My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25 (Guest Post)

Brooklyn, NY

Dear Cecily, Dan, Diana, and Omari,

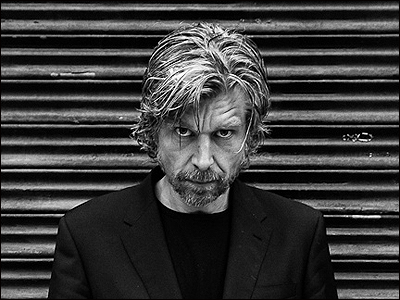

There are plenty of male writers I can't abide, but Karl Ove Knausgaard isn't one of them. I am open to K.O. (as his father and I call him), not because he is a man or not a man, good enough or not good enough, in love with his family or in love with writing, but simply because he is trying to be honest about his many "real mes" (301). We might disagree about the cultural value of this honesty, or even the honesty of this honesty, but after almost 2,000 pages, I don't think we can deny the effort.

Building on the memory work of Book 3, Book 4 is the only volume of My Struggle that clearly centers on a single year of Karl Ove's life, and I don't think it's a coincidence that he's eighteen, on a gap year teaching in Northern Norway, in a starkly contrasting culture and landscape to the ones he's known his entire life. I spent the last academic year in the East Village, my first stint in New York in more than a decade, and I know I'll always be able to locate 2015-2016 in the blue back-splash of my sublet and the half-hour ice cream lines of Van Leeuwen's. Unless you move every year, and sometimes even then, a year in a new locale stands out in memory, bracketed, because the mind gets to store all the memories of it in that very particular, vanished place. The moving mountains of Hafjord for Karl Ove and the constant construction of Cooper Square for me: both of them Brigadoons.

Age eighteen is another kind of Brigadoon, a transition point to adulthood for most western kids, often longed for, then lived intensely, and once it is over, never recovered. Except, of course, in documents and writing. Knausgaard kept journals during this period, but he burned them in his Bergen years, if we believe him in Book 5. Nevertheless, as he has claimed in countless interviews, his memory gets to work when he writes. He uses it fictively, coloring scenes he both remembers and does not remember, and in this volume of year eighteen, those scenes are as vivid and as conventionally dramatic as any in the whole of My Struggle.

I recently uncovered my journals from the same period, and it turns out my inner life in my late teens was uncomfortably similar to that of our kunstler. Like Karl Ove, I cared mostly about getting laid and having fun (the word "chill" was used frequently as a verb), and one day becoming a significant writer. Like K.O., I wrote painfully overconfident fiction and detailed accounts of mundane family activities. I even lusted in the same way as K.O.: I wanted traditionally beautiful boys in the same consuming, appraising way he wants traditionally beautiful girls. At the same time, I was anti-establishment, and pretended not to want traditional beauties at all. I cried regularly and tried to hide it, was alternately delighted and mortified by my body, and would never, ever in a million years want anyone, especially a beautiful boy, to catch me in a moment of weakness. In high school, I had many friends, yet I was voted biggest ego, a snub that hurt me deeply and that I could never admit to others. I was dutiful to my parents and grandparents but didn't understand, or frankly care about, their problems. And there were many periods, particularly at my establishment-making college, when I wanted to be drunk and wild and free all the time. If Karl Ove's struggle is a crisis of masculinity, then it's only fair to say that mine was, too.

As critics, we know better than to praise book simply because it reflects or illuminates a personal experience. It might be a reason to recommend it to a similarly inclined reader, or to call it a personal favorite, but to overlook its formal or political shortcomings merely because it speaks to us in some partial, and surely exaggerated way? This is the definition of lazy reading.

Or is it? After all, part of the Knausgaard sensation—which, we have to remember, was initially a surprise—is not only the drama he makes of the mundane, but also the vast attention he has achieved with a very particular set of personal details. Diaper-changing and meal-making aside, the particulars of K.O.'s life are so particular—to Southern Norway and Sweden, to the literary life, to coming of age in the 1980s, to parenting in the 2000s, to the shame of familial alcoholism—that it's a wonder anyone who is not a male Scandinavian writer born in the late 20th century to middle-class drinker-hoarders could understand.Yet many, many readers do. As Jess so deftly points out, there's plenty about the body experience and self-assembly to satisfy any seminar (or Slow Burn!) without a single nod to the "universal"—which, by the way, is a word I associate with Knausgaard criticism, but not with Karl Ove. Character and author will both claim "daily life," and even "life," but I think they're both much more interested in the particularities of perspective and ideology, and in the particular itself.

Rereading my journals, I found myself back in my own particular, eighteen-year-old suburban Maryland headspace, defensive about my choices and deficits, proud of my hasty poems, and angry with all sorts of people I'm no longer angry with at all. At the same time, I felt embarrassed for my privileged eighteen-year-old self, who was blind about so much—in herself, in the world—yet so sure of herself in her clumsy writing and, presumably, in her life. I lost at least a day this summer, worrying about that girl, wanting, on the one hand, to erase her, and, on the other hand, to protect her—the last two things she ever would've wanted from me. What she wanted was affirmation. She was writing her life to impress me, her older self, whom she clearly expected to be worth her time.

Rereading Book 4 has been much the same experience. It isn't a diary, but it might as well be, so naked is its self-involvement. Karl Ove's hedonism at russ, the month-long orgy of booze that apparently precedes all high school graduation exams in Norway, involves collective vomiting, careless encounters with dead or sleeping vagrants, and excessive property damage to his own mother's house. But for the defensive K.O., it is a rite of passage and a necessary exercise of freedom: "What a life. Going here, there, and everywhere, having a drink, sleeping whenever an opportunity offered itself, eating something maybe and then just carrying on. I came closer to being the person I really was and dared to do what I really wanted to do. There were no limits" (318). Later, in Hafjord, he devotes himself to his fantasy of the writing life. "It was much easier to write than I'd thought," K.O. tells his teaching colleague Nils Erik over drinks. "It's the first short story I've ever written. I'd written things in papers and that sort of thing before, but that's different. That was sort of why I came up here. I just wanted to try and write a book. And then I began and well...yes, all I had to do was write. It wasn't difficult at all" (104-5).

No doubt this Karl Ove, who also phones it in as a teacher and broods over every female in town, was an insufferable self for the adult Knausgaard to reencounter, as painful, in some ways, as his forty-something father, whom he meets again in his notebooks. "Here he stands before me as he was, in mid-life," Knausgaard writes on reviewing his father's terse chronicle of alcohol, emotion, family, and work, "and perhaps that is why reading them is so painful for me, he wasn't only much more than my feelings for him but infinitely more, a complete and living person in the midst of his life" (289). Jess is right that almost nothing we quote sounds like Knausgaard, because his writing works the way a whole body works, but this cellular bit, about his dad's life, comes pretty darn close.

So does the whole of Book 4. In this volume, the man in relentless pursuit of honesty stands before us as a living teenaged person: a precocious snob, a privileged butthead, and a child of alcoholism trying and failing to hide his wounds. He is also, significantly, already a writer of (bad) autobiographical fiction, an Easter Egg for any reader who's liked him enough to read thus far.

As for Dan's necessary question—"are we supposed to like him?"—maybe it's Knausgaard's great trick (or joke) to hate his many Karl Oves more than any reader ever could. Even if it's not a trick, I think it's the right move for this novel of extreme dilation. No one in my entire life, Knausgaard tell us on page after page, not my parents, not my children, not my critics, not my friends, not even the non-meatball eating future, can punish me more than me.Thanks for the Slow Burn, guys, and thanks for letting me chill with you all.

Yours in shame,

Katherine

ALSO IN THIS SERIES:

The Slow Burn, v.2: An Introduction

My Struggle, vol. 1: Cecily, June 6

My Struggle, vol. 1: Diana, June 9

My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

My Struggle, vol. 1: Dan, June 17

My Struggle, vol. 2: Omari, June 24

My Struggle, vol. 2: Cecily, July 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Sarah Chihaya, July 5

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

My Struggle, vol. 2: Diana, July 16

My Struggle, vol. 2: Jess Arndt, July 18

My Struggle, vol. 3: Omari, July 25

My Struggle, vol. 3: Ari M. Brostoff, August 1

My Struggle, vol. 3: Dan, August 4

My Struggle, vol. 3: Jacob Brogan, August 8

My Struggle, vol. 3: Diana, August 12

My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25

My Struggle, vol. 4: Omari, September 1

My Struggle, vol. 4: Dan, September 2

My Struggle, vol. 4: Diana, September 15

My Struggle, vol. 5: Omari, September 27

My Struggle, vol. 5: Diana, October 3

My Struggle, vol. 5: Dan, October 13