My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

Ithaca, NY

Dear Diana, Cecily, Omari, and Sarah,

"The summer has been long," writes Knausgaard, "and it still isn't over" (3). We, too, are living through a long, hot summer. But, locked within himself, Karl Ove didn't mean this. In the last few days, police killed Alton Sterling and Philando Castile, two black men in separate incidents, caught on video, murderous acts. Castile was my age, from my city, graduated high school with friends of mine—but I'm white. I've been pulled over twelve times in those same neighborhoods and never gotten so much as a ticket. He's dead—over a broken taillight.

America's streets are boiling over. I woke up this morning to the news that a shooter killed five police officers in Dallas. The New York Post, reliably sensationalist, calls it a civil war. All against the backdrop of Clinton versus Trump, the political spectacle of our lifetimes.

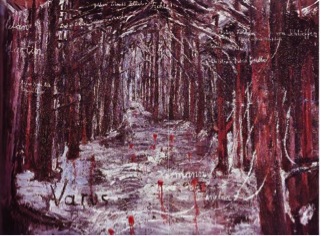

How odd, how wrong it feels, to immerse myself in the world of a man whose aesthetic project is to recapture "the wonder-rooms of the Baroque age. The curiosity cabinets. And the world in Kiefer's trees" (550). At some point, it seems, we're going to have to face more squarely the politics of Knausgaard's Struggle. When will we be forced to engage the fact that Knausgaard, as my friend Thom reminded me over breakfast today, titled his book—about, among other things, wounded masculinity and hostility toward the welfare state—Min Kamp?

I can't say I'm going to do more than be oblique, though, here.

Deep breath.

Immersion.

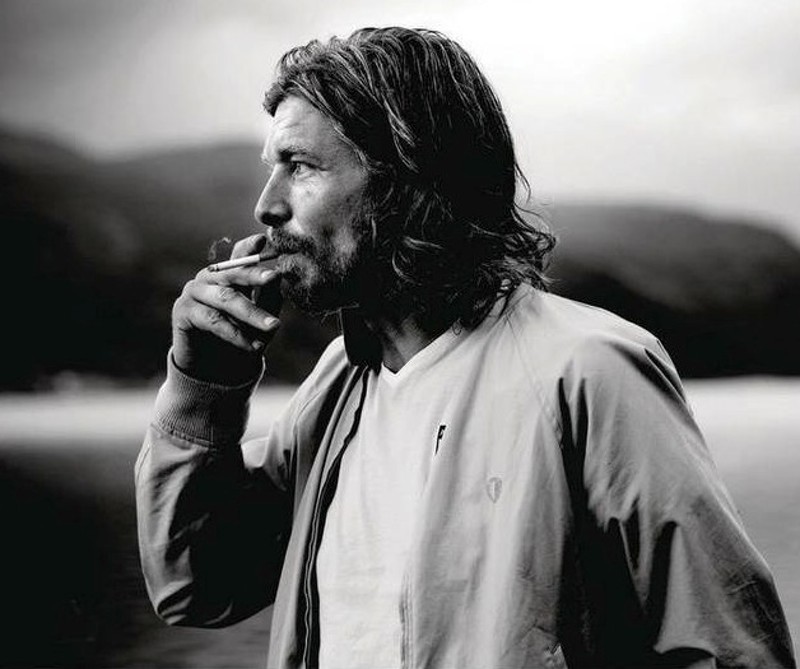

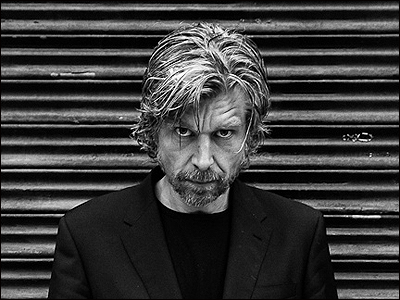

Kiefer's trees

I ask: are we supposed to like him? Are we—a naïve question, though I mean it—supposed to relate? Has this been, collectively, our tacit struggle? How difficult is it for us to disentangle our critical sensibilities from our feelings about the man when the text itself is, as Sarah posits, so much about his voice that it becomes about "the desire for the idea of voice"? Is Knausgaard knowingly heinous? How much irony distances "Knausgaard" the narrator from "Karl Ove" the protagonist? Is this Stephen Hero or A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man? Our letters, it seems, are marked by this ambivalence. We're trying hard to be generous. "Shouldn't I just open myself up to him," asks Omari, "and take him at his word?"

At his word, Knausgaard imagines himself something like a modern Norwegian Whitman: "I am you and you are everyone, we come from the same and are going to the same" (560). Oh, yes, we're supposed to relate—but Karl Ove's universalism of birth and death feels, for an American, at least, in 2016, startlingly anachronistic. Who's included in Karl Ove's "we"? Definitely not immigrants, not women, not people of color. Not even Swedes! Yet he aspires for the particularity of his experience to triumph over difference. Well.

I'm going to explore what happens if I dive head-first into Karl Ove's particularity, if I take Knausgaard, perversely, as my life coach. K as self-help guru. All I need to do is follow three simple steps: (1) Be a Man; (2) Be Good; (3) Fall in Love.

- Be a Man

A good place to start, if you want to relate to Karl Ove, is to be a man. Even better: be a man who fails at masculinity, perform that failure, let it eat at you.

In seventh grade, I bought the Friends soundtrack and, eager to share it, brought it to school. In addition to the theme song by The Rembrandts—I'll Be There for You—it featured tracks from Hootie and the Blowfish, Toad the Wet Sprocket, and the Barenaked Ladies. I had been watching the show obsessively since its debut the year before and just assumed it was cool. It was not cool. It was, I learned, a show for girls. This was the moment, for me, that my peers began policing gender in earnest. My Friends soundtrack became fodder to mock me for weeks. Ashamed, I got rid of it, but I never stopped watching the show. I just kept it secret. And I started listening to the right kind of music, like Metallica's Ride the Lightning and the Stone Temple Pilots' Purple.Later on, I developed a taste for girl pop: Christina Aguilera, Gwen Stefani, and, yes, the Spice Girls. In public, I pretended to listen ironically, like it was an affectation. But it wasn't, I loved the stuff. So I felt hailed when Knausgaard asked, in reference to his friend Tore, "what do you say to have any impact on a man who at one time admired the Spice Girls? To influence a man who at one time wrote an enthusiastic essay about the sitcom Friends?" (563).

How, Karl Ove, do I be a man? Should I abandon Taylor Swift for Hölderlin, Rihanna for Knut Hamsun? The first section of vol. 2, an unbroken ninety-six pages, is a tour de force of wounded masculinity. His meticulous account of young Stella's birthday party alternates between observing the gendered socialization of the children and the adults. He measures himself against all the other men, usually finding himself lacking. A man with coarse features inspires Karl Ove to recall the delicious anecdote about the time his wife, very pregnant, got locked in the bathroom at a party, and someone had to kick in the door, and Karl Ove couldn't muster the courage, so a virile boxer did the deed and Karl Ove, emasculated, felt compelled to humble himself and thank the boxer. "I had been so cowardly as to let someone else do the job," he writes, "and all of that was visible in my eyes. I was a miserable wretch" (36). Now, measured against the coarse-featured man, Karl Ove sees himself as a "weak, trammeled man" who lives his life "in the world of words" (36).

To be a weak, writerly man—like me and Karl Ove and, dare I say, Adolf Hitler—is to look around and find oneself lacking. Trapped among his kind, fellow stay-at-home dads watching their kids at the park, Karl Ove spies men attempting to reclaim their masculinity, hilariously, by "snatching a couple of pull-ups on the bars while the children played around them" (74). Insecurity on such public display! Better yet, we watch Karl Ove squirm as he brings Vanja to Rhythm Time, a song-and-dance class for parents and their toddlers. "I wasn't embarrassed," Karl Ove confesses, "it wasn't embarrassing sitting there"—wait for it—"it was humiliating and degrading" (77).

How do I be a man? Karl Ove? How do I pull myself from this wreck of emasculation? If he gives us a mantra, something to aspire to, a goal for manhood, it's just this: be good.

- Be Good

I don't trust the injunction. It strikes me—when spoken by men for men—as smarmy, self-serving, caught up too often in a kind of pretended innocence, preemptive self-congratulation.

Be good is Karl Ove's refrain. After interrogating his habit of ogling women on the street, he tells himself, "I had to apply myself harder. Forget everything around me and just concentrate on Vanja during the day. Give Linda all she needed. Be a good person. For Christ's sake, being a good person, was that beyond me?" (91).

Again and again. After Geir tells him that he (Karl Ove) as an eighteen-year-old impregnated a thirteen-year-old, which Karl Ove denies but, to himself, can't rule out as untrue, he thinks, "All I wanted was to be a decent person. A good, honest, upright person" (167). And then again, much later, thinking again about how he abandoned Tonje, he tells Geir, "'what I thought was that I would have to do everything I could to become a good person" (495). And once more, after subjecting Vanja to a violent fit, he tries to "be patient, kind, friendly, good. Good. And that was what I wanted to be, all I wanted to be, to be a good father to the three of them" (565).

Be good. Be good. Be good. Be good. It's an aspiration, for Karl Ove, always desired but never achieved. Expressing it seems like an attempt to exculpate himself for himself and for us. He ogles other women, abandons his wife, loses his temper with his children, but he wants to be good. This is the smarminess. Forget my actions: my soul longs to be good. I'm good in here, in my heart. If I repeat it enough times, maybe you'll believe me?But no matter, everything will be excused if I fall in love.

- Fall in Love

This, after all, is the subtitle of our volume: A Man in Love. Karl Ove tells the story of falling in love with Linda, and then, as a father, with Vanja. Love is what time was for the first volume: it holds the keys to meaning. In my first letter, I wrote about how Knausgaard wanted to slow down time in order to make the world meaningful again. This time, his meditation on the world bereft of meaning leads to love. "I was head over heels in love and everything was possible, my happiness was a bursting point all the time and embraced everything. If someone has spoken to me then about a lack of meaning I would have laughed out loud, for I was free and the world lay at my feet, open, packed with meaning" (69).

"This state," upon falling in love with Linda, "lasted for six months"; it lasted "four weeks, maybe five," after Vanja's birth (70). And then, and then: "that passed, too, we got used to that, too, and I began to work" (70). He begins to work! Vanja is five weeks old and Karl Ove abandons her, and Linda, and moves into his office. And the thing is, this is when his prose really begins to take flight:

I was filled with an absolutely fantastic feeling, a kind of light burned within me, not hot and consuming but cold and clear and shining. At night I took a cup of coffee with me and sat down on the bench outside the hospital to smoke, the streets around me were quiet, and I could hardly sit still, so great was my happiness. Everything was possible, everything made sense. At two places in the novel I soared higher than I had thought possible, and those two places alone, which I could not believe I had written, and no one else has noticed or said anything about, made the preceding five years of unsuccessful, failed writing worth all the effort. They are two of the best moments of my life. By which I mean my whole life. (71)

Holy shit! His first daughter is five weeks old, and yet two of the best moments of his life are when he's writing in his office. He uses the same language here as he used to describe falling in love with Linda and Vanja, everything was possible, a state of rapture, the world saturated with meaning. Let me propose, then, that Linda and Vanja serve as mere training for the true love story: Karl Ove is a man in love with writing.

Indeed, if vol. 1 was an anti-bildungsroman, a refusal of adulthood, a rejection of society, vol. 2 is, emphatically, a künstlerroman, the story of how Karl Ove came to write My Struggle. And it's the story of a strange parataxis, the move, which he repeats, from Linda to writing. Right at the end, facing their troubled marriage, Knausgaard writes that Linda "had realized we would have to do something to break the vicious circle we were in, I agreed, it couldn't go on, it couldn't, we had to find a way out and strike a new path" (582).

The very next sentence? "At half past eleven I went into the bedroom and switched on my computer, opened a new document, and began to write" (582). And what does he begin to write? What is the text we see beginning to take form in these final pages? My Struggle.

Feeling grateful, this morning, to be in this with all of you—

Dan

ALSO IN THIS SERIES:

The Slow Burn, v.2: An Introduction

My Struggle, vol. 1: Cecily, June 6

My Struggle, vol. 1: Diana, June 9

My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

My Struggle, vol. 1: Dan, June 17

My Struggle, vol. 2: Omari, June 24

My Struggle, vol. 2: Cecily, July 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Sarah Chihaya, July 5

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

My Struggle, vol. 2: Diana, July 16

My Struggle, vol. 2: Jess Arndt, July 18

My Struggle, vol. 3: Omari, July 25

My Struggle, vol. 3: Ari M. Brostoff, August 1

My Struggle, vol. 3: Dan, August 4

My Struggle, vol. 3: Jacob Brogan, August 8

My Struggle, vol. 3: Diana, August 12

My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25

My Struggle, vol. 4: Omari, September 1

My Struggle, vol. 4: Dan, September 2

My Struggle, vol. 4: Diana, September 15

My Struggle, vol. 5: Omari, September 27

My Struggle, vol. 5: Diana, October 3

My Struggle, vol. 5: Dan, October 13