David Berman

A rabbi, a real cabbalist, once said that in order to establish the reign of peace it is not necessary to destroy everything or to begin a completely new world. It is sufficient to displace this cup or this bush or this stone just a little, and thus everything.

— Ernst Bloch, Spuren1

Instead of time there will be lateness / And let Forever be delayed

— David Berman, "The Wild Kindness"

Bridges had a special place in the poetics of David Berman's songwriting. They recur in Silver Jews' artwork and album titles, but I mean this too in both the formal and thematic senses that bridges connote. Berman clung to them as the apotheosis of an urban, quotidian, no-place, architectonics whose aesthetic and philosophical potential he evoked in The Natural Bridge cover art, with its distant buildings and shooting star suspended at the turn of a downward trajectory; the precarious wooden bridge at sunset on the cover of Starlite Walker; in the half-lit, transitory, spaces of the dying American West in "Smith & Jones Forever"; in the odd William Eggleston-like Instamatic flatness of the Bright Flight cover art; and in the band's music video for "Random Rules" (where Berman is seen helping an elderly man clear a blocked pathway of snow as an everyday gesture of care in a transitory space). But the bridge was also, perhaps, his signature musical form — the sonically, lyrically, or rhythmically differentiated bars inserted between a verse and a chorus — that have a special relationship to time in either holding us in suspension or propelling us along.

A traditional rock bridge is a transit point we move through to the next thing. Hip hop, funk and jazz have their "breaks" that allow the audience a brief hold on time's inevitable advance — an invitation to breakdancing or other forms of collective and individual expression — but rock's bridges are unusually impatient for The End. The classic rock bridge ferries us to meet the chorus, that stable moment in whose epiphanies one can sometimes feel the nearly evangelical embrace of death's finality. In the hierarchy of rock moments it also has a secondary role in getting us to some place where we can dwell in the complete, but somehow phony, harmony of a collective, cathartic release (itself a kind of death) as the chorus takes us out of the drag of the everyday world.

Even as the chorus functions as release, one gets the sense that to experience catharsis in Berman's aesthetic world would be to turn one's back on the chronic problems of the present. Berman, put simply, lamented the loss of uncertainty the chorus represented and favored the delay of the bridge. As he suggested on "Random Rules", he had a sense that perfect harmony and unity were a site of hazard and hostility to difference: "In 1984, I was hospitalized for approaching perfection," and "I know you like to line-dance / Everything so democratic and cool." The rock chorus is the final incorporation of the individual voice into the total mass; the ecstatic release of the singers-along. The origins of the chorus lie in drama as one of the earliest modes of collective artistic expression, where itwas a mimetic reflection of the social processes of decision and the upholding of conventional values, especially in the cathartic verdicts meted out by the Greek polis. Choruses are judgements. Even after the lyrical turn in Romanticism towards the individual consciousness they still retain an emphatic quality that would sit uneasily alongside the ambiguities of David Berman's aesthetic. They pronounce a final vocabulary of social correctness that opens up the ethical question of who is excluded from their vision. And on "Slow Education" — a work in whose title we have an ideal encapsulation of its philosophy — he sings of singularity and monomaniacal focus as a suicidal precondition: "You've got that one idea again / The one about dying." As one of the rarer moments in his oeuvre in which we encounter an actual, recognisable chorus, this lyric ironizes the song's theme. "Slow Education" proceeds slowly: Berman defers the chorus through its emphasis on the bridge only to then hold back the chorus itself even further with extended vowel sounds and drawled lyrics: "Oh Oh Oh / I'm lightning / Oh Oh Oh / I'm rain." It is, perhaps, the most languorous and least committed lightning and rain ever seen or heard.

Listening to Berman's songs, whose insights have been sharpened to an excruciating point by the tragedy of his passing, we find in the slow delay of his phrasing and the strangeness of the imagery that supervenes at key points a notable absence of the propulsion to finality characteristic of other rock. We are instead made to rest on the bridge and live with him in a state of grace. The bridge in Berman's oeuvre is a site of affectively intense experience where a normative process of ritual transition and incorporation into community is held up: it's also a space of insight, because while one is not fully incorporated into a community, they remain open-eyed to its processes. In this sense, then, Berman's bridges index a postmodern condition whose main attribute is not a waning of affect (as Fredric Jameson would have it) but an escalation of feeling in wilful defiance of entropy. This entropy, crucially, seems like a process of dying, but in Berman's work it is not death properly that confronts us, but its constant foreshadowing — an aesthetic acknowledgement that nothing good can come of a world that either gives up on hope entirely, or propels itself with abandon into simplistic and ignorant visions of the future. Consequently, to have purpose life must be conducted in the shadow of death ("I saw God's shadow on this world," says Berman in "There is a Place"), but cannot have death's fulfillment as the goal. Deferral, then, is the principal purpose of the Berman bridge, which does not occur as a mere stay of execution or in fearful flight from death, but as an aesthetic suspension tout court.

In this moment, life itself has meaning as a place of potentiality in which turns and reorderings of the world are made possible. As he sings on "People" from American Water:

Moments can be monuments to you

If your life is interesting and true

It's just the same for a man or a girl

The meaning of the world lies outside the world

People love people and they understand

If you want to renovate your background mind

Federal woman needs municipal man

People gotta synchronize to animal time

You can't change the feeling

But you can change your feeling

About the feelings in a second or two, aha

People always come around

Here, Berman reasons that in order to find meaningful community and to love people in the aggregate ("it's just the same for a man or a girl") we must acknowledge that the established forms of meaning-making for the world have historically been located "outside the world", yet even that is capable of changing. We "can't change the feeling" but we are capable in this space of "animal time" of changing our "feeling/About the feelings in a second or two." A delay permits a reflection that alters our position in relation to future time, as Ernst Bloch knew well: "in order to establish the reign of peace it is not necessary to destroy everything or to begin a completely new world. It is sufficient to displace this cup or this bush or this stone just a little, and thus everything." Berman imagines an anti-utopian road not taken, or, as he called it a "What is Not But Could Be If" from Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea (before a line about "crossing this abridged abyss" no less), one where the displacement of a small thing effects a greater change on the world than a revolutionary overturning of the old order and the remaking of all in a transcendent new image.

This is all to say that the Berman bridge — even when it is a guitar line or musical break and not a sung moment — delays. As he sings on "The Wild Kindness" before the exquisite final extended fade out of the guitar to the clock-like tick of the snare, it "holds the world to its word"; a "hold" that causes a suspension in time and forces a reflection on the ethics of our collective judgements. Importantly it is to its word — that human-to-human relational contract of speech — and not to the laws, which are so often the ruthless and mechanical enactment of an inhumane discipline to particular ends, that the world is held. Berman's aesthetic sought out a morality that emerged from within late capitalism and tried to reason the possibility of peace in the present without recourse to destruction, dissolution, or a transcendent outside of everyday time.

This sense of formal and lyrical delay is at the core of Berman's moral and aesthetic project. Berman's always-faltering delivery and stilted composition modeled a spiritual relationship to time that resisted the grinding rhythms of late capitalist exploitation. As the estranged son of notorious oil, tobacco, fast food and gun lobbyist Richard Berman, he was all too familiar with human and environmental demise. The subjects of many of his best songs live out their lives in spaces of exploitation and violence that emerge from late capitalist desires to suppress difference and delay in the pursuit of an order and control that is far worse than the alternative. The underdog protagonists of "Smith & Jones Forever," for example, wander a path of illegality in the "alleys" and "ghettos" of California, rejected and ignored by the wider populace, but when caught have a violence imposed upon them unequal to anything they committed in life. They are the neglected rejects of the new American West who are subjected to a condition of total vulnerability to the violence of the right-wing state as they face their "execution." Once again, it is in the bridge (not the chorus) that we find the song's ultimate statement on American brutality: "When they turn on the [electric] chair / Something's added to the air forever."

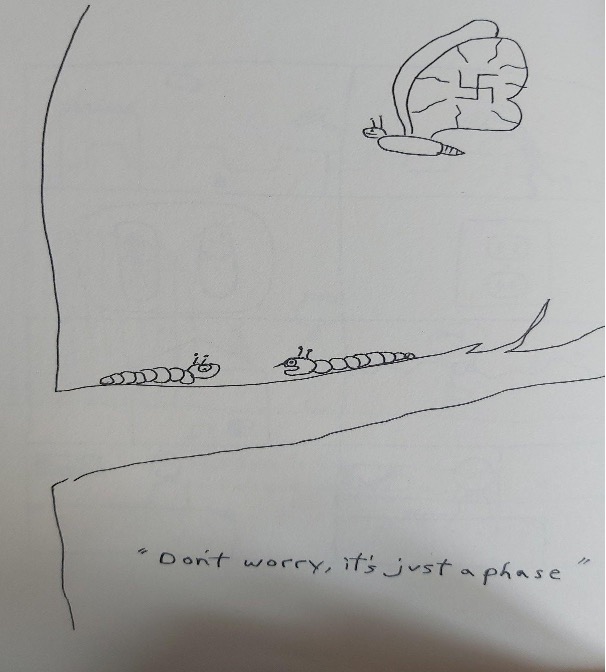

Time and violence occupied a common space in Berman's aesthetic universe. The rush to embrace a wholesale, radical change in a person or environment — the capitalist, and also modernist imperative for novelty — was often seen by him as an ethically-blind position for art and life to adopt in relation to the ongoing tragedy of the world. Berman's cartoons in The Portable February (2009) returned to the theme that the desire to transition unthinkingly to new stages of being contains within it the kernel of brutality, like a Futurist or fascistic death cult. One [fig. 2] depicts a butterfly that has emerged from a chrysalis with a swastika on its wings grinning as it heads to its reproductive future (and so too, one reasons, its end and the ends of others), while below it one seemingly harmless caterpillar quips to another, presumably blind to their own fate, "Don't worry, it's just a phase." The fascist butterfly barrelling toward a deadly futurity is a quintessential Berman image — one in which lightness, brightness, and joy belie a toxic complicity with the most extreme cruelties of twentieth-century history. But the cartoon also posits the ethical necessity of slowness. As Berman sang on "How Can I Love You If You Won't Lie Down," "Time is a game / Only children play well / How can I love you / If you won't lie down?" A sex joke, surely. But it's also a statement about the necessity of delay and repose to the work of love and care. It's a suggestion so common in Berman's work that modern life's relentless pace and dreams of rapid transition to a new place or state of being do not offer sufficient space for love.

As a response to late capitalist modernity, then, Berman's project avoided hippyish neo-Romantic demands for a return to a primitive state of being, and rock-accelerationist appeals to Nietzschean creative destruction. Instead, it embraced what he called in "The Wild Kindness" a condition of randomness and "lateness" where "forever [is] delayed," and in which we can learn to find a place of hospitality for the stranger, the vagabond, and the exile. As he sang so wonderfully in the Purple Mountains' "Snow is Falling in Manhattan," delaying the ordinary processes of time and commonsensical patterns of ritual and labor might open a door that invites in "an old friend [ . . . ] seeking shelter from the cold wind." Again, on "Time Will Break the World," Berman saw a focused, imagistic attention to the visual and poetic analogy ("the sky is low and gray like a Japanese table") as an enchantment of the world that depends upon a delay of our normative senses of relation. The environment of "Time Will Break the World" is an inhospitable one — a house where welcome is not to be found. Yet the abundance of the visual language and its strange conjunctions invites difference into this space of withheld hospitality, suspending time in order to generate possibility in a world frequently hostile to alterity.

Berman's songs suggest that the redemption of the present might lie in the truck stops, dive bars, and cheap hotel rooms — all bridges — that illuminate the late capitalist twilight of American grandeur and power, even as they index the tawdry and the maudlin. These sites of indistinction throw up forms of community that, however temporary, hold significance to those that experience them, and that may even help them to survive and hope just a little longer. Like the "Suffering Jukebox" blinking neon in the corner of a dead-end honky-tonk, Berman was a melancholic whose care for the world often ran the risk of misinterpretation by a self-centered society as being a dark inversion of their own base solipsism.

By making them carry the central message of his songs, Berman inverted classic rock form to make bridges sound like choruses and choruses sound like bridges. In "Send in the Clouds," in a moment that is technically a bridge, the rhythm guitar slows before the poignant question that sums up the track as a whole: "Why can't monsters get along with other monsters?" — a pained call to a perhaps-impossible community that leaves the following line, "Soi disantra" (so-called), to stand for a nonchalant and uncommitted answering chorus. "Federal Dust," too, instantiates its own sense of bathos (and absence of a chorus) when Berman and Stephen Malkmus sing "Here comes the coda" before a key change and lyrical shift to the slow, staccato, bridge-like mantra, "Not much water coming over the hill / Not much / Not much." If the bridge is the delay Berman needed to hold up the resolution of limitless difference into a final chorus, then the coda is the reopening of song form to that difference once again after a resolution; an all-important afterthought or amendment to the constitution that recognizes life as lived and not as a process of conforming to an earlier design. Berman's choruses rarely sounded convincingly like choruses, except on a few notable tracks like "Punks in the Beerlight" where the sunniness is really a false dawn laced with the delusions of alcohol and drugs. When Berman's wife Cassie joined the Silver Jews during the troubled production of 2001s Bright Flight, she seemed vocally to hold his hand and walk him through the chorus as though it were a dangerous place.

Berman's poetics of delay were not altogether tragic, though. Many of his songs were laugh out loud funny, often because of his relentless melancholy; they knew well that being stuck in the middle of something for too long can be as funny as it is frustrating. The entire genre of farce turns on this gimmick of mistiming and impediment: in "The Farmer's Hotel," for instance, the song's plot never quite arrives at its conclusion. Stuck in a podunk town, the narrator looks for a place of hospitality to stay overnight, only to find that detours mean he never finds it, and when he does it is a horror like nothing he imagined. The song denies the listener any semblance of chorus, instead giving them seemingly endless verses occasionally topped off with languid and warped guitar bridges. It is "Hotel California," if rather than being a place you could "check out any time" but "can never leave," it was one you could never quite find to begin with. Berman's humor was the humor of the person who wanted to hope for potential in the everyday American no-place, but recognised, too, that it was often precisely as bad as other people had suggested it might be.

The tragic irony of Berman's death, and what makes it so unbearable to all who loved him, was that in his last days he could delay no longer. Neither his urbane humor nor his sense of the spiritualized enchantment of the world were enough to withstand the pressures of everyday life. What hurts most is that if Berman's music taught us anything it was the potency and value of delay. To misquote that other great paradoxically misanthropic lover of humanity Samuel Beckett: delay again, delay better. For what is a life full of care, but one primed always to delay, after all?

Mike Collins (@dr_mjcollins) is Reader in American Studies at King's College, London. He is the author of the forthcoming Exoteric Modernisms: Progressive Era Realism and the Aesthetics of Everyday Life (EUP, Sept 2023) and The Drama of the American Short Story, 1800 - 1865 (Michigan, 2016). He is also the Editor (with Gavin Jones) of the forthcoming Cambridge Companion to the American Short Story (CUP, April 2023)

References

- Ernst Bloch in Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), 53.[⤒]