My Struggle, vol. 3: Omari, July 25

Philadelphia, PA

Dear everyone,

I've had a difficult time writing this letter.

My process thus far has involved reading all of your beautiful letters that have come before mine and thinking alongside all of you while I cull together every note and every fragment of a thought I had while moving through Knausgaard's world. In my own letters, I've been flippant, irreverent, humbled, and serious over these past few months as I've looked up the Swedish word for cinnamon roll and cringed at my own thoughts on masturbation. But, like I said towards the end of my last letter, there was so much that was keeping me from actually opening up to K in the way that I knew he wanted me to.

This time, as I read this third volume of My Struggle, centered around K's childhood from about the age of 6 until he begins what we would call high school as he grows up in a town on the Southern coast of Norway, what has haunted me most has been Dan and Jess's thoughts on the body, my own black childhood, and sideways thoughts on being a father in the sort-of-distant future (a life is only so long that seemingly even the most distant of life decisions can only be sort-of-distant). Many have asked how and why I became a part of this project and what I haven't said out loud is that I wanted to come to Karl Ove Knausgaard and figure out what this Scandanavian man who thinks he's Proust could say to me while I live through one of the most difficult racial times that I have seen in my adult life. And, though it may seem like a contradiction (and it is), I also wanted to write about literature that doesn't have profound implications on the way that I live my life now. I can't teach Harriet Jacobs or write about James Weldon Johnson without noting the ways in which even the oldest works of African American literature continue to have very real things to say about how I do (and, by extension, how my own theoretical future offspring will) operate on a quotidian basis. In essence, I wanted to have the same kinds of light conversations I had after I finished reading Ben Lerner's Leaving the Atocha Station on a whim two years ago, focusing on the protagonist's interesting relationship to foreign language in a foreign land rather than commenting on his profoundly arrested development (a decidedly upper-class white privilege) as would be my usual wont.

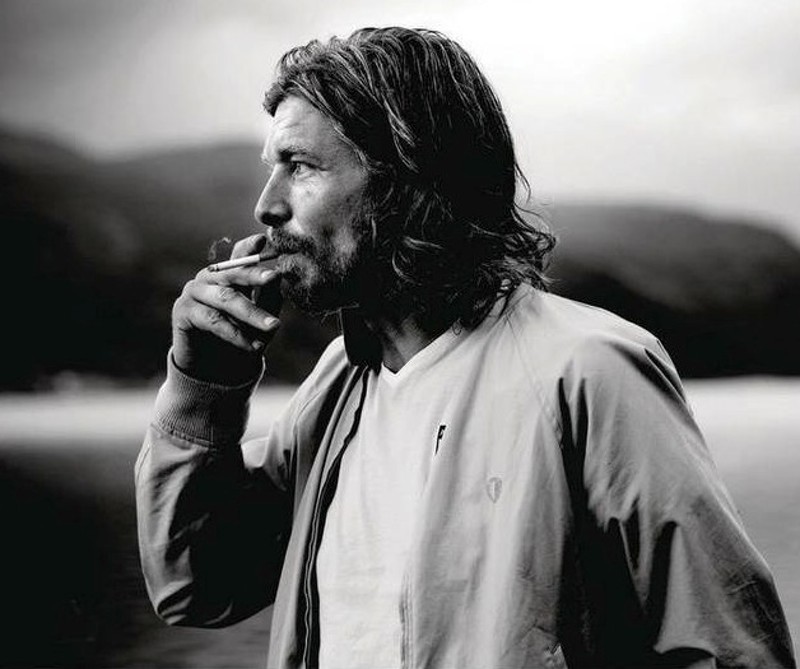

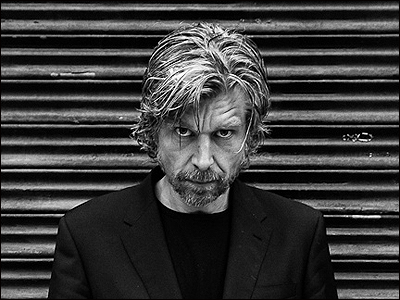

Both Dan and Jess spoke about the body that's off, the bodies that cannot be properly folded into whatever it is that "body" signifies. For all intents and purposes K is the antithesis of the antithetical body; he is the body. Given his rugged looks and a chiseled face, a good friend tweeted to me that K looks like Steven Tyler on the covers of Book 1 and Book 2. We can talk about straight cis white male privilege (and no matter what I say I can only effusively agree with Diana when she says K is every white guy in grad school who thinks that Kant speaks for the Human) but reading about K as a child growing up in Norway finally puts all of his neuroses and unpleasant behaviors into perspective. What's funny is that I think he thinks we all understood that he was coming from a different place back in Book 1 when it took over 100 pages to move beer from the base of a tree in the snow to an underwhelming and anticlimactic New Years party. Because of course who wouldn't hate a father who would punish their child for underage drinking and wasn't imaginative enough to go along with his 7 year old son when he says he saw a face in the sea on television...

K had a fucked up childhood, not the most fucked up childhood, but one that begins to change the parameters for how I'm used to seeing white guys in this kind of novel—that is, full of personality quirks that come out of nowhere. It's only now that I have seen the relentlessness of K's fear and pain as a child that I begin to see resonances between him and myself, not because we had similar upbringings but because I've often thought about what it would mean to raise children who, for reasons that go beyond anything I can do for them, will grow up in a world that they would be right to be frightened of as it would be frightened of them.I didn't see what he was so afraid of then but I feel for him now.

K sets up this novel by distancing himself from his own history, setting the groundwork for new loves, new stories, and new attachments to a childhood towards which he clearly has an ambivalence. In the beginning of the third book of an autobiographical enterprise called My Struggle, readers encounter third-person narration ("The [bus] door opened and out stepped a little family. The father, a tall, slim man in a white shirt and light polyester trousers, was carrying two suitcases" [3]) and another dizzying display of both the central importance and undependability of memory:

Memory is not a reliable quantity in life. And it isn't for the simple reason that memory doesn't prioritize the truth. It is never the demand for truth that determines whether memory recalls an action accurately or not. It is self-interest that does. Memory is pragmatic, it is sly and artful, but not in any hostile or malicious way; on the contrary, it does everything it can to keep its host satisfied. Something pushes a memory into the great void of oblivion, something distorts it beyond recognition, something misunderstands it totally, something and this something is as good as nothing, recalls it with sharpness, clarity, and accuracy. That which is remembered accurately is never given to you to determine. (11)

I originally wanted to write to you all about the radical difference between this passage and the novel's ending where the family moves to another town and K and his memory sit in the back of the bus, Memory in her wedding dress, K wondering what the next step is ("Little did I know then that every detail of this landscape, and every single person living in it, would forever be lodged in my memory with a ring as true as perfect pitch" [451]).

But, Memory is its own character in My Struggle, the ghostwriter that may not get credit in the byline but asserts itself headily as it figures out how best to contribute. My previous hang ups about K's inconsistencies regarding the work and reality of memory melted away as I realized that narrative memory and actual memory are two very distinct things and both are at play in this set of novels. They both act independently of Karl Ove's wishes in order to produce a story about the making and unmaking of worlds that occur in every childhood.

And so this is a story about baby's first porno magazine. This is a story about saving all of your shits for one culminating (e)sc(h)atalogical event. This is a story about not one but two different girls deciding you're too weird for like totally serious middle school dating. This is a story about a beetle in a bottle biting your willy. This is a story about juice boxes. This is a story about having a sick mother but being more interested in saving the dying cat you've had for a few days. This is a story about realizing that your mother "was the one who supplied the bandage when we had fallen and grazed our knees" but having "no memories of her reading to me and I can't remember her putting a single bandage on my knees" (259).

Most of all, however, this is a story about dealing with the pain of having any sort of proximate relationship with your dad, a man who can keep his emotions in check only slightly better than a child who cries when the wind blows incorrectly (i.e., all the time). The hazily and hastily sketched out alcoholic, hoarding father of Book 1 takes center stage in Book 3 and even though I don't know him any better now than I did then, I can at least now better appreciate the tortured relationship that he cultivated between himself and his two boys. He stands tall as an ever-present absence, quickly absconding into the safety of his study or his bedroom when he doesn't have to cook dinner or randomly take a child to the store.

Maybe this is what fatherhood is. A violent malaise of forced attachment that plays out in spurts and unpredictable moods. K gives readers just enough to despise his father, retroactively validating the iciness towards his death in the first book, while he also subtly humanizes a man that doesn't actually need to be liked. Perhaps we would be content with the evil father figure. Perhaps we want to blame any of K's foolish and unsavory character traits as an adult on an upbringing clouded in fear and mistrust. Certainly much of that is there but Memory refuses to let K mischaracterize a boyhood that is full of whimsy and adventure by overplaying the hand of the father that has been dealt to him.And so this is where I realize that I still can't properly relate to Karl Ove Knausgaard. It only has slightly less to do with my race or the things that I'm going through in the current moment than I previously thought. I wasn't playing in garbage dumps when I was a kid. I don't remember having a crush on a girl or even really thinking about girls in that way until I was in middle school and I certainly didn't feel them up underneath their sweaters in the middle of the day. I wasn't afraid of my father even if I respected him a great deal. But, there's something about this child's proximity to pain and fear that directly relates to my own thinking about becoming a father (a twist in the plot of my life that I won't be ready for anytime soon). After shifting from third-person to first-person in the novel's first pages, K keeps to the past with a more sustained fidelity than in his previous novels. But, one particular reflection from the present stood out to me:

I am alive, I have my own children, and with them I have tried to achieve only one aim: that they shouldn't be afraid of their father. They aren't. I know that. When I enter a room, they don't cringe, they don't look down at the floor, they don't dart off as soon as they glimpse an opportunity, no, if they look at me, it is not a look of indifference, and if there is anyone I am happy to be ignored by it's them. If there is anyone I am happy to be taken for granted by, it's them. And should they have completely forgotten I was there when they turn forty themselves, I will thank them and take a bow and accept the bouquets. (260)

I can give this to my future children. I can give them the space to love me and cherish me and forget me and feel safe with me. But, no matter how hard I try, I won't be able to provide the same kind of safety for my own children that K can provide for his or that he himself felt in Norway in the 1970's. They will have the playful moments that charmed me immensely in this novel like when K puts on his ugliest clothes to protest a female friend's sudden lack of desire to hang out with him. My own children will look like me and, like K, I don't want their pain to come from me. But this doesn't mean that they will have nothing to fear.

And perhaps this is what I felt the most.

Love and light,

Omari

The Slow Burn, v.2: An Introduction

My Struggle, vol. 1: Cecily, June 6

My Struggle, vol. 1: Diana, June 9

My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, June 17

My Struggle, vol. 2: Omari, June 24

My Struggle, vol. 2: Cecily, July 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Sarah Chihaya, July 5

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

My Struggle, vol. 2: Diana, July 16

My Struggle, vol. 2: Jess Arndt, July 18

My Struggle, vol. 3: Ari Brostoff, August 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, August 4

My Struggle, vol. 3: Jacob Brogan, August 8

My Struggle, vol. 3: Diana, August 12

My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25

My Struggle, vol. 4: Omari, September 1

My Struggle, vol. 4: Dan, September 2