My Struggle, vol. 5: Omari, September 27

Portland, Oregon

Dear all,

I know what you want me to write about. However, I'm going to defy expectations. It's like when K writes that poem that consists of one word that begins with C and rhymes with bunt. It's as if I've taken my typewriter and written a similar word that begins with C and rhymes with sock 352 times (I counted) but when it comes to reading that poem in front of people I admire and distrust, I just can't do it. (See my postscript.) All of my letters about tarrying in the filth and "choking the chicken" have somewhat predictably led us to this fifth book in My Struggle where K ages out of adolescence and more properly becomes an adult who can freely have sex and must negotiate this weird tension between being a writer and being an asshole. I ended my first letter by asking K why he doesn't masturbate and here, finally, we get to see K do the solitary deed. But, if I write a whole letter about this episode, I'm going to look like I'm obsessed. Much like what K says about that poem, further thoughts about his habits belong in my room where I am alone, not here where I am with other people.

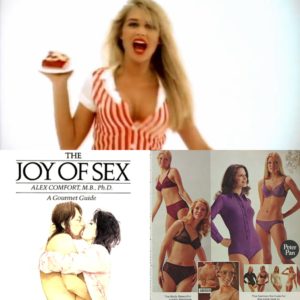

I will say this one thing though. I instantly became uninterested in K's masturbatory orgasm when I finally got to see it. It was so pedestrian that even though I wrote "Finally!" in the margins (exclamation point and all), I pretty much instantly forgot about the act itself. Sure, there was a bit of drama, what with it taking place in a public-ish bathroom after seemingly a wealth of knowledge about onanism was handed down to him by way of boyish jokes and witty, youthful banter. But, who hasn't heard the tale of the boy taking a coffee table book of what I can only imagine are artistic and tasteful nudes to the bathroom for an Event that awakens his sexual self? If it wasn't this particular object of cultural refinement, it would have been The Joy of Sex, Warrant's "Cherry Pie" video, or a Sears catalog. We all have such a story and to see it again absent any panache or novelty made me question what I was expecting when I got to page 97.

Take your pick.

What did flash up in my memory after I read this scene, let out a deep sigh (nope), lit my cigarette (negative), and dragged my comforter back up to my bare shoulders (fully clothed at a comfortable temperature) was the only interview of K that I've allowed myself to read since we began this project. I've been trying not to let Knausgaard the writer and his public persona influence my reading of K the character and his incessant whining. But, when an interview between Karl Ove and James Wood published in the Winter 2014 issue of The Paris Review found itself on my Twitter feed of refined cultural taste, I couldn't help myself. After admitting that he had no problem with the flat characterization and outright objectification of female characters in his novel because that's just how some men look at women (no feminist argument here...), Wood responded in what I would consider to be a shocking fashion:

It's one strength of your writing that you risk that kind of statement—or really, that kind of enactment or confession. It is a risk—the risk of people thinking all sorts of things about you, including maybe wanting to have sex with you [laughter].

I read this and spit out my coffee. The last thing I saw K as was a sex object. Yes, maybe that reveals something about myself after a number of letters that wondered aloud about why K refused to participate in a solitary sexual act that we all regularly enjoy. However, I didn't speculate about K's relationship with his body so that I could eventually read him recalling when he lifelessly "wrapped [his] fingers around [his] dick and jerked it up and down" (97). I write a lot about what Audre Lorde calls the uses of the erotic. In an essay that uses that phrase as its title, Lorde describes the erotic as a kind of power, "used and unused, acknowledged or otherwise. The erotic is a resource within each of us that lies in a deeply female and spiritual plane, firmly rooted in the power of our unexpressed or unrecognized feeling" (53). For Lorde, there is possibility in sex. There is life in sex. There is community in sex. Contrastingly, for K, there is utility in sex. There is flushing the toilet in sex. There is guilt in sex. And this is why it is difficult to imagine K as a sex object. What is there to desire when desire feels so based in mere drive fulfillment? So akin to scratching a pervasive itch?Wood's comment feels so out of place because wanting to have sex with K seems beside the point when his relationship to the erotic so often has few stakes beyond a gratification of basic needs. It is not only my training in what Eve Sedgwick calls paranoid reading that leads me to such a conclusion. The combination of the proliferation of details in this genre of writing and K's active discouragement of reparative reading puts great emphasis on the base fact that, as humans, we often just need a good fuck, whether that be with someone else or with ourselves. This doesn't inherently make K an unsympathetic character or foreclose the possibility that the erotic can be life-affirming or spiritually resonant or community building but it does mean that I become suspicious of readings of K that make him seem sexy.

Now, I don't know why it's taken me five letters to come to Sedgwick, but let me back up a second and quote her at length here because this one excerpt from her essay, "Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, Or, You're So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay is About You," will now always resonate with me when I think of my often hostile treatment of K:

[To] read from a reparative position is to surrender the knowing, anxious paranoid determination that no horror, however apparently unthinkable, shall ever come to the reader as new; to a reparatively positioned reader, it can seem realistic and necessary to experience surprise. Because there can be terrible surprises, however, there can also be good ones. Hope, often a fracturing, even a traumatic thing to experience is among the fragments and part-objects she encounters or creates. Because the reader has room to realize that the future may be different from the present, it is also possible for her to entertain such profoundly painful, profoundly relieving, ethically crucial possibilities as that the past, in turn, could have happened differently from the ways it actually did.

I swore that I had made the switch from paranoia to reparation in Book 4. I allowed myself pleasure whereas I had mostly been trafficking in critique. I clung to the hope of possibility when K moved to Northern Norway and sidled away from a past that he found to be distressing and bitter. My original paranoia is actually what allowed the reparative to shine through; it's clear that Karl Ove Knausgaard, a prosperous father of four children who has been the subject of Paris Review interviews and the crafter of a novel that 12 out of every 10 Norwegian homes cherish in their literary collections, was going to get through his struggle and enter his relatively well-off present-future (our present, K the character's future). This foreknowledge of where K eventually ends up provides the space for being open to the more local futures that K imagines from his past, the futures that he wouldn't have seen while he was living in the moment. I asked many questions during K's journey. Will he ever get with Ingvild? How will he find success during this writing academy in Bergen? Does he get over his white wine problem? And I got reasonably satisfying answers to those questions, but the answer to my ultimate question came and went and was just as disappointing as the first time...

Will K ever actually surprise me? No. He won't.

This is why I'm frustrated with my continued frustrations with that scene of baby's first jerk off. Not once throughout My Struggle has K ever suggested that he wants to be Audre Lorde (and this now may be the most ridiculous sentence I've ever written). Lorde begins "The Uses of the Erotic" by naming the erotic as a deeply female resource because it needs to be. Throughout history, black women have had their sex used against them for the perpetuation of both white supremacy and black patriarchy. K doesn't need the erotic to do the work that Lorde needs it do. He's a white guy. There's no historical exploitation of white male bodies for their sex that requires a cultural renegotiation of the relationship between white men and the erotic. They don't need that power. But, it does beg the question: why linger in masturbation when this act could just be another line item to read distantly or, at least, without suspicion? K's answer is that sometimes there is no reason to. A penis is a penis is a penis. A jerk off is a jerk off is a jerk off.When K actively flattens out this primal scene that, for many boys, suggests a sexual maturity that K can only stagger around but never quite achieve, I immediately retreat back to the tired position of being disappointed with a man that I will never meet in real life. I wanted so much from K's first foray into happy endings that this future I could have seen a mile away yet again changed the way I read now. Distance it is moving forward. I don't have the space in my heart to be this crestfallen with a person that I will never meet. Book 6 will be a work of microsociology and I will finish this project by reading Karl Ove Knausgaard's petulant insecurities, non-feminist renderings of female life, flagrantly violent alcoholism, inability to empathize with even close relatives, and impeccable taste in music as a close but not deep consideration of Scandinavian culture.

You asked for it, Norway.

Oh, and I guess I lied. All I can ever talk about is K's relationship with his penis. C'est la vie.

Lovingly,

Omari

P.S. I admire and trust all of you.

ALSO IN THIS SERIES:

The Slow Burn, v.2: An Introduction

My Struggle, vol. 1: Cecily, June 6

My Struggle, vol. 1: Diana, June 9

My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

My Struggle, vol. 1: Dan, June 17

My Struggle, vol. 2: Omari, June 24

My Struggle, vol. 2: Cecily, July 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Sarah Chihaya, July 5

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

My Struggle, vol. 2: Diana, July 16

My Struggle, vol. 2: Jess Arndt, July 18

My Struggle, vol. 3: Omari, July 25

My Struggle, vol. 3: Ari M. Brostoff, August 1

My Struggle, vol. 3: Dan, August 4

My Struggle, vol. 3: Jacob Brogan, August 8

My Struggle, vol. 3: Diana, August 12

My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25

My Struggle, vol. 4: Omari, September 1

My Struggle, vol. 4: Dan, September 2

My Struggle, vol. 4: Diana, September 15

My Struggle, vol. 5: Omari, September 27

My Struggle, vol. 5: Diana, October 3

My Struggle, vol. 5: Dan, October 13