Reading with Algorithms

If you've walked into your local Barnes & Noble bookstore recently, you likely encountered a table of BookTok books like the one pictured in Figure 1. Part book club, part fan community, and part social media trend, BookTok has received significant media attention in recent years as a force for good in the publishing world. Since 2020, books popular on BookTok have launched the careers of new writers, found new, expanded audiences for formerly midlist authors, and have been credited, in some media outlets, with re-popularizing the printed book. As of January 2023, videos tagged with "#BookTok" on TikTok have over 100 billion views, and Barnes & Noble's BookTok table capitalizes on this popularity. In a large room of mostly dark wood and forest green, the table stands out, covered in stacks of books with bold covers and striking fonts that often include an illustration of the main characters or a figure or object emblematic of the author's brand. The titles include recent releases from some of the most popular and bestselling "BookTok authors," as well as titles currently trending on BookTok, many of which are romance novels, or as BookTokkers often refer to them, rom-coms. The latest Colleen Hoover releases? Some "fairy porn," as it's often referred to on BookTok (Sarah J. Maas's A Court of Thorns and Roses series)? Some Tessa Bailey, Emily Henry, or Ali Hazelwood? They're all there. Readers can also find these titles and more by browsing the "BookTok" category on Barnes & Noble's website.1

While BookTok has contributed to the recent rehabilitation of Barnes & Noble as the (anti-Amazon) hero of readers everywhere, the publishing industry has also taken notice. In September 2022, Penguin Random House announced a partnership with TikTok that allows creators to link directly to books in their videos, automatically creating playlists featuring other videos about specific books that interested users can explore. As of September 2022, Penguin Random House had spent $1.4 million on TikTok, more than any of the other Big Five publishing houses. This total is about 16% of the $8.76 million they spent on digital advertising of any kind in 2022 from January to September.2 Clearly, Penguin Random House is aiming to replicate for its own authors the runaway success enjoyed by some on the platform. Perhaps no author is more associated with this kind of BookTok success than Colleen Hoover, author or co-author, as of this writing, of nearly 30 emotionally intense romance novels. While Hoover — CoHo to her fans — was a bestselling author and savvy promoter of her work on social media before BookTok, her popularity on the platform has led to major mainstream success.3 According to NPD Bookscan, Hoover wrote 6 of the top 10 bestselling books of 2022.4

Yet, despite the involvement of industry players, on BookTok, readers control the conversation. Most accounts and creators who post BookTok content are readers, not bookstores, publishers, or authors. And these readers want to talk with each other about the books they are reading. It may not last: TikTok is currently banned in several countries and cannot be used on federally- and many state-owned devices in the United States. Yet for the moment, for those who can access it, BookTok provides a glimpse of what readers today are talking about when they talk about books.

The media sensation BookTok has provided — its popularity with users and creators, and the promise it seems to hold out to publishers and booksellers — relies on its ability to recast the conventional form of the literary recommendation. BookTok emerges at the intersection of two regimes of recommendation: one, far older than social media, relies on cultural authority and personal taste; the other, which has come to define twenty-first-century consumption, is driven by algorithmic systems. From reviews in the New York Review of Books and long-form pieces in the New Yorker, to the Book of the Month Club (heavily advertised, at least to me, on BookTok), to college syllabi and fanzines and Tumblr posts, the act of recommendation links criticism, fandom, and scholarship. As speech acts, recommendations carry a normative force that has long relied on the cultural authority of recommenders — figures whose credibility authorizes a recommendation's sense of prescription, attempt at persuasion, or even, sometimes, compulsion. The contemporary omnipresence of algorithmic recommendation systems such as TikTok, however, challenges these practices of recommendation, as these systems offer recommendations about what to read or watch next based on a consumer's past purchasing or viewing history.5 Rather than the cultural authority of either critic or fan, these algorithmic recommendations speak to us with the authority of data. Yet unlike the automated recommendations produced by Amazon's "Books You May Like" feature, for example, the recommendations in BookTok videos are delivered by people who identify as fellow readers, and who embed the pleasure and performance of reading into their recommendations. Because the TikTok recommendation system serves up BookTok videos to interested users and not just an endless list of book recommendations without any contextualization, BookTok recommendations feel more like asking a friend what they think you might like and why. This powerful combination — a parasocial algorithmic recommendation system — is an important element of BookTok's success as a marketing powerhouse for the publishing industry.

This recasting of literary recommendation is often dismissed by journalists and academics because of BookTok's association with young women. In addition to romance, genres stereotypically associated with younger female readers — such as Young Adult (YA) fiction, YA fantasy, and mystery — also dominate BookTok.6 Like fiction readers more generally, BookTok demographics skew younger and more female, and while many men and creators of color post BookTok videos, many of the most popular BookTok creators are white women. This is reflected in the BookTok content I examined for this piece: the majority of viral BookTok videos that I collected, via a process explained below, is posted by white-presenting and female-presenting creators. Moreover, some of the BookTok videos I collected participate in an aesthetic closely related to that of pale blogging, a practice popular on Tumblr in the mid-2010s that Christine Goding-Doty has defined as "a genre of digital youth culture . . . that glorifies all things #pretty and #pale."7 As Goding-Doty writes, pale blogging "redefin[es] traditional symbols of white hegemony through associations with beauty and ethereality or weakness."8 On BookTok this can include, for example, videos that begin with an overexposed close-up of the side of a young woman's face with all distinguishing features cropped out except for her white skin and ear, which is usually full of earrings, or videos featuring writing prompts accompanied by an otherworldly soundtrack and set against a beautiful natural landscape empty of people.

Press coverage of BookTok contributes to this association with young white women by repeatedly emphasizing the degree to which videos focus on creators' emotional responses to the books they read. For example, one article in the Washington Post about Colleen Hoover's popularity on BookTok emphasizes that while "generations of people have been taught that public displays of weeping are the height of embarrassment," on BookTok, "crying is commonplace."9 And a piece in the London Review of Books barely contains its mixture of contempt and bemusement at the "highly emotional" and "chaotic" videos in which "BookTokkers scream, cry, and throw up their way through books."10 However, the press's fascination with videos of people sobbing or screaming may have less to do with the overall "emotional" quality of BookTok videos themselves — especially when compared with other kinds of videos on TikTok — than with the fact that many of the people in these videos are women.11 The frequency with which newspaper or magazine articles about BookTok mention emotions, specifically crying, is therefore one way to index BookTok as a particular kind of feminine space: young, hysterical (but in a cute way 🥰), and predominantly white.

This framing also casts people who participate in BookTok primarily as consumers. It taps into long-standing associations between consumer culture and femininity, perpetuating a fantasy of consumption without production. This fantasy positions the reader as a feminized (implicitly white) figure of endless consumption. Conveniently for TikTok, this fantasy also undergirds their profit model, in which only the most influential accounts receive compensation for their work in powering the platform. As with other social media platforms, the act of posting videos falls under TikTok's terms of service, defining those who create content as "users" — or consumers — of a product. BookTok thus contributes to what Sarah Brouillette identifies as "the feminization of work in the publishing industry," meaning the "maximization of profits via the expansion of casualized labor and exploitation of unpaid activity by readers and writers."12

Many of the BookTok videos I collected and viewed are not "emotional" in this way, however. Most of these videos are recommendations — sometimes for specific books, but always for the act of reading. They give us some sense both of how TikTok works as a recommendation system and of how the platform itself affects BookTok's style of recommendation. They celebrate and, occasionally, throw into question the understanding of readers (and content creators) as only or primarily consumers. But attention to the rituals of recommendation on BookTok suggests we understand BookTok above all as a place where literary criticism — of a particular kind — is currently thriving.

***

To get a better sense of how recommendations work on BookTok, I scraped metadata for the top 500 videos tagged with the #BookTok hashtag as of August 10, 2022. I collected this data using a browser on my laptop and was not signed in to any of my TikTok accounts when I collected it. This gave me a small slice of viral BookTok videos trending on TikTok at that time. There is no public API for TikTok, so my research assistant, Owen Leonard, and I used a scraper that Leonard developed to collect this data (Leonard's scraper can be found on GitHub: https://github.com/owenleonard11/tiktok-scraper). We collected data about the first 500 videos returned from a search for "#BookTok." It remains unclear how TikTok orders search results or determines what constitutes a "top" video; view count is important, but the "top" videos returned for this search are not ordered by view count alone. However, while a video's virality increases the chances that it will be viewed, the method I chose — watching the top results returned by a specific search, one after the next — is not how TikTok was designed to be used. In fact, as I quickly discovered, watching BookTok videos in this way is intensely boring. Instead, the "magic" that many users have identified as being particular to TikTok — its uncanny ability to quickly discover the kind of content each user might enjoy watching and to customize its offerings accordingly — centers on the For You Page (FYP). The FYP is each user's "Home" screen, the place where users begin their experience of the app. When you first open an account, TikTok's recommendation system serves up popular as well as more random videos to get a sense of what you like. Depending on how you interact with those videos — if you watch them to the end, if you rewatch them, if you quickly swipe them away — it will send more of the same or try something else. Once it learns more about what you like, the system will reliably send you related videos, but it will also keep trying new stuff to see how you respond. This iterative process is how it learns to suggest videos "for you."13

To determine how the BookTok videos I encounter via my FYP might differ from the viral BookTok videos I collected, I created a BookTok-focused account and began watching videos. Signed into this account using the TikTok app on my cell phone, I searched for various hashtags related to BookTok and watched some of the results, followed known BookTok creators, watched in full every BookTok video that came across my feed, and swiped away non-BookTok videos as quickly as possible. I did this sporadically for about six months. Then, from late November to early December 2022, I conducted an audit of this account, keeping track of each video that came across my FYP by saving its URL, whether it was BookTok-related or not. After each viewing session, I used the Pyktok module — written by Deen Freelon with contributions from Philip Kreißel, Parker Bach, Timo Bäuerle, and Christina Walker — to scrape the metadata for each of the videos on this list of URLs (the Pyktok module can be found on GitHub: https://github.com/dfreelon/pyktok). After about two weeks, I had scraped data for 250 videos. Since I would see different kinds of videos if I accessed this account using different devices, I only saved the videos I accessed using my cell phone from my home wifi. All told, these data collection methods resulted in two datasets including metadata for about 750 videos: the top 500 videos scraped from a search for "#BookTok" (I refer to this data as the "Top" data in what follows), and 250 videos scraped from my BookTok account's FYP (I refer to this data as the "Account" data in what follows). Finally, I watched all of these videos, taking notes on their contents and manually sorting each one into larger overlapping categories I developed as I watched (e.g., "romance" for videos about romance fiction, "hoover" for videos about Hoover or mentioning one of her books, "bookshelves" for videos featuring shots of bookshelves, etc.).

This data is not representative of BookTok as a whole, as it's tied to a particular hashtag (BookTok videos do not always use the #BookTok hashtag, for instance) and to my BookTok-focused account's FYP. But it does allow us to ask questions about what BookTok looks like from these different vantage points. Each dataset includes an incredible variety of videos, ranging from more straightforward book recommendations and reviews to videos about crafting with books, building and organizing bookshelves, buying books, cosplay, reader reactions to "spicy" scenes in romance novels, cover reveals of creators' favorite or least favorite books, and much more.14

As we can see in Table 1, most of the videos in each dataset were posted by unique creators; most were posted in North America (specifically the United States) or Europe; and most feature audio, a caption, and/or video sticker text (the text that appears on the video itself) in English.15 There are no videos that appear in both datasets, and only 12 creators that appear in both. Table 1 also includes information about the length of videos. While the median video length in each dataset is the same at 15 seconds, the Account dataset has a greater distribution of video lengths. There are more videos in that dataset over 60 seconds long and under seven seconds long; video lengths in the Top dataset, in contrast, are clustered more densely around the median, with a majority of videos between seven and 25 seconds long. Videos in the Account dataset are also more concentrated around the time of data collection; they include videos posted from August 27, 2022, through December 8, 2022, while videos in the Top dataset were posted over a longer period of time, from August 2, 2020 through July 31, 2022.

| Category | Account (count, percentage of total) | Top (count, percentage of total) |

| Videos by unique creators | 189, 76% | 399, 80% |

| Videos posted in US | 161, 64% | 229, 46% |

| Videos posted in transcontinental (e.g., Russia), non-North American, or non-European countries | 3, 1% | 74, 15% |

| Videos in English (including audio, caption, and/or sticker text) | 250, 100% | 437, 87% |

| Videos over 60 seconds | 45, 18% | 29, 6% |

| Videos under 7 seconds | 39, 16% | 29, 6% |

| Videos between 7 and 25 seconds | 117, 47% | 299, 60% |

On the whole, the videos in the Top dataset have more likes, shares, comments, and views than the videos in the Account dataset. This isn't surprising given that the Top dataset is composed of viral videos. Creators in the Top dataset also tend to have more followers than creators in the Account dataset, though this contrast is less stark.16 This distinction emphasizes an important aspect of TikTok as a social media platform: compared to other platforms like Instagram or Facebook, its algorithm cares less about the number of followers a creator has when distributing content to FYPs. As others have reported, each video on TikTok is guaranteed an audience of at least a few hundred views, and then, if it does well with that initial audience, the algorithm sends it out to thousands of viewers, then tens and hundreds of thousands and more.17 This mode of delivery makes it easier for videos by creators with relatively few followers to gain popularity on the platform. But it also means that most of the videos that appear on users' FYPs are neither viral nor obscure. Indeed, the majority of videos that appeared on my account's FYP occupy this middle range of popularity.

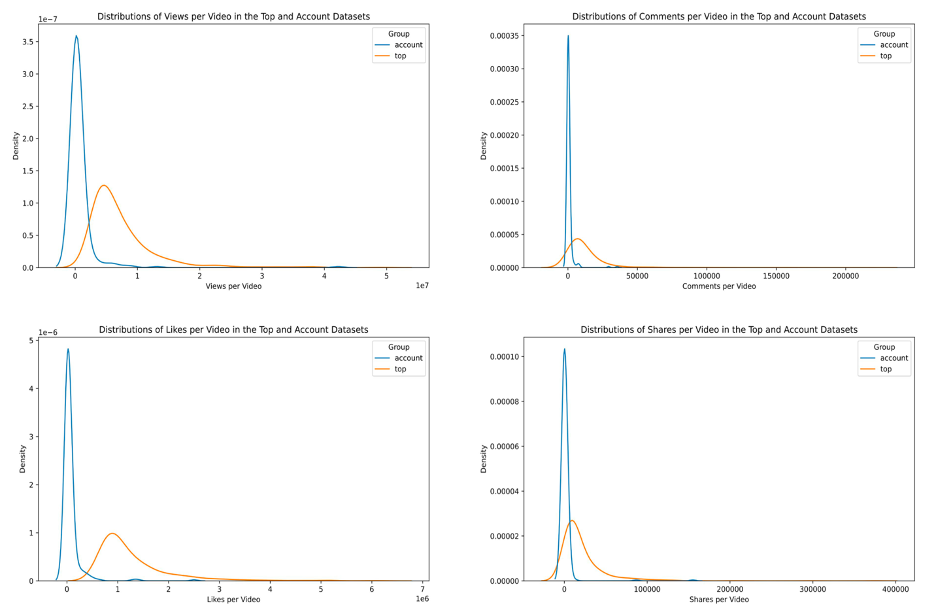

As Figure 2 indicates, when we compare the likes, shares, comments, and views values for videos in the Top dataset to those for videos in the Account dataset, we see that in each case values for the Account dataset are more tightly clustered around the median than values for the Top dataset.18 Additionally, in each case, these median values in the Account dataset are significantly lower than the median values in the Top dataset. In other words, in the Account dataset, a higher proportion of videos have relatively lower numbers of likes, shares, comments, and views than in the Top dataset. At the same time, these values are high enough to suggest that thousands or tens of thousands of people had already liked, shared, commented on, or seen the video before it showed up on my FYP (Table 2). The Account dataset also includes a few outliers on either end of each spectrum for each of these metrics, indicating that the algorithm occasionally mixes in content that is already very popular or content that is still in the initial stages of delivery to FYPs. For example, 17 videos in the Account dataset (7% of total) have been viewed at least 1.9 million times, which is the lowest view value for videos in the Top dataset. At the other end of the spectrum, six videos in the Account dataset (2% of total) have fewer than 500 views, and almost all of these videos appeared on my account's FYP within 24 hours of posting (one appeared three days after posting). These numbers — and TikTok's emphasis on that middle range of popularity in which content is popular enough to have a good shot, statistically, of being liked, but not so popular that it risks feeling generic — speaks to a core aspect of user experience on the platform. Even when watching a popular video, you don't necessarily have the feeling of participating in mass culture, or in something broadly shared. However popular a given video may in fact be, the algorithm's recommendations continue to feel personalized: not "for everyone," but "for you."

| Category | Account | Top |

| Minimum views per video | 162 | 1.9 million |

| Median views per video | 176,850 | 5.6 million |

| Maximum views per video | 42.2 million | 49 million |

| Minimum comments per video | 0 | 0 |

| Median comments per video | 171.5 | 7710.5 |

| Maximum comments per video | 35,400 | 217,900 |

| Minimum likes per video | 7 | 702,800 |

| Median likes per video | 22,600 | 1 million |

| Maximum likes per video | 2.5 million | 6.1 million |

| Minimum shares per video | 1 | 155,100 |

| Median shares per video | 80 | 11,700 |

| Maximum shares per video | 342 | 373,700 |

This emphasis on specific yet "popular enough" content creates a feeling of serendipity when scrolling, as if the viewer has just happened upon something they like without seeking it out. This sense of effortless discovery contributes to the "magical" feeling of TikTok, where brand-new users can begin "stumbling across" content that seems tailor-made for them. It also contributes to the proliferation of niches or "sides" on the platform. This means that BookTok is not just one thing, as there are many different sides of BookTok. For this reason, while talking about "BookTok books" or "BookTok authors" is useful shorthand, it is also misleading, as there is an endless variety of books and authors discussed on the platform.

We can glimpse some of this variety when comparing the kinds of books mentioned in the Top dataset to those mentioned in the Account dataset. For example, videos mentioning fantasy books, "classics," and — somewhat surprisingly to me — romance and Colleen Hoover books are more likely to appear in my Account dataset, whereas videos mentioning the Harry Potter series are more likely to appear in the Top dataset.19 Videos in the Top dataset also mention books or franchises that aren't mentioned at all in the Account dataset, and vice versa. For example, 21 videos in the Top dataset mention reading stories on Wattpad, the online platform where users read and write original stories, 16 mention the Twilight franchise, and 12 mention the recent Netflix adaptation of Jenny Han's popular 2009 romance novel The Summer I Turned Pretty. Videos mentioning these things do not appear at all in the Account dataset. Likewise, I tagged seven videos in my Account dataset as mentioning examples of contemporary literary fiction, while no videos in the Top dataset mention examples of this genre.20 TikTok, then, seems to know a few things about me, or at least about the "me" using my BookTok account: it knows I like books and it knows my gender, certainly, but it also perhaps has guessed that I am more likely to enjoy watching videos about "classics" or literary fiction than I am about Harry Potter or Twilight.

Videos in the Account dataset are also more likely to be book recommendation videos, or videos oriented toward encouraging viewers to read — or sometimes not to read — the specific books mentioned in the video. For example, in the Account dataset, I tagged 64 videos (26% of total) as book recommendations, while in the Top dataset, I tagged 63 videos (13% of total) as book recommendations. The chance that a recommendation video is included in the Account dataset is therefore about twice that for the Top dataset.21 These recommendation videos, however, are not so much about the quality of the books being recommended as they are about the creator's opinions and tastes (and, yes, emotions).22 One trend, for example, features audio of a woman sobbing and gasping out the words "why would you write this book?" while creators display the covers of books that, as one puts it, "ripped my heart to shreds."23 In another, creators post lines from a book in a video's sticker text and film themselves reacting to the lines. In several of the examples of this trend from the Top dataset, for example, creators react to lines quoted from sex scenes by raising their eyebrows and smiling or putting their hands up to their mouths in enjoyment and faux shock. Videos can be negative in tone as well. In a video from the Account dataset, the creator points to the image of a book cover while, in the background, a popular sound plays the question, "what is the one book that if you see somebody recommend, you instantly don't trust their recommendations?"

In addition to dramatizing creators' preferences and emotional responses to books, recommendation videos also frequently focus on the tropes or other features that books contain (which the creator either likes or dislikes). One video, for example, recommends V.E. Schwab's Shades of Magic series by emphasizing, in the sticker text, how the series "has the VERY BEST TROPE in it. The trope where she's fighting but then gets injured and he absolutely loses it and risks it all to get to her." Videos featuring creators' "top five, all-time favorite reads" or "books with fae and spice 🔥 that were unputdownable" are also emblematic. While creators still assess and evaluate books in these videos, their judgments turn less on aesthetic endorsement than on typology, including the type of book that they are and the type of reader that might enjoy them.24 For example, the creator who posted the video about her "top five, all-time favorite reads" emphasizes in this video that the books on this list are those "that I have read multiple times, that have been with me in difficult times," and she identifies many of the books she recommends as "comfort reads." If you, like the creator of the video, are someone who enjoys comfort reads, well, then you might like these books. This style of recommendation depends not necessarily on standard markers of cultural authority such as the professional training of the recommender — because most creators posting videos on BookTok don't generally have such forms of authority — but rather on the presumed alignment of the tastes and preferences of the viewer with those of the creator.

This mode of recommendation, like TikTok itself, also encourages the feeling of discovery and serendipitous encounter. Its tone and form of recommendation recall the handwritten notes found in many bookstores posted below featured or "Staff Recommended" books exhorting readers to try those books if they like another closely related book or if they enjoy that particular genre. The judgments on display in this mode of recommendation are associative (from person to person, and book to book) rather than absolute. Such recommendations may be designed for the casual browser, for those who come into the bookstore to kill time, to see what's new, or just to poke around. People use apps like TikTok for these reasons, too. "If you like X, then try Y" is the form of recommendations made by recommendation engines, which recommend new things to users based on past behavior. In this way, the associative nature of BookTok recommendations resonates with existing algorithmic structures of recommendation. This is also how presumed information about a user's gender and race can get baked into a user's FYP algorithm, even though TikTok does not explicitly collect such information. If you are someone whose "tastes" and "preferences" align with those of the people making the videos you watch, you will be shown more videos aligned with these "tastes" and "preferences."25 While being shown videos you like on TikTok may feel as serendipitous as finding your new favorite novel by an author you've never heard of in a bookstore you've never been in before, this feeling is manufactured by TikTok as part of the user experience.

Interestingly, the majority of BookTok videos I watched, from either dataset, do not recommend specific books per se. Remember, I tagged only 64 videos in the Account dataset as book recommendations (26% of total) and only 63 videos in the Top dataset (13% of total). Indeed, many of the videos I collected don't even mention specific books.26 Rather, these videos focus on the act of reading and on the creator's identity as a reader. In addition to posting videos of themselves reacting to favorite lines or scenes in novels, creators post videos that embrace reading as their favorite activity. In one video in this vein, the creator holds up a stack of books while lip synching to the part of the song "I'm Good (Blue)" that includes the line, "I'ma have the best fuckin' night of my life." The sticker text for this video reads, "when you're about to do zero socializing and read for the next 14 hours with a bag of chips and zero shame." Other videos feature cosplay, as creators dress up as their favorite Twilight characters or even as an imagined character type like "fantasy heroine who is a sorceress and also a skillful horse rider and archer." Still other videos are only vaguely bookish in that they feature images associated with various recognizable plot lines or tropes or "aesthetics" associated with particular genres, characters, or kinds of readers. For example, one video like this begins with the sticker text, "The tragic plot line you'd have based on your star sign," and then features images evocative of such plot lines and their associated star signs, including "betrayed by their lover" (Leo), "fell in love with the right person at the wrong time" (Cancer), and "destroyed themselves trying to please everyone else" (Pisces). Other videos communicate something like a "BookTok vibe" recognizable to those familiar with BookTok without being about any specific books, genres, characters, or tropes. One example features shots of several ornate, gothic daggers evocative of a dark fantasy aesthetic with the caption "What your girl really wants for valentines day 😏." All of these videos draw generalizations, whether forming typologies of characters or ritualized actions, and most explicitly serve BookTok's governing trope: the character type of "the reader." Even if they don't mention any specific books, they all recommend reading itself.

To be on BookTok, then, is to watch a lot of videos about the joys of reading and of belonging to a community of readers. A cynical view of these joys, one shared by the publishing industry, might recognize BookTok as one of the greatest advertising platforms in the history of publishing. BookTok combines the persuasive power and parasocial affect of word-of-mouth advertising with the reach, relative ease of access, and consumer targeting of social media. It's therefore no surprise that Barnes & Noble has jumped aboard the BookTok train, or that BookTok videos sometimes feature creators shopping for books at Barnes & Noble.27 Other "book haul" and "unboxing" videos feature creators showing off their latest purchases, whether from a physical store or online. These videos are a reminder that the physical book, specifically the trade paperback, is the preferred format for reading on BookTok. In video after video, creators caress their covers, flip through their pages, stack them on top of one another, and break their spines (or react in horror when other people break their spines).

The physical book is also an essential marker of the identity of "being a reader" on the platform. As Ted Striphas has emphasized, "books — along with sewing machines, pianos, and furniture — were among the very first items that people purchased with . . . consumer credit," and as such, are emblematic of the shift toward consumer capitalism in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.28 BookTokkers' interest in owning physical books is therefore also part of BookTok's nostalgic charm. Collecting physical books feels out of step with a time in which everything is on demand but only by subscription. Under the regime of what Striphas has identified as "controlled consumption," consumers pay for limited access to books, music, and movies rather than purchase them outright.29 This is the business model behind popular streaming services like Spotify and Netflix and, in publishing, behind services like Kindle Unlimited. Under this subscription model, consumers can access more content than they would ever own themselves, so long as they continue to pay for the service or platform that owns or has purchased the rights to this content (or so long as that service or platform exists).

In contrast, BookTokkers who purchase paperbacks are not beholden to any service or company for the ability to access these books. Many videos on BookTok project a world in which modest material comforts — not only the extra money to buy books but also the space in which to store them and the time in which to read them — are still possible. This is a throwback world in which book buying, particularly purchasing fiction, still functions as a marker of white middle-class belonging (and belongings). The sentimental white feminine aesthetic produced by some BookTok videos and emphasized repeatedly in press coverage of BookTok is also, then, aspirational. In making middle-class whiteness available as a diffuse, amorphous aesthetic, these videos project a world in which this vision of comfort and consumerism is seemingly available to anyone — as long as the look is correct.

But this economic and compensatory framework cannot fully account for how BookTokkers engage with physical texts. While even BookTok videos not explicitly about buying books are nevertheless often implicitly about owning them, they are also often about what one can produce and create with all of these books.30 They feature shots of creators' bookshelves or fantasy libraries, or they show them assembling book nooks, binding books, or painting their fore-edges. Some videos also include shots of crammed bookshelves, tours of aesthetically pleasing stacks of books arranged on the floor and on stairways, and time-lapse sequences of creators building their own bookshelves or reading an entire novel in one day. Others still emphasize how creators tag their books, a practice that involves annotating and attaching sticky notes to particular pages to help them remember important or meaningful passages. Some videos also feature shots of the supplies creators use for tagging books.

These videos make visible the labor of reading, interacting with, interpreting, and handling books. They distill hours or days of reading into just tens of seconds of carefully edited footage, reminding us that the labor of literary criticism is time intensive. They also remind us that this labor is highly innovative, as creators constantly work within and stretch the constraints of the medium to invent new ways to talk about, interpret, craft with, handle, and display books. And finally, this labor is often a labor of love. While some creators garner brand deals and paid sponsorships to fund their BookTok creations, most do not. Their literary criticism, as Aarthi Vadde writes about engagements with contemporary digital publishing more broadly, "functions as a gift through [the] platform's interface with users," even while it also functions "as a commodity behind that interface," in this case, for both publishers and TikTok.31

Like any work of literary criticism, BookTok videos are crafted expressions of meaning, knowledge, and emotion gained through reading. In making visible the labor required to produce these insights, many BookTok videos present the figure of the reader as a producer as well as a consumer. Yet this emphasis on the work of reading is happening in a moment when the forms of financial and institutional support that have made literary criticism possible in the past are increasingly inaccessible or simply disappearing. From this perspective, the flourishing of literary criticism on BookTok is one more symptom of the failure to materially support this work elsewhere. But we can also understand it, for as long as it lasts, as an opportunity to reexamine the work of literary criticism. The kind of literary criticism that flourishes on BookTok is one in which critical judgments are essentially social and associative rather than evaluative: if you like this, then try that; if you're the kind of person who enjoys that, then give this a go. Such typological criticism is never free from the conditions of this "if then" structure of recommendation, making absolute evaluations difficult and undesirable. But this kind of criticism also reaches ever outward, seeking others who share these conditions. BookTok helps us understand that all literary criticism is beholden to such conditions and associations, even when masked behind more stringent or complicated assessments. The infectious joy (and occasional sorrow) of many BookTok videos makes this tendency toward typological criticism more visible and more attractive, yet it should not strike us as entirely unfamiliar. To engage in any act of literary criticism is to seek association, to categorize and sort, and to create community.

Lindsay Thomas (@lindsaycthomas , @lindsaycthomas.bsky.social) is Associate Professor in the Department of Literatures in English at Cornell University. She is the author of Training for Catastrophe: Fictions of National Security after 9/11 (Minnesota, 2021).

References

- Acknowledgments: Thank you to Sarah Brouillette and Susanna Sacks for their invaluable comments on earlier drafts of this essay.

As J. D. Porter, Angelina Eimannsberger, James English, May Hathaway, and Ashna Yakoob write, "romance is the juggernaut of contemporary literature, standing out from all other genres in its sheer scale and in the wild diversity of its subgenres." See Porter et. al., "Genre Juggernaut: Measuring 'Romance,'" Public Books (November 10, 2023), unpaginated. For more on the popularity of contemporary romance as a genre, see Sarah Brouillette, "Romance Work," Theory & Event 22, no. 2 (2019): 451-464. [⤒]

- Marty Swant, "Inside Penguin Random House's play to reach avid readers on TikTok's BookTok," Digiday, (September 22, 2022), unpaginated. [⤒]

- The many profiles of Hoover in mainstream media outlets over the past two years are evidence of this success. Just a few examples include Stephanie McNeal, "How Colleen Hoover Became the Queen of BookTok," BuzzFeed News (July 7, 2022), unpaginated; Laura Miller, "The Unlikely Author Who's Absolutely Dominating the Bestseller List," Slate (August 7, 2022), unpaginated; and Kayleigh Donaldson, "Relentless Angst and Uniformly Excellent Sex: How Colleen Hoover Became the Queen of BookTok," Vulture (October 25, 2022), unpaginated. [⤒]

- "Top 10 Books," NPD (December 5, 2022), unpaginated. [⤒]

- For more on algorithmic recommendation systems and their relation to cultural industries, see Ted Striphas, "Algorithmic Culture," European Journal of Cultural Studies 18, no. 4-5 (2015): 395-412. [⤒]

- Sophia Stewart, "U.S. Book Show: How TikTok is Transforming Book Marketing," Publisher's Weekly (May 24, 2022), unpaginated. [⤒]

- Christine Goding-Doty, "Beyond the Pale Blog: Tumblr Pink and the Aesthetics of White Anxiety," in a tumblr book: platform and cultures, eds. Allison McCraken, Alexander Cho, Louisa Stein, and Indira Neill Hoch (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2020), 344. [⤒]

- Goding-Doty, "Beyond the Pale Blog," 346. [⤒]

- Stephanie Merry, "On TikTok, crying is encouraged. Colleen Hoover's books get the job done," Washington Post, January 20, 2022.[⤒]

- Malin Hay, "BookTok," London Review of Books 45, no. 2 (January 19, 2023). [⤒]

- For example, among the 750 BookTok videos I collected and viewed, 7 featured video, images, or audio of someone sobbing. [⤒]

- Sarah Brouillette, "Wattpad's Fictions of Care," Post45: Peer Reviewed (July 13, 2022), unpaginated. [⤒]

- For more on how the TikTok recommendation system works, see Arvind Narayanan, "TikTok's Secret Sauce," Knight First Amendment Institute (December 15, 2022), unpaginated. [⤒]

- Code for the below analysis is available upon request. [⤒]

- BookTok videos in other languages often use different hashtags; for example, #librostiktok and #booktokespañol are two popular choices for BookTok videos in Spanish. [⤒]

- The difference between the median video view values across both datasets (5,423,150) is two orders of magnitude greater than the difference between the median creator follower values across both datasets (79,500). The median video view value of the Account dataset is only about 3% of the median video view value of the Top dataset, while the median followers per creator of the Account dataset is 26% that of the Account dataset. [⤒]

- Alex Kantrowitz, "I Learned TikTok's Traffic Secrets in Three Weeks. Here's the Cheat Sheet," Observer (October 25, 2022), unpaginated. [⤒]

- Kernel density graphs provide an overall view of the "shape" of the distribution of values for each variable in both datasets. The x-axis represents the number of views, comments, shares, or likes per video, and the y-axis is a representation of the density of distribution for each value on the x-axis (e.g., of about how many videos in the dataset have 5 million views, of about how many have 10 million views, etc.). A higher density value indicates a greater number of videos at the corresponding value on the x-axis. The peaks of each graph represent the median value for each variable in each dataset. [⤒]

- Fantasy books are about two times as likely to appear in the Account dataset as the Top dataset (Top: 19 videos, Account: 20 videos); videos mentioning "classics" are eight times as likely to appear in the Account dataset as the Top dataset (Top: two videos, Account: eight videos); romance books are about 1.4 times as likely to appear in the Account dataset as the Top dataset (Top: 171, Account: 62); and videos mentioning Colleen Hoover books are 1.9 times as likely to appear in the Account dataset as the Top dataset (Top: 19 videos, Account: 18 videos). Videos mentioning Harry Potter are 7.5 times as likely to appear in the Top dataset as the Account dataset (Top: 15 videos, Account: one video). These observations are based on risk ratio calculations I performed across the two datasets (risk ratio = percentage of videos of a particular kind in one dataset divided by percentage of videos of that kind in the other dataset). [⤒]

- Six of the seven videos I tagged as mentioning examples of literary fiction include at least one title by a non-white author; this is a much higher rate of videos that include titles by non-white authors than in videos not tagged as including examples of literary fiction. [⤒]

- This number is also based on a risk ratio calculation comparing these two datasets. [⤒]

- The Account dataset is also, however, more likely to include reviews of specific books. In videos I tagged as book reviews, the content of the books being reviewed does matter. In general, book review videos are oriented toward describing the books mentioned in the video rather than toward expressing the creator's reactions or preferences. I tagged 14 videos in the Account dataset as book reviews, and only 2 in the Top dataset as reviews (I tagged 5 videos in the Account dataset as both reviews and recommendations). [⤒]

- I have elected not to provide full citations of the TikTok videos I discuss nor to identify creators by username within this piece in accordance with norms in fan studies, wherein it is general practice not to include full citations (or sometimes even links) to people's social media posts. While BookTokkers are not always or necessarily fans, I see BookTok as a kind of fan space. Especially, as in this case, when the specific posts discussed exemplify general trends and typologies and the arguments do not depend on any one post or creator in particular, links and description are preferred to excessive citation. Though the videos I link to are discoverable and nominally public, this practice provides some protection for creators, as they could elect to remove any videos linked here. It also recognizes the essentially ephemeral nature of social media and the discourse that happens there, as over time, the links to at least some of the videos will degrade. For more on evolving practices in fan studies, see Katherine Larsen, "Where we are," Journal of Fandom Studies 4, no. 3 (2016): 229-31. Citations for any videos discussed are available upon request. [⤒]

- This style of recommendation is not specific to BookTook or to algorithmic recommendation systems more generally. As Janice Radway has argued, engines of mid-twentieth century middlebrow culture such as the Book of the Month club thought about book recommendations in this way. "Book-of-the-Month Club judges," she writes, "tended to subordinate the critical act of literary judgment to the activity of recommendation," which they saw as "a self-consciously social activity constituted by their effort to understand and to adopt the point of view of their subscribers." See Radway, A Feeling for Books (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 271. [⤒]

- Nick Seaver argues that user demographics function in algorithmic music recommendation systems "not as an essential quality of a listener but as a kind of maybe-relevant context, analogous to the fact of being at the gym or listening in the evening." See Seaver, Computing Taste: Algorithms and the Makers of Music Recommendation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022), 92. [⤒]

- Though more videos in the Account dataset (137 videos, 55% of total) mention specific titles than in the Top dataset (105 videos, 21% of total). [⤒]

- This kind of video showed up in both datasets, though it is not all that common in either. I tagged seven videos in the Account dataset as being about buying books at Barnes & Noble (3% of total), while I tagged eight videos in the Top dataset in this way (1.6% of total). [⤒]

- Ted Striphas, The Late Age of Print: Everyday Book Culture from Consumerism to Control (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 8. [⤒]

- See Striphas, The Late Age of Print, especially the conclusion, "From Consumerism to Control." [⤒]

- Many BookTok videos are yet one more example of what Jessica Pressman has identified as bookishness, or "creative acts that engage the physicality of the book within a digital culture, in modes that may be sentimental, fetishistic, radical." As Pressman emphasizes, "'bookishness' suggests an identity derived from a physical nearness to books, not just from the 'reading' of them in the conventional sense." See Pressman, Bookishness: Loving Books in a Digital Age (New York: Columbia University Press, 2020), 14, 26. [⤒]

- Aarthi Vadde, "Amateur Creativity: Contemporary Literature and the Digital Publishing Scene," New Literary History 48, no. 1 (2017), 33. [⤒]