David Berman

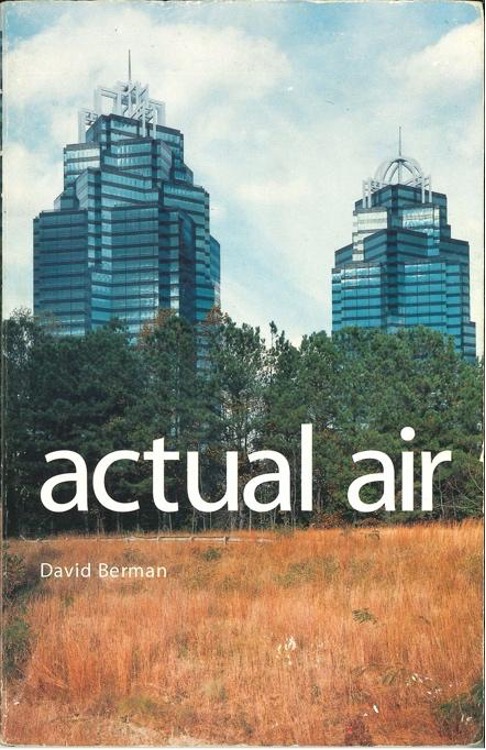

In Roe Ethridge's cover photograph for David Berman's book of poems Actual Air (1999), two glass office towers rise over a row of pines (fig. 1). Below, a dry and grassy wastage does a poor impression of amber waves of grain. Two monstrous buildings loom over this landscape, evocatively named Concourse Corporate Center V and Concourse Corporate Center VI by its developer, The Landmarks Group. Their equally humdrum nicknames, "King" and "Queen," refer to their postmodern chess piece parapets. Completed in 1991 in Perimeter Center, an area named for its location outside of the beltway encircling Atlanta, Georgia, these office towers anchor a 63-acre mixed-use real estate development. That same year, journalist Joel Garreau's Edge City: Life on the New Frontier described such large suburban business and entertainment districts, organized around freeway exits, as a portentous development in the reorganization of U.S. civic life.1 "Dear Lord, whom I love so much," prayed Berman's speaker in a poem near the end of the volume, "I don't think I can change anymore. // I have burned all my forces at the edge of the city."2

Actual Air, the first and most successful book published by Open City magazine's spin-off book imprint, sold more than 20,000 copies in the early 2000s, making it likely one of the best-selling poetry volumes of the era.3 Much of that success relied on a dawning consensus that an epigrammatic talent defined Berman's poems. In a 1999 review, musician Sean Nelson described Berman as a latter-day unacknowledged legislator writing quotable aphorisms "so sharp they'd be clichés if only the right people were in charge."4 If the enduring pleasure of Berman's aphorisms has never been in doubt, his feeling for Nelson's question about power has never had its due. Who really was in charge? What had destroyed the American landscape? Aligning literary reading with shaky remnants of municipal feeling, Berman saw civic space foreclosed by the edge cities he put on his book cover, expressing this dynamic in the obscure narrative conceits of poems such as "Governors on Sominex": "And out in the city, out in the wide readership, / his younger brother was kicking an ice bucket / in the woods behind the Marriott."5 Late in his life, Berman declared that he thought and wrote in "fragments" as a definite "product of a postmodern era," but postmodernism here might best be understood in its core sense of a spatial and architectural politics — the freeways and ex-farms that comprised its cordons sanitaire.6

To be sure, other talented lo-fi lyricists of Berman's cohort occasionally addressed themselves to this edge city. I think of Pavement's ludic corporate office park music video for "Gold Soundz" (1994), or of Scott Kannberg's first solo effort as Preston School of Industry, Goodbye to the Edge City (2001), its album cover advertising a stark border between a prairie and an herbicidal lawn. But the topical insistence of Berman's edge city autopsies distinguished his historical sense from these close associates. Some recent critics mistake this element in Berman's work for an idiom of place-based Americana,7 but his perception of American landscape was tuned in particular to its commercial declivities and sought to reappraise its psychic dynamics, structuring poems and songs from "Dallas" (1996) to "Margaritas at the Mall" (2019). In the decade before his 2019 suicide, he gathered a critical account of what he came to understand as neoliberalism in the hyperlinks and passages he logged at his cryptic blog mentholmountains: arc of a boulder, now connected explicitly to a conflict with his lobbyist father Rick Berman, and to a critique of historically specific practices of real estate speculation, corporate advertisement, and private enterprise's interference with public goods. But in the less programmatic explorations of the earlier poems, he offered fragmentary observations of getting along in a sprawled edge city world, "[c]ast as we are into this underimagined place."8 His fragmentary art of postmodern aphorism took the edge city's psychogeographical measures of spatial discontinuity, confronting a history with material coordinates in real estate development, privatization, and municipal nostalgia — and did so in part through what Andrew Epstein elsewhere in this cluster describes as aphorism's own proximity to "slogans, manipulative ads, and other instruments of degraded corporate language" that Berman loathed.

Office Parks and Spoiled Landscapes

Ethridge, now a distinguished commercial and fine arts photographer, captured his cover photo of Perimeter Center as a student artist. In the dawning age of megacenters, he reframed the deadpan stance toward spoiled landscapes that defined Bernd and Hilda Becher's industrial views or Robert Adams' pictures of sunbelt tract homes. Drawing a cold vision from German objective photography, Etheridge has described the buildings as "a kind of comic Cronenberg-y dystopic suburban future world. A lot of Atlanta was like that."9

Actual Air offers multi-perspectival accounts of moving toward, away, and through the edge city. In one poem, the poet drives "homeward," away from a perimeter "scattered like mushrooms about the beltway's exit ramp."10 Garreau called this specific typology a "Boomer":

Filled with cantilevers, ziggurats, soaring columns, and fields of glass, they are usually located at the intersection of the freeways, and are almost always centered on a mall . . . A Boomer is like poison ivy. If you have reason to wonder whether that's what you're in the middle of, chances are that's what it is. The classic tip-off: a car dealership being bulldozed to be replaced by an office building taller than the trees.11

The persona of the office park poem "The New Idea" gazes down from a building such as this: "From a third floor window I spray a sad look / down into the courtyard of the office park / filled with cold pebbles and benches." This speaker's confessional has to do with the misfit of human habitation to the alienated spaces of commercial feeling: a "dense history of uncomfortable moments" in haunted elevators, and other maladjustments of space and feeling: "that no one / ushered me as a blip onto this cold grid, // no one asked me to design my life to fit the dimensions of this situation." For the lyric speaker inside the high rises of Perimeter Center, the challenge of the poem is to retune human affects to corridors, conference rooms, and "mathematical mountains" of office walls.12 "The New Idea" thus evokes the speaker's alienation from the spaces and routines of managerial capitalism that had driven a postwar boom in suburban corporate office parks, and indeed his near total unfitness for enjoyment of the putative "pastoral" ideal of its well-manicured landscapes.13)

Berman's attention to postmodern architectural skylines, particularly the new popularity of contextualist glass windows, also developed across his own songcraft. In "Dallas" from the Silver Jews album The Natural Bridge (1996), he wrote of the town where he grew up after his father accepted a lobbyist position when he was seven:

O Dallas you shine with an evil light

How did you turn a billion steers

into buildings made of mirrors,

and why am I drawn to you tonight?14

Beyond its nod to the tune "Dallas" by Jimmie Dale Gilmore and The Flatlanders, I suspect this refrain alludes to the opening credits of the popular television drama Dallas (1978-1991), a primetime soap opera charting the Ewing family's oil dynasty exploits. The jagged title sequence offered a veritable edge city pedagogy, an up-tempo exercise in montaging, rezoning and tracking the transformations of oil derricks and cattle country into the system of modernized freeways and corporate office centers (fig. 2).

Berman seems to have seen the story repeat itself as Nashville began to boom during his residency there. "Suffering Jukebox" (2009) reworks the image as a relation of the metro developer to the logistics hub:

Planes on the downtown skyline is a sight to see for some

It ought to make a few reputations in the cult of number one

While these seconds turn these minutes into hours of the day

All these doubles drive the dollars and the light of day away.15

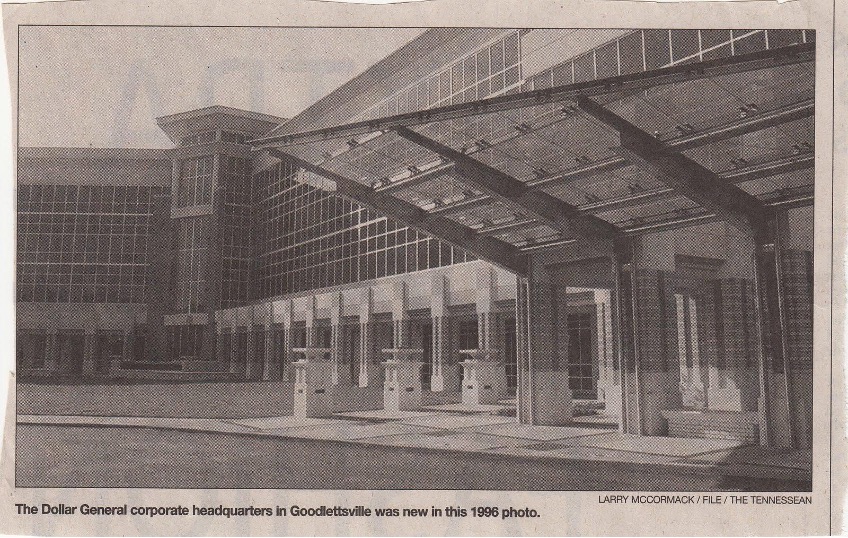

These stanzas of regional economic growth as concentrated poetic images of office parks and neoliberal metro development should be understood as constitutive motifs in a developing poetic system. He borrowed Mark Fisher's term "Capitalist Realism" for both commercial and residential typologies like these in a 2011 post on mentholmountains featuring clippings such as the Dollar General Corporate Headquarters in Goodlettsville, a boomer on the outskirts of Nashville (fig. 3).

The plundering of American landscape for commercial and residential development is one of the great themes of postwar architecture and landscape design, but this history is not often connected explicitly to the postwar poetry of landscape. I purchased Actual Air in summer 1999 before my senior year of high school. Around the same time, I first encountered the memorable admonition in Lew Welch's late 1950s "Chicago Poem":

All things considered, it's a gentle and undemanding

planet, even here. Far gentler

Here than any of a dozen other places. The trouble is

always and only with what we build on top of it.16

Welch made this observation about industrial blight in the postwar Great Lakes, but it named a larger phenomenon defined for his epoch by architectural critic Peter Blake's God's Junkyard: The Planned Deterioration of America's Landscape (1964). Blake's postmortem on the disfigurements of American commercial vernacular influenced such works as Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown's Learning from Las Vegas (1972), and the pursuant idioms of architectural postmodernism that connected the edge city's most ostentatious incarnations to the tawdriest strip mall typologies.

These lessons seemed perfectly extensive with the emergent geographies of the late twentieth century, where everywhere around us quarries, farms, brownfields and woodlands convulsed and strode forth as large, impetuously planned communities and zones of mass suburban speculation and development. Writing specifically of the Green Spring Valley of Baltimore County, the ecologist and landscape architect Ian McHarg had warned in the 1960s that "it was as if a new Homestead Act had been signed into law, as if every developer stood poised, his merchandise loaded on trucks . . . all alert for the pistol shot that would permit inchoate growth to spread its relentless smear . . . extinguishing the legacies of centuries of husbandry."17 The fresh clearing in the Green Spring Valley where my family purchased its quarter acre in 1994 was developed by Ryland Homes, a company that told an orthographic origin story about its brand name: "The name was created when Jim Ryan saw a sign that said 'Maryland.' The 'M' and the 'A' on the sign were concealed, and that combination of Ryan and Maryland created the perfect name for the new homebuilder."18 Architectural theories of postmodernism such as those of Venturi and Scott Brown hinged on these sorts of occlusive relations between commercial development and public wayfinding, as in Scott Brown's image of Las Vegas Strip neon crowding out "No Parking," "Speed Limit," and "Turn Only" signage (fig. 4). Berman offered a similar bit of apocrypha about the band name "The Silver Jews." As he put it to reporter Wyatt Mason: "When I was working at the Whitney I stared out the window and a sign said 'Silver Jewelry' but from my angle you couldn't see the end."19 Berman often sought poetic transformation in the everyday discursive operations of the commercial vernacular, as in a 2014 mentholmountains post singling out strip mall store names (fig. 5).

Feeling for commercial deformations of language and landscape entailed an attention to the psychic effects of advertisement. In "Self-Portrait at 28" he wrote of "the ideal of Virginia / brochured with goldenrod and loblolly," making a verb of the glossy brochure as the very mediator of nature description. He imaginatively identified with airport-adjacent homeowners whose noise complaints he frequently encountered in newspapers, but expressed befuddlement at the advertisements shaping his empathetic identifications with them:

I am in bed late at night

in my house near the airport

listening to the jets fly overhead,

a strange wife sleeping beside me.

In my mind the bedroom is an amalgamation

of various cold medicine commercial sets.20

Frequently, the interposition of advertising derailed his very faith in the operations of language and perception:

I can't trust the accuracy of my own memories,

many of them having blended with sentimental

telephone and margarine commercials,

plainly ruined by Madison Avenue,

though no one seems to call the advertising world

"Madison Avenue" anymore. Have they moved?21

Poems and songs therefore became arenas of reversal and resignification, where the detritus of spoiled landscape could be reimagined in the space of art. His explanation for the album title "The Natural Bridge" follows a related operation of commodified landscape description:

"I was in the [Natural Bridge Park] gift shop and realized if I called the album Natural Bridge, everything in the store would instantly be converted into promotional merchandise."22 If the process that reduced the auratic landscape to kitsch had long been complete, Berman now imagined the indie rock album as a promotional mechanism that could swallow and reabsorb the kitsch display in turn.

Privatization and Municipal Nostalgia

The edge city's transformations of landscapes went hand in hand with its hollowing out of municipal governance, a theme that arrested David Berman's attention perhaps as much as any other. Garreau's account of the edge city dubbed one of its distinctive features "shadow governments," which came in forms such as draconian homeowner's associations, "quasi-public institutions" such as reclamation districts, and public-private partnerships. These structures acted like governments — they created regulatory regimes, assessed fees, and even exercised coercion that looked like police power — while dispensing with the trappings of electoral accountability.23

Berman peoples the poems of Actual Air with the ghosts and remnants of a self-governing polity, hollowed out at every turn. In "The Charm of 5:30," a paean to the unlikely prospect of civic joy (where "random 'okay's ring through the backyards") transforms into an occult meditation on a religion of the state. Half-heartedly protesting the very public square that safeguards his speech, an ambivalent figure of neoliberalization triggers the poem's shift: "There's a shy looking fellow on the courthouse steps, holding up a placard that says 'But I kinda liked Reagan.'" In a turn fit for a Baudelairean flaneur, this Reaganite sees a beautiful passerby who Berman subsequently imagines spending her evenings playing 78s "beside her homemade altar to James Madison," a deep image of state fidelity erupting in the depths of ordinary evening routines. For Berman these legislative convictions often have primordial relations to American landscape, which vanquish the fleeting figures of neoliberal anomie. As he declares in the same poem: "It occurs to me that the laws are in the regions and the regions are in the laws, and it feels good to say this, something that I'm almost sure is true."24 Here again the celebration of "place" in Berman's work ought to be distinguished from the geography of national fantasy, relating more particularly to a vindication of municipal and civic processes.

Although the perfect day of civic possibility described in "The Charm of 5:30" is one in which "you won't overhear anyone using the words 'dramaturgy' or 'state inspection,'"25 Berman's poems and songs teem with the semantics of "state inspection." He everywhere peoples his stanzas with governors, bureaus, committees, judges and juries, homeowners, and highway commissioners. Berman inserts these mechanical archetypes of civic life where they do not belong, silver ribs amidst drippy nostalgia, search party conceits, and storylines of loss and decline. He presents himself as a bard of municipal vision in a neoliberal era. "When the governor's heart fails / The state bird falls from its branch," he writes in "Pretty Eyes" (1996). "Federal woman needs municipal man," he declares in "People" (1998).26

Tawdry private enterprises often perform the gutting of this municipal vision. In "Classic Water," one such tone-setting verse interrupts a nostalgic reverie:

At volleyball games her parents sat in the bleachers

like ambassadors from Indiana in all their Midwestern schmaltz.

She was destroyed when they were busted for operating

a private judicial system within U.S. borders.27

Variations on the motif emerge frequently: in a prose poem of rock music practiced in a region of economic decline, the whole atmosphere takes on the quality of the privatized toll road: "This place is like a haunted turnpike."28 In "Community College in the Rain," a large chorus of "Dougs," describing themselves as "injured by golf cleats," declare their unavailability for the institutions of public life.29 A harsh semantics of privatization (busting, piking, cleating) impels the public toward vectors of decline (falling from the branch, haunted, in the rain).

Berman often goes further than decline, linking electoral politics and civic processes to autopsies and murders: "She wore a dress of voting booth curtains / to a party at the coroner's split-level ranch," begins the poem "Coral Gables."30 Another, "Democratic Vistas," allusively replaces the old Walt Whitman vantage point with the University of Texas at Austin clock tower where Charles Whitman went on a 1966 killing spree. In "Civics," the poet joins a search party for a missing court stenographer. In other moments, civil society is simply asleep on duty, as in the poem titles "Governors on Sominex" and "From His Bed in the Capital City." Elsewhere, in "Coral Gables," foreclosure of public goods takes the shape of unrequited love: "She left the party at midnight, on the arm of a man /who had carved a government agency's initials / into a tree as a teenager."31 In still another song, "How to Rent a Room" (1996), the singer implores his lover and his listeners to discover his own death by reading the newspaper metro section. Again and again, the poems and songs cite pressure on the diction of public goods, civic processes, and municipal feeling.

As is well known, Berman followed the 2009 breakup of the Silver Jews with a public declaration of estrangement from his corporate lobbyist father. He rented a room near Dupont Circle and for a time endeavored to write a book critiquing Rick Berman.32 The book never materialized, but in 2011 mentholmountains began to reconstitute the underlying forms of programmatic study. It can be understood as a commonplace book of his wide readings. There are posts on poetry, music, Jewish teachings, and ephemeral curiosities, but throughout he maintained consistent threads on public policy, corporate history, political theory, and in particular the critique of neoliberalism. In one of his last extended interviews he synthesized these readings:

I came across the same obstacles over and over again, which are basically the United States Chamber of Commerce and business organizations — National Association of Manufacturers — and the history of corporate propaganda and its subverting democracy.33

Berman did not shy away from locating this "history of corporate propaganda" within a Republican political program that he linked to intensely personal experiences of history:

It is pretty much my father's work that I think in a way revolutionized Republican politics and made it far more aggressive and I've never been able to separate my upbringing from what I see on TV.34

These elements of Oedipal drama tend to blunt Berman's efforts to construct an encompassing critique, but it is worth retracing his bibliography in the years after the recession. His eye for detail led him to spotlight papers entitled "Wal-Mart: The Panopticon of Time,"35 Joan Didion's analysis of Newt Gingrich's use of lists as a sign of his management aesthetics, and footage of students at the Stockholm School of Economics that dubbed themselves the Milton Friedman Choir and produced a hymnal from the text of Capitalism and Freedom.

He was particularly keen to read histories of corporate propaganda such as Deadly Spin (2011), Wendell Potter's insider expose of corporate PR in the insurance industry,and Silver Bullets (1993), Richard Burgess'saccount of the conservative Coors beer dynasty. In the same moment, he absorbed critiques of neoliberalism by Jodi Dean, Wendy Brown, Jason Read, David Graeber, and others. He keyed to Dean and Brown for their accounts of commercial mechanisms of depoliticization. As Brown wrote:

This conversion of socially, economically, and politically produced problems into consumer items depoliticizes what has been historically produced, and it especially depoliticizes capitalism itself. Moreover, as neoliberal political rationality devolves both political problems and solutions from public to private, it further dissipates political or public life: the project of navigating the social becomes entirely one of discerning, affording, and procuring a personal solution to every socially produced problem.36

Although Berman sought to narrate this post-recession political turn in his own thinking as a flight from his poetry and song, it evidently carried forward the core preoccupations that had long structured his poems — the fragmentary and epigrammatic attentions to landscapes spoiled by the geographies of privatization and development, and a conjury of lost municipal feeling in its interstices. Rather than read mentholmountains as the cryptic, fragmentary liner notes to a political synthesis beyond his reach, or as the extension of the obscurantism that defined an early indie rock market orientation, it might guide us back to a latent politics in Actual Air, retuning our enduring interest to the poetry's keen historical feeling for the decline of public goods, the "cold grid" where we still are.

Harris Feinsod (@feinsod) is Associate Professor of English and Comparative Literary Studies at Northwestern University. He is the author of The Poetry of the Americas: From Good Neighbors to Countercultures (Oxford, 2017) and the co-translator (with Rachel Galvin) of Oliverio Girondo's Decals: Complete Early Poems (Open Letter, 2018). Recent essays appear in Comparative Literature, The Baffler, In These Times, and Central American Literatures as World Literature (Bloomsbury). He is currently writing a book about modernism and the sea.

References

- Garreau's national survey of Edge Cities included a spotlight on one family living in Perimeter Center, the African American husband and wife George and Patricia Lottier, who ran a novelty cup business called "Plastic Impressions" and a monthly magazine focusing on the affluent business community called The Atlanta Tribune. Joel Garreau, Edge City: Life on the New Frontier (New York: Anchor Books, 1991), 144.[⤒]

- David Berman, Actual Air (New York: Open City, 1999), 90.[⤒]

- Wyatt Mason, "So You Want to Be a Poet, I Mean Rock Star, I Mean Poet," New York Times, October 19, 2005. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/10/19/arts/music/so-you-want-to-be-a-poet-i-mean-rock-star-i-mean-poet.html. [⤒]

- Sean Nelson, "Book Review: Actual Air," The Stranger, August 26, 1999. https://www.thestranger.com/books/1999/08/26/1855/book-review-revue. [⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 9.[⤒]

- Vish Khanna and David Berman, "Episode 481: David Berman," Kreative Kontrol with Vish Khanna (podcast), June 12, 2019. http://vishkhanna.com/2019/06/12/ep-481-david-berman/. [⤒]

- For example: Spencer Kornhaber, "David Berman Saw the Source of American Sadness," The Atlantic, August 13, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/08/david-berman-silver-jews-american-lyrics/595969/ [⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 73.[⤒]

- Roe Ethridge (@roeethridge). "In 1998, maybe six months after moving to NYC from Atlanta, I had the wild good fortune to become friends with David Berman [. . .]". Instagram, August 7, 2019. https://www.instagram.com/p/B041nrPhlEN/. [⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 83.[⤒]

- Garreau, Edge City,115.[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 71-72.[⤒]

- See Louise A. Mozingo, Pastoral Capitalism: A History of Suburban Corporate Landscapes (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "Dallas," track 6 on The Natural Bridge, Drag City DC101, 1996, compact disc.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "Suffering Jukebox," track 3 on Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea,Drag City DC 358, 2008, compact disc. [⤒]

- Lew Welch, Ring of Bone: Collected Poems of Lew Welch (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2012), 25.[⤒]

- Ian McHarg, Design with Nature (Garden City, New York: The Natural History Press, 1969), 79.[⤒]

- Ryland 2002 Annual Report (Ryland Group, 2002): 24-25. https://www.annualreports.com/HostedData/AnnualReportArchive/r/NYSE_RYL_2002.pdf. [⤒]

- Wyatt Mason, "So You Want to Be a Poet."[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 58[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 60.[⤒]

- Ryan H. Walsh, "The Untold Story of Silver Jews' The Natural Bridge: How David Berman Lost His Mind, Left Pavement Behind, And Made A Masterpiece," Stereogum, October 3, 2016. https://www.stereogum.com/1902185/the-untold-story-of-silver-jews-the-natural-bridge-how-david-berman-lost-his-mind-left-pavement-behind-and-made-a-masterpiece/reviews/the-anniversary/. [⤒]

- Garreau, Edge City,187.[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 24-25.[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 24.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "People," track 1 on American Water, Drag City DC 149, 1998, compact disc[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 4.[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 52.[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 23.[⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 69. [⤒]

- Berman, Actual Air, 70[⤒]

- David Malitz, "David Berman was the cult musician who went away for 10 years. What made him finally come back?" The Washington Post, June 13, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/style/david-berman-was-the-cult-musician-who-went-away-for-10-years-what-made-him-finally-come-back/2019/06/03/19735620-77db-11e9-b7ae-390de4259661_story.html. [⤒]

- Khanna and Berman, "Episode #481."[⤒]

- Khanna and Berman, "Episode #481." [⤒]

- Max Haiven and Scott Stoneman, "Wal-Mart: The Panopticon of Time," Working Paper Series, Institute on Globalization and the Human Condition, McMaster University, April 2009. https://ciaotest.cc.columbia.edu/wps/ighc/0017040/f_0017040_14577.pdf. [⤒]

- Wendy Brown, "American Nightmare: Neoliberalism, Neoconservatism, and De-Democratization," Political Theory 34, no. 6 (December 2006): 704. Quoted in David Berman, "Ladie's Night," mentholmountains: arc of a boulder, March 24, 2012. http://mentholmountains.blogspot.com/2012/03/depoliticization.html. [⤒]