My Struggle, vol. 2: Jess Arndt, July 18 (Guest Post)

Nantucket, MA

Hey all,

So glad to join you (even if briefly). It's been fun and strange to careen headfirst into this series of letters, and I wish I had more time with them and you. Unfortunately, I'm late on top of late to this, coming to you full of the vertigo inherent in putting together the final edits on my own (very short) first collection of stories, and the irony isn't lost on me here that my 117 pages have taken so long to get together while I try to re-read book 2's expanse, a book I loved in 2014—a summer that I was also falling deeply in love—and before I knew a book of mine would ever be in the world.

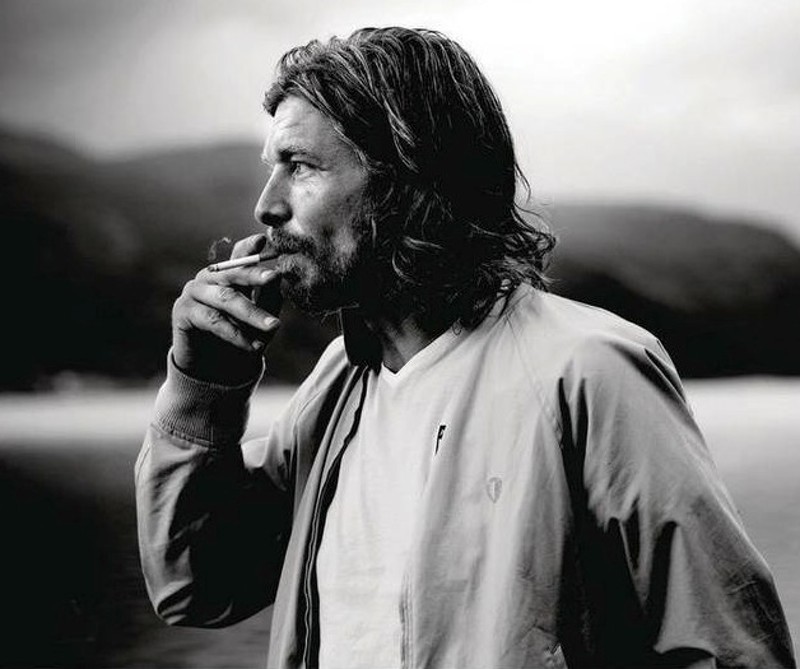

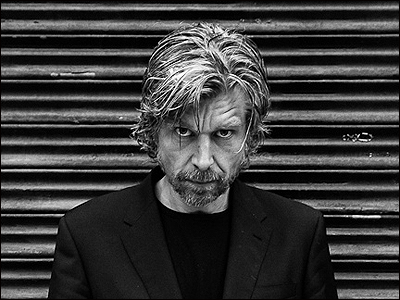

Man in Love.

To say I loved/am still loving reading Knausgaard is a somewhat intimidating position to take amidst what you have so far assembled here.

Book 2 is also, of the five so far translated to English, the book that was/is hardest for me to inhabit. As a female-born person with a motley or nonconforming gender, the itchy quest of how to fully enter spaces/bodies/texts takes up most of my emotional and creative time. I'm no stranger to the "lighter-opening-beer" paralysis so well-documented by Diana, or in general, the hyper-neurotic, often internalized study of masculine practice that consumes much of these books; in fact, even as someone for whom "passing as male" isn't an all-the-time identity goal, I spend much of my energy wading through masculinity's codes and signals, often (not entirely unlike Knausgaard), silently.

It's a daily occurrence for me to lower my voice, stick my chest out, and fold my shoulders broader when I enter men's bathrooms (that now feel much safer to me than women's). Conversely, yesterday I was stopped for speeding by a NY state trooper and as fear coiled through our car, I was aware of pulling my body smaller, making my voice less threatening to cool his response.

Perhaps, as my girlfriend pointed out earlier today, this is part of what makes Knausgaard's books so specifically fascinating to me: the assembling and disassembling of maleness, the inescapable fact (when reading) of being pressed into a porous and damaged male body—damaged as in not able to always perform as "cohesive" or "whole."

(Damaged also in another, not wholly disentangled way—from his father's psycho-emotional blows.)

I also wear a damaged male body.

Dan asks about this in his most recent letter, ie—"are we—a naïve question though I mean it—supposed to relate? Has this been, collectively, our tacit struggle?"

My girlfriend asked me an important question today too: "would you read this book with a class of non-white students?"

*

In re-approaching book 2, I've continued to wonder about why I feel closer to the other books in the series than this one. And, while, like some of you, I also paused (held him at arm's length) at his fury over his perceived loss of sexual potency during Rhythm Time class, and experienced discomfort during his disappearance into writing when fatherhood struck—if I'm honest, I think my distance from book 2 is more a response to the fact that "Man in Love" shows a Knausgaard who is mostly more assembled, or at least, more covered over, than not.

Where, in book 2, are the volcanic and multiple adolescences of books 1, 3, 4 and 5?

Maybe the plastic-bottled pit that ended the first book demanded he pan as far away from that boiling rawness as his biography allowed, thereby padding our next encounter with a new wife and three (as-yet unknown to us) kids? In any case, no matter how much he tells us about every possible thing, he doesn't reveal why or how he arcs and jumps as he does narratively—why book 2 follows book 1. Those particular maps remain his.

*

Re-reading "Man in Love," I dove straight for the scene where he cuts his face to pieces when Linda rejects him for Arve. "Long before I woke I knew something terrible had taken place" (198).

Do I love these molten passages of My Struggle, the especially shame-drenched parts, because of that now mostly-tired idea that queers live a second puberty? Or even, when coming into a new gender/s, a third or a fourth?

Am I relating? (Etymology: "bear(ing) back" to self?) Or I am doing something more complicated, perhaps a kind of co-writing or re-coding, based in part on what feels like a shared feeling, that I may not have a self at all?Knausgaard's body is everywhere in the books, lets me enter it at its best and mostly worst. Is it wrong that I take real pleasure in his anxieties around sexual performance? That I compare my own perceived inadequacies and labors with his? Join him? Then leave him, bolstered by whatever he's chosen to highlight or reveal, think "oh it's not so bad," for instance, I at least have dick that stays hard even if I come too fast? Etcetera etcetera.

Am I ever going to grow up?

*

It's hard having a body. Harder, as Dan writes, to have a body not like Knausgaard's, a body that gets killed for a taillight, or the speeding stop I survived.

But it is also hard to have Knausgaard's body. Trauma, and its uncomfortably close cousin, disassociation, never seem far. Read this way, his narrative cuts and loops seem less like carefully crafted attempts at cohesive or all-encompassing truths and more like expressions of bodily surges, or hot circuits.

"Interesting!" [Geir] said. "You turn everything inward. All the pain, aggression, all the emotions, all the shame, everything. Inward. You hurt yourself, not anyone else out there" (202).

I quote this in part because it follows one of the two most electric sections in book 2 (his face cutting and then—I agree Cecily!—Linda giving birth) but also because, by this point in my letter, I have begun to feel anxious about my lack of quotes, from Knausgaard or otherwise.

But something strange happened while reading each of you. Whenever I came to a Knausgaard quote, I thought, almost dismissively, "oh, but that doesn't sound like him." His writing works as a kinetic whole, but no piece stands on its own, either emotionally or as a platform for what he "thinks" of everything. It's like asking a skin cell to report accurately on the body.

Another way of thinking about it: when you disconnect the present churn from the already-churning and still-to-be-churned, you get a kind of static, energy-less or flat wave. And maybe because I am writing to you now from an island, where sea is smashing everywhere, I can't help thinking about something I read yesterday about killer whales in captivity—that when in tanks, their giant, usually-stiff fin is always curled down.

Trauma in the body, trauma as form, trauma shaping, imprinting, sticking in cells.

Nonetheless, right after he cuts his face, an act not of disassociation, but at least partially of, I'm guessing, tying his feelings to his body, the text jumps forward and he is meeting Linda and Geir in Stockholm for a play:

Into it disappeared plot and space, what was left was emotion, and it was stark, you were looking right into the essence of human existence, the very nucleus of life, and thus you found yourself in a place where it no longer mattered what was actually happening. Wasn't there an enormous red sun shining at the back of the stage? Wasn't that Oslvald rolling naked across the stage? I'm not sure anymore what I saw, the details disappeared in the state they evoked, which was one of total presence, burning hot and ice cold at once.

And then just a page later:

After we parted company and I was trudging up the hills to my rented room in Mariaberget I realized two things.

The first was that I wanted to see her again as soon as possible.

The second was that that was where I had to go, to what I had seen that evening. Nothing else was good enough, nothing else did it. That was where I had to go, to the essence, to the inner core of human existence. If it took forty years, so be it, it took forty years. But I should never lose sight of it, never forget it, that was where I was going.

There, there, there.

As a white American with female stamped on my driver's license, who wears a silicone dick to have sex, and takes herbs to enhance testosterone, I am not necessarily supposed to relate to Knausgaard's body, but maybe that's exactly how I do. As he says—the details disappear into the state they evoke. A state that always seems, at least to me, to be reaching for presence.

To answer my girlfriend's question then, at least how I am thinking today:would I explore this body experience, about trauma and the perhaps impossibility of assembling (ever) a cohesive self, of coming fully into presence, with a class of non-white students and female students and refugee students (and whoever else Knausgaard is not explicitly addressing)...

...think about the spasms and crying and blackouts and wanting to be good and what good even means, who and what conditions create that want...

...hear what they might have to say?

Yes.

Yours,

Jess

The Slow Burn, v.2: An Introduction

My Struggle, vol. 1: Cecily, June 6

My Struggle, vol. 1: Diana, June 9

My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, June 17

My Struggle, vol. 2: Omari, June 24

My Struggle, vol. 2: Cecily, July 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Sarah Chihaya, July 5

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

My Struggle, vol. 2: Diana, July 16

My Struggle, vol. 3: Omari, July 25

My Struggle, vol. 3: Ari M. Brostoff, August 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, August 4

My Struggle, vol. 3: Jacob Brogan, August 8

My Struggle, vol. 3: Diana, August 12

My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25

My Struggle, vol. 4: Omari, September 1

My Struggle, vol. 4: Dan, September 2