David Berman

In a long-lost Fader interview that resurfaced the day after David Berman's death, Nick Weidenfeld levels charges of solipsism and lack of empathy that he defines as "an inability to relate to the environment."1 While the accusation draws on Berman's own self-criticism, the suggestion that he is "someone who cannot comprehend a world outside of the self" seems both harsh and hard to maintain in the face of his work, teeming as it is with moments of recognition of the world and its inhabitants.2 In his poems and songs, Berman showed himself to be unusually attentive to the world around him, and to the phenomenon of attention itself. His words and worldview often suggest that self and world are inextricably linked in a reciprocally generative loop. In much of Berman's literary and musical work, boundaries between self and world are arbitrary and, at times, perilously permeable.

In space there is no center / We're always off to the side3

Berman claimed a peripheral place for himself in the world's attention ecosystem, suggesting in another 2005 interview that "I was not born to be the center of attention in a crowded room. I am trying to make my name as an acute observer, as a witness."4 This witnessing can be observed in his poems, in the songs he wrote with Silver Jews and Purple Mountains, in his cartoons, and even in his curation of links on his blog, Menthol Mountains; but attention, as he makes clear in these works, initiates chains of reciprocal processes that cannot always be escaped. The acute observer of the world becomes trapped inside the world he has acutely observed into being, left howling, like the speaker of "New Orleans": "Well, we're trapped inside the song / Where the nights are so long."5

These generative and fundamentally interpersonal properties of attention are central to the work of Swiss philosopher Yves Citton. Rather than viewing attention as a currency, the possession of individuals who own it and bestow it on their chosen recipients, he proposes that it is something we make in shared moments of "affective harmonization" with others.6 In Berman's poems, lyrics, and musical collaborations, Citton's central principles of "reciprocity, emotional connection and improvisation"7 enact themselves in practice in a flourishing attention ecosystem.

The poem "World: Series" shows these processes in action, describing and enacting a moment where the world, or a small slice of it, gets captured within the speaker's attention and becomes a poem before the reader's very eyes:

When something passes in the dark

I make a note on a pad kept by the window.8

The poem starts by charting the speaker's attention being drawn to the world outside his window, before flipping the relationship in the final stanza, which yields the point of view to a passer-by in the "outside" world:

When something passes in the dark,

I try to tell its side of the story.

"I am passing someone in the dark," it thinks . . . 9

Here, attention is shown to be inherently reciprocal, with subject and object bringing one another into being in a shared gesture.

Citton has noted that attention moves in a loop between distinct but entangled poles, but suggests that not enough attention is paid to the process by which something becomes meaningful enough to claim our focus:

The first movement of the loop is intuitive enough: we pay attention to something when it matters to us. What is less intuitive, but equally true, is the reverse movement: something starts to matter to us when we pay attention to it.10

As the presence of the wind can be seen in "the tension of the blown trees,"11 so the world, or at least a series of its "somethings," is captured in the frame of the speaker's focus. The moon is "illuminated by my attention,"12 and the ecosystem developing in Berman's poem flourishes in a stance of affective harmonization that allows the world's transient meanings to be "captured for a moment inside [the] work."13 The description of the window ("like looking out at the world / through the back of a teenage girl's head"14) opens the things of the world to the possibility of being seen from vantage points other than the speaker's own, a possibility reinforced in the conclusion's shift in perspective from the viewer at the window to the "something" passing by, a gesture that emphasises the reciprocity of attention between the things of the world and the self.

Sometimes I feel like I'm watching the world / and the world isn't watching me back15

Citton's book identifies a need for what he calls' "vaults," places built and sustained in joint attention rooted in care:

We are hopelessly in need of vaults [voûtes] where we can resonate and reason together: it is for us to protect and invent those which will help us to think and act better together, and be more present to ourselves as we harmonize better with the attention of others.16

Just such a resonant space forms the heart of American Water. In "We Are Real," attention is the mechanism through which self and world recognise each other's brokenness and reconstruct each other:

My ski vest has buttons like convenience store mirrors

And they help me see

That everything in this room right now is a part of me.17

An intricately-described object operates as a portal to an ecosystem built of intersubjectivities, in this case ski-vest buttons that allow the song's speaker to see that the self is always plural, built of things and people around him, reflected and presumably distorted.

In the album's closing song "The Wild Kindness,"18 the "I" that was "broken and smokin'" on the opener "Random Rules"19 has rebuilt itself to "shine out in the wild silence" of the world. Mirrors fail to offer recognition ("every leaf in a compact mirror/ hits a target that we can't see") and the portal offering intersubjective transformation takes the form of a "motel void." Shimmering moments of transcendence are opened within the song by Stephen Malkmus's guitar, described some 15 years later by Berman as "a long chain of sparkly notes, just going up and down, crowded and not crowded and sparse,"20 and the "delicate and generally spontaneous work of emotional harmonization"21 that Citton identifies as central to joint attention plays itself out in the words and notes of "The Wild Kindness." It cannot be gleaned from the lyrics in isolation. Rather, it emerges in the interplay between the lyrics in their cracked baritone, the plangent keyboard riff, and Malkmus's plaintive and raggedy backing vocals and chiming guitar line, in a dynamic of improvisational, intersubjective agency that operates like the "transindividual collective" that Citton describes as "pass[ing] through individuals, incorporating them into a reality that is larger than them: a system of resonance."22

Chris Stroffolino, a musician and poet who played keyboards and trumpet on American Water, has offered his own close reading of the song, identifying the lyrics' "Dickinsonian themes and settings" and outlining how its complex, looping timeline of past, present and future weaves itself in the interaction between musicians.23 Stroffolino notes that "Steve joins David on the chorus, as if this narrator is a 'we' more than an 'I,'" and this intersubjective narrator occupies a space-time that is fittingly multiple.24 The narrator's voice is woven through with the swirling keyboard in this opening verse. Moving into the bridge and the present, on the line "four dogs in the distance" the keyboards drop away, replaced by Malkmus's guitar, which lands on the words "distance" and "kindness," and his voice bolsters Berman's on the three iterations of the promise, "I'm going to shine out in the wild silence," before dropping away to let Berman intone "and spurn the sin of giving in" alone.

In the second verse, Malkmus's guitar chimes back in for "grass grows in the ice-box," and soundtracks a baffling time-skip where "it is autumn and my camouflage is dying" follows hot on the heels of "the year ends in the next room." Instead of a promise for the future, in the second chorus the two voices join on a prediction of the end of time: "Instead of time, there will be lateness." Berman's lone voice on the line "let forever be delayed" suggests resignation to the fact that all plans for shining out must be shelved in this late time-scape. Berman extends the word delayed by a full two syllables, and Malkmus's guitar rests for two beats, punctuated by two metronomic strums, before unfurling a guitar solo that is pure, ramshackle and sublime. Despite the frictions and tensions that beset their decades of on-off collaboration, Berman prized Malkmus as a guitar player who would "always serve the song."25 In an interview from around the time of American Water's release, Berman notes the affective harmonization central to Malkmus's improvisations with Silver Jews, observing that "when Stephen plays guitar on my songs, I feel like he's trying to play something more simple and tender. Basically, I think it's him trying to play what I would play if I were a good lead guitarist."26 Malkmus's attention, both to Berman's sensibility and to the needs of the song itself, pours forth in shimmering guitar notes that suture the rift between past and future — ensuring that, while forever may be delayed, the future has not been foreclosed. The solo serves to pull the song out of the suspended no-time imposed by the second chorus. In the final verse, time is reset to the past; the "motel void" and a meeting with the "coroner at Dreamgate frontier" hint that death may hover somewhere beyond the song's threshold.

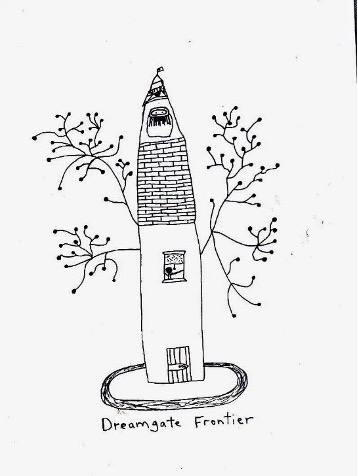

A cartoon (fig. 1) by Berman in the album's liner notes depicts Dreamgate Frontier as a hybrid rocket/tower/tree/neuron with a little man, arms open to embrace the world, looking out of its middle window. It's hard not to read this near-stickman as the song's "I," taking up a position at the window like that of the speaker of "World: Series" in order to capture something in his work's frame of attention, to "hold the world to its word."

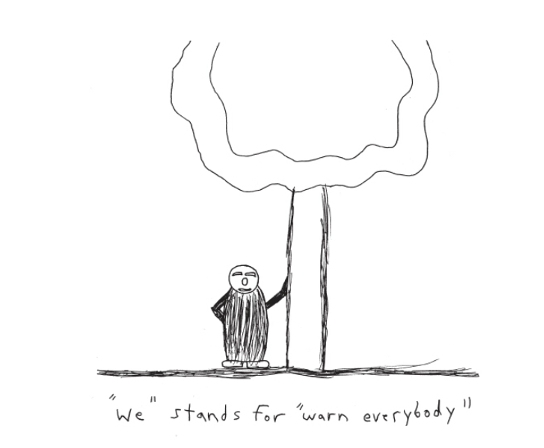

"We" stands for "warn everybody"

If refusing cloistered, hermetic selfhood offered a powerfully resonant space in the shared attention of "The Wild Kindness," it also risked leaving one vulnerable in the face of a toxic and overwhelming larger reality, teetering on the verge of a void. "We Could Be Looking for the Same Thing" proposes the interpersonal haven of a "we" as a refuge from the world, where "We could both spend happy lives / Inside the days of you and me."29 However, these songs remain alert to how fleeting and contingent this first person plural place of safety is. "What Is Not But Could Be If" stages the union of a "we" as the possibility of escape ("We could be crossing this abridged abyss / into beginning") from the grip of failure ("When failure's got you in its grasp / And you're reaching for your very last / It's just beginning").30 However, this beginning is proposed in a grammar that seems to place it beyond reach, couched in the conditional of "could be if" and accessible only via the precarious means of an "abridged abyss."

This vulnerability reveals a negative manifestation of Citton's "transindividual collective." A crippling susceptibility to the opinions of others functioned as the toxic corollary of the permeability that was Berman's access to genius, and the sense of a composite self that is too easily interpenetrated by words from the outside world suffuses his interviews.31 Those corollaries likewise nest amidst the chains of links to academic papers dealing with persona, self-perception, and response to the suffering of others that form the bulk of the last posts on Menthol Mountains.32 This agony of interpersonal embarrassment and fear of failure would prove intensely generative in his final years, offering an alternative glimpse of the "days of you and me" as if from the perspective of "passing someone in the dark."

The 2019 album Purple Mountains, by Berman's new band of the same name, took his burden of self-loathing, guilt and shame, and built a resonant space brought to life in the attention of its listeners. Themes of failure, bereavement and lost love fed into the polished, mordant, and, at times, excruciatingly revealing lyrics of Purple Mountains. On "That's Just the Way That I Feel" he wrote, "Course I've been humbled by the void / Much of my faith has been destroyed / I'm forced to watch my foes enjoy ceaseless feasts of schadenfreude," lines whose sound patterning is as sharp as the pain it describes.33 On "Darkness and Cold," contrast between his lost love's "pink champagne Corvette" and the "band-aid pink Chevette" where he sleeps "three feet above the street" offers a similar miracle of euphonically-expressed personal agony, reworked for the most public of consumption.34 While "People," on American Water, claimed that "Moments can be monuments to you / If your life is interesting and true," Purple Mountains pieces together an intricate mosaic of words from a shattered life.35 In the chorus of "That's Just the Way That I Feel," a perfectly weighted chain of syllables working through permutations of "stand" and "distance" marks the painful unravelling of a "we" into its constituting strangers:

And when I see her in the park

It barely merits a remark

How we stand the standard distance

Distant strangers stand apart.36

Moments that must have been incredibly painful to live and to write are presented to the listener in forms perfect enough to constitute monuments to a plural you. While many Silver Jews songs, from "New Orleans" to "We Could Be Looking For the Same Thing," center a first-person plural capacious enough to make room for the attentive listener, much of Purple Mountains feels like an attempt to pull this plural self apart, leaving its "portrait of a shattered man" bare in the glare of the listener's attention.37

After the increasing desperation of the opening three tracks peaks with "Darkness and Cold," however, "Snow is Falling in Manhattan" offers refuge and respite to the listener, an unexpected vault "where we can resonate."38 The song opens with a deft sketch of a New York snowstorm, a caretaker, and a friend taking shelter on his couch. In the second half, we're offered the antithesis of the threatening haunted house in "New Orleans" that trapped its singers in its song:

Songs build little rooms in time

And housed within the song's design

Is the ghost the host has left behind

To greet and sweep the guest inside

Stoke the fire and sing his lines.39

As in so many of Berman's songs, the listener finds themselves in a living house, this one haunted by a benevolent ghost left to welcome the attentive listener inside.40 The song builds the room, but it takes the listener's attention to populate the room and bring the song alive, "harmoniz[ing] with the attention of others."41

In a twist that has become almost impossibly moving in the time since Berman's death, the closing lines turn their attention on the listener:

Inside I've got a fire crackling

And on the couch, beneath an afghan

You're the old friend I just took in.

For all this album's attempts to cut an "I" loose from all the plural identities it used to inhabit, this song ends by suturing a "you" and "I" back together from the song's ghostly host and its listener. Berman's concern with the perspective of his listeners42 finds its purest form in this final gesture of attention, this song that makes a space for us to resonate along with his ghost long after he's gone.

Ellen Dillon (@altkrelb) is a poet and teacher from Limerick, Ireland. Her latest book, Fare Thee Well, Miss Carousel, is forthcoming from HVTN Press. Previous books look at Irish history from the perspective of butter (Butter Intervention, Veer 2, 2022), the teaching life of Stéphane Mallarmé (Morsel May Sleep, Sublunary Editions, 2021), and Stephen Malkmus's guitar (Sonnets to Malkmus, Sad Press, 2019). She teaches French and English at a rural secondary school.

References

- Nick Weidenfeld, "The FADER's 2005 Interview with David Berman," The Fader, August 8, 2019, https://www.thefader.com/2019/08/08/dying-in-the-al-gore-suite-the-fader-2005-interview-david-berman-silver-jews.[⤒]

- Weidenfeld, "Interview."[⤒]

- David Berman, "Ballad of Reverend War Character," track 4 on The Natural Bridge, Silver Jews, Drag City, 1996.[⤒]

- Ashford Tucker, "Silver Jews," Pitchfork, August 8, 2005. https://pitchfork.com/features/interview/6110-silver-jews/.[⤒]

- David Berman, "New Orleans," track 7 on Starlite Walker, Silver Jews, Drag City, 1994.[⤒]

- Yves Citton, The Ecology of Attention, (Cambridge: Polity, 2017), 86.[⤒]

- Citton, The Ecology of Attention, 110.[⤒]

- David Berman, "World: Series," Actual Air (Chicago: Drag City, 2019), 19-20.[⤒]

- Berman, "World: Series."[⤒]

- Yves Citton, "Fictional attachments and Literary Weavings in the Anthropocene," New Literary History 47, no. 2-3 (Spring - Summer 2016): 309-329.[⤒]

- Berman, "World: Series."[⤒]

- Berman, "World: Series."[⤒]

- Berman, "World: Series."[⤒]

- Berman, "World: Series."[⤒]

- David Berman and Stephen Malkmus, "Blue Arrangements," track 6 on American Water, Silver Jews, Drag City, 1998.[⤒]

- Citton, The Ecology of Attention, 105. [⤒]

- David Berman, "We Are Real," track 7 on American Water, Silver Jews, Drag City, 1998.[⤒]

- David Berman, "The Wild Kindness," track 12 on American Water, Silver Jews, Drag City, 1998.[⤒]

- David Berman, "Random Rules," track 1 on American Water, Silver Jews, Drag City, 1998.[⤒]

- Paula Crossfield, "David Berman - A Never Before Heard Interview from 2013 about the Making of American Water," August 8, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cqjwDK00rts.[⤒]

- Citton, The Ecology of Attention, 87.[⤒]

- Citton, The Ecology of Attention, 98.[⤒]

- Chris Stroffolino, "The Silver Jews' 'The Wild Kindness,'" Thing (blog), June 13, 2014. https://chrisstroffolino.blogspot.com/2014/06/the-silver-jews-wild-kindness.html.[⤒]

- Stroffolino, "The Silver Jews' 'The Wild Kindness.'"[⤒]

- Doug Wallen, "The Story of David Berman in 5 Songs," LNWY, August, 2019. https://lnwy.co/read/5-songs-david-berman/.[⤒]

- Unknown, "David Berman and Stephen Malkmus Interview," Cord Suit Silver Jews Archive, accessed December 17, 2022. https://tomsugden.github.io/cordsuit//articles/david-berman-and-stephen-malkmus-interview.html.[⤒]

- Stroffolino, "The Silver Jews' 'The Wild Kindness.'"[⤒]

- David Berman, The Portable February (Chicago: Drag City, 2009), 15.[⤒]

- David Berman, "We Could Be Looking For the Same Thing," track 10 on Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, Silver Jews, Drag City, 2008.[⤒]

- David Berman, "What Is Not But Could Be If," track 1 on Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, Silver Jews, Drag City, 2008. [⤒]

- See such interviews as Crossfield; Adalena Kavanagh, "An Interview with David Berman," The Believer, January 31 2020. https://culture.org/an-interview-with-david-berman/; Vish Khanna, "Kreative Kontrol Episode #481: David Berman," June 12, 2019, http://vishkhanna.com/2019/06/12/ep-481-david-berman/.[⤒]

- Links include articles on schadenfreude in children, persona and sense of self in clinic clowns, teasing in hierarchical and romantic relationships, counter-transference in interviews, and calculated overcommunication that share a concern with self-fashioning and self-positioning in relation to others and the wider world.[⤒]

- David Berman, "That's Just the Way That I Feel," track 1 on Purple Mountains, Purple Mountains, Drag City, 2019.[⤒]

- David Berman, "Darkness and Cold," track 3 on Purple Mountains, Purple Mountains, Drag City, 2019.[⤒]

- David Berman, "People," track 5 on American Water, Silver Jews, Drag City, 1998.[⤒]

- Berman, "That's Just the Way That I Feel."[⤒]

- Brian Howe, "Review: David Berman's 'Purple Mountains' Is a Welcome Return From an Old Master," Spin, July 16, 2019. https://www.spin.com/2019/07/purple-mountains-david-berman-review/.[⤒]

- Citton, The Ecology of Attention, 105.[⤒]

- David Berman, "Snow Is Falling in Manhattan," track 4 on Purple Mountains, Purple Mountains, Drag City, 2019.[⤒]

- Predecessors include the house in "New Orleans," the weeping house in "Time Will Break the World" (track 3 on Bright Flight, Silver Jews, Drag City, 2001) and the houses dreaming in blueprints in "Pretty Eyes" (track 10 on The Natural Bridge, Silver Jews, Drag City, 1996).[⤒]

- Citton, The Ecology of Attention, 105.[⤒]

- See, for example: "You have to be able to switch to the listener's point of view when you're preparing a song or writing it, switch back and forth like that John Travolta movie, Face/Off and be like: 'What objection might the listener have?'" (Grayson Currin, "Silver Jews," Pitchfork, August 18, 2008. https://pitchfork.com/features/interview/7519-silver-jews/.[⤒]