Get in the Cage

Even if you're a true film buff, there's always that one classic movie that you haven't seen. Admitting it at parties is a reliable form of self-deprecating small talk: I actually haven't seen The Matrix, haha, can you believe that? When you're editing an entire Contemporaries cluster on Nicolas Cage, however, film-gap gaffes become a type of professional liability. When we realized that one of us (Devin) had never seen The Rock (1996), and the other (Kim) had never seen Face/Off (1997), each of them not only one of the other's favorite Cage films but also films that mark an important pivot in Cage's career, we realized that we had a necessary task in front of us.

While Cage, by the mid-1990s, had starred in numerous beloved films, provoking both critical acclaim and confusion, it is his action-hero turn in 1996 that propelled him into true stardom. In The Rock, a team of disgruntled Navy SEALs take over Alcatraz Island, threatening to shoot rockets of deadly nerve gas into San Francisco unless their demands (for government recognition and cold hard cash) are met. Cage plays Stanley Goodspeed, a chemical weapons expert who teams up with Sean Connery's John Mason, the only man to ever escape Alcatraz, to save the day. In Face/Off, Cage plays terrorist-for-hire Castor Troy opposite John Travolta's FBI agent Sean Archer. In order to discover the location of a bomb that Castor and his brother have planted somewhere in Los Angeles, Archer has Troy's face surgically implanted in place of his own. Things go awry when Troy wakes up, steals Archer's face, and steps into his life. Cage, back to playing a hero, saves his family, stops Troy, and restores his Travoltian visage.

What follows is the result of a couple of co-watching sessions, hundreds of WhatsApp messages, and a new and better appreciation of Cagean phenomena.

KQA: As the one who had never seen Face/Off, I feel like you really got the short end of the stick here. My love of The Rock essentially just reflects my terrible taste in movies, whereas Face/Off is a true gem of cinema, a ludicrous paean to the art of meta-acting. And we went into this thinking the films might be similar!

DWD: I think both of us (and most people) would agree Face/Off is the better film. But I don't think I ever properly understood what Face/Off is doing having not seen The Rock, which is a turning point in Cage's career. Prior to The Rock's release, he'd been an indie darling through films like Raising Arizona (1987), Moonstruck (1987), and Wild at Heart (1990). Immediately prior to The Rock, he starred in Leaving Las Vegas (1995), for which he won the Oscar for Best Actor — two-and-a-half months before The Rock's release. Watching Face/Off, as a kid in the early 2000s, I thought I was discovering the origin point for the Cage I saw in memes, YouTube clips, and movies both bad (National Treasure) and good (Adaptation). Revisiting it as an adult, I realize that Cage, in the mid-90s, had already had a full and enviable career. He was an actor at the height of his powers who could have, probably, done anything . . . and what he did was The Rock.

KQA: There are various theories throughout this cluster about Cage's seemingly inscrutable decision-making: JD points to a pre- and post-crash Cage, while Jordan pins it on a radical pluralism, an encompassing desire to have his cake and drink its blood, too. But this earlier moment — The Rock came out before Cage's finances collapsed, before he became a producer — is genuinely a little confusing. It's like he wants to have a real go at becoming the next James Bond. And as Kenton points out, this is in fact what tries to happen in The Rock: the only really Cagey performance is at the beginning, when Stanley Goodspeed's character is introduced. Thereafter, he just slowly gets Sean Connery'd to death.

But to your point about Face/Off and Cage memes: I don't think your kid self was wrong! This is exactly what it felt like to watch that movie for the first time as an adult: like you were watching just a two-hour accumulation of things that would wind up as GIFs. The only thing you really care about while watching Face/Off is everyone's varying ability to do a Nic Cage impression, including Nic Cage.

DWD: Absolutely. Castor Troy, Face/Off's over-the-top, golden-gun-wielding, choir-girl-groping, peach-metaphor-employing villain, is the role Cage was born to play: unhinged, grotesque, capable of anything — a Robert Crumb cartoon fallen into real life. But Cage only actually plays Castor Troy for the first 15 minutes, which is an entire Die Hard-style action movie crammed into one big set piece. After this, we never see Cage playing himself again, but the film nonetheless becomes about the performance he's enacted in this opening mini-movie. The plot is a series of elaborate excuses for allowing Cage to play Cage, Travolta to play Cage, and Cage to play Travolta playing (and almost becoming) Cage.

KQA: And what's interesting about that is that it doesn't work the other way around, because the leads are just so lopsided. Travolta does in fact get to play Travolta (as it were) in that wild first 15 minutes, but there are two films happening at the beginning of Face/Off: one stars Cage as a villain in the mode of, like, Sin City (or indeed that same year's Lord of War, which actually stars Cage), whereas Travolta's just in a cop procedural. So ultimately, there's no "Travolta" there to play. Which isn't a dig on him! I love Pulp Fiction as much as the next guy. But Woo could have cast anyone in the role of Archer, whereas as you say, Castor Troy is Nic Cage's id. Specifically. And Cage simply cannot play the straight man in the same way Travolta can, which is why his starring role in The Rock is so confusing (and also something I had not reflected on in any real way until watching these two films back to back).

DWD: It's true, and The Rock seems to recognize what a mistake it's made in casting Cage to fill that role. It has to go to almost absurd lengths to insist on Stanley Goodspeed's normality. He orders a vinyl copy of the first Beatles record and loudly declares "I'm a Beatlemaniac!": his defining eccentricity is loving the most popular band of all time. The scene when his girlfriend reveals to him that she's pregnant, as he practices guitar in his boxer shorts, is played completely straight and sincere. Later in the film, covered in blood and sweat, he tells Connery: "I lead a very uneventful life. I drive a Volvo. A beige one." While Castor Troy is some kind of trickster demigod — so irresistible that Archer, in taking on Castor's face, becomes him — Goodspeed is an empty cipher, or (like his musical hero) a nowhere man: "isn't he a bit like you and me?" That is, at least, the "you and me" The Rock wants its viewers to be or become.

KQA: I love the idea that somehow The Rock was like "oh shit, we somehow managed to cast Nicolas Cage as Stanley Goodspeed, the Most Normal Guy Alive, what do we do?" Something striking about watching these films so close together, and thinking they'd be somewhat similar, is how wildly different they are with respect to how they think about genre, even as they're both all about genre. The Rock is the straight man to Face/Off's Nic Cage, except Cage also stars in The Rock. How to fit him into a movie that cannot run counter to type in any way? It seems to me that what happens in response to that question is that Bay & co. wind up leaning, as you imply, so heavily into Goodspeed's "beige"-ness that it winds up horseshoeing around a bit and the normality becomes a little uncanny, particularly because in the first few minutes of the film, Goodspeed defuses a bomb while also giving a lesson on what sarin gas is. The Rock never really returns to this version of the character; it's a set piece to let us know (with a sledgehammer) that Goodspeed knows what he is doing in a realm of life — essentially, academia — in which the movie is entirely uninterested. Thereafter, Goodspeed is out of place in the world of the film, surfacing as that beginning character really only twice: in the film's best moment, and then to defuse the chemical weapons themselves, which requires (weirdly) nothing more than a bit of manual dexterity along with stomping on some computer chips. Of course, every Bond movie has a Q in it. But Q never sees any of the fighting; he just provides technical assistance from afar. The point of The Rock is to de-Q itself.

DWD: And that de-Qing is also a de-Caging (an unCaging?) in a way: it excuses Cage's presence, which is something the film seems almost embarrassed about. Stanley's eccentricities (the Beatles LP, the shirtless guitar-playing) recall Cage's earlier, almost Elvis-inflected performances in films like Valley Girl and Wild at Heart. Pairing this indie quirkiness with that encyclopedic knowledge of chemicals and coolness under pressure promises a synthesis between Cages old and new, but the film gives us the classic model just to abandon it, to assure us it won't get in the way of the action. Then you turn to Face/Off, a film that not only isn't embarrassed about Cage but is obsessed with him. During those early scenes, the camera is in love with Cage, shooting him in almost operatic fashion. He seems capable of anything: sniping children, duel-wielding golden dragon pistols, groping choir singers while in priestly garb. Travolta, by comparison, is shot in a tight, claustrophobic style that recalls an also-run Law and Order or a high-stakes version of Office Space (compare the two shots below, which happen almost back-to-back). That is, until the face-swapping, which makes little sense, but is ultimately about letting everyone else in on the fun: it untethers Cage from his individual body and allows him to spread through the film like a virus.

KQA: Viral Cage! So much better than the virus we're all caged in by, now. Coming to Face/Off action-film-Cage after The Rock action-film-Cage was like watching a painting being restored. The Rock promises a Cage we never get. Face/Off, on the very other hand, is a movie that's custom-tailored for the guy. Watching Face/Off for the first time after having seen The Rock multiple times is to get an object lesson both in genre and in Cage: in other words, while I agree with you that The Rock is definitely the blockbuster inflection point in Cage's career, it seems to me that it took Face/Off for the genre of "action film" to figure out how to use Cage properly. There are, obviously, many things wrong with Face/Off's politics, but whatever they are, at least they don't smother the Cagean excess in a layer of Deep Thoughts About The Troops.

DWD: You're totally right that Face/Off is the first action film to use Cage properly (Con Air comes out in between these two, and while a much more bonkers ride than The Rock, still wants Cage to be the clean counterpoint to its pulpy villains), and I think it does so not just by letting Cage loose but by taking a Cagean approach to the action film genre itself. As Veronica writes in her piece, Cage both invites and frustrates dichotomous thinking between "good" and "bad," "irony" and "sincerity." Face/Off courts this approach, with the evil and zany Castor taking on the good and tepid Archer. This good versus evil opposition (one it self-consciously traces back to Greco-Roman myth and Christian theology, with its Homeric character names and operatic church shootouts) lends the film its narrative coherence, but it is less interested, I think, in maintaining, or even undermining, the opposition than it is in using its black and white chessboard as a space for free play.

I don't want just to assert that Cage and Face/Off are deconstructing the action film. I don't think the film just wants to say "A-ha! It's all fake! Everything is a performance! It's Cages all the way down!" Nor do I think we have to read it as affirming the dichotomy in its disappointing ending, in which Castor's son is adopted by Archer and the family unit is restored, Cage-free. I think the film is less about these two poles than the space between them. Perhaps what it wants to do, in a decade of aesthetic exhaustion, is show us how much bandwidth remains to be explored in our tired old forms. This is how the film utilizes Cage to his fullest, by enabling him not just to be an outrageous comic book villain or a sincere hero, but to modulate his dynamics so as to find the spaces between. This is why, for me, while the titanic clashes that open and close the film, played at fortissimo, are the most memorable, the most interesting remain the tiny moments in the middle of the film, where Cage finds the mezzo-piano and mezzo-forte notes, as when he, playing a drug-addled Archer-impersonating-Castor, continuously repeats the name of the film: "I'd like to take his...his face...off.... His face...off." In this sense, that corny movie moment we all love ("They said the name of the movie!") becomes something disturbing, and we cannot confidently state where on the Castor-to-Archer spectrum we are. Cage finds a new spot on the board not by venturing outside its boundaries but by jumping, like a knight, in a move that briefly explodes the game into three dimensions.

KQA: The Rock ostensibly tries for a little bit of the gray area you describe, too: while its narrative structure is also dependent on a good/evil dichotomy, for a not insignificant part of the movie, there are essentially no bad guys, because you're supposed to sympathize with the terrorists. They were wronged! Lead hostage-taker General Hummel (Ed Harris) gets more praise heaped on him than anyone else in the film. We learn about his exploits via the White House chief of staff listing them for the viewer's benefit: "three tours in Vietnam; Panama; Grenada; Desert Storm, three Purple Hearts, two Silver Stars, and the Congressional Medal of...Jesus. This man is a hero." The lead-up to one of the film's climactic scenes, in which a host of Navy SEALs are massacred by Hummel's men, involves the SEALs' commanding officer reiterating how much he agrees with Hummel's position, before being shot multiple times in the chest. The film's real villain is the director of the FBI (John Spencer), who — as a stand-in for, somehow, both the State writ large and the average civilian — reveals himself to be strikingly uninformed about military black ops and thus insufficiently deferential to the troops. Face/Off's conservatism is socio-familial and only shows up at the (dismal) end; The Rock's, on the other hand, is geopolitical and forms the entire premise of the movie. And for some reason, that level of pure ideology, as it were, boxes Cage out: again, there's no room for an actor of his stripe in a film that must at every turn reiterate (often literally, in dialogue) its political commitments. In The Rock, Cage's hamfistedness meets, and is actually defeated by, the hamfistedness of the military industrial complex.

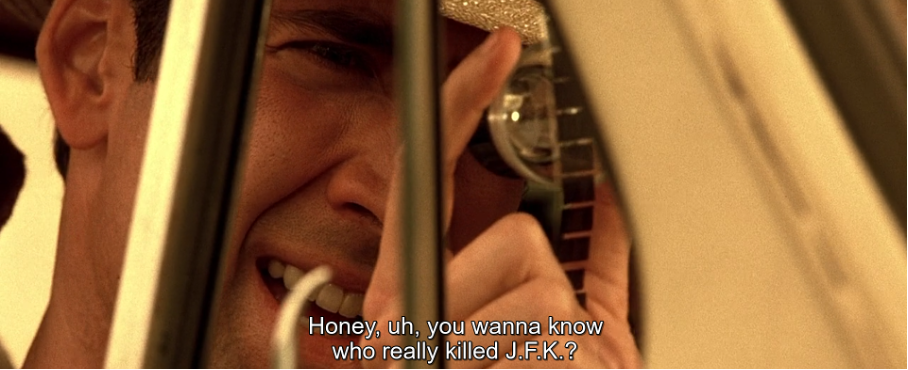

DWD: And as a first-time watcher, that's what kept hitting me in the face: the desperate need for me, the viewer, to sympathize with the troops (who want nothing more than recognition — and a million dollars each — for all that they've done). I kept holding out hope that Cage would save me from this, but I suppose even he is no match for the ideological power of US exceptionalism (see another of his low points, Oliver Stone's 2006 World Trade Center). It makes me wonder, though, if I failed to see the Cagean alternative because I was looking for it. I can't know what it was like to see this movie in 1996, but I wonder if some of those viewers went to see a militaristic romp and came away with even just a trace of the fever that works its way through Face/Off. It's not dominant, but it's there: in the shirtless guitar-playing, the operatic bomb-in-a-baby-doll dismantling, and that final shot of gonzo-Goodspeed, newly married, peering into a trove of national secrets, the parting gift from Sean Connery's John Mason. "You wanna know who really killed JFK?" he asks us, and most Rock viewers probably don't! But maybe some did.

KQA: It's a question that the film absolutely can't answer, and not only because its viewers probably don't care. But nevertheless, there's Nicolas Cage asking it, in the middle American dust, and those of us who do in fact want whatever maximalist history is in those microfilms will just have to follow his car, cans rattling, into the weird distance.

Devin William Daniels (@stalecooper) is a Ph.D candidate in English at the University of Pennsylvania. His work is published or forthcoming in Mediations, English Studies in Africa, and Hyped on Melancholy. He is co-host of the podcast You're Tall but I'm Standing in Front of You.

Kimberly Quiogue Andrews is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Ottawa. She is also the author of two volumes of poetry: A Brief History of Fruit (University of Akron Press) and BETWEEN (Finishing Line Press). You can find her on the bird-site at @kqandrews.