Issue 5: Formalism Unbound, Part 1

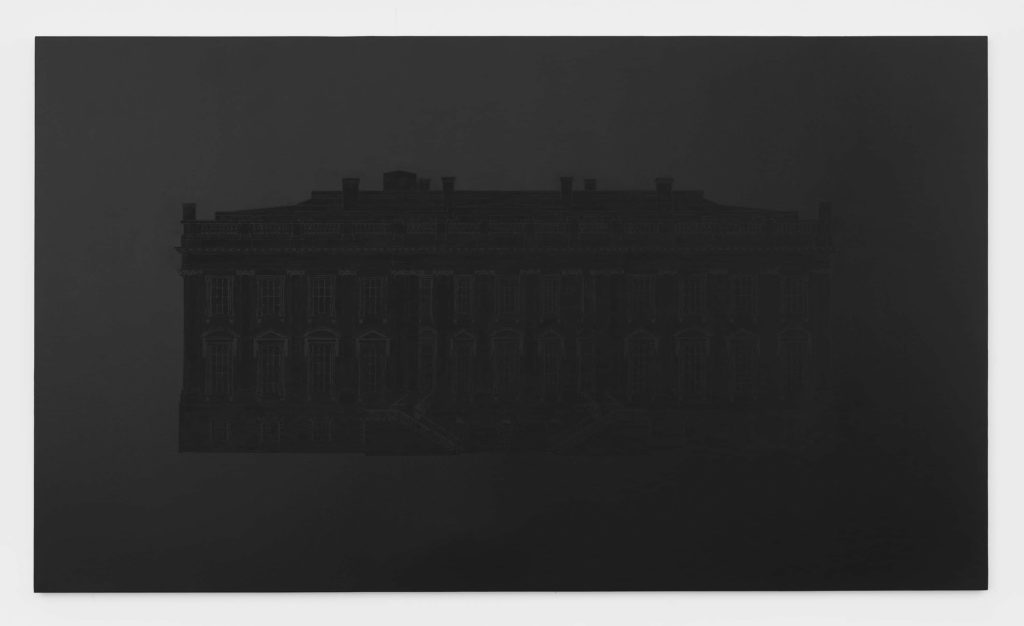

Twenty-eight fat televisions are stacked into a pyramid of sorts in the corner. In the darkened room, each screen plays the same short excerpt of Nina Simone's 1964 performance of "Black is the Color of My True Love's Hair." The sound and array of images from the performance flow on one continuous four-minute loop. Created in 2015, Paul Stephen Benjamin's "Black is the Color" meditates on what it is to think about blackness and form. I saw this piece in January 2019 as part of Pure, Very, New, a solo show curated by Lisa Freiman at the Marianne Boeksy Gallery in New York City.1 The show includes other meditations on and through blackness: a flag of stripes and stars assembled from different shades and textures of black cloth, a series of portraits of black men and boys also rendered in shades of black, the White House rendered in black. Here, I work through "Black is the Color" to reflect on the complex ways that black studies has positioned blackness in relation to form and desire. Thinking with "Black is the Color" also allows us to glimpse how we might use sensuality as methodology, producing a type of formalism to think blackness in black studies beyond its negotiations with desire.

First, negation. One strand of black studies, often positioned in relation to Afro-pessimism because of its interest in ontology, argues for thinking about blackness through the prism of negation, which is to say, blackness operates as the antithesis to the project of the human (and affiliated entities including gender, affect, and subjectivity).2 In Ontological Terror, Calvin Warren focuses on the non-relation between blackness and Being. For Warren, Black Being emerges as pure function, the antithesis of Being. Warren elaborates, "the function of black(ness) is to give form to a terrifying formlessness (nothing). Being claims function as its property (all functions rely on Being, according to this logic, for philosophical presentation), but the aim of black nihilism is to expose the unbridgeable rift between Being and function for blackness."3 Warren argues that continental philosophy's framing of the question of Being has elided the possibility of Black Being such that blackness exists contra to Being. This exclusion results in an anti-black dynamic that produces blackness as a being-for, a projected desire. In Warren's schema, blackness has no way to produce its own forms. Interpolated into the negative space others have designated for it, blackness can at best produce a mode of expressivity through catachresis: the activation of a dense mode of over-representation that cloaks, but cannot coalesce into its own form.

For many scholars, formlessness renders blackness a powerful disruptive ontological force. Stephen Best, Rizvana Bradley, and Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, for example, powerfully analyze how blackness interrupts the possibility of desire, and their work theorizes modalities of aesthetics and being that are specific to blackness.4 In working with blackness as alternate onto-epistemology, opacity makes explicit the difference between the operationalization of blackness and the version of blackness that refuses these projections. The most straightforward example of these dynamics is Benjamin's "Paint the White House Totally Black" (2017), which represents the White House in shades of black, leaving viewers to draw on their own understandings of blackness to make sense of its juxtaposition against the shape of the White House. Negation is implicit, but the value of blackness is not pinned down; the form that it takes is understood in relation to that of whiteness — the US presidency, apparatuses of state power, and those current and historical affiliations with white supremacy.

In "Black is the Color," however, the structure of negation is harder to parse because Benjamin plays less with external projections of blackness and more with the lived history of black Americans. The piece sits with the question of what black people can and have done, emphasizing action through both Benjamin's and Simone's choice of song. "Black is the Color of My True Love's Hair" was originally a Scottish ballad that made its way through Appalachia as a folk song, but Simone rearranged it and recorded it twice: first in 1955 and then in 1964 — the more famous version with piano and bass. In this context and through this remixing, the song became a black power anthem. Black is not merely a color (or negation), but a sign of resistance. Simone's proclamation of love reflects the slogan "black is beautiful" and acts as a rejoinder against racial hierarchies. The 1964 track was, in fact, recorded during the early part of Simone's tenure with the Phillips label, in the heat of the civil rights movement. This streamlined version highlights the emotion in Simone's voice, which makes her declaration not only plaintive, but a sign of resilience and protest. In a 2016 assessment of this era of Simone's work, Carvell Wallace describes the emotions that her voice stirs in the listener: "Nina Simone hurts you. She does it with her voice, which is sharpened and ready, versatile as a set of top flight chef's knives able to slice through the music making a myriad of purposeful and precise incisions, wounds, gashes, or lacerations."5

Here, we come to the idea of the virtual within black studies, which understands blackness as a communal set of references that exerts itself through an affective and political pull on the body. At the beginning of Afrofabulations, Tavia Nyong'o announces his intention to "diagram a virtual, tenseless blackness that shadows and camouflages the communicative apparatus that colonizes time."6 This argument for the virtual is distinct from one that adheres to thinking about blackness as a form of collective consciousness produced by a relationship to the transatlantic slave trade, and instead argues for thinking with a blackness that is ever emergent: a blackness that structures what is possible, visible, and representable. Kara Keeling's work on the impossibility of the black femme in The Witch's Flight, for example, exemplifies how to work with the virtual vis-à-vis blackness.7 In accounts of virtual blackness, too, we find desire, but this desire emanates from a project to make blackness into something. This virtual form of blackness allows us to link Simone and Benjamin to something that exceeds representation while also remaining anchored in the reality of some black people's experiences. These excesses circulate in the realm of the affective.

Beyond the event of Simone's resignification of the song, working with the virtual asks us to analyze the particulars of Benjamin's presentation of Simone — what transmits and how? In the piece, Benjamin traffics in nostalgia — the televisions are old, the song is from the 1960s — and he further manipulates the televisions by framing each image with a circular border. This visual device plays on the pull of the pastness and the pull of the moment of black power in the 1960s, but the sonic loop also comments on the relation between the past and the present. Instead of reproducing Simone's ode to love, Benjamin only permits the words "Black is a color" and a smattering of piano sounds before beginning the loop again. Working through the concept of the loop, Lauren Berlant suggests that it is a technology that highlights the minoritarian subject's particular interaction with forms of historicity — by being both "caught" in modes of projection and able to manipulate that form of stasis.8 This focus on the actions possible within constraint are emblematic of the possibilities that the virtual offers. When we think about the piece's 2015 context, we can see the loop in relation to Black Lives Matter, the protests that emerged against the perpetual horror of violence against black people, and the desire to assert value for black lives in an anti-black world. Through this lens, blackness circulates as a set of lived social relations. The virtual gives us a framework to decipher meanings of blackness that are not made explicit in the artwork, but which hover around what we think we know about the entanglement between Benjamin's and Simone's references to the collective plight of black people.

Thinking about blackness and collectivity, brings us toward the minor alteration that Benjamin makes to Simone's voice and song. She sings "black is the color," on the album, but in the installation she sings "black is a color," which Benjamin argues is a nod toward debates surrounding the black arts movement on the place of aesthetics and politics within art. Benjamin explains:

Some of my work is about the color black. It's a reference to the article "Black is a Color" that Raymond Saunders wrote in 1968 in response to Ishmael Reed's article about the state of black arts. He was interested in formal qualities as well as blackness being a part of art, but he said it shouldn't be the art. To put those things in art complicates it. In the song Nina Simone sings "black is the color." In Saunders's article, it's "black is a color." I altered her voice so that she says Saunders's version.

I've worked with this idea of black — the color black — for 8 to 10 years. It started with these collages and assemblages [points to wall]. I started doing work without the color black in it. I was looking for this idea of unity, so that when you are up close you see individual elements, but when you step back it's an abstraction.

I'm curious about the relationship of the color black and "blackness." What is its visual aspect, what does it sound like?9

By reflecting on these debates, Benjamin asks what it means to think about blackness in relation to questions of signification — does it exist in excess of these modes of projected desire, and if so, how can we decipher this mode of blackness? Is blackness always tethered to these external overdeterminations? Many scholars have offered a range of insights into the complexities of these central questions within black studies. I have focused on negation and the virtual to highlight two specific orientations toward the question of blackness: ontology and the social — although I am not invested in holding these up as entirely separate or even at odds with each other. What I want to highlight in this essay is the philosophical difficulty of specifying blackness.

Without definitively answering these questions, Benjamin's shift from "the" to "a" moves us into the sensuality of blackness in its invocation of multiplicity, inviting us to think with method (and formalism) instead of form. Working with the sensual, I argue, requires us first to move outside of the space that is dominated by desire. Desire, as I note elsewhere, is a problematic condition.10 It relies on recognition, which is often smuggled in via particular notions of subjectivity; access to which is not necessarily granted to those who are racialized and thereby deemed other and relegated to the realm of projection. Further, desire is the product of a subjectivity intent on possession. In Habeaus Viscus, Alexander Weheliye links the project of racialization to the same mechanisms as desire, arguing that desire is vital to the production and maintenance of racial hierarchies.11 Desire inhabits the virtual and haunts the ontological, but I would like to move beyond these dialectics toward pleasure. As such, I urge a theoretical movement toward sensuality and the flesh. Instead of making blackness transparent or specifiable, working with sensuality asks us to attend to our own embodiment and its enmeshments in circuits of history, capital, and power, so the question becomes not what is or is not blackness, but how does it register? I see this methodology explicitly in conversation with Denise Ferreira da Silva's discussion of a black feminist poetics that "attends to matter in the raw." For her, this means "steps towards a reflective practice that does not, for instance, approach a given artwork as a particular to be subsumed under a, even if subjective, (formal) principle organizing a common (universal sense)."12 For me, this reflexivity must be explicitly routed through and felt in the body; this is why sensuality matters. Further, if we are no longer trying to locate causation, we can linger in the effects on the body — perhaps finding pleasure in unexpected places. This excess of bodily pleasure which emerges from racialization — but always exceeds its capture — is what I term brown jouissance. In order to perceive it, sensuality. Or, more specifically, a sensual methodology, which I position as adjacent to formalism because of its emphasis on the surface and the flesh as perceiver.

Thinking with brown jouissance, we can return to the loop that plays without attempting to produce meaning from its presence, and instead attend to its embodied effects. As I write of other loops in Sensual Excess:

loops foreclose narratives of progress and focus on the plea-sures in dwelling on the unfinished. They also reorient the relationship between sensation and temporality. Rather than imagining that hyste-ria or perversion stop time, these bodily performances generate their own temporality, which is distinct from the conventionally narrativized time of progress in which there is a past-present-future. This is a tem-porality produced through the oscillation between subject and object.13

In this analysis we see that what is at stake in the loop is still a temporality of repetition, but this non-progress also entails staying in the space of the present and the possibility of pleasure in the song. This method allows us to stay with Simone's genius improvisation on the piano, which Joshua Chambers-Letson describes as "Improvising beyond the limits of genre, Nina Simone was producing and setting free a new sound: 'I was creating something new, something that came out of me.' As she performed, she was offering her audience members a lesson in how it would feel to be free."14 And, sensuality allows us to think about the relationship that Simone invokes in the arc of the song between blackness and love, which hinges on a shift in perception.

"Black is the Color" does this in part by more explicitly introducing the idea of blackness as one ("a" not "the") possible alternate epistemology that offers not merely critiques of what is, but entirely other modes of knowledge that can only be gleaned by thinking with perception in different ways. This is part of why I turn to the sensual: because its reliance on the flesh enables us to parse the knowledge that can be encoded in these excesses in different ways. Chambers-Letson argues that this knowledge through sensual excess is why he turns to performance, which is "a vital means through which the minoritarian subject demands and produces freedom and More Life at the point of the body. Minoritarian performance is what Nina Simone described as the art of 'improvisation within a fixed framework;' working within limited coordinates to make the impossible possible."15 Thinking with flesh and sense refuses to allow blackness to conform to one particular thing. In this way, not only does the loop gain a different meaning, but so too does the blockiness of the televisions and the way that they take up space, flicker, and emanate heat. These material dimensions shape how we perceive Benjamin's project. They add a physicality to Simone's vocals and the visuals on the televisions. They remind the spectator that their body exists in relation to this idea of blackness, endowing blackness with a personal quality that is still attached to formal qualities produced by the piece. That the porosity of the spectator's body co-produces an idea of blackness around the frame of the visual is important. It sidesteps questions of recognition and challenges what we think we know about representation.

These frames of knowledge circulate outside that of mastery and rely instead on individual negotiations between sensation and knowledge production. This work, I think, calls into question what we know and what we can do about form and the utility of formalism. Is form about epistemology? Is it about understanding the system of logic within which certain things reside? Blackness in its multiple valences gives us ways of thinking about several of these variables at once. In part, this meditation brings us back to the question of what kind of entity blackness is. This inquiry is separate from the question of race's reality, and asks instead whether blackness should be dealt with in relation to the question of form — what kinds of knowledges does it produce and how can these be interrogated? Thinking with formalism reveals both the faults in focusing on just one structure of knowledge production, but it also announces its utility in being able to see what gets produced as excess.

Amber Jamilla Musser is Professor of American Studies at George Washington University. Her research focuses on race, aesthetics, and sexuality. She is the author of Sensational Flesh: Race, Power, and Masochism (NYU Press, 2014) and Sensual Excess: Queer Femininity and Brown Jouissance (NYU Press, 2018).

In This Issue

Part 1

Introduction: Formalism Unbound

Timothy Aubry and Florence Dore

Good for Nothing: Lorrie Moore's Maternal Aesthetic and the Return to Form

Florence Dore

On Philosophical Imagination and Literary Form

Yi-Ping Ong

"Now can you see the monument?" Some notes on reading for "form"

Gillian White

Transformation and Generation: Preliminary Notes on the Poetics of the Memphis Sanitation Strike

Francisco Robles

The Sight of Life

Sarah Chihaya

Beyond Desire: Blackness and Form

Amber Jamilla Musser

Part 2

Form contra Aesthetics

Timothy Aubry

Zadie Smith's Style of Thinking

David James

Queer Formula

Joan Lubin

Formalism at the End Times: A Modest Account

Danielle Christmas

Furnishing the Novel, Feeding the Soul: Aimee Bender's The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake

Benjamin Widiss

Notes on Shade

C. Namwali Serpell

Afterword: Form Now: as Limit and Beyond

Dorothy J. Hale

References

- For more on Pure, Very, New, including the artist statement, see the exhibition website.[⤒]

- This mode of analysis is often attributed to strains of thought within Afro-pessimism and the work of Jared Sexton and Frank Wilderson, but others, such as Stephen Best, Rizvana Bradley, Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, and Calvin Warren also write adjacent to it vis-à-vis their focus on questions of blackness and ontology. See Frank Wilderson, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010); Jared Sexton, "The Social Life of Social Death: On Afro-Pessimism and Black Optimism," in Time, Temporality and Violence in International Relations: (De)Fatalizing the Present, Forging Radical Alternatives, ed. Anna M Agathangelou and Kyle D. Killian (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), 61-75; Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, "'Theorizing in a Void': Sublimity, Matter, and Physics in Black Feminist Poetics," South Atlantic Quarterly 117, no. 3 (2018): 617-648; Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, Becoming Human: On Blackness and Being (New York: New York University Press, 2020); Rizvana Bradley, "Living in the Absence of a Body," in "Black Holes: Afro-Pessimism, Blackness and the Discourses of Modernity," ed. Dalton Anthony Jones, special issue, Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge 29 (2016); Stephen Best, None Like Us (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).[⤒]

- Calvin Warren Ontological Terror: Blackness, Nihilism, and Emancipation (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 5-6.[⤒]

- See Bradley, Best, and Jackson above.[⤒]

- Carvell Wallace, "Nina Simone in Concert," Pitchfork, July 30, 2016.[⤒]

- Tavia Nyong'o, Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 11.[⤒]

- Kara Keeling, The Witch's Flight: The Cinematic, the Black Femme, and the Image of Common Sense (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007).[⤒]

- Lauren Berlant, "On Persistence," Social Text 32, no. 4 (2014): 33-37; 35.[⤒]

- Carl Rojas "Studio Visit: Paul Stephen Benjamin," Burnaway, April 9, 2014.[⤒]

- Amber Jamilla Musser, Sensual Excess: Queer Femininity and Brown Jouissance (New York: New York University Press, 2018). [⤒]

- Alexander Weheliye, Habeaus Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014).[⤒]

- Denise Ferreira da Silva, "In the Raw," e-flux 93 (September 2018).[⤒]

- Musser, Sensual Excess, 142. [⤒]

- Joshua Chambers-Letson, After the Party: A Queer of Color Manifesto (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 48. [⤒]

- Ibid. 4.[⤒]