Deleuze worked out between Hitchcock and Jean Renoir. Deleuze says that the unit of the shot has "two aspects": it "presents modifications of relative positions in a set," with the "set" referring to whatever is provisionally captured or staged within the frame, and "it expresses absolute changes in a whole" — Deleuze also calls it "the Open" — which is the set of all possible sets.6 One aspect or another receives emphasis, either the provisional frame and the positions within it, or the changes made absolute because the whole registers in them. The Hitchcock shot exemplifies the former aspect, as it "confines all the components," and the Renoir shot the latter because its "space and action always go beyond the limits of the frame." Both entertain a relationship with what Deleuze calls the "out-of-field," but the Hitchcock shot isolates a system whereas the Renoir shot extends every set into a larger set with which it communicates. These modes of framing sit within a classical regime, though each strains it in a different way. The Hitchcock shot produces a "mental image," as Deleuze puts it, which is to say its parts have been cognized in a set of formal relationships. He cites Eric Rohmer and Claude Chabrol's remark that in Dial M for Murder (Warner Bros, 1954) the "whole aim of the film is only an exposition of a reasoning."7 To the extent that action matters in Hitchcock — and it does not in itself, as indifference toward its trigger (MacGuffin) attests — it does so because it allows us to map a field of relations. Hence the peculiar scene in Psycho in which the psychiatrist seems rapt as he explains the murderer Norman's mind, as though he were addressing his colleagues rather than the grieving relatives of the victim; the actions matter less, for Hitchcock, than their analysis. Contrast this with the Renoir shot, and in particular what flows from it — neorealism — wherein action is unmoored altogether. In it there is a breakdown in what Deleuze calls the "sensory-motor schema," such that a perceiving center (a subject) no longer bears a natural relation to the actions it might carry out. It is just wandering adrift.8

The upshot of this dual challenge to the classical regime is a bifurcated modernism. Internal to the modernization process — namely within institutions such as the corporation, university, and government that begin promoting modernism — there emerges a confident design-mindedness comfortable with abstraction, which I will here call "cold-war modernism."9 Externalized by the same process, however, are modernist forms of beset humanism, iterated out as existentialism, absurdism, decadence, and so on.10 Hitchcock's cinema is fed by the latter, to be sure, but his fascination with the designed environment drew him increasingly toward the former over the 1950s. Most overtly, he signals his interest in design by thematizing it, casting Barbara Bel Geddes (daughter of famed industrial designer, Norman Bel Geddes) in Vertigo as Midge, a designer herself, and by having the character of Eve Kendall tell Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest that she is an industrial designer. But more fundamentally, it was in collaboration with Saul Bass that Hitchcock would apply design ideas to his movies at the level of formal construction. Deleuze had approvingly cited François Regnault's observation that in certain Hitchcock movies there is a "principle geometric or dynamic form" holding together the "global" and "local" elements, and that this pattern "can appear in a pure state in the credits." Fredric Jameson would later observe something similar, noting, for instance, how the grid of parallel lines in North by Northwest unites its otherwise disparate forms: its skyscrapers, cornfields, and the cliff faces of Mount Rushmore. Slavoj Žižek recognizes, too, that the coherence of Hitchcock's cinema lies in its design elements.11

While Deleuze, Regnault, Jameson, and Žižek all acknowledge that a governing shape has been imposed on select Hitchcock movies — notably Vertigo, North by Northwest, and Psycho — none of them observe that these are precisely the movies on which Hitchcock and Bass collaborated. This oversight is owed to the auteurist bent of film criticism.12 Deleuze, for instance, when commending Regnault's analysis, says it "is the necessary research program for all director-analysis."13 Part of what gets lost in such analysis is a hope of understanding film form in relation to industrial configuration, and restoring the part of Saul Bass — as an ambassador of the design world — is a way to correct this.14 It will let us analyze Hitchcock movies in relation to their industrial situation, and it will reveal that as the studio system was disarticulated and Hitchcock himself was displaced within it, migrating from Paramount to Universal, his movies gained in aesthetic coherence thanks to design philosophy. Design is the figure of the postindustrial moment, I argue, precisely because it aimed to extract meaningful patterns from industrial ruin. In what became a bible of postwar design, Language of Vision, György Kepes claimed that within the "tragic formlessness" of this era, within its "whirling confusion," design had the charge to "build unified entities, those forms of experience called visual images."15 Kepes deemed cinema an apt medium for such visual images, and it was his one-time student, Saul Bass, who would port this philosophy into that form by way of his collaboration with Hitchcock.16 My purpose is to read the image ensuing from their collaboration — the mental image, the design image — for the orientation it gives on the topos of its production, offering, as it does, something of a counternarrative to the emergence of New Hollywood, conventionally understood.

To try out this interpretive practice, we might begin with an image from Marnie (Universal, 1964), a movie which did not involve Bass but was a swan song for certain key Hitchcock collaborators, including cinematographer Robert Burks, editor George Tomasini, and composer Bernard Herrmann. The image is of Marnie's return to her childhood home in Baltimore. The end of her street opens onto a foreshortened image of an ocean liner docked in the harbor (figure 3). It is obviously a painted backdrop, not simply in the way that paintings always appear as such for their lack of volumetric space but because it is photographed from two perspectives. In one, the painting creates the typical, if unconvincing, effect of sound-stage photography, but in the other, it creates a strange, almost oneiric distortion in the planes of the image, all of which seem to be collapsing into each other (figure 4).

Production designer Robert Boyle had only intended the forced perspective of the painting to be seen in the high-angle establishing shot, but Hitchcock insisted on shooting it again from street level. He "didn't care if it didn't look realistic," Hilton Green reported, and he rejected "alternative suggestions from his collaborators." It "wasn't for lack of money," Jay Presson Allen added, "because Universal would have given every cent."17 Hitchcock did not override his crew's objections so much as he insisted on displaying their craft. What Hitchcock got from such display is what François Truffaut called his "antirealistic effect," which plays in this moment as a sly rebuke to neorealism.18 Truffaut understood Hitchcock's work to be incompatible with the turn to realism, suggesting to Hitchcock that The Wrong Man had failed owing to the "total conflict" between his style and the documentary aesthetics the material required. Though Truffaut felt "it should have been handled like a newsreel reportage," Hitchcock worried it would then be "rather dull." He had once used these grounds for dismissing The Bicycle Thieves (De Sica, ENIC, 1952), telling the press he had watched it with his housekeeper and she was "half bored by the masterpiece." While Hitchcock took audience response to be an important datum, he didn't in truth consider his housekeeper's boredom to be the final word. He thought The Bicycle Thieves was brilliant, featuring a "perfect double chase — physical and psychological."19 In other words, he respected its formal design, not the unaffected style that it put in vogue.

Here, though, we might pivot back to Marnie, because in its antirealistic effect Hitchcock pursued formal achievements similar to The Bicycle Thieves — Marnie's is a double return, "physical and psychological" — but in a style radically at odds with neorealism. He discloses the constructedness of its form where neorealism would conceal it. Marnie's return to Baltimore reveals that childhood is still too much with her, that she is walled in by it and unable to cast its relationships in the perspective that adulthood should grant her. Shooting the painted backdrop in a forced perspective, though, makes the too-closeness of Marnie's family origins formally correspond with studio space. It roots the movie, that is, in its topos of production, even as that topos — the studio — is being rearranged and superseded. Hitchcock's "Paramount Team" worked together for the last time on Marnie, as Tomasini died the year the movie was released, and Burks died in a tragic accident several years later (and he and Hitchcock did not work together in the interim).20 So devoutly was Hitchcock trying to reconstruct the talent he had assembled at Paramount on the Universal lot that he conceived Marnie as the role for Grace Kelly's Hollywood comeback. Kelly withdrew from the production when some incidental politics caused the Prince of Monaco to forbid her the part, making Marnie, almost by default, a movie about the lapse of Golden Age stardom and the enlistment of art design to compensate for the charisma thereby lost. Hitchcock trusted Tippi Hedren's acting very little, but in his move to Universal he was joining two art directors that he very much trusted — Robert Boyle and Henry Bumstead. Boyle had designed Hitchcock's previous movie, The Birds (Universal, 1963), around Hedren, stitching her into what Boyle has called "amazingly complex piece[s] of film," built up in composite as they were from so many separate elements.21 This backstory to the movie is pulled to the surface in the painting of the Baltimore docks, the expressiveness of which does more to explain Marnie's condition than does Hedren's performance.

From Bauhaus to the Bates House

Noting that Marnie's state of mind has been exteriorized (a matter of art design) rather than interiorized (a matter of acting) puts Hitchcock in the lineage of German Expressionism, as scholars have commonly done. But I posit that his cinema is equally illuminated when placed in the lineage of the Bauhaus, the German art school which moved from Weimar to Dessau to Berlin and, eventually, Chicago.22 There its influence fanned into the culture of the American Cold War, profoundly shaping the applied arts in general. Saul Bass is a nexus in Hitchcock's cinema because, having studied with György Kepes at Brooklyn College and adapted his design philosophy from Kepes and László Moholy-Nagy, he helped formalize certain Bauhaus ideas that had perhaps always been latent in Hitchcock's work.23 What Bass made coherent for Hitchcock was the reason for matching the credit sequence to the mise-en-scène throughout the body of the movie. Edward McKnight Kauffer, it's worth noting, did this for Hitchcock as early as The Lodger (Woolf & Freedman, 1927), coordinating intertitle graphics with the diegesis; but the practice became definitive for the Hitchcock-Bass collaboration. For Bass had developed in his graphic design work a style based on clean, simplified lines in directional relationship, and thus he brought to these Hitchcock's movies — starting in the credit sequence — a sense of one dynamic shape that pulled the spectator's eye ineluctably along a vector. He drew forth a geometry of audience desire from relations in the object world, which served as a graphic correlate for Hitchcock's interest in audience response. What inspired Bass's style was Moholy-Nagy's notion of the "macrophotograph," modeled in his book The New Vision by aerial photographs that revealed, as Jan-Christopher Horak puts it, "the large-scale relationships of geographic formations." Sensitized to different properties in these formations, such as "light, density, color, and form," one can discern a shape in their structure.24 The idea that large-scale relationships, if indexed to given properties, might be granted a governing shape was the heart of Bass's design philosophy.

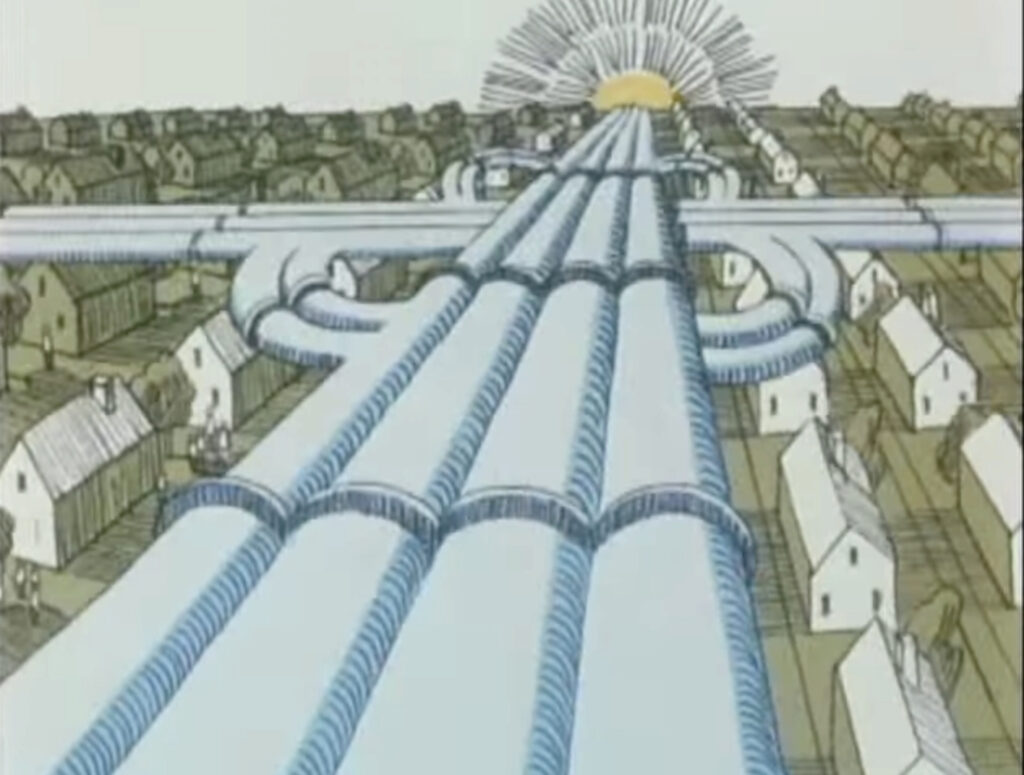

The movies Hitchcock and Bass worked on hence each assumed one dominant shape: in Vertigo it was the spiral, in North by Northwest the grid, and in Psycho the interrupted line. We might pursue such analysis with respect to North by Northwest, because it thematizes a relation between this kind of modular thinking (one design made portable and scalable) and the Cold War, and it will ultimately be my interest to spell out the Cold War implications of this kind of design-mindedness.25 The movie is patterned by the grid — the quintessential modernist shape — and this pattern is first declared in the credit sequence, designed by Saul Bass.26 Here the grid begins in a purely graphic state, blue lines criss-crossing a lime green background, but the form then becomes a glass-and-steel skyscraper on which the credits line up (figures 5 and 6). It's a cheeky gesture, given how important a negotiation the point-size of an actor's name in the credits had become throughout the 1950's: the grid lets viewers measure very precisely the scale of each actor's name. Cary Grant is bigger than MGM, but Alfred Hitchcock is bigger than them all (figures 7, 8, and 9). A paradox of the modernist fascination with the grid, as Rosalind Krauss has argued, is that there is seemingly no "less fertile ground" for "exploration" and yet careers were dedicated to exploring it.27 We might expect it to yield the skyscraper, as it did for the Bauhaus architects, but what else is naturally offered up by its regularized scheme? Thus when Roger Thornhill (Cary Grant) arrives in Indiana to meet Mr. Kaplan in the cornfields, we are surprised to see that the grid has in fact been imposed on the organic forms of nature (figure 10). Agricultural production, that is, happens on the schedule of ratiocination very much the same as skyscrapers do. The grid, which is "antinatural" in Krauss's account, has rendered nature in its image.

Figure 5: Grid in its purely graphic state.

Figure 6: From the grid emerges a Manhattan skyscraper, its parallel lines underscoring the screen credits.

Figure 7: The MGM credit.

Figure 8: Cary Grant gets larger point-size.

Figure 9: Hitchcock's still larger point-size

Figure 10: The grid has been imposed on the rural landscape as well as the urban.

This fact of form rises to the thematic level in the movie's Cold War machinations, which involve intelligence agencies and spies and state secrets. Thornhill arranged to meet Mr. Kaplan because the two men's identities had been confused (spies were hunting Thornhill on the premise that he was Kaplan) but scenes in CIA offices reveal that "Mr. Kaplan" does not exist. He had been invented by the CIA to throw off the scent of their real agent, Eve Kendall, and Roger Thornhill simply "stumbled" into the role. The movie plays this as a self-reflexive joke on acting and performance, but its larger point is that the same skill-set that distinguishes Cary Grant is employed in statecraft. The CIA is but an interchangeable agency ("FBI, CIA, ONI, we're all part of the same alphabet soup") charged with administering a population. The invention of "Mr. Kaplan" only dramatizes the empty-slot citizenship that is the main technology of the administrative state. That Thornhill will not escape the grid, whether in New York City or Indiana, is stated forthrightly — and with chilling indifference — by a CIA functionary: "Goodbye, Mr. Thornhill, wherever you are." In the endless substitutability implied by such population management, however, North by Northwest is asserting Hollywood's role. A star is not a number but a face. The familiarity of Cary Grant's face is subject to a series of jokes, bent on confusing whether he is an everyman (the "O" in his initials, ROT, stands for nothing) and can assume the form of Mr. Kaplan by dint of his anonymity, or whether he is a star who is familiar by virtue of his exceptionality. "It's a nice face," Eve Kendall tells him repeatedly, and when she tells him her room number, 3901, he responds, "It's a nice number." Faceless but numbered, or the singularity of a nice face. Hence the final use of the grid is the great synthesis: as Roger Thornhill and Eve Kendall are stranded on the sheer walls of Mount Rushmore, we notice that its striations make a grid of the mountain. Like the cornfields, the mountain is made productive (qua art medium) by the imposed form of the grid, but here what emerges from the empty slots of its form are the singular faces of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, and Lincoln (figures 11 and 12). What redeems the empty-slot formalism of the grid — as a technique of population management — is its capacity to produce stars. Cary Grant, Hitchcock asserts, can emerge from the production design, establishing a figure-ground relation that is a national desideratum, whereas Tippi Hedren will come to mark star production shortfall in her turn and recede into postindustrial design work.28

If Cary Grant's state function is analogous to that of the Rushmore presidents, his domestic function within North by Northwest is as a "Madison Avenue man," as Vandamm calls him, which is to say he is the figure of advertising and consumer culture. Grant's split character of Thornhill/Kaplan evokes what David Crowley and Jane Pavitt call "the twin props of Cold War modernity: consumerism and militarism."29 In Grant's identity confusion, the movie suggests the imbrication of domestic consumerism and the national-security state. Though advertising doesn't seem to feature too prominently in the movie, despite it being Thornhill's occupation, one way to understand its disproportionate significance in the movie is as the specter of degraded art. In the famous auction scene, Thornhill begins to bid on lot 109, a painting the auctioneer calls a "superb example" of an "early 17th-century master," but Thornhill underbids because he doubts its going price. "Twenty-two fifty for that chromo," he sneers. The next piece of art Thornhill likewise calls "a fake." There is an explanation within the plot for his disdain of art's value — he is creating a scene in order to get arrested — but because the advertising industry had come to instrumentalize art so routinely, we can understand his profession within the movie's broader condemnation: he is an agent of art's devaluation. In Cold War modernism, what degrades art is precisely that its value is generated by a force extrinsic to itself rather than by its own intrinsic logic; the modernist paradox, as we see in Serge Guilbaut's critique, is that even art premised on its own inutility, turned inward for the sake of clarifying its medial properties, such as abstract-expressionism, can be made into an advertisement for the political system permitting it. Here, too, we can invoke Reinhold Martin's take on what a close cousin Kepes's "new vision" was to "the emergent pattern of institutional and technological networks that later became known as the military industrial complex."30 Put bluntly, such a problem is built into the figure of the designer, hence when North by Northwest pairs off Eve Kendall and Roger Thornhill, it presents her as an industrial designer (but not really) and him as a Madison Avenue man (but not only) because the work of such professions redounds to the national-security state as a matter of fact: the movie knows this even if these professionals do not. North by Northwest might be read, then, as a reckoning with art's geopolitical implications, and it emphasizes those arts most openly implicated. Sculpture and architecture, say, but not painting. Thornhill references each of the former in confronting Vandamm. "I'll bet you paid plenty for this little piece of sculpture," he says of Eve Kendall, but we can also peg this as a reference to the sculptures of Mount Rushmore. Thornhill then asks Vandamm how he plans to kill him: "Am I to be dropped into a vat of molten steel and become part of a new skyscraper?" We can peg this as a reference to Wallace Harrison and Max Abramovitz's C.I.T. Building, which Saul Bass used in the beginning of the movie to score the film's credits.

Paintings are in fact emphasized in North by Northwest, just in another register. As in Marnie, paintings are matted into North by Northwest as backdrops. The twist is they are paintings of architecture. Hitchcock's favored production designers, Robert Boyle and Henry Bumstead, both studied architecture at USC before joining the art department at Paramount. In film, they became architects in miniature, constructing scaled versions of "Zanzibar, Singapore," and so on.31 I want to suggest that Hitchcock's interest in painting, which has received critical attention, is really an interest in film as a kind of architecture, as a version of the painting, that is, made dynamic and habitable.32 Erwin Panofsky said that film "is the nearest modern equivalent of a medieval cathedral," and that "film actors and film directors" are "comparable" to "plastic artists and architects," because film is a temporal process that takes a "permanent" shape. It is time spatialized, as architecture is said to be music frozen.33 North by Northwest's paintings of buildings, therefore, are hyperliteralized images. On one hand they enact the proposition that film is a painting set in motion — by way of a literal painting with a figure actually moving within it (figure 13) — while on the other they demonstrate that film's movement and its elapse of time are permanent, like architecture, by way of a painting of architecture. In the case of the matte painting of the United Nations Secretariat Building, there is, too, an eerie beauty that is at once specific to film and anti-realistic. The image I wish to examine in more detail, though, is the matte painting of Vandamm's South Dakota home (figure 14). The house is clearly a reference to Frank Lloyd Wright's architecture, with its Prairie Style recalling the horizontality of such famous designs as the Robie House and its cantilevered terrace recalling Wright's most famous home, Fallingwater. Robert Boyle mocked up this faux Wright house (figure 15). In its painted form, executed by Matthew Yuricich, it blends into plausible perspective with the unpaved road that Thornhill walks along, even if the illuminated windows of the home are obviously flat (i.e. painted) and visibly imposed behind the dynamic elements of the film. In playing static and dynamic elements off each other, this frame models what Tom Gunning has said intrigued Hitchcock about paintings, namely the "crisis" posed by the desire "suspended" in the painted image and its "malevolent" relation to the dynamized elements within the frame.34 This fraught relation suggests that the modern home is not a site of stasis, which is not to say that it is unhomely, per se, as the gothic house is. Rather, that homeliness is no longer fixed in place; it has now been mobilized and set free from any physical moorings. This impression is only reinforced by the location of Vandamm's aerie. It is, after all, perched atop Mount Rushmore and outfitted with a landing strip, so that he can fly away at a moment's notice, making it less a traditional home than a node of transit.

We can derive the meaning of the Vandamm house by juxtaposing it with the famous Bates house from Hitchcock's next movie, Psycho. If the Vandamm house models a new mobility, the problem with the Bates house is its fixedness. The highway system has left it behind in the Victorian past of the house's architecture, a past in which the home would have connoted rootedness. John David Rhodes has argued that the movie stages the condition of uprootedness in terms of property relations, by opposing owners (Norman Bates) and renters (Marion Crane).35 In this regard the transient renter is coded as modern by way of the architectural morphology: whereas the Bates house is vertical (but not in the modern way a skyscraper is), the Bates Motel is horizontal, much like Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie Style. Hitchcock noted the importance of their contrasting shapes. "I chose that house because I realized that if I had taken an ordinary low bungalow the effect wouldn't have been the same," he told Truffaut. "Our composition," he explains, was "a vertical block and a horizontal block."36 Such a contrast had also been struck in the United Nations headquarters, which was the one location shot they were intent on getting in North by Northwest (as opposed to the high-angle shot down the glass wall of the Secretariat Building, which they were fine replacing with a matte painted rendition). The United Nations headquarters is indeed two buildings in counterpoint, the high-rise Secretariat Building and the low-slung General Assembly Building, i.e. "a vertical block and a horizontal block" (figure 16).37 It places two modes of modernism in counterpoint, whereas Psycho not only sets the two shapes against each other as architectural signatures of distinct historical periods — a Victorian then and a Modern now — but also reduces its buildings to the status of abstract shapes. In accord with the design schema of the movie — the interrupted line — the opposed shapes of the motel and house recall the broken lines of the credit sequence, racing horizontally and then vertically (figure 17 and 18).

The ordering power of Psycho's fundamental shape, then, pertains to history qua linear process, and this ramifies on all levels: family history, national history, and formal history. A line between Norman and his mother has been interrupted, as has the one between Sam and his ex-wife, and Marion is seeking to interrupt the one between the oil man and his daughter; a transportation line between small towns, wherein the Bates Motel was a convenient node, has been interrupted by Eisenhower's National System of Interstate and Defense Highways; and a causal line between film shots, known as continuity editing, has been interrupted by the fragmented storyboard that Saul Bass drafted for the infamous shower scene. What I wish to stress, though, is that the shape has been figured in the architecture — in architectural history, more precisely — because Hitchcock and his crew had to decide for Psycho, as they did for North by Northwest, whether to represent the edifices of the house and the motel in matte paintings or in physical structures. This time, they chose to build physical structures on the backlot of Universal Studios. Eschewing the matte painting was no slight to Hitchcock's crew, whose work he would display in two dimensions again in Marnie, but it was rather a commitment to the three-dimensional space of Universal Studios.

Though Psycho was technically a Paramount movie (the last one, in fact, Hitchcock contractually owed the studio), it was in substance a Universal movie.38 He made it on the Universal lot because it was the studio Lew Wasserman was colonizing in his bid to reset Hollywood's production regime.39 This was a complicated process, traceable in a series of transactions carried out by Wasserman between 1959 and 1962, but it involved the revaluation of the studio as a production site amidst the trend toward runaway production otherwise reshaping the industry in those years. To reclaim studio land, Wasserman made tactical use of routinized television production, by way of Revue Productions, a unit of MCA that he had installed on the Universal lots before acquiring the studio. As Hitchcock's agent, he helped begin the Alfred Hitchcock Presents series that would publicize Hitchcock as a persona and reattach him to the studio enterprise in the moment it was seemingly being undone. But Wasserman's reengineered studio would not form an unbroken line with the studio system of old, inasmuch as free agency now ruled labor relations, thanks in large part to Wasserman's MCA. The studio would never again be a landed operation, not in the stable way it was before the divorcement decree, but the story Psycho tells about property in its traditional form being left behind by modernizing logistics is a reverse image of property as it was financially transformed by Wasserman's Universal. Building the Bates house on the Universal lot was not only a means to symbolically associate the movie with the studio's stock-in-trade genre of the 1930s — the horror movie — but it was also an early step toward mobilizing the studio as a tourist attraction. Wasserman would initiate the Universal Studio Tour in 1964, spectacularizing the labor localized on this lot while bringing it under the sign of a leisure economy. The Bates house, a holdover from the traditional past within the diegesis of Psycho, made henceforth a prominent icon of the studio-as-theme-park, remains outside the movie a harbinger of the so-called new economy.40

The Modular Mind

In his essay on spatial systems in North by Northwest, Fredric Jameson delimits space in the movie in terms of openness and closure. There are seemingly open spaces, such as the cornfields in the crop duster sequence, which are nonetheless privately owned by agribusiness and hence closed to us despite appearances. But in contrast there are the great estates on Long Island with a diplomatic function, such as the Townsend estate, and despite being private homes they have an open character to them. Because such space is for wining and dining ambassadors, it might be deemed semi-public. What Jameson ultimately fastens on, though, is how North by Northwest cites the final scenes of Saboteur (Hitchcock, Universal, 1942) but swaps out the Statue of Liberty for Mount Rushmore. Production designer Robert Boyle made both set monuments, which indicates that the citation is self-conscious, yet the climactic action of Saboteur begins within the Statue of Liberty while it happens on the surface of Rushmore in North by Northwest: the large-scale head of the Statue of Liberty is open — it has an interior, that is — whereas the similar heads of Rushmore are closed, insofar as they are solid rock through and through. I note this in such detail because it lets us see how the act of figuring space is, in Psycho, explicitly a matter of understanding cognition in spatial terms. The Bates house is the open form of Norman's mind. You can literally walk into it and see the skeleton in his closet (or fruit cellar) in such a way that Freudian psychoanalysis has seemed to cede its immaterial talking cure to the more material procedures of art design. Slavoj Žižek, for one, sees in the Bates house a physicalized architecture of the psyche: the upper floor where Norman's scolding mother presides is the superego, the ground floor where he greets guests is the ego, and the basement where he hides his mother is the id.41 That Norman can move his mother from the upper floor to the basement, and thus dynamize her function in his psychic life, delineates a mental process for us in spatial terms. This is not new, as an archaeological model has long been used to metaphorize the unconscious mind, but the attempt to coarticulate the mind and the built environment in a dynamic operation is the calling card of midcentury design.42

In what follows, I want to track this representational technique in the films Saul Bass made after his Hitchcock collaboration, chiefly Why Man Creates (Pyramid, 1968) and The Solar Film (Wildwood, 1979), in part to illuminate the influence Bass's design ideas had on Hitchcock's cinema and in part to demonstrate what I have called design-mindedness. Bass's Why Man Creates mimics Psycho, insofar as it imputes a shape to the mind, but the mind given shape in Psycho is individual whereas in Why Man Creates it is historical. Human rationality, in Why Man Creates, is shaped as an edifice, and the movie begins as a long tracking shot from the foundation of this edifice to its ceiling, the nuclear age (figure 19). The edifice is cartoon-animated and meant to be comical but it nonetheless evinces the teleological assumptions of midcentury design, namely that the good life is an end we progressively build toward by way of scientific advances, at first theoretical and then applied.43 The edifice as a whole figures the rational faculty as a historical achievement. It sets up the question "why man creates," but embeds in it a methodological elaboration of how man creates. On the ground floor of history, the movie places a hunter-gatherer solution to catching prey within a physical enclosure whose structural integrity owes to the form of the arch (figure 20).

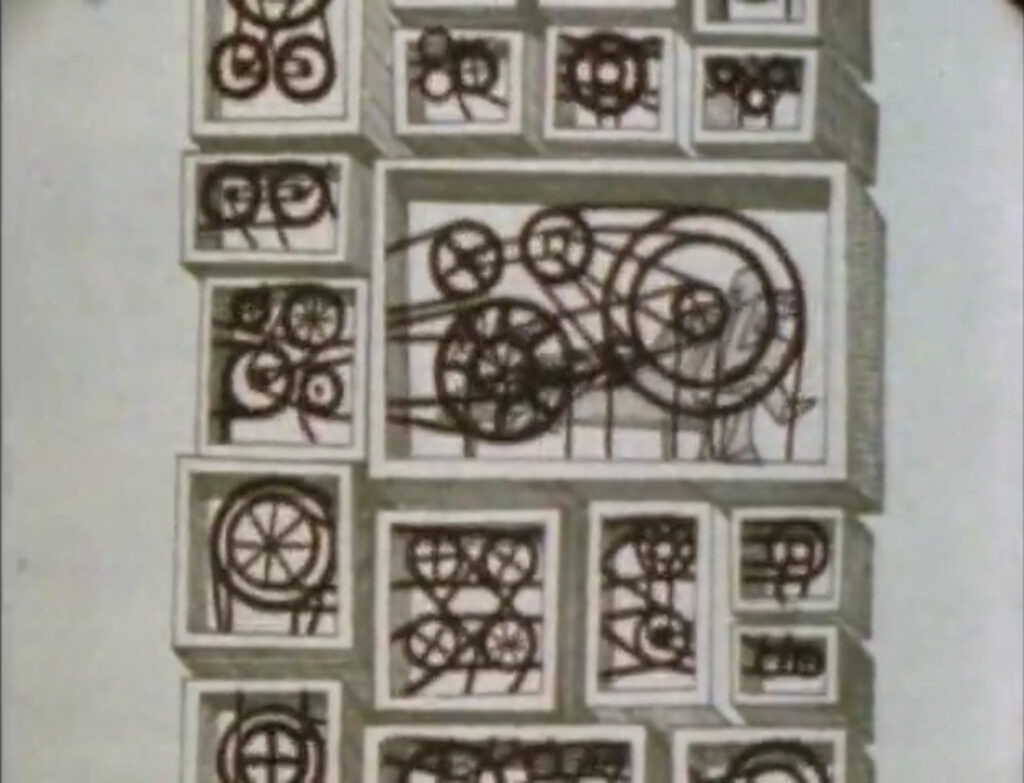

It literally sets the solution in stone, which recalls for us the cave paintings at Lascaux, but more important — for my analysis — is the architectural feature of the arch.44 This form, presumably derived by Paleolithic people from cave openings, connects the hunter-gatherers to the Romans, for whom it was the basis of aqueducts, bridges, and vaulted ceilings (figure 21). Though discontinuous (Egyptian floors of the edifice, wherein the pyramid is the prevailing shape, intervene between the early hunter-gatherers and the later Romans) the form of the arch can be ported through history; it is, in Saul Bass's depiction, a transhistorical form. So, too, are the lever and the wheel. The levers and wheels from the bottom floors of the edifice will be reimagined in the industrial era as parts in complex machines, and this, finally, is Bass's observation on how creativity works: It is carried out unit by unit, researcher by researcher, and artist by artist, and hence the methodology of creative activity is not only the unit as such, but the shape of the unit and the combinatory possibilities that such a shape affords (figure 22).

Figure 21: The arch moves discontinuously through history, from early hunter-gatherers to Roman civilization.

Figure 22: The levers and wheels discovered by Paleolithic ancestors are reconfigured in the endless machinery of the industrial age.

What Bass is modeling here is design-mindedness, a sensibility which was derived from modernism and woven into a panoply of professions in the postwar years — design and architecture, to be sure, but also business management and politics (as I will explain in the concluding section). Bass and his contemporary Paul Rand were two prominent avatars of this sensibility. In Rand's Thoughts on Design, he charges this sensibility to "visual communication." An idea can be gotten across, he writes, when captured "as an organic and functional unit, each element of which is integrally related to the others, in harmony with the whole."45 For Rand and Bass alike, the "unit" lets them delimit a set of problems, just as the frame does for Hitchcock. This is the aesthetic of the closed system. But as Deleuze will say of the set in relation to larger sets, "A closed system is never absolutely closed" but is "connected in space to other systems by a more or less 'fine' thread."46 Both Rand and Bass believed that tracing this fine thread made design a transhistorical project, hence we see the continuity of the aesthetic project beginning for each of them in the Lascaux cave paintings but culminating in the midcentury imposition of a scientific framework on the design concept. Bass would use such language in discussing his perspective on his craft. "All phenomena are connected," he said, "and all phenomena reinforce each other, so if we observe the set of phenomena and explain them... [it would be] a matter of time before the underlying scheme, and the underlying connection, and the underlying rationality of all phenomena will be revealed."47 Subtended by scientific method, what otherwise seems the intuitive feel of good design is rendered an aesthetic-historical project. Its outcome, Bass claimed, would be a "beautifully machined, rational thing that works beautifully."48 It must, so the designer believed, be beautiful.

That the aesthetic mandate of design-mindedness should inform the machining of human history makes sense of Bass's The Solar Film, a valedictory expression of the liberal consensus.49 Commissioned by Robert Redford's Wildwood Productions, the movie resembles Why Man Creates in significant ways. First, it means to encapsulate history — in this case, natural history — in less than ten minutes of screen time. "The sun rose upon a young, barren Earth," it begins, and after "life beg[ins] its evolutionary journey," the movie ends by sounding geopolitical notes: "You don't have to worry about those foreign oil producers," says someone in a voiceover medley, while another person welcomes solar energy because "you worry less about terrorists and other people who use violence to achieve their aims." The final image is the sun again rising upon the Earth, but here a human time-scale nests within the longer scales of natural history, the suggestion being that human problem-solving, which first threw these scales out of whack, would in the end harmonize them once more. Its confident design-mindedness, in short, is marked by reductionism and harmony. It's worth noting that its utopian mission — to promote a belief that problems might be reduced to manageable scale and expert knowledge brought to bear on them — was in its moment a holdover of the liberal consensus that was brought to rout in the ascendancy of the Reagan revolution. And second, The Solar Film resembles Why Man Creates insofar as both are segmented: they both intermix cartoon animation and live-action film, and in their structures the main building blocks they deploy are montage cells. Jan-Christopher Horak remarks these traits, calling these movies "highly episodic meditations" and noting their constitution from "montage of mostly short shots."50 What should be added is that at either scale (the episode or the montage shot) the notion of uniform shape obtains, which implies that structure taking hold at the macro level is only a matter of the micro-level unit being scaled up.

In scaling from montage cell to episodic segment, Bass takes us from the aesthetic to the geopolitical. In the third segment of The Solar Film, cartoon imagery is transformed into a filmed image of the surf, and the glistening sand and lapping water reflects for us the sun, otherwise out of frame. The image rhymes with the opening and closing frames of the sun rising on the Earth's horizon, as well as with the sun's capacity to centralize human activity within the animated segment (figures 23, 24, 25, and 26). The image of the surf lap-dissolves into an image of a young boy, his chin cupped in hand, an image of absorption in nature. In voiceover the boy says, "The sun feels good on your skin, you know, when you're wet and cold, and it dries you and warms you up." At the micro level, then, we get the phenomenological experience of the sun as pleasure, but one incipiently shot through with cognition: "feels," that is, followed closely by "you know." The montage cells, here, are the sun-warmed, lapping surf combined through a dissolve with the boy mentally absorbed in the fundamental pleasure of sensation. But from montage cell to episodic segment — as the boy is followed by a mother and daughter, then by a peach farmer, then by an adobe architect, and finally by a scientist describing "solar collectors" and "photovoltaic cells" — the impulse that at first is aesthetic gets converted into one that is geopolitical. The direct experience of sun on the skin is contrasted with the indirect historical experience of it. "Primitive man" had been frightened by the eclipse, we are shown, and his "fear had turned into worship." Ritual helped regulate the fear that the sun would disappear. Yet "meanwhile underground lay a vast store of the sun's energy, trapped, waiting," until one day a person discovers coal, and the next day someone else discovers oil, and from there fixtures of industry such as derricks, pipelines, and smokestacks spread over the surface of the Earth. The endless spread of prosperity in this form meets its terminus when airplanes seem to burst from the sun and an anchorman reports that "the value of the dollar dropped again today on world money markets with news of the latest OPEC price increases." The movie places the harvesting of solar energy in opposition to the extractive industries of coal and oil; it scales up the original aesthetic experience of the sun — which is both direct and immediate — into a large-scale industrial relationship, one whose geopolitical effects will be benign, "essentially utopian," in Horak's words.51

The point of all this is that from small- to large-scale, from aesthetic to geopolitical, Bass has imprinted a single, governing shape in his material, namely the shape of the sun on the horizon. Horak notes how ubiquitous this elemental shape is in Bass's design repertoire. "A signature Bass image," Horak says, it appears on one-sheets such as The Big Country (Wyler, 1958), in a corporate identity campaign for Lightcraft, and variously in television commercials.52 The meanings wrung from an iconic image such as the sun are of course nearly infinite, but Bass's Bauhausian orientation on it suggests that the dynamism of the sun's processes is what makes it a narratively and thematically coherent shape in his filmmaking. In The Solar Film the image holds fascination in one register — that of architecture, or urban planning — insofar as our relationship to the sun organizes our cities. In an early scene, for instance, a dwelling is shown that gets sunlight in winter months but shade in summer months. When oil fields are discovered, in the animated segment, industrial towns are shown spreading across the landscape. The final images in the movie, in sequence, are the final sun on the horizon, with a diapered toddler walking toward it, but preceding this is the image of solar banks on an energy farm (figure 27).

This is a figure of economy, as would be any image of energy stores, yet it seems organized nonetheless on the template of the sun: a circle radiating outward. What is graphically irreducible in this image, what makes it a mental image is that the very process of reasoning — of the aesthetic image in service of cognition — is at one with a large-scale image of economic organization. Here we might refer this back to Psycho, wherein the image of Norman's mind is his Victorian house, and the placement of this house has been superseded by the large-scale reorganization of logistics in the postwar economy. Norman's mind, his process of reasoning, is thus marked as too traditional, too much in fee to the family and social patterns handed down to him. Bass offers, by contrast, a more progressive image of the mind in relation to social organization, one whose fundamental shapes are derived from nature, thus scalable and portable according to properties discovered therein. Bass offers an image of the mind not rooted in tradition, but mobilized, rather, by the disposition of natural resources. It is an image of the modular mind, and the virtue of this image in a postindustrial economy is that it can be transplanted anywhere; it can be resized according to situation. No need for fixed production — so Hollywood learned — only runaway production, with hubs assembled the world over and connected by the Deleuzian "fine thread" placing sets in communication.

Twilight of the Liberal Consensus

In closing I want to line up this late period of Hitchcock's cinema with the liberal consensus because — in short — they decline in tandem. The reasons for this only loosely correlate, but correlating them is nonetheless worth it because it reveals the lifespan of the universalizing tendencies in design in both its aesthetic and political registers. On this count, Justus Nieland has remarked that "Eames-era modernism often overlapped with the rationalist geopolitical agenda of modernization theory. It often tacitly assumed or overtly endorsed postwar modernizers' specious assumptions about a universal human subject with constant needs and desires."53 Nils Gilman takes Constantinos Doxiadis's project as an archetypal case of such rationalist overreach. Doxiadis's Ecumenopolis: The Inevitable City of the Future, published in 1975 (although it was more than a decade in the making), was an ur-example of "social scientific modernism in full cry."54 What Doxiadis took to be "inevitable" was that the modern mind would optimally engineer cities relative to human need and environmental limitation by construing both scientifically, that is, by abstracting aggregate data from individual cases. Doxiadis was certain of his forecast, for his method — his science of the future, "ekistics" — was grounded in large-scale patterns, in "universal desires," as he put it, and not "individual ones."55 In modernization theory, such certainty trails on "the legacy of New Deal social engineering and technocratic experiments," as Nieland says, practiced now abroad, "with undeveloped postcolonial states as the 'third-world analog to the welfare state.'"56 For modernization theorists such as Walt Rostow and Max Milikan this was a matter of scaling, the favored technique of design-mindedness: "to understand the third world," they believed, "American scholars had to understand their own nation, and these projects were best performed simultaneously." The Cold War scale, sliding only from liberal democracy to state communism, would lose its suasion when "the automatic transfer of concepts from our own round of life" to the so-called third world led to disaster in the Vietnam War.57

Here we might return to where we started — comparing the two versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much — and note that the interwar version of Hitchcock's tale was a spy conspiracy set within the system of European states, but the postwar remake very pointedly expands the geopolitical terrain to include the postcolonial world. It begins in Morocco, where an Indianapolis doctor is traveling with his family by bus to Marrakesh. Its opening shot frames an idealized American family — Doris Day to the left and Jimmy Stewart to the right, their son safe between them — before the camera dollies out and reveals rows of women in veils and men in turbans. Their son is very alive to the landscape outside the bus windows, though he does not deem it foreign but familiar: "You're sure I've never been to Africa before?" he asks his dad. His mom tells him he "saw the same scenery last summer driving to Las Vegas." In this comparison between Las Vegas and the Moroccan desert lies the suggestion that the American ingenuity responsible for the former might be put in service of the latter. The hubris of this belief, too, characterizes Jimmy Stewart as a can-do American and an ugly American all at once. He has apparently told his son that he "liberated Africa," but when his son repeats this in public his father must back off the self-aggrandizing claim. "Well, I was stationed in Casablanca at an army field hospital during the war," he concedes. He has misrepresented his personal history, which Nils Gilman claims is precisely what bedeviled modernization theory. "If modernization theory was perceived to be wrong about how to transform the world," Gilman writes, "it was because it was wrong, in the first place, about how it understood its model for development, the contemporary United States."58 At the edges of Doris Day's and Jimmy Stewart's self-representation is a sense that they are not magnanimous globetrotters spreading culture at the London Palladium or medical knowledge at a Paris conference, but rather they are next-generation colonizers. When Doris Day tells her son they are not "really" in Africa, but "French Morocco," Jimmy Stewart corrects her — "Well, it's Northern Africa" — as if to register, only begrudgingly, that European colonialism was not entirely a square deal.

This buried suggestion of modernization theory is brought to the surface when the couple meets the Laytons (conspirators, we soon learn) at a restaurant. Mr. Layton, whom his wife describes as "a big noise in the Ministry of Food during the war," has come from England as part of "United Nations Relief." He's "preparing a report on soil erosion," he explains, because parts of Morocco are suffering the same failed approaches as America did during the Dust Bowl. Mr. Layton is lying, of course; he's not a UN consultant but a conspirator visiting Morocco to recruit an assassin. But just as Hitchcock makes Eve Kendall an industrial designer to thematize the underlying concerns of North by Northwest, he here uses Layton's cover story to draw forth a concern anchoring this movie, namely, how design crosses cultures. This is played for a joke with Jimmy Stewart, whose ugly Americanism is enacted in his failure to fit his gangly body to the cushioned seats in the restaurant. Is the seat designed for a smaller body, or is he just clumsy? Whatever the case, his inflexibility has graver purport when he tries to follow table manners. First he cannot tear off a piece of bread, then he struggles to eat the chicken with only his right hand, as Mr. Layton has said he must. Stewart wonders why he must limit the hands he uses to dine when it's clearly a sanitary measure, and he doesn't have the instinct to cooperate with his wife to pick apart the bird together. While he imputes a design flaw to this foreign culture, the scenario in fact leads us to diagnose a flaw in his own domestic relations. His wife is a renowned singer who forgoes her career because he will not move his medical practice somewhere with music venues, such as New York City. What Stewart cannot accommodate, hence, is a different set of designs for domestic relations: If he and his wife could cooperate on eating a chicken together, they might coordinate their careers too and not therefore face the prospect of a broken home, symbolized here in their son's kidnapping.

I don't mean to suggest that Hitchcock is criticizing patriarchal society in postwar America, nor the postcolonial implications of modernization theory, but rather that it is the nature of his narrative operations, as Fredric Jameson argues in "Allegorizing Hitchcock," to draw into their snare a "core of purely material and anonymous" forces structuring "daily life" — of which, Jameson says, our "unconscious" is "poorly informed" — and these forces can "vehiculate within themselves a whole cluster or constellation of significant themes."59 I suggest instead that insofar as Hitchcock is concerned with design problems — thematized here in the form of food production, urban planning, domestic arrangements, and so on — he is directing this concern inward (at the model of production) and solving them at the level of film form. If The Man Who Knew Too Much seems to track modernist problems in other fields, it is in hopes of rendering them aesthetic. Hence I have referred to the characters as Doris Day and Jimmy Stewart, not as Jo Conway and Ben McKenna as does the movie, because we are encouraged to see them as such (just as Stanley Cavell says we are meant to see Roger Thornhill as Cary Grant in North by Northwest). We are meant to notice Alfred Hitchcock, too, when he joins Day and Stewart before the rear projection of street performers in a Marrakesh square, and we are meant to notice that Bernard Herrmann is billed within the diegesis as the conductor of the "Storm Clouds" cantata at the Royal Albert Hall (figure 28). These are all elements of production rendered aesthetic. Doris Day really was turning away from her singing career to become an actress, and Jimmy Stewart really had been in World War II. The movie operates formally on the actors as real-world referents in order to call attention to its status as a movie. When at the outset it states its problem as "A single crash of cymbals and how it rocked the lives of an American family," it is signaling a problem, perhaps of a social or political kind, but one that it can only solve by aesthetic means. The set piece at the Albert Hall, that is, will be staged through the resources of silent cinema, preserving in the process a set of production techniques being devalued elsewhere in contemporary Hollywood. The entire 10-minute Albert Hall sequence is carried off free of dialogue. Doris Day does not need to speak because Bernard Herrmann will score what is otherwise a visual unfolding of the event (figure 29). It's easy to think of this as Hitchcock's aesthetic credo, given that he had himself moved from silent to sound cinema, and from the British industry to Hollywood, and thus as the latter industry begins to undergo transformation in its production model he reintroduces the aesthetic coherence of the former system.

Figure 28: The composer of the film score, Bernard Herrmann, is also a composer within the diegesis, because the audience is to understand the movie to be a reflection on its own form.

Figure 29. Caption: Bernard Herrmann framed between two cymbals because the movie is visually unfolding between this music cue, which he himself is getting ready to signal.

If, in the same year, Hitchcock made both The Man Who Knew Too Much and its opposite number, The Wrong Man, what we can infer is that Hitchcock, on an equipoise between opposing models of production, namely the industrial model of studio production and the postindustrial model of runaway production, turned to Saul Bass because modern design looked like a mediating term between the two. But if The Man Who Knew Too Much foretells his recourse to design-mindedness, so too does it foretell its genetic flaw. This happens, we might say, because Hitchcock's narrative operations were geared to oscillate between pathology at small and large scale, between, that is, the individual mind and the social system — between, say, Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt (Universal, 1943) or Bruno Antony in Strangers on a Train (Warner Bros., 1951) and the German navy in Lifeboat (20th Century Fox, 1944) or the Nazi spy ring in Notorious (RKO, 1946) — and what this discloses in The Man Who Knew Too Much is that modular problem-solving often solves problems by displacing them. In its plot, for instance, the tension in the American domestic scene, as enacted in the subordination of Jo Conway's career to Ben McKenna's in the name of happy marriage, is in the end annealed by the recovery of their kidnapped son — but the real-world referent is what drives the emergence of second-wave feminism in the '60s. The design of the closed system (here, the ideal family) did not solve a problem in one step before exporting its solution in the next, that is, but rather tamped it down in one moment only to face it in redoubled form later on. Modern design in the Bauhaus tradition, which imagined that a harmonized closed-system might scale up infinitely, was internally limited by the growth rate of the disorder it displaced. A cautionary tale in this regard is Mies van der Rohe's commission in the early 1940s to design the campus of the Illinois Institute of Technology, which he did by restructuring the Near South Side as something of an urban microcosm, a city within the larger city of Chicago, porous at its borders but organized internally in super blocks intermixing green space with steel-and-glass architecture. Displaced in this project, however, were many residents of Bronzeville, the so-called Black Metropolis that featured one of the highest concentrations of African-American businesses.60 This is not to say that Mies's campus spelled the end of the Black Metropolis, but that the modular integrity of the campus is obtained at a social cost.61 My purpose cannot be so capacious as to reckon social cost as such in the design image, nor do I even think that the Hitchcock-Bass movies bear the social optimism of such Bauhauslers in America as Kepes, but the design-mindedness that Bass imparts to Hitchcock's cinema in the moment that its industrial system is giving way suggests that such design philosophy emerges from the very disproportion between unit and whole, between, in this case, the formal integration of the Hitchcock movie and the broad disintegration of the studio system enfolding it.

Jeff Menne is associate professor of Screen Studies at Oklahoma State University. He is the author of Post-Fordist Cinema: Hollywood Auteurs and the Corporate Counterculture (Columbia University Press, 2019) and Francis Ford Coppola (University of Illinois Press, 2015).

References

- According to his associates, Hitchcock "hated having to constantly resort" to process shots. But he continued to use them at Paramount because the studio insisted he use their VistaVision format — the singular flaw of which was that close-ups were hard to get without rendering the background unusually blurry — and in doing so he began to accept the challenge of composing within such constraints. The resulting "blend of reality and artifice" became "a hallmark of his style," hence what I call his "odd affection" for them. See Patrick McGilligan, Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), 495-496. [⤒]

- The Marrakesh shots were not stock footage, but were actually taken by Hitchcock on location. In "The Making of," art director Henry Bumstead explained the method: "Hitch was a master of going on location and getting all the long shots and everything. In other words, he gets the meat on location, and then gets everything else back in the comfort of the stages." [⤒]

- See "The Evolution of the Language of Cinema," What Is Cinema?, Vol. 1, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), for Bazin's account of what I am calling the "techno-aesthetic" history of the medium. He describes the mix of location shooting and deep-focus photography culminating in Italian Neorealism in a series of essays including "An Aesthetic of Reality: Cinematic Realism and the Italian School of Liberation" in What Is Cinema?, Vol. 2, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005). [⤒]

- Hitchcock had cast Bergman in a sequence of movies in the 1940s, including Spellbound (United Artists, 1945), Notorious (RKO, 1946), and Under Capricorn (Warner Bros, 1949), before she became enamored of Roberto Rossellini's movies and began a professional and personal relationship with him between 1949-1955. [⤒]

- Part of Hitchcock's legend, spread by his crews, was that he envisioned his films in advance and shot them in such an exact amount of footage that the films could only be cut together one way. Saul Bass would only echo this when he said, "He had the whole film in his head. He knew what he wanted to achieve with each sequence in advance, so what happened on set, in a sense, wasn't new information." Pat Kirkham, "Reassessing the Saul Bass and Alfred Hitchcock Collaboration," West 86th 18, no. 1 (2011): 65. [⤒]

- Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 16-17. [⤒]

- Ibid., 200. [⤒]

- See Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010) for the elaboration of the sensory-motor breakdown that is first on view in Italian Neorealist cinema. [⤒]

- I take the coinage "cold-war modernism" from David Crowley and Jane Pavitt's exhibit book, Cold War Modern: Design, 1945-1970 (London: V&A Publishing, 2008), which collects essays in support of a 2008 show at the Victoria and Albert Museum focused on the ways the arts were both recruited into, and reacted against, the Cold War. Of the contributors to this volume, Greg Castillo in particular traces the transatlantic history of design, in the migration of Bauhaus ideas to the US, amid the global competition between capitalist and socialist states. See Castillo, "Marshall Plan Modernism in Divided Germany," ibid., as well as his monograph, Cold War on the Home Front: The Soft Power of Midcentury (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010). Such scholarship joins a critical literature on CIA and State Department patronage of Cold War culture, including Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art, trans. Arthur Goldhammer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985); Fred Turner, The Democratic Surround: Multimedia and American Liberalism from World War II to the Psychedelic Sixties (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015); and Greg Barnhisel, Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature, and American Cultural Democracy (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015), and is usefully situated within periodizing debates on "late modernism," influentially theorized by Fredric Jameson in A Singular Modernity: An Essay on the Ontology of the Present (London: Verso, 2013), and carried forward in such studies as Robert Genter's Late Modernism: Art, Culture, and Politics in Cold War America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010). [⤒]

- In "Organicism's Other," Reinhold Martin gives a fascinating account of the ostensible agon between these two modernist orientations, and whether alterity to an internalized modernism is even possible, by detailing the vexed relationship between György Kepes and Robert Smithson, whom Martin respectively casts as the "agent of an organizational regime" and its antagonist. Reinhold Martin, "Organicism's Other," Grey Room, no. 4 (Summer 2001): 34-51. [⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, "Spatial Systems in North by Northwest," in Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Lacan (But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock), ed. Slavoj Žižek (London: Verso, 1992), 63-64. In Žižek's short essay "Hitchcock's Sinthoms" in the same collection, he begins a line of Hitchcock analysis that he seems to complete in The Pervert's Guide to Cinema (ICA Projects, 2006). In the former, he writes that Hitchcock's "extended motifs" do not offer a "common core of meaning" but rather "a signifier's constellation" (126). But in the latter documentary, Žižek pushes through the abstraction of the signifier into the materiality of form. "I think that what we are dealing with is a kind of cinematic materialism, that beneath the level of meaning, spiritual meaning but also simple narrative meaning, we get a more elementary level of forms themselves, communicating with each other, interacting, reverberating, echoing, morphing, transforming one into the other." What I believe Žižek is articulating here is the design element in Hitchcock's cinema. [⤒]

- At the start of "Hitchcock's Sinthoms," indeed, Žižek remarks that the "auteur theory of Hitchcock has taught us to pay attention to the continuum of motifs, visual and others, which persist from one film to another" (125). [⤒]

- Deleuze, Cinema 1, 22. [⤒]

- For an account of Saul Bass's career, I have relied on Jan-Christopher Horak's invaluable Saul Bass: Anatomy of Film Design (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2014). Horak dispels the notion that Bass was a designer who came from the outside into Hollywood by showing that he was in fact involved with the movie industry from the earliest moments of his design career. Bass of course came to be singularly effective in the corporate identity campaigns he developed throughout the '60s and '70s for Bell Telephone and AT&T, Quaker Oats, United Airlines, and the Girl Scouts. See also Jennifer Bass and Pat Kirkham's Saul Bass: A Life in Film and Design (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2011) and Pat Kirkham's work on Bass in general, much of it in Sight and Sound. Kirkham's essay "Reassessing the Saul Bass and Alfred Hitchcock" in West 86th 18, no. 1 (2011), 50-85, has been particularly valuable for the present essay. [⤒]

- Justus Nieland uses this quote from Kepes's Language of Vision as he maps Kepes's design philosophy onto Rudolf Arnheim's film theory to demonstrate that Arnheim's film-theoretical formalism gained a historical specificity within the discourses of postwar design. See Justus Nieland, Happiness by Design: Modernism and Media in the Eames Era (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 295. [⤒]

- Saul Bass also designed one-sheets and credit sequences for Otto Preminger's movies, notably The Man with the Golden Arm (United Artists, 1955) and Anatomy of a Murder (Columbia, 1959), but it's not apparent to me that Bass's design ideas did anything to inform the visual character of Preminger's movies, which, in my view, are more dramaturgical than graphic in their orientation. Preminger's movies, that is, particularly the aforementioned, seem in keeping with the stage-based realism associated with Elia Kazan and the Actors Studio. [⤒]

- Patrick McGilligan, Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 703. [⤒]

- François Truffaut, Hitchcock Truffaut (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983), 240. [⤒]

- McGilligan, Hitchcock, 533. [⤒]

- Hitchcock and Bernard Herrmann began another collaboration, on Torn Curtain (Universal, 1966), but Herrmann quit the movie after he and Hitchcock disagreed. Their disagreement over the score arguably stemmed from the pressure Universal was putting on Hitchcock to change with the times. See McGilligan, Hitchcock, 673-674. [⤒]

- See the documentary Something's Gonna Live (Raim, Adama Films, 2010), which surveys the work of production designers Robert Boyd, Henry Bumstead, and Al Nozaki. [⤒]

- For an instance of scholarship on Hitchcock and German Expressionism, see Richard Allen, "Expressionism," in Hitchcock's Romantic Irony (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007). Scholarship on the Bauhaus is booming. I have relied on Magdalena Droste's Bauhaus, 1919-1933 (Taschen, 1993), Hans Maria Wingler The Bauhaus: Weimar, Dessau, Berlin, Chicago (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1969), Kathleen James-Chakraborty, ed., Bauhaus Culture: From Weimar to the Cold War (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006), and Reyner Banham's chapter "Germany: Berlin, the Bauhaus, and the Victory of the New Style in Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1980). [⤒]

- Horak, Saul Bass, 46-58. [⤒]

- Ibid., 53. [⤒]

- On the questions of modularity and scalability, see Reinhold Martin's "Organicism's Other" and The Organizational Complex (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005). In the former, Martin writes, "We are speaking, during the atomic age and the space race, of the scaleless reinscription of the human into a technoscientific milieu that described the universe as a 'system of systems'" (40), and he explains that for György Kepes, the "crystal" functioned as a working "module, an abstract integer, a cipher that encrypted order at all scales" (43). In his latter, full-length study, Martin notes that such "modularity, and the flexibility that it implied, became the very image — and the instrument — of the organizational complex," a term that Martin coins to describe an obsession with system at all scales, from biological to social (5). [⤒]

- See Rosalind Krauss's canonical account, "Grids," October 9 (Summer, 1979): 50-64. [⤒]

- Ibid., 50. [⤒]

- I should acknowledge the importance to this interpretation of Stanley Cavell's essay, "North by Northwest," Critical Inquiry 7 no. 4 (Summer 1981): 761-776. There Cavell dwells on the question of "national importance," though for him this chiefly concerns the marriage of the principals. [⤒]

- See David Crowley and Jane Pavitt, eds., Cold-War Modern, 22. [⤒]

- Martin, The Organizational Complex, 43. [⤒]

- Henry Bumstead makes this remark in Something's Gonna Live. [⤒]

- See Tom Gunning, "In and Out of the Frame: Paintings in Hitchcock," in Casting a Shadow: Creating the Alfred Hitchcock Film, ed. Will Schmenner and Corinne Granof(Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2007) and Brigitte Peucker, The Material Image: Art and the Real in Film (Redwood City: Stanford University Press, 2006), 68-103. On Hitchcock's interest in architecture, Steven Jacobs has pressed the matter in more literal terms in The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock (Rotterdam: nai010 Publishers, 2013), stating at the outset that "this book takes Hitchcock as an architect" (11). [⤒]

- Erwin Panofsky, "Style and Medium in the Motion Picture," in Film Theory and Criticism, 5th edition, ed. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 290. [⤒]

- Gunning, "In and Out of the Frame," 31. [⤒]

- See John David Rhodes, Spectacle of Property: The House in American Film (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 179-189. [⤒]

- Truffaut, Hitchcock Truffaut, 269. [⤒]

- For a discussion of the UN Secretariat Building see the chapter on curtain wall architecture, "The Physiognomy of the Office," in Martin, The Organizational Complex. The peculiar mark of its modernism, Martin argues, is the "tension between the twin imperatives of flexibility and standardization," which will let architects reinscribe a sense of community (organization man) within the circulating workforce of the large business corporation (95). [⤒]

- Patrick McGilligan, Hitchcock, 578-581. [⤒]

- See my study, Post-Fordist Cinema: Hollywood Auteurs and the Corporate Counterculture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019), 43-46 and 141-148. [⤒]

- For reflections on the role of studio theme parks, including Universal's, see J. D. Connor's "Parkives . . . Tomorrow's Residual Media . . . Today," Flow 17, no. 6, 2013. [⤒]

- See The Pervert's Guide to Cinema (Fiennes, P Guide Ltd., 2009). [⤒]

- As Reinhold Martin understands it, the spatial orientation of human perception culminates in architecture for Moholy-Nagy, but for Kepes advertising comes to guide the consumer-subject as so many "traffic signs" through the "mobile landscape of our environment." In The Organizational Complex Martin writes, "while Moholy-Nagy concluded the sequence of media in The New Vision with an image of a protocinematic new architecture, Kepes concludes his own extension (and revision) of that project with advertisements intended to regulate the flows of a consumer landscape" (63). [⤒]

- This cartoon style had become an idiom of modernist design at this point, as Dan Bashara shows in his study of UPA animation, Cartoon Vision (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2019). For a sense of "good-life modernism," see Mark Jarzombek, "'Good Life Modernism' and Beyond," The Cornell Journal of Architecture 4 (1990): 76-93. [⤒]

- See Paul Rand, From Lascaux to Brooklyn (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996). [⤒]

- Paul Rand, Thoughts on Design (New York: Wittenborn & Co., 1947), 1. [⤒]

- Deleuze, Cinema 1, 17. [⤒]

- Saul Bass's "Thoughts on Creativity," an addressed delivered to the Architectural Panel at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1968. Accessed at https://archive.org/details/clcmar_000078 [⤒]

- Ibid. [⤒]

- For an account of the liberal consensus, as propounded by midcentury historians and social scientists, see Nils Gilman, Mandarins of the Future (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), 56-68. [⤒]

- Horak, Saul Bass, 218. [⤒]

- Ibid., 221. [⤒]

- Ibid., 66-70. [⤒]

- Nieland, Happiness by Design, 31. [⤒]

- Gilman, Mandarins of the Future, 203. [⤒]

- C.A. Doxiadis and J.G. Papaioannou, Ecumenopolis: The Inevitable City of the Future (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 1974), 2. In the preface, Doxiadis says his book answers "some basic questions about what the City of the Future will be like, not just in the form of a series of hypotheses — which they were at first — but as conclusions about which we can be certain" (xiv). This assertion of future certainty strikes me as emblematic of the confidence of social scientific modernism in the midcentury. [⤒]

- Nieland, Happiness by Design, 31. [⤒]

- Gilman, Manarins of the Future, 207-208. [⤒]

- Ibid., 205. [⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, Signatures of the Visible (New York: Routledge, 1992), 108-109. [⤒]

- See St. Clair Drake and Horace R. Clayton, Black Metropolis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). [⤒]

- For a powerful reckoning with that social cost, see William Julius Wilson, When Work Disappears (New York: Vintage, 1997), 19-20. [⤒]