David Berman

In "Snow," the opening poem of David Berman's first and only collection Actual Air, the speaker walks through a winter scene with his younger brother:

I pointed to a place where kids had made angels in the snow.

For some reason, I told him that a troop of angels

had been shot and dissolved when they hit the ground.

He asked who had shot them and I said a farmer.

His brother asks why they were shot, and the speaker improvises that "they were on [the farmer's] property". "When it's snowing", he continues, "the outdoors seem like a room".1 "Snow" constructs a familiar world in Berman's writing; America as a desacralised zone, one in which transcendent bodies meet the immovable force of ownership, and where angels can be dissolved in the name of property. The spaces left by those heavenly bodies can be perceived now only through the edges of the landscape that they touched, a rough shape made by an evaporating body in a substance — snow — that will itself disappear. We assume, too, from the speaker's recollection, that the shapes of the angels are now long gone, remembered only in these lines. The brute fact of property is set here against the memorialising mind, which carries, in defiance, the idea of the landscape's arrangement as a "room," a remembered place in time.

Berman lived and wrote within an era characterised, to use Fredric Jameson's famous term, by the cultural logic of late capitalism. His poems and lyrics are preoccupied with how this logic deforms American culture at the same time as being an inherent part of it. For Berman there is no contemporary urban American landscape, to adapt Walter Benjamin, that isn't also somehow a document of barbarism, a record of the eradicative echo of American colonialism and capitalism. Berman's response to this is to twist that logic yet further; to take it to absurd conclusions ("What if it cost 25c to wake up in the morning? / A dollar, ten dollars?"),2 to grant objects sentience ("All houses dream in blueprints"),3 to collapse timeframes together ("I broke in one-hundred years ago / With a dagger tucked in my vest"),4 or to configure historical progress as possessed of a kind of evil magic ("How'd you turn a billion steers / Into buildings made of mirrors?").5 After Berman split Silver Jews in 2009, it became clear that these evocations of the compromised landscape had a deeply personal dimension; he revealed in an essay, titled "My Father, The Attack Dog," that he was the son of the right-wing lobbyist Richard Berman, and that the mission of Silver Jews had been to operate as an opposing force to the damage done to America by the man he called "a world historical motherfucking son of a bitch."6 On this view, his creation of "rooms" in time takes on the characteristics of a counterforce, one determined to remake this degraded landscape. "Moments can be monuments to you / If your life is interesting and true" he sings, an early mission statement, on American Water's "People."7

The poem "Classic Water" is one of Berman's fullest evocations of this process. Its timeframe is flattened, simultaneous; the speaker and his friend Kitty wash a stagecoach, but also drive a car and listen to shortwave radio. Like "Snow," the poem takes place against a backdrop of zones compromised by capital or regulation; Kitty's parents are "busted for operating / a private judicial system within U.S. borders," and their leisure time is spent by "the government lake." Elsewhere, the speaker recalls how they once got so high they "convinced [them]selves / that the road was a hologram projected by the headlight beams." If, then, the horizon of the unspooling road is foreshortened and compromised, one must instead look inward and conjure a world: a memory, a room of the kind the speaker creates in "Snow." Within this depthless world, the refuge in "Classic Water" comes from the speaker and Kitty imbuing each other with the depth absent elsewhere, and forming a space there in which to dwell: "I remember the night we camped out / and I heard her whisper / 'think of me as a place.'"8 By seeing America as a bricolage of rooms in time, places built dialogically between people, one might begin to unpick the nation's totalising, flattening logic.

*

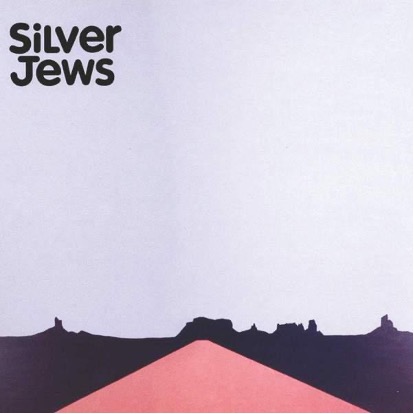

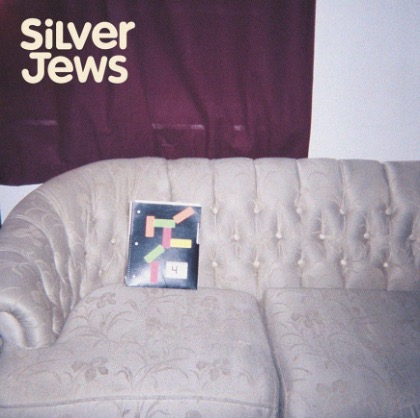

This logic extends to Berman's use of images in his work. Tal Rosenberg notes that the covers of Silver Jews albums all feature versions of horizons:

Whether literal (a desert road for American Water [fig. 1]) or symbolic (2001's Bright Flight [fig. 2], where your drug-induced horizon doesn't go further than your living room couch), I always took the visual signifier to mean that, no matter where you are, there's always something beyond you — either physically, personally, or creatively.9

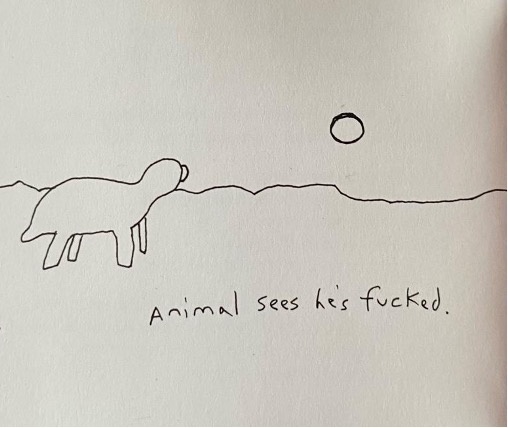

Rosenberg sees this expression of the world beyond the self as a challenge to the ego, but there's another dimension to these horizons; like the world Berman describes, they're artificially generated, simulated, fucked-with. The cover of American Water is itself a parody of the classic desert landscape from the American Western. Its sense of perspective is foreshortened by a flat collage that destroys the image's vanishing point, not unlike the stoned mirage of the headlight beams' hologram from "Classic Water." It's a simulation of distance, a road you can see but not ride. This flatness is mirrored in Berman's collage designs for the album inner-sleeves, where cut-out pictures from lifestyle magazines are juxtaposed with photographs of civil war memorials and Berman's own cartoons. This deliberately absurd stew of patriotic images, much like the frequent temporal slippage between eras of American history in Berman's lyrics, satirically illustrate a nation calcifying in its own depthlessness. In one cartoon in the inner sleeve of American Water, a four-legged creature looks at the sun falling behind a flatly sketched horizon, a pithy caption below: "Animal sees he's fucked" (fig. 3).

To imagine a room to which one can retreat in the face of this depthlessness implies a kind of temporary escape. In "Classic Water," this is a place shared between two people who instil in each other the characteristics of the lost landscape in which they live. However, this retreat can also be configured as a self-imposed exile, a place apart from which vantage one can see the world's operations alone. On "The Wild Kindness," the final track on American Water, Berman sings "I'm gonna shine out in the wild silence . . . and hold the world to its word."10 We might, then, understand his decade away from public view, from the disbanding of Silver Jews in 2009 to his return with Purple Mountains in 2019, as another of his works; a wild, silent one that is nevertheless preoccupied with holding this world to account. Berman's withdrawal seems to speak simultaneously to a desire to remove oneself from any structure that might colonise or compromise one's art, and to make that non-compliance into its own artistic statement.

Returning from a long period of wild silence carries its own peculiar difficulties. Berman's 2019 comeback and final statement, the album Purple Mountains, suggested that he had regained a sense of how his work might respond to a zone of American politics and economics substantially more debased than when he left it. The era of the 45th president played out like something from the darker reaches of a Silver Jews song; a political and environmental catastrophe of simulation, television and celebrity. "I have no idea what drives you mister," Berman sings in "Time Will Break The World," a lyric that could, of course, refer to Berman's father, but could also be easily applied to the actions of the former president. In the same song, Berman laments: "It's so very cold in the mansion after sunset / The snow is blowing through the baseboard outlets."11 In this, another snowy image, the sun sets on the dilapidated house of the American century, its insolvency indicated by its permeability; the snow encroaches, freezing the world further into stasis. But the snow itself, as Berman has said, can make a room, and perhaps that porousness between the inside and outside illustrates the importance of contingency; one cannot live in total exile, and one cannot always set the terms of one's occupation. When Berman returned, the room had changed.

*

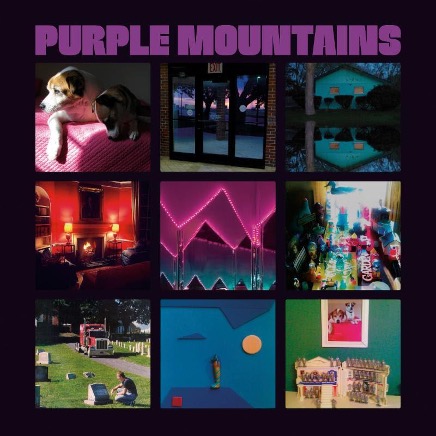

The cover of Purple Mountains features nine pictures in a 3x3 grid (fig. 4). At top left is an image of two dogs, and at bottom right a photograph of the same dogs hangs on the wall above a toy house.

The former is a picture from a domestic place; the latter suggests an enclosure of and distance from that world: a horizon lost, shrunk and made into an object. It appears to have been taken in another room, the apartment above Drag City's offices in Chicago where Berman lived during the last months of his life following the end of his marriage. He filled this room, according to reporter John Lingan, with "dollar-store junk."12 Berman, however, was no anchorite, and his final months were spent in a blizzard of communication with fellow musicians, journalists, and fans. In an interview with Loud and Quiet, Berman identified "hospitality" as a key function of the songs on Purple Mountains, a theme that is clearly a development of the rooms or places in his earlier poems and lyrics. In a response that recalls the sacral forms of the angels in "Snow," Berman considers, in a crystallisation of some of those earlier poetic ideas, that a song itself might also become a place:

Slowly I started to realise . . . how a song could be a place that you resurrect every time you play it . . . There was a Silver Jews song called "There Is A Place." One of the things in Judaism is the name for God — it's the omnipresence, or "The Place."13

Hospitality has a long history in Berman's writing — "Introduction II," the opening song on the first full Silver Jews album Starlite Walker, begins "Hello my friends / Come in, have a seat" — but on Purple Mountains this obtains a new urgency and clarity.14 Property, that cursed thing that destroys the angels in "Snow," is defied in the songs of Purple Mountains by a temporary collective spell, a new place that tries to stand, ghostly, outside the boundaries of private ownership. This is exemplified most clearly in the beautiful "Snow is Falling in Manhattan," in which Berman describes a refuge from a New York snowstorm where "on the couch, beneath an afghan / lies an old friend he just took in." From inside this temporary house, he sings:

Songs build little rooms in time

And housed within the song's design

Is the ghost the host has left behind

To greet and sweep the guest inside

Stoke the fire and sing his lines.15

In the desacralised world, to borrow the title of one of the earliest Silver Jews songs, "You Can't Trust It to Remain," but these works, immaterial rooms in time, nonetheless provide listeners with a form of temporary shelter.16 Here, the little room created by the song keeps the snow out; the consolidation of the idea of the room in time has moved from a room made of snow ("Snow") to a porous house into which snow is blown ("Time Will Break the World") to a warm, sheltered space surrounded by snow, the song forever occupied by a ghostly iteration of the songwriter who is inextricable from the place they have created. Like Kitty in "Classic Water," we should think of them both within and as the place itself. The maturity of Berman's songwriting here affords a confidence in his position as author and host; he can now build rooms and refuges for others to inhabit, even when he is absent. It's poignant that this philosophy survives Berman's passing; he built rooms in time, occupied by his voice, which the listener is always free to revisit.

*

A few weeks before Berman died, I was contacted by a representative from Drag City to set up an interview during the proposed Purple Mountains UK tour in Spring 2020. The representative said that David was really keen to talk; I think about this often. I spoke to David in person only once, at a Silver Jews gig in 2006 where we talked about some correspondence that we'd had the previous year. It was obvious at those concerts that he drew immensely from the love the crowd felt for him, and to see those songs enacted live was one of the great privileges of my life. To write those songs, to perform them in a little room in time, to create that refuge despite everything else; that counts for something.

David Hering (@hering_david) is Senior Lecturer in English at the University of Liverpool. His writing has appeared in Guernica, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The London Magazine, 3:AM, The Quietus, and others. He is author of David Foster Wallace: Fiction and Form (Bloomsbury, 2016). In 2019 he was shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize and in 2020 the Northern Book Prize. He is currently working on two novels and a short story collection, as well as a scholarly book on a new theory of haunting in contemporary culture.

References

- "Snow," Actual Air (New York: Open City, 1999), 5.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "The Country Diary of a Subway Conductor," track 8 on Starlite Walker, Drag City DC55, 1994, compact disc.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "Pretty Eyes," track 10 on The Natural Bridge, Drag City DC101, 1996, compact disc. [⤒]

- Silver Jews, "New Orleans," track 7 on Starlite Walker.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "Dallas," track 6 on The Natural Bridge.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "My Father, The Attack Dog," menthol mountains, January 22, 2009.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "People," track 5 on American Water, Drag City DC149, 1998, compact disc.[⤒]

- "Classic Water," Actual Air, 6.[⤒]

- Tal Rosenberg, "Remembering David Berman, Poet Laureate of the Void," Fader, August 8, 2019.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "The Wild Kindness," track 12 on American Water.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "Time Will Break the World," track 3 on Bright Flight, Drag City DC215, 2001, compact disc.[⤒]

- John Lingan, "David Berman Returns," The Ringer, July 10, 2019.[⤒]

- Jenkins, Dafydd, "Purple Mountains - The Eventual Return of Silver Jews' David Berman," Loud and Quiet, August 6, 2019.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "Introduction II," track 1, Starlite Walker.[⤒]

- Purple Mountains, "Snow is Falling in Manhattan," track 4 on Purple Mountains, Drag City DC680, 2019, compact disc.[⤒]

- Silver Jews, "You Can't Trust it to Remain," track 6 on The Arizona Record, Drag City DC28, 1993, compact disc.[⤒]