Get in the Cage

Who is Nicolas Cage? The name itself is enough to conjure a whole host of associations not easily reconciled. There's the star of beloved indies like Raising Arizona (1987) and Wild at Heart (1990), the action hero of Con Air (1997) and National Treasure (2004), and the Oscar-winning/nominated performer in Leaving Las Vegas (1995) and Adaptation (2002). There's Nicolas Kim Coppola, the heir of cinematic royalty hiding in plain sight; there's the money-crazed Cage of absurd opulence and subsequent financial meltdown; and, perhaps more than anything, there are the memes. Regardless of how many Cage films you've watched, you've almost certainly encountered him as a .gif, a YouTube supercut, or in a clip like the famous scene from The Wicker Man (2006), in which Cage screams "Not the bees! Not the bees!" as he is tortured to death by the white-clad cult that walked so Midsommar's could run.

To certain, terminally-online generations, Cage's melittological demise might be his most famous on-screen performance: except, of course, for the fact that this scene wasn't in Wicker Man. It was, rather, part of an alternate ending included on the film's unrated DVD release. If you watch in anticipation of this scene, you'll find Cage's screams reduced to ephemeral background noise playing over the cult's procession to the film's eponymous basketcase (Fig. 1), with the images of torture cut in exchange for a PG-13 rating. Nonetheless, the meme has outshone the movie. While Wicker Man failed to break even on its $40 million budget, the most popular YouTube version of the clip (uploaded May 2013) has accumulated 3 million views (a metric that doesn't take into account years of viral spread through other platforms).

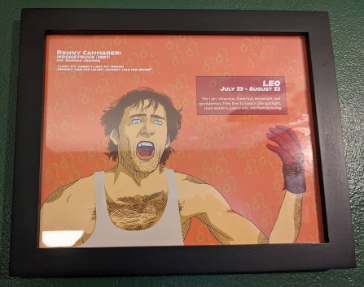

That Cage's most popular meme performance never actually made it to the silver screen highlights the degree to which he, as a cultural object, circulates not just through his films and performances but through the various media by which we digest, react to, and remix them (whether we've seen the source text or not). This "discursive Cage," as contributor J. D. Connor calls it, emphasizes the ridiculous, absurd, and freakish aspects of Cage's performances. The diegesis — characters, settings, temporalities, genres — falls away, as Cage-in-himself becomes a sort of joke without a punchline — or a joke to which he is the punchline. We're able to laugh at Cage from afar without being implicated in what he's doing or having to think about it too hard: context doesn't matter, it's just the purity of an actor doing something that is, obviously, ludicrous, an embarrassing excess, acting so bad it's good. This Nic Cage garners a fandom rooted in irony and disavowal, evidenced not only by the memes themselves but by the surplus of Cagean commodities, a temptation to which the co-editors of this cluster are not immune (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2: one's editor's notional treasures

But the explicit irony of Cage fandom belies a persistent fascination rooted in genuine appreciation. Many bad performances have produced flares of fandom, a la the midnight screenings of The Room, and many actors have generated a meme or two. In the digital world's surfeit of bad content, Cage would not be as ubiquitous or long-lasting as he is if he weren't speaking to us in a more complicated way. Even during his career nadir, when his financial constraints precipitated a great number of low-budget and direct-to-video releases, he remained an object of critical fascination and even hope (perhaps no actor has "returned to form" more times over the past decade). His career's twists and turns have provoked examinations both scholarly and popular, as in the episode "Introduction to Teaching" of the comedy series Community. Abed (Danny Pudi) enrolls in a college course on Nicolas Cage and loses his mind trying to objectively determine if he is "good" or "bad" (Fig. 3). Cage's oeuvre offers unlimited evidence for either answer, with every example almost immediately canceled out by a counterexample.

Fig. 3: The seduction of certainty.

The difficulty of the good/bad question ultimately says less about Cage himself than about the terms on which we judge acting and, consequently, film. His performances are almost surreal, a far cry — often literal — from the cinematic naturalism we often associate with "good" acting. But then again, how exactly would you act if your head were being tortured with bees by a cult on a remote island before being burned alive?

One of the major appeals of Cage's acting style is that it gives expression to emotion, anxiety, and rage we all feel but can't express in a socially-appropriate manner. Cage himself has theorized his acting as "Nouveau Shamanic," a characterization that draws (deeply appropriatively) on sources as diverse as Indigenous religious practices, German Expressionism, and kabuki theater. Understanding Cage on his own terms requires that we reassess what good and bad acting even are outside the dominant frame of naturalism. If you want to see something outside of this frame, there are plenty of places to look, but the particularity of Cage might lie in how he so aggressively and consistently throws himself, like a Brechtian wrench, into what by all means should be standard-fare Hollywood productions. From this angle, even the Cagean meme is less a joke than a question: what, exactly, is going on here?

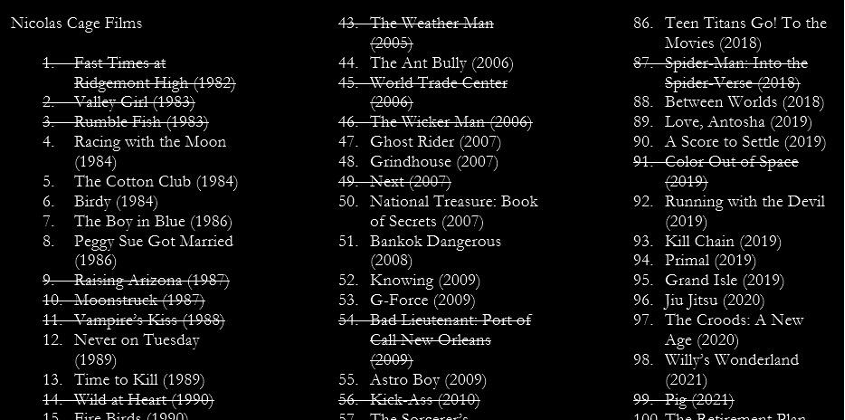

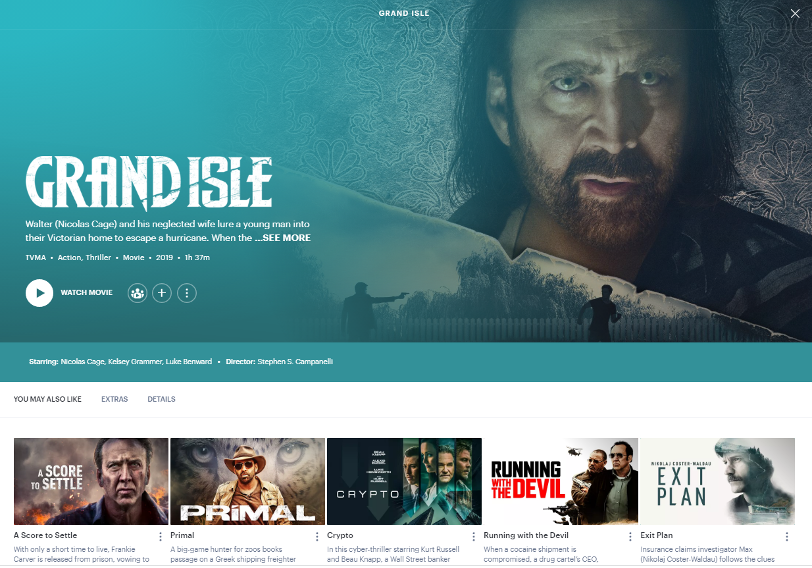

This question feels particularly germane a year and a half into a pandemic in which we have all been told to act normally, while having to engage in constant microcalculations about what normal is. For many of us, the months of confinement were filled with a pacifying stream of film and television, and several contributors to this cluster found Cage to be a particular refuge. The sheer size of his filmography (at least 99 movies by our count, with the 100th — and beyond — coming down the pipe) ensures that even superfans have plenty left to watch (Fig. 4), and digital streaming services' algorithmic logics have clearly identified Cage as a genre unto himself, ushering the viewer from Cage to Cage with minimal friction or decision fatigue (Fig. 5). Appropriately, this is also the year of Cage's latest career resurgence, with 2021's Pig achieving critical acclaim, building upon the recent successes of Mandy (2018) and Color Out of Space (2019). Amid this resurgence, however, there is the undeniable fact that the ironic conception of Cage is no longer the creation of viewers after the fact, but is rather being prepackaged and sold as a product: even great films like Mandy draw on this, but it is most palpable in projects like his hosting of the Netflix series The History of Swear Words (2021), his destructions of animatronic animals in Willy's Wonderland (2021), and the upcoming 2022 release of The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, a work of metafictional fan service in which Cage, playing himself, will diegetically revisit many of his iconic past performances at the behest of a billionaire superfan.

What would it mean to take Cage seriously? Recognizing that such a question requires more than one answer, we've collected a group of writers who take on Cage in myriad ways, producing myriad Cages. J. D. Connor links the aforementioned "discursive Cage" to the frustrations of the Great Recession: as the US government failed to offer a transformational response to the 2008 financial crisis, a financially-strapped Cage both channels this era's frustrations and locates a strategic zone in film distribution through which to convert his name recognition into a string of low-risk, high-reward releases. Connor sees Pig as perhaps signaling a new era in the Cagean persona, a possibility Miles Taylor takes on directly, reading the film as staging a confrontation between two Cages — the capital-earning action star and the auteur working for art's sake — who prove irreconcilable.

The dichotomy of action-Cage and auteur-Cage appears throughout a number of other pieces in this cluster, including our own. In a dialogue of first-viewings, the two of us puzzle over the 1990s action genre's attempts to incorporate Cage in The Rock (1996) and Face/Off (1997), which they do in both surprisingly different ways and to greater and lesser success. Kenton Butcher, meanwhile, confronts how his childhood love of Cage's 90s blockbusters is tied up in their undeniable ideological investments in neoliberal colorblindness and carceral logics. The auteur-Cage returns in Nathan Lee's piece, which examines Color Out of Space toward understanding Cage's unique unhingedness in Lovecraftian terms: as an object we cannot understand but are nonetheless transfixed by. The inexplicable transfixion that Cage elicits provides a pedagogical function for Nitin Govil, who draws on his own Nicolas Cage-themed college course to query the difficulties of teaching and learning from our obsessions.

The vocabularies of horror and obsession similarly inflect our other contributors' attempts to ascertain Cage. Jordan Brower takes a capacious look at Cage's career as both an actor and producer, observing how he frequently took recourse to the figure of the vampire, in literal and more subtle ways, to capture a state between life and death, character and star, that defies schematic dichotomies. Finally, Veronica Fitzpatrick looks to the actor's eyes for a view of Cage that resists mutual exclusion. Exemplifying our cluster's goal, she sees in Cage not a "good" or "bad" actor but a figure looking back and asking us to see alongside him. Taken together, these pieces offer a kaleidoscopic vision of Cage — and it's this colorful, shifting, and mildly hallucinatory view, we think, that his work so rigorously and consistently demands.

Devin William Daniels (@stalecooper) is a Ph.D candidate in English at the University of Pennsylvania. His work is published or forthcoming in Mediations, English Studies in Africa, and Hyped on Melancholy. He is co-host of the podcast You're Tall but I'm Standing in Front of You.

Kimberly Quiogue Andrews is Assistant Professor of English at the University of Ottawa. She is also the author of two volumes of poetry: A Brief History of Fruit (University of Akron Press) and BETWEEN (Finishing Line Press). You can find her on the bird-site at @kqandrews.