Decolonize X?

1

In 2019, Eve Tuck remarked that were she to write her landmark co-authored essay, "Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor," now, she might change its "catchy, sticky" title to "Decolonization Is Not Only a Metaphor." The change, she added, would signal that "metaphors are actually really important to how we understand and describe colonialism and decolonization."

Here is where this cluster enters. How do metaphors help us to understand or, conversely, reinforce the contradictions and incommensurabilities produced by colonialism and capitalism?

Though each essay offers different answers, they all share Tuck and Wang's concern for how decolonization, after it's been absorbed by the US academy and corporate culture, becomes an incongruous slogan, a neoliberal buzzword that means little more than the diversification of the syllabus, the curriculum, the canon. As Tuck explained, "when it is used only as a figure of speech, decolonization as a discourse recenters whiteness, resettles theory that is yearning to break the mold, extends innocence to settlers, and entertains a settler future."1

Readers will likely be familiar with such slogans from the summer of 2020, when the struggle for a world where Black life matters leapt from the streets onto corporate websites, publicity campaigns, and advertising materials. As protesters were gassed and beaten, as statues came down, as impromptu public memorials went up, statements were drafted, edited, marketed, posted, shared, circulated, and reproduced.

Often, they risked nothing more than acknowledgment and recognition. Often, they made no commitments; connected no historical, political, economic, or social dots; offered no analysis; made no plans for restitution, reparations, or the return of stolen land. Often, they said Black Lives Matter but said nothing about abolishing campus police or the correctional facilities that sold them the chairs their students sit in, or about their institution's role in gentrification. Often, they sounded triumphalist, complicit, insulated, and harmless all at once, as though their authors were somehow oblivious to the violences that make life at this present conjuncture possible for some but impossible for many.

Though these declarations became commonplace for corporations (including the modern US university), for the most part they have not entailed even the most basic investments in protections for the security of the workers who make them run. In universities, these workers include custodial, dining, and office staff, groundskeepers, graduate and undergraduate student workers, and contingent faculty. As with prominent recent cases of academics "playing Indian" or engaging in other acts of fakery, too often institutions embrace the discourse of decolonization only to enact what Tuck and Wang call "moves to innocence" that aim to assuage, if not resolve, the anxieties of non-indigenous people and institutions alike. But just as these contradictory desires are not commensurable, these anxieties are not resolvable. This cluster suggests that literature and film might help us to better understand that irresolution.

The call to "decolonize x" has proliferated at least since the success of Ngũgĩ Wa Thiong'o's Decolonizing the Mind, published in 1981. Today, "x" runs the gamut from therapy, yoga, diversity, Thanksgiving, Columbus Day, and dieting to the museum, the university, the curriculum, the syllabus, the classroom, the humanities, the digital humanities, and individual disciplinary fields (critical theory, environmental studies, gender studies, literary studies, queer theory, sociology, trauma studies). Calls to decolonize now include "the modernist project of decolonization."2

Scholars and activists regularly point out that, in appearing to suggest that everything can be decolonized, this discourse tends to displace subjects and participants alike, distracting us from needful attention to our relations with the lands and waters we all depend on. The here-and-now of decolonizing discourse should entail regard for the turbid particularities of colonialism; instead, these distinctive processes recede into a vague discursive stream. At the same time, material questions of rematriation, indigenous sovereignty, and indigenous futures are re-contained by non-indigenous institutional projects whose will to preservation — doing what is in the institution's interest — will, by design, override indigenous needs and desires.

The essays collected here suggest that literature and film that engage a decolonial politics remind us there is no programmatic, axiomatic, stable, or coherent definition of what decolonizing means.3 That definition entails an inevitable "struggle over meaning," in Nick Estes's words. The metaphors decolonization occasions must be continuously worked out and remade. Through appropriation and disappropriation, literature and film participate in the struggle over meaning so variously that, at the very least, they remind us how our metaphors may molder — how incurious, unimaginative, and stale they may become.4 At the same time, the works of art this cluster turns to teach us that the meanings of this struggle will always exceed their objects.

For critics and artists alike, in other words, decolonization requires metaphor-making and metaphor-breaking. As Hadji Bakara observes, "metaphor is the generative ground where critics act as world-makers in their own right, participating in the ongoing construction of the 'global.'" It is because they install and make evident "particular relations of force and asymmetries" that our metaphors matter, do damage, open possibility, and require reassessment. When our metaphors neutralize and obscure power relations, they do more than depoliticize and dehistoricize us. They bury us in discourse. They render our language inert and our thinking bloodless. They leach the sourness, salt, vehemence, and exorbitance of life from us.

And yet, as Sylvia Wynter insists, decolonization is about our metaphors. It is about the initiating, transformative work of making and sharing language and art. Decolonial art registers that so long as language serves as an emblem of how far people have been drawn into inhumane and brutal arrangements of social life, so too language will serve as a creative, world-making, breath-giving force of reckoning and remembrance drawing us back toward humane limits.

***

What does the imperative to decolonize x mean in actuality for writers, filmmakers, and readers of Post45?

Studies published under the Post45 imprimatur have analyzed the post-1945 period in terms of institutionalization, conglomeration, and financialization. They have offered strong accounts of how literature participates in capitalism's institutional articulation — through economies of prestige, the soon-to-be Big Four, the university, the proliferation of cultural mechanisms for laundering out the stench of capital — and the changes wrought in the new gilded age of Amazon and Google. But rarely do these accounts, whether data-driven or text-driven, whether formalist or comparatist, sociological or historicist or historical materialist, or some of all of the above, reckon with US cultural production as that of an empire. Rarely do they address the imperialism of the publishing industry, of corporations, of the university — and by extension, how works of art and criticism emerge from empire.5

To put it bluntly: one reason for "literature's vexed democratization," to borrow the title from Claire Grossman, Juliana Spahr, and Stephanie Young's recent article in American Literary History, is that the post-45 US literary field is sustained, often opaquely and obliquely, by the political economy of a territorial empire. Think of post-45 US literatures as multilingual literatures of empire. Unless we want to ignore the distinctive, multilingual, archipelagic histories of American Samoa, Guantanamo Bay, Guam, Hawai'i, the Northern Marianas, the Panama Canal Zone, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Saipan, the US Virgin Islands — to say nothing of the overseas presence of roughly 800 US military bases, to say nothing of the histories and ongoing practices of US interventionism — then we need to keep in view, as Arjun Appadurai insists, that "the relevant issue remains rich versus poor, i.e. North versus South." The literatures of the US have rarely, if ever, been made in a democracy. They cannot be democratized. They cannot not be vexed.

Minoritized artists know this well, because they do the essential, leavening, metabolizing work of art-making without the power of the nation-state behind them. Though fully integrated as workers, as political subjects such artists remain only partially incorporated into Western constructions of political modernity, such as Americanness or global citizenship — even when, as Spahr has shown, they are subsidized by the state, the university, or an economy of prestige (or all three). They write in an empire that is against them. Their work is often tenuous and tensile, more ferocious, dynamic, and blooded, because it originates in this jeopardy.

***

This cluster springs out of two questions. First, what is the relationship between historical decolonization — and specifically what historians call the era of global decolonization, roughly a thirty-year post-45 phenomenon that transformed the global economic and political order — and contemporary cultural practice that occurs under the sign of the decolonial? Second, what is the cultural logic of the ubiquitous call, as the poet Farid Matuk puts it, to "get back on the hook of decolonizing everything"?

The essays revolve around these questions, whether by tracing the itinerary of decolonial thought through Chicanx historians and José Antonio Villareal's bildungsroman Pocho (as in José Antonio Arellano's contribution) or through the attempt, in the lauded Brazilian film Bacarau, to decolonize the Western (in Emilio Sauri's provocative essay). Antonio Arellano and Sauri are notably critical of both academic and popular efforts to decolonize x. For Antonio Arellano, the discourse of decolonization obscures the "material causes, the specific economic and political contexts, of historical change and contemporary problems." The proliferation of this discourse isn't problematic in and of itself, however. Our syllabuses, curricula, museums, and fields of study should be more diverse and inclusive. What's at stake, rather, is what we don't talk about when we talk about decolonizing.

Antonio Arellano shows that decolonization emerges in the late 60s and early 70s as a political discourse emphasizing "inclusion, ownership, and cultural pride" as solutions to the unsolvable economic problems facing Chicanos. Ultimately, this antiracist discourse did not help Chicano workers improve the conditions of their lives. Then, as now, Latinx workers cannot count on access to living wages, job security, food security, and quality housing, health care, childcare, and education as givens. Instead of ameliorating these problems, too often decolonizing discourse has narrowed the meaning of struggles to absolve them from the ongoing collective fight against economic exploitation and the unequal division of labor everywhere to a domestic fight against discrimination and exclusion. Both battles matter, Antonio Arellano concludes, but for too long the meaning of decolonization has been dominated by contests over proprietorial, monolithic notions culture and identity.

Emilio Sauri's essay extends this critique to Bacarau, revealing the film's logic as one that "treats class as an identity like race and gender," such that what the film defines as offensive becomes "how the poor are viewed" rather than the conditions that sustain their immiseration. Though Bacarau gives us what we want — the Western turned on its head, a bloody and victorious uprising against white supremacy — Sauri points out that by the film's end the villagers remain poor and water remains scarce. Nothing about the precarity of the villagers' economic situation has changed. What is supposed to have changed, rather, is us, the viewers and consumers of the film. More specifically, our view of the villagers is meant to now entail a new recognition of the dignity of the lives lived by the town's inhabitants.

Sauri contends that what's wrong with this sleight of hand is analogous to what's wrong with the academic theory of decoloniality — at least the most well-known version of decoloniality in the US, which draws extensively on Aníbal Quijano's influential idea of the "coloniality of power." As Sauri puts it, "Redefining decolonization as 'epistemic disobedience,' decoloniality . . . makes the problem of poverty into a matter of freeing its millions of victims across the globe not from the political and economic structure that engenders such indigence, but from the perspectives and attitudes that would deny the dignity of those victims instead." Sauri concludes that, as an allegory, Bacarau suggests that full integration into contemporary global capitalism means submitting to a new kind of "aesthetics of humiliation" and "neo-backwardness."

The other two contributions to the cluster make a diptych of sorts. Philip Tsang's essay reinvigorates longstanding debates around the global anglophone novel and formalism by examining the "enigmatic forms" of Zadie Smith's decolonial formalism. Such forms disclose an inassimilable alterity that attracts and repels by turns. "Cambodia" in Smith's fiction names, for Tsang, not a toponym nor a nation-state but the ambiguous, charismatic, estranging presence of the denied other. The confrontation between the unmappability, portability, and opacity of the Global South's enigmatic forms and desirous readers of contemporary global fiction situated in the North is Smith's lasting theme.

In her reading of R. Zamora Linmark's irreverent novel Leche, Kelly Roberts argues that "a flat, celebratory inclusivity is not the destination, but just part of the baggage that comes with reading global anglophone fiction across networks defined by imperial and neocolonial power relations." Whereas Tsang finds portable forms in the London of Smith's "The Embassy of Cambodia," Roberts insists on the limitations of portability in the Manila of Linmark's novel. The many detoursof Leche, rather, insist on the "irreducibly specific" aspect of the Philippines. Roberts locates this aspect in the novel's "unfixed and shifting" second person address. Its "you" gaily shifts between different addressees — tourist, a decolonization beginner, a balikbayan, like the protagonist Vince, whose return to the islands is the novel's occasion.

In paying attention to how Linmark's novel "re-make[s] subjects as historical actors," Roberts's essay provides the most nuanced account of what it means to consume decolonial artworks. Leche cannot be read straight: its divagations, by turns scathing, by turns laugh-out-loud outrageous, require not just reflection, but a kind of ongoing, intestinal gut-check. This process is an inherently political activity, Roberts insists, because it requires "that . . . readers develop a more sophisticated sense of geopolitical direction, one in which being implicated and being included do not necessarily map neatly onto one another." To understand Linmark's novel as decolonial means reckoning with the demands of Leche's changeful address. As readers we ourselves must be undone and remade.

2

The cultural logic of decolonial poetry is refusal. This logic connects the de- of Linmark's de-tourism with the queer decolonial impulse of turning away that echoes throughout the work of so many artists, from the radical women of color of This Bridge Called My Back to the contemporary trans Puerto Rican poet Raquel Salas Rivera.

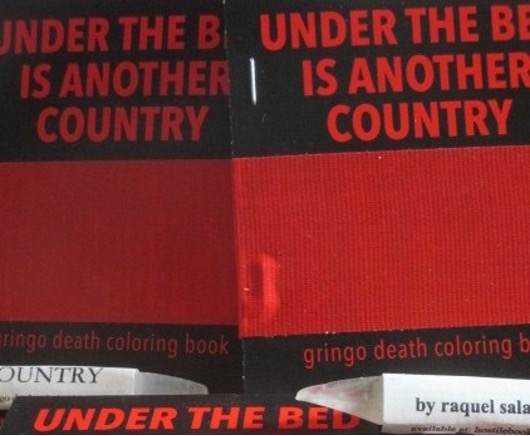

At the 2017 gathering of the Association of Writers and Writing Programs, the small press writing collective Hostile Books displayed Salas Rivera's chapbook UNDER THE BED IS ANOTHER COUNTRY: gringo death coloring book. The chapbook, however, was not for sale.

In an interview with Sarah Timmer Harvey for Asymptote, Salas Rivera calls these taped-shut chapbooks "closed objects." The collection, in his words, "deals with Hurricane Maria and the distance between the translated and the translating self."

On the one hand, Salas Rivera's "closed objects" deny the activities and pleasures of browsing, skimming, and all the other kinds of reading consumers do as we consider purchasing a book. Their closure rejects the colonialist assumption that everything, including post-Maria Puerto Rico and its subjects, are or should be limitlessly accessible, available, explicable, knowable, translatable, and transparent. On the other hand, the book that that chapbook became draws the activities of reading and consumption into an intimate, public, uneasy, and unresolved relation, raising the question of what kind of opening or breach, if any, decolonial works of art make in captive relations of contemporary life, and what those openings do. This question is especially salient when the artwork strategically cues us to read it not — or not only — as resistance to a recognizable object or antagonist. How should we understand the decolonial artwork that does not take a position against a dominant or define itself in the terms of what it is against or what is against it, but instead refuses the object altogether?6

Such a refusal, to be sure, issues a challenge to the hermeneutic repertoire undergirding any interpretive endeavor. It circumvents the ingrained disciplinary procedures many of us take for granted: the intensive process — often described in terms of compulsion or obsession — of taking, constructing, or privileging of an object of analysis; the capitulation to the preconceived norms and conditions of bounded, disciplinary thinking as such; the notion of inquiry as an exclusive domain of reasoned determination, distinction, and delineation; and the formalist closures that cut off more troubling inquiries into the relational origins of shared debts and pleasures.

The mode of refusal at work in Salas Rivera's cuir decolonial poetry is at once a turn away, not back or toward, and a refusal to turn around. It summons a different relation to the social and distributional inequalities that structure the conditions under which we become addressable to one another, and therefore changes the very social grounds on which the terms of recognition depend. It is an activity of the condemned, the unproductive, the wretched of the earth, and, as Deborah Vargas suggests, of lo sucio, of the queer surplus that is "too black, too poor, or too sexual," whose "dirty and filthy nonnormativity" today contaminates contemporary neoliberal projects and heightens capital's contradictions.7

Salas Rivera's poetry intimates that this opening the artwork makes might be most provocatively and usefully thought of as a hole — or rather, many little holes — huequitos or "holies," in his ludic self-translation, made in the languages of empire: recurrent gay puncta in the aftershocks of colonial disaster. The figure of the "huequito" appears throughout his work as a figure of grief-within-pleasure and pleasure-within-grief: it is the title of a series of poems grieving multiple tragedies — the murder of the poet's friend Iván Trinidad Cotto, the Orlando PULSE massacre, in which 23 queer Puerto Ricans died — Puerto Ricans, as Salas Rivera observes, who were there that night in part because they were displaced by the debt crisis. The poems likewise grieve over the subsequent passage, that same year, of the PROMESA legislation and the establishment of la junta, or the financial oversight and management board.

In "huequitos," Salas Rivera further elaborates the queer dimension of his poetry by articulating an unstable distinction between lo cuir and queer:

the difference is the difference between knowing and not knowing IVÁN. the difference is in how we touch, where we touch, and how much is seen. the difference lies in the internalized imperative to code my language, how closeted i feel or how unfreed by the imperialism of u.s. freedom. the difference is the water between san juan y orlando. the difference is crossing over because of a debt imposed by predatory investors, only to be met with the hatred of a country that never sees us except as an electoral statistic or a token latinx. the difference makes little holies in every poem . . . huequitos i curl up inside. holies i want to suck and shiver

Following Salas Rivera and his sometime interlocutor, Wendy Trevino, I suggest we think of decolonial poetry as an activity of speaking through and across these little holes. On the edge of discernibility, these self-estranging pierces become unfillable, contingent little heterotopia piercings made of the distances between languages and water, apertures where desire and eros and sex can thrive ("suck and shiver") protected from cultural hatred, the predations of banks, "the imperialism of u.s. freedom," and the bankruptcy of electoral politics and the liberal faith in reform.

I interpret these diminutive holes as zones of address, endearment, conviction, and risk. They are also, to borrow a term from Urayoán Noel, "diasporous": protean, recombinant, vulnerable, and highly mediated, they are spaces of becoming that confront the contradictions and betrayals of circulation. Salas Rivera's description of what it was like to return to Puerto Rico at age fourteen after living in the US helps us to understand this address as "decolonial," or more precisely, as decolonizing:

I don't think there is a way of transmitting the difference between living in the metropolis and living in the colony. I can only describe what I underwent as decolonization. I take the term decolonization to mean learning dis-dominance. It is not a mental or spiritual process that can be divorced from a struggle against the economic project that is U.S. imperialism.

In Salas Rivera's work — and we could add that of many other poets, including Rosa Alcalá, Dionne Brand, Julieta Paredes Carvaja, Don Mee Choi, Joey de Jesus, Harmony Holiday, Bhanu Kapil, Alan Pelaez Lopez, Urayoán Noel, Farid Matuk, Mara Pastor, Craig Santos Perez, M. Nourbese Philip, Jennif(f)er Tamayo, Wendy Trevino, Solmaz Sharif, Layli Long Soldier, and Sara Uribe — the struggle to learn and practice dis-dominance is disclosed through the ongoing, dramatic reorganization of relations (potential, imagined, articulated, withheld) the poems convoke. These relations are remade through the poems' self-reflexive inquiry into the matter that occasions them and makes them possible. Their reorganization necessarily disrupts what Francoise Lionnet and Shumih Shih call "the metonymical relationship between language and nation."8 Rather than an unqualified embrace of the limitless possibilities and freedoms of the imagination, this work's refusals necessitate an ongoing meditation on the unequal conditions out of which poetry arises.

***

The same year the book-length version of While They Sleep: Under the Bed Is Another Country was published, another project, Puerto Rico en mi corazón, a coedited and cotranslated bilingual anthology of Puerto Rican poets writing in the "meta-diaspora," appeared from Anomalous Press. Along with printed broadsides, the anthology raised funds for survivors of Hurricane Maria. Salas Rivera and his co-editors describe their project not as an "anthology, but a hole in our hearts through which the voices around us — and those we strain to hear — rush with astounding force. These voices make an ensemble," they write, "whose chorus is yes." This framing rejects an understanding of translation that relies on notions of equivalence, or establishing equality within a binary, as in "source" and "target," or in Lawrence Venuti's well-known terms, "domesticating" and "foreignizing."9 They reject the notion that the meaning of a translation lies in its supplementarity or adjacency to an "original." Likewise, they reject the notion of anthologizing as a curatorial or canon-making activity, including one that is counter-canonical (as is the primary function of the Latina/o anthology in Raphael Dalleo and Elena Machado Sáez's influential account of the making of the Latina/o canon).10 Their anthology, in other words, turns away from cultural capital, taste-making, and economies of prestige.

Instead, like the economy that the storm produces, the anthology and its translation are about inequality. Speaking about the anthology with Annie Won in Critical Flame, Salas Rivera explains his theory of translation this way:

I like to quote this moment in Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist's translation of Mikhail Mikhailovich Bakhtin's The Dialogic Imagination: "[P]rior to [the] moment of appropriation the word does not exist in a neutral and impersonal language [ . . . ] but rather it exists in other people's mouths, in other people's contexts, serving other people's intentions." Language exists in mouths, in the materiality of its being spoken. This means that Spanish as it is spoken in Puerto Rico relates to English on unequal terms because most Puerto Ricans on the island don't speak English, and because English was a language the colonizers attempted to impose. It is important to recognize and contextualize this inequality before translation.

Salas Rivera's remarks present Puerto Rican Spanish as a creative, persistent, transgressive molten force of Puerto Rican social life, a vernacular that is inimical and, often, untranslatable. Confronted with "inequality before translation," translation and anthologization constitute a collaborative and ferocious yes, affirmative practices "reflective," the editors write, "of our own connections, our own positions, ready for new configurations."And in that readiness, as the title Puerto Rico en mi corazón reminds us, they turn to the example of the Young Lords. They use anthologizing and translating to ask what that slogan might mean in the present; and to build alternative histories of the impossible desires — for justice, for equity, for vida — that reverberate today.

Salas Rivera's recent "ataúd abierto para un obituario puertoriqueño" ["an open casket for a puerto rican obituary"] is dedicated to Pedro Pietri, who performed "Puerto Rican Obituary" in during the Young Lords' takeover of the First Spanish United Methodist Church in East Harlem. As in Pietri's anticolonial obituary poem, in Salas Rivera's "open casket" Juan, Miguel, Olga, Milagros, and Manuel, work, pay rent, and "prepar[e] their taxes." Unlike Pietri's Puerto Ricans living through the crises of deindustrialization and urban renewal in 1970s New York, however, Salas Rivera's live the "aftershocks" of colonial disaster: the ongoing failures of U.S. regulation and control, from the Jones Act and Operation Bootstrap to the crises of modernization, debt, Hurricane Maria, and the junta, playing out today. Salas Rivera's poem finds Puerto Ricans bregando, making do, gigging, getting by, getting it, hitting it, acting trash, sharing, swearing, helping, hurting, inventing, and much more. The poem begins:

trabajaron con una rosa entre los dientes.

trabajaron en el turno de las tres, cerrando borracheras,

chingando entre cajas.

fumaron. a veces se acusaban de jalar duro. a veces no se

respetaban.

cuando iban a la feria, al otro lado de plaza,

comían nubes maybelline y cerraban los ojos a ciudades frías.

perdían tíos y no hablaban de funerales.

muchas veces se reían cruelmente de la lluvia sucia.

pagaban la renta sin contrato.

era lo único quizás estable, aunque titubeaba el cheque.

they worked with a rose between their teeth.

they worked the three o'clock shift, closed drunken nights,

fucked between boxes.

they smoked. sometimes they accused each other of hitting it

too hard. sometimes they acted trash.

when they went to the fair, across from the plaza,

they ate maybelline clouds and closed their eyes on cold cities.

they lost uncles and didn't discuss funerals.

often, they laughed cruelly at the dirty rain.

they paid their rent without a contract.

this, the only maybe stable payment, even if the check

stammered.

As this list suggests, inside Salas Rivera's "open casket" are everyday performances of the uncontainable, performances that make life in Puerto Rico livable as the "imperial hustle" of "surprise, crisis, rescue" goes on and on. And unlike Pietri's dead Puerto Ricans, Salas Rivera's know they are Puerto Ricans. They die almost as often of laughter as of colonialism.

***

What is perhaps most noteworthy is the way this poetry's return to the late 60s and early 70s occurs within a structure of address left productively uncertain and burdened with interpretation, such that, to borrow a phrase from Sianne Ngai, its uncertainty "prepares the way for agonistic thinking." We are asked to think agonistically, above all, about the situation and activity of reading. In the "About" section of its Tumblr, Hostile Books describes itself as "a collective of writers invested in the exploration of strategies for complicating (or otherwise making perilous, hazardous, or toxic) the activity of readership." Its slogan is simple: "Hostile Books bite the hand that reads them."

Decolonial poems that engage with reading, and particularly the reading of poems, explicitly provoke this kind of thinking. One of the early poems of Wendy Trevino's Cruel Fiction, for instance, titled "Poem," wryly rewrites two of Frank O'Hara's most famous poems:

Santander Bank was smashed into!

I was getting nowhere with the novel & suddenly the

reader became the book & the book was burning

& you said it was reading

but reading hits you on the head

so it was really burning & the reader was

dead & I was happy for you & I had been

standing there awhile when I got your text

Santander Bank was smashed into!

there were barricades in London

there were riot girls drinking riot rosé

the party melted into the riot melted into the party

like fluid road blocks & gangs & temporary

autonomous zones & everyone & I

& we all stopped reading

And here is Frank O'Hara's "Poem":

Lana Turner has collapsed!

I was trotting along and suddenly

it started raining and snowing

and you said it was hailing

but hailing hits you on the head

hard so it was really snowing and

raining and I was in such a hurry

to meet you but the traffic

was acting exactly like the sky

and suddenly I see a headline

LANA TURNER HAS COLLAPSED!

there is no snow in Hollywood

there is no rain in California

I have been to lots of parties

and acted perfectly disgraceful

but I never actually collapsed

oh Lana Turner we love you get up

With its series of substitutions — the tabloid headline for a text message; Turner's fainting episode for the destruction of Santander Bank; the playful repartee about the indiscernibility of the New York weather (raining / snowing / hailing) for reading and burning; snowless Hollywood for barricaded London; the New American avant-gardist after party full of "perfectly disgraceful" men for "riot girls drinking riot rosé" in the streets); and the I do this-I do that of O'Hara's urbane simultaneity for the "melting" of party and riot and "fluid road blocks" — Trevino's update gleefully proclaims "the reader" to be "dead"; locates the pleasure elsewhere; and suggests that reading and poetry will, at best, create the conditions in which people stop reading and shopping altogether. Indeed, as you'll notice, the final lines of Trevino's foreshortened poem leave O'Hara's behind, echoing instead the final phrase of O'Hara's elegy for Billy Holiday, "The Day Lady Died," which describes seeing Holiday's picture in the New York Post and ends with an intense somatic memory of listening to Holiday perform:

and I am sweating a lot by now and thinking of

leaning on the john door in the 5 SPOT

while she whispered a song along the keyboard

to Mal Waldron and everyone and I stopped breathing

Trevino's "everyone & I / & we all stopped reading" thus turns away from O'Hara's poetics in several respects. It turns from O'Hara's situation of address — the public intimacy of sharing in Holiday's breath-taking performance; the declaration of popular affection for the fallen figure of publicity — and therefore from the orientation of O'Hara's work toward mass subjects and mass publics. It turns from the cultural logic of celebrity and the renovation of the elegy toward the pleasures of popular unrest. Trevino's poem remains colored by the elegy, but the elegy's energies are now dispersed into mournfulness at the failures of Occupy and the Arab Spring, the rise of the Trump era, and the persistence of multinational banking conglomerates — and, indeed, the persistence of book reading, that specific practice of the reading class, which, Trevino's work intimates, has become what Wendy Griswold surmised: just "another taste culture" among many "pursuing an increasingly arcane hobby" rather than an incitement to direct action.11

This poetry heightens the contradictions. To read it from the North is to ask not just what it means to consume it as a poet, critic, academic, or member of the reading class, but what it means to be addressed by this work as a reader and listener, to be called to take up this burden of interpretation, and read, as it were, from the position of the refused.

How then should we read this poetry of refusal? Contemporary decolonial poetry demands its readers be unequivocal about the limitations of poetry. Poems do not have "unlimited potential"; "not everything [is] poetry," as Salas Rivera writes in Lo terciario / The Tertiary. "No to poetry," Jennif(f)er Tamayo writes in the reissue of YOU DA ONE. "No to me, i am probably an enemy of poetry." Contemporary decolonial poetry is unequivocal in its refusal of the value of the literary, when that value depends on the sloppy amalgamations of the empire behind it: "y en todo somos independientes, / hasta en el hueco más colonizado del temor poroso" ["and in all things we are independent, / even in the most colonized hole of our porous fear"], Salas Rivera writes in "la independencia (de puerto rico)" ["the independence (of puerto rico)." The struggle over meaning is itself redistributed and opened up, not in an expansionist manner, but in the manner that one hole — a huequito in Salas Rivera, the smashed façade of Santander Bank in Trevino, a "cry of art" in Gwendolyn Brooks's "Boy Breaking Glass" — might lead to another, and another, and so might fill with "pepper and light / and Salt and night and cargoes," as Brooks writes, might become a larger hole, or a network of holes, a warren, say, where a fugitive public might gather and conspire.

Before this differentially articulated world-making negativity the interpretive question for the refused is not, as Barthes famously put it, who speaks in this text here, but are you bitten? Are you stung? Are you listening — and what is listening doing for you? Or, as Trevino's poetry asks: Who are you becoming? And who will you say you are?

Scott Challener (@ScottChallener) is Assistant Professor of English and Foreign Languages at Hampton University. He is currently completing two book projects: one on the encounter between U.S., Spanish, and Latin American poetries in the long twentieth-century; the other on the poetry of refusal. His poems and essays have appeared in Contemporary Literature, Gulf Coast, Lana Turner Journal, Mississippi Review, Omniverse, Poetry, The Langston Hughes Review, The Nation, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere.

References

- Tuck here rehearses several key claims of her co-authored essay, which appeared in the inaugural issue of Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society. See Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, "Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor," Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1, no. 1 (2012): 1-40.[⤒]

- "We need to completely reimagine what decolonization can look like," Yarimar Bonilla contends in an interview with Ryan Cecil Jobson for Public Books. "We must create new decolonial visions that can address the common challenges faced by postcolonial societies, because clearly the formulas that exist today—be they constrained independence, some form of annexation, or remaining in an intermediate limbo—have only served to reproduce the inequalities of empire across and beyond the Caribbean. And again, that's not a bug—the modernist project of decolonization has not failed, it is working as intended."

"Though decolonization matters, that we may even face decolonizing decolonization means we must simultaneously go beyond it," Lewis R. Gordon similarly affirms. "We need new ways of thinking, then, that recurring query: What is to be done?" Gordon's answer: "Our imagination, guided by the sober constraints of evidence, is a start." Both Bonilla and Gordon's appeals to the imagination underscore the significance of our metaphors for decolonization.[⤒]

- Some well-known attempts at definition include Walter Mignolo and Catherine Walsh's On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (Duke, 2018), Nelson Maldonado-Torres's "Outline of Ten Theses on Coloniality and Decoloniality," the "Decolonial Aesthetics" manifesto, and María Lugones's work on the "coloniality of gender." All draw on Aníbal Quijano's theorization of the "coloniality of power"; Lugones was motivated to develop a critique of the constitutive heterosexism in Quijano's account.

For alternatives to this line of thought, see the decolonial feminist work of Gloria Anzaldúa, Julieta Paredes Carvaja, Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui, bell hooks, Audre Lorde, Cherríe Moraga, Emma Pérez, and Chela Sandoval, among others. See also the work of Arjun Appadurai, Enrique Dussell, and Achille Mbembe. In a recent review essay, Joe Parker recommends Jodi Byrd, Raúl Zibechi, Jay Johnson and Soren Larsen, Raquel Gutiérrez Aguilar, and Glen Coulthard. Parker persuasively contends that recent approaches on offer in many of Duke University Press's publications, and particularly in its "On Decoloniality" series, "narrowly limit activism to epistemic and pedagogical change" and "reduce decolonization to rhetoric rather than opposing settler colonialism South and North and ongoing colonization in social, economic, political, and cultural terms." "If all we seek is decolonization of the mind," Parker warns, "then we will have already conceded what [Jarrett] Martineau and [Eric] Ritskes call "the loss of the most precious and transformative foundation of decolonization: land and place."

As this essay suggests, I prefer the poets' definitions. [⤒]

- On "disappropriation," see Cristina Rivera Garza, The Restless Dead: Necrowriting and Disappropriation (Vanderbilt University Press, 2020).[⤒]

- An important exception is Yomaira C. Figueroa's work on "Afro-Boricua Archives," which draws from Figueroa's recent monograph, Decolonizing Diasporas: Radical Mappings of Afro-Atlantic Literature (Northwestern Press, 2020). Alexander G. Weheliye's intellectual history of decolonizing critique as it develops through Black Studies appears in a footnote to Aida Levy-Hussen's powerful essay on boredom in contemporary African-American literature. Decolonization, in different strains, also figures prominently in Joseph R. Slaughter and Daniel Elam's contributions to the Extraordinary Renditions and 1990 at 30 clusters, respectively.[⤒]

- I draw on this distinction from Becca Klaver's essay on the feminist poetics of refusal in the Summer/Fall 2019 &Now issue of Notre Dame Review. Klaver in turn draws on Black and queer theorists of refusal, including Jack Halberstam, Fred Moten, and Stefano Harney; Jennif(f)er Tamayo's reissue of YOU DA ONE (Noemi Press, 2017); and the collectively authored feminist refusals of the "No Manifesto," published in the Fall 2014/Winter 2015 Gender Forum of the Chicago Review. My study of the poetics of refusal is also informed by the work of Tina Campt, Saidya Hartman, and the Practicing Refusal Collective; Lauren Berlant, Don Kulick, and Heather Love; and Margaret Ronda and Rachel Greenwald Smith, among others. [⤒]

- Deborah Vargas, "Ruminations on Lo Sucio as a Latino Queer Analytic," American Quarterly 66, no. 3 (2014). [⤒]

- Minor Transnationalism, edited by Françoise Lionnet and Shu-mei Shih (Duke University Press, 2005), 4.[⤒]

- Lawrence Venuti, The Translator's Invisibility: A History of Translation (Taylor & Francis, 1995; 2017).[⤒]

- I refer specifically to Dalleo and Machado Sáez's essay, "The Formation of a Latina/o Canon," in The Routledge Companion to Latino/a Literature (Routledge, 2013). See also their earlier study, The Latina/o Canon and the Emergence of a Post-Sixties Literature (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).[⤒]

- Wendy Griswold, "Reading and the Reading Class in the Twenty-First Century," Annual Review of Sociology 31, nos. 127-141 (2005).[⤒]