My Struggle, vol. 5: Diana, October 3

Brooklyn, NY

Dear you,

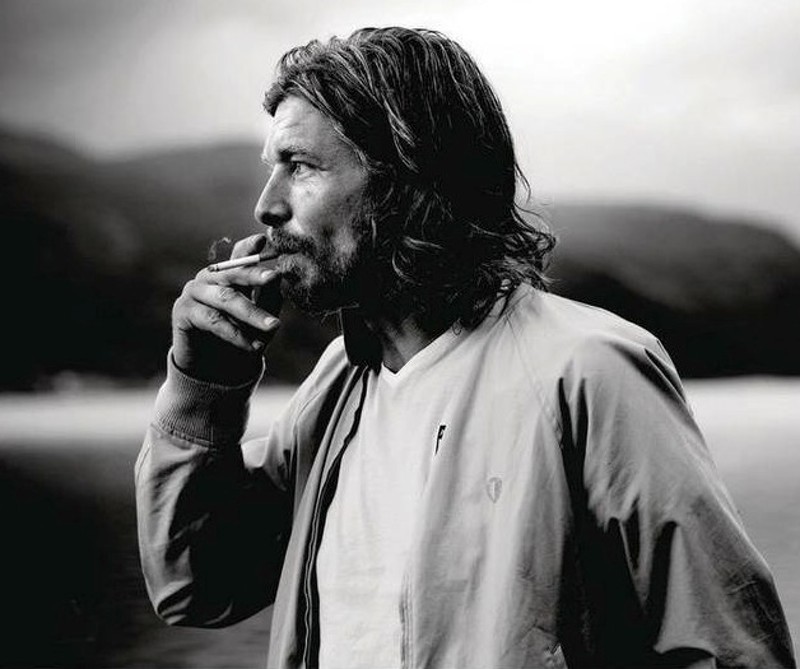

I think we're supposed to have wanted to have sex with K.'s eyes, given the book's branding? Like: it's not just that we're supposed to want to hold his hair in our hands while we share his stare; we're also supposed to find ourselves aroused by his way of looking.

I read that interview alongside your letter, Omari, and it's even funnier to me that James Wood's admission of desire to have sex with Knausgaard comes immediately after refusing to answer Knausgaard's question:

K.: Every time I see a woman, I think, How would it be to have sex with her? I think that's the first thought for every man. Don't you think that? I mean, if you are absolutely honest?

W: I didn't write the book. I don't have to answer the questions.

So Wood doesn't need to account for his imagination of sex with all passing women, but he's happy to wink at his desire to have sex with Knausgaard himself. I'm honestly confused.

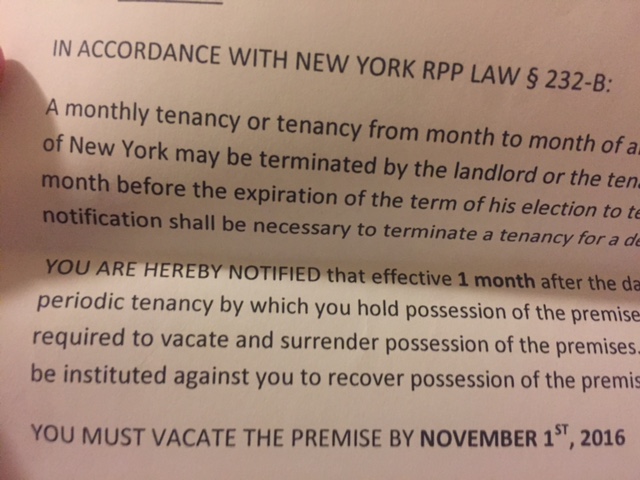

And I'm in a moment of repetition, being somewhat foggy-headed still from having learned Sunday night that I must vacate my apartment within 30 days. I mistook a memory of yours, Omari, for a memory of my own: I started to type that I spit out my coffee when I read that part of the interview, but I was on the R train when I read it, where I never drink coffee, and in fact, I couldn't have been surprised, as I was only reading the interview on account of your letter's allusion to it.

Dan informs me that, in my eviction, I'm repeating an experience of Karl Ove's from Volume 5:

At home there was a letter protruding from the door crack. I opened it. It was notice to move. Owing to renovations I would have to be out before the middle of December. Was that legal? (289)

I didn't find my letter under the door. Instead, my landlord handed me two envelopes himself, each with identical notifications. He said nothing but, "I'm sorry," as I read. "OK." I closed the door and cried on the floor, I guess. It wasn't just a matter of money, or the stress of looking for apartments in NYC, which, ugh, or even my general manner of being easily overwhelmed. I think it was realizing I'll have to stop cohabitating with my past: I felt very afraid that I had entrusted the walls and the arrangement of furniture to store a lot of the memories I don't have space for in my own feelings, and that if I moved out, I would either have to carry them myself or lose them altogether.

Perhaps this is how the fictional Karl Ove feels about these volumes: it's nice to create a storage unit for the bits of yourself you're not ready to throw out. At least, my brief encounters with the words of Knausgaard outside of the narration of his Karl Ove seem to affirm this: there's little in My Struggle he likes, save some brief essays on subjects of interest to him, like asides on Paul Celan. Perhaps Knausgaard doesn't need to like the books, if they're useful to K. Regardless, no Gunvor crawled into my bed with "the fullness of her breasts" to make up for the sadness of my apartment's loss, nor do I think the landlord imagined having sex with me, the way all men supposedly do, when I opened the door, nor did yet another Danish apartment fall into my lap, nor did I open this document, at that time, to imitate the impulse to spill over onto pages.

In the interview with Wood, Knausgaard repeats some of K.'s thoughts on the secondariness of fiction: "Poetry is the best medium, but if you can't write poetry, you do the second best."

I've always gotten prose-poetry mixed up, in my own work. Instead of prose aspiring to the dignity of poetry, via connotation's triumph over denotation or whatever else makes sentences seem more fey, I find myself stubbornly writing prose-in-line-breaks. It's relaxing when poems get a chance to flirt with prose's lack of neurosis, its willingness to say relatively direct things despite the fact that its author knows that, whoa, language constructs reality.Thank you, Omari, for giving me the chance to re-read Audre Lorde's "Uses of the Erotic."

I feel compelled to challenge myself, in advance, on the uses to which I'm tempted to put Lorde's essay: to hope, momentarily and wrongly, that I, as myself, could easily answer her call to "do that which is female and self-affirming in the face of a racist, patriarchal, and anti-erotic society" without risking a self-affirmation already supported by that same society; to note how her hard distinction between the erotic and the pornographic maps onto Gilles Deleuze's writing on masochism, given the strange recurrence of masochism's questions in our recent letters; to share the lines that made me sit still, eyes closed, wondering if there was a note to take other than the repetition of the line itself: "And there is, for me, no difference between writing a good poem and moving into sunlight against the body of a woman I love."

My favorite jealousy is the jealousy of feelings. If Karl Ove envies those who can write and read poetry, I truly envy Lorde's experience here of writing a good poem. And conversely: that a good poem is not hard to write, by this account; all you have to do is fall in love, a quite commonly realized impossibility (though I suppose some of us will find it easier to write the poem than others, depending on whether we fall in love with women in any light).

Instead of Knausgaard's rarefied sense that the poem is something that happens to a few good men only in the wake of war, the "good poem" here is an act of love between women.

The poet Helen Guri was visiting New York last week, and when she read at the poet Corina Copp's apartment, she read prose. Somehow, not all of us noticed, having thought instead that this incredible account of her residency at Al Purdy's house—where she commits herself to learning as little about Purdy as she possibly can during the duration of her stay, where she and her friends restage the photos of Purdy on the wall, where she finds her image in the mirror coming to resemble less of the femme, and more of the Purdy—was a fucking fantastic poem.

I don't think she liked this mistake. It's a peculiar annoyance to have people insist you're writing poems when you write entirely other things, just because they know you to have written poems before; something about the "poet" label follows you across genre in an especially puppy-like way. She says of Purdy's poems:

I don't like their misogyny or racism. Maybe this is because both my grandfathers died before I was born. I never had the chance to develop affection for old white men with tobacco breath and what they say when they're exhaling. I've never loved one.

When I started accidentally writing about Helen here, I was very nervous. Perhaps I'd had too much wine to remember the non-poem properly; perhaps one is always wrong to try to share the feeling of what was so loved in the moment of reading a friend. In her narrative of the writing residency, I realized, I couldn't remember whether Guri talked about what she was writing in Al Purdy's house. Of course, I then found the piece online, and looked for information about the poetry or prose she might have written, in addition to this piece, "Horseplay: Some Poses in Search of Love." Instead, I found poems like Lorde's: women, and even men, moving into and out of the light, as bodies (Guri concedes that "Purdy was a body" as much as she hoped to learn nothing of him), horseplay as its own writing, the purpose of a residency as the production of butchness and dance . . .

Omari, yours is the only letter since my last, and I'm drawing heavily on you; I hope you'll forgive this as an element of correspondence, where echoes show affection. K. makes secondhandedness prosaic; Lorde: "the erotic cannot be felt secondhand." This secondhanded feeling is something else, I guess.

I wish I had been more responsible, this summer, to letters, to reading, to you all. But instead,

Irresponsibly,

Diana

ALSO IN THIS SERIES: The Slow Burn, v.2: An Introduction

My Struggle, vol. 1: Cecily, June 6

My Struggle, vol. 1: Diana, June 9

My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

My Struggle, vol. 1: Dan, June 17

My Struggle, vol. 2: Omari, June 24

My Struggle, vol. 2: Cecily, July 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Sarah Chihaya, July 5

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

My Struggle, vol. 2: Diana, July 16

My Struggle, vol. 2: Jess Arndt, July 18

My Struggle, vol. 3: Omari, July 25

My Struggle, vol. 3: Ari M. Brostoff, August 1

My Struggle, vol. 3: Dan, August 4

My Struggle, vol. 3: Jacob Brogan, August 8

My Struggle, vol. 3: Diana, August 12

My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25

My Struggle, vol. 4: Omari, September 1

My Struggle, vol. 4: Dan, September 2

My Struggle, vol. 4: Diana, September 15

My Struggle, vol. 5: Omari, September 27

My Struggle, vol. 5: Diana, October 3

My Struggle, vol. 5: Dan, October 13