My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

Philadelphia, PA

Dear Diana, Cecily, and Dan,

I've always remembered things in colors rather than forms.

My earliest memory takes place in Bed Stuy in a brownstone off the A train, a few blocks away from Boys and Girls High School, called this because it's the product of a merger between Boys High School and Girls High School, two prestigious public institutions that have a number of famous alumni—Isaac Asimov, Shirley Chisholm, Aaron Copland, Rita Hayworth, Lena Horne, Norman Mailer, and my father, to name a few—but went into decline when they moved into a new building on Fulton between Utica and Schenectady. I'm about three and my mother is cooking pasta (or is it boiling greens?). Mom picks up the pot and spills some of the water (or the pot slips out of her grasp?) and some of the boiling water splashes onto my baby legs, right above the knee. In this memory, I feel nothing but the vivid red where the water is burning my flesh and pulsating with an intensity akin to anger but it couldn't possibly be that. Water can't have emotions and my mother wasn't flinging hot water at her child maliciously. In this memory, when I'm not looking down at my leg, I'm looking at the walls around me, seafoam green.

I've reconstructed this non-memory memory (psychology tells us we don't remember anything before the age of five, after all) countless times. I still have a scar that kind of looks like the continental US that has faded and faded as I've gotten darker and darker but has never actually gone away. That scar reminds me that the only things I'm ever certain about of that evening (afternoon? late night?) are a red as vibrant as the ink in the pen I'm using to write this letter and seafoam green. It'll sound strange but this event has always made me dubious of the autobiographical novel, the semi-autobiographical novel, the memoir. If I can't remember something that has literally scarred me for life, how can anyone else remember anything at all?

My skepticism of other people's memory has been both heightened and restrained in my reading of My Struggle. It's fed by little moments that reveal an inherent contradiction. My Struggle is, at its most basic level, an exercise in recollecting the mundane, but after acknowledging his indebtedness to Proust, K makes the ridiculous statement that "the past is now barely in my thoughts" (29-30). A page after he remembers seeing an image of a face in the sea as a kid and five pages after the end of a long section cataloging minor events of his childhood, K confesses that "apart from one or two isolated events that Yngve and I had talked about so often they had almost assumed biblical proportions, I remembered hardly anything from my childhood" (191).

I'm going to get my jollies in with the rest of the popular reviewers of this novel and say that some of it feels so real—what you're calling the reality effects, Diana—that perhaps my issues with memory really don't matter. The extended exposition on what happens after a parent dies—the hyperpresent of making funeral arrangements bristling violently against the longue durée of a strained relationship with the dead—is real even if it's not accurate. All of the filth in the second part of the novel is probably real, too—metaphorically if not literally.

One of my favorite scenes in which the present and the past intersect occurs soon after K is informed of his father's passing:

Should I beat off?

No for Christ's sake, Dad's dead.

Dead, dead, Dad was dead.

Dead, dead, Dad was dead. (233)

Okay, but why not though? What makes jerking off an unacceptable way to grieve? When so much about masculinity is at stake with the death of the father and the writing of this novel, why not succumb to base male sexual desire in the face of pain?

There are only two modes by which K processes death: through action and through philosophy. Of course, K cries. K cries a lot. But crying operates as something other than an outward sign of inconsolable sadness. Rather, it often seems to be a response to frustration with not knowing how to react to such an event. The filth in Grandma's house provides K with a coping mechanism because if he wasn't mindlessly cleaning piss and shit from a bedroom floor or throwing plastic bottles out, he might actually have to encounter and manage the set of complex emotions that erupt when a family member passes. On the day he sees his father's corpse, K cuts the grass and succumbs to a crying fit. But, he doesn't know what it's about:

...tears flowed down my cheeks without cease, for Dad, who had grown up here, he was dead. Or perhaps that was not why I was crying, perhaps it was for quite different reasons, perhaps it was all the grief and misery I had accumulated over the last fifteen years that had now been released. It didn't matter, nothing mattered, I just walked around the garden cutting the grass that had grown too tall (415-416)

I think about toxic masculinity in moments like these. We often treat stoicism as if it's a universally healthy masculine trait rather than situational at best and indicative of a puerile inability to attend to that which we cannot rationally explain away. I thought K's crying would lead to a break from this aspect of traditional masculinity. I thought that the guy whose earliest childhood memory inexplicably involves Henrik Ibsen would offer us something other than another man who will ask himself why he is so emotional (repeatedly) but not actually answer the question. This, perhaps, is even more frustrating because K displays all of the sensitivity of a new man without the reflection and it's interesting to think that the only thing that K the author doesn't want to reveal too much about is why he cries so frequently when his father passes away.

K begins My Struggle with thoughts on two things: death and his father. His impression of death feels radically unchanged by the end of this first volume, but it's obvious that his relationship with his father is volatile at best, changing with every waking moment. One second his father is the middle school teacher and stamp collector who is a bit distant and confused by his young child's Christianity; the next moment he's a barely functioning alcoholic overwhelmed by the body's regular processes. And this may be where I become most critical: what does this novel tell us about death? Take K's last existential meditation on the end of life. After returning by himself to see his father's body, inexplicably covered in blood after what allegedly had been a peaceful death, K registers an affective absence that allows him the space to properly deal with what has happened:

Now I see his lifeless state. And that there was no longer any difference between what once had been my father and the table he was lying on, or the floor on which the table stood, or the wall socket beneath the window, or the cable running to the lamp beside him. For humans are merely one form among many, which the world produces over and over again, not only in everything that lives but also in everything that does not live, drawn in sand, stone, and water. And death, which I have always regarded as the greatest dimension of life, dark, compelling, was no more than a pipe that springs a leak, a branch that cracks in the wind, a jacket that slips off a clothes hangar and falls to the floor (441)

K's father's body takes on forms that make it not worth remembering. I don't remember what the pot that spilled the water that scalded me looked like. I have no idea what my mother was wearing. These details are so inconsequential to that memory that I could make them up (it was a 5 quart stainless steel pot and she wore a yellow blouse, acid wash jeans, and an apron that said "The Last Time I Cooked hardly anyone got sick"). It's those colors that made an impression. Without them, this scar would be a birthmark, unremarkable. I don't believe it when he says that the death of his father simply represents one form among many. Sure, he talks about the pedestrian inevitability of death multiple times; death is the kitchen table you sold on Craigslist for $25, bring your own pickup truck. But it's clear that this particular death contains multitudes; he would have choked the chicken if it didn't.

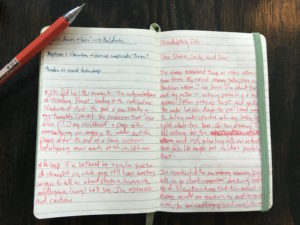

"Actual apron"

Maybe this is what coping with death looks like. Just before coming to this final realization, K's father's body haunts him and what had previously been the mundane fact that death was everywhere suddenly becomes the terrifying truth that DEATH IS EVERYWHERE. When death is as omnipresent as that discardable furniture, it transforms grieving into a manageable process. This observation, however, does call into question the work of mourning as a reasonable practice. Crying over a leaky pipe is unbecoming. Lamenting over a broken tree branch is unseemly (unless you're a Romantic poet, of course). I wonder if K wants a tidy grieving process because he wants to stop asking himself about why he cries.Maybe that's an unfair question.

Why won't you masturbate, K?

There's a better one.

Yours,

Omari

ALSO IN THIS SERIES:

The Slow Burn, v.2: An Introduction

My Struggle, vol. 1: Cecily, June 6

My Struggle, vol. 1: Diana, June 9

My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

My Struggle, vol. 1: Dan, June 17

My Struggle, vol. 2: Omari, June 24

My Struggle, vol. 2: Cecily, July 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Sarah Chihaya, July 5

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

My Struggle, vol. 2: Diana, July 16

My Struggle, vol. 2: Jess Arndt, July 18

My Struggle, vol. 3: Omari, July 25

My Struggle, vol. 3: Ari M. Brostoff, August 1

My Struggle, vol. 3: Dan, August 4

My Struggle, vol. 3: Jacob Brogan, August 8

My Struggle, vol. 3: Diana, August 12

My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25

My Struggle, vol. 4: Omari, September 1

My Struggle, vol. 4: Dan, September 2

My Struggle, vol. 4: Diana, September 15

My Struggle, vol. 5: Omari, September 27

My Struggle, vol. 5: Diana, October 3

My Struggle, vol. 5: Dan, October 13