Get in the Cage

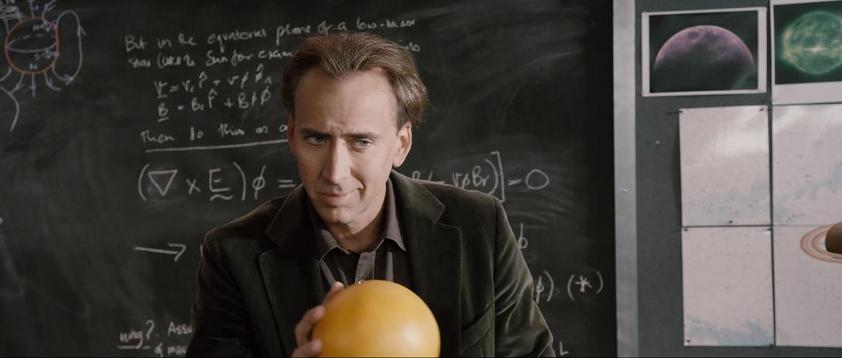

One of our first encounters with Nicolas Cage in Alex Proyas's 2009 film Knowing takes place in the university classroom. His character, Professor John Koestler, is giving some astrophysics students an impassioned oration on the nature of the universe. Walking over to a heliocentric model of our solar system, Koestler plucks the star's yellow orb from the center of the model and tosses it to one of his students (fig. 1). "Tell me something about the sun," he asks, as the student catches the celestial object. "It's hot," deadpans the student, as the class bursts into laughter.

Knowing's scene of instruction neatly captures my trepidation as I began teaching an undergraduate Nicolas Cage course last summer. Recalling Richard Dyer's linkage of film stars with their cosmological brethren, associating the practices of celebrity worship with the adoration of other "heavenly bodies,"1 I wondered how my students would answer when I tossed them the topic of Cage's singular luminosity: "so, tell me something about this star?" Would they answer with an abrupt single-word appraisal like Koestler's student: that Cage is "angry" or "unhinged"; his acting is "bad" or "excessive"? Would students accustomed to a steady stream of digital memes, with their terse distillations of Cage's career,2 be willing to pay any attention to our star beyond a passing glance?

I needn't have worried. Writing "Nicolas Cage" into the course title garnered a somewhat self-selected group attuned, at the very least, to the last ten years of wide accolades. These include Cage's critical and commercial success after Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (Werner Herzog, 2009), from lauded performances in Joe (David Gordon Green, 2013) and Mandy (Panos Cosmatos, 2018) to Pig (Michael Sarnoski, 2021). I was right about their encyclopedic knowledge of Cage memes, particularly in the case of The Wicker Man (Neil Labute, 2006), which seems to have supplanted Vampire's Kiss (Robert Bierman, 1989) as a touchstone for Cagean superabundance (see Fig. 2).

I was also wrong to think that the digital meme would narrow our classroom engagement to terse assessments. The class understood the meme's viral effect as an appropriately generative way to consider the abiding cultural association between Cage and ornamental display. In other words, what seemed like an attempt to restrict (cage?) the star in a limited digital frame only served as a dynamic opening (uncaging!) into the world of proliferating excess. And this is where our class conversations spun in all sorts of intriguing directions, including documenting the delightfully myriad influences on Cage's gendered performativity, from Max Schreck, James Dean, Superman, and Elvis to Evel Knievel, Klaus Kinski, and Woody Woodpecker — where what we know of Cage is contrasted with what we know about his sources. In the case below, we can see this contrast through a reflexive juxtaposition of performative surfaces (Fig. 3 below).

These influences are often invoked through deliberate homage in Cage's film roles, through costume, hairstyle, gesture, and of course accents, vocal inflections, and phonetic embellishments. Our class was keen to engage the latter, specifically the expressive register of poetic exaggeration, particularly when we learned how Cage's early performance debts ranged from Jean Marais in Beauty and the Beast (Jean Cocteau, 1946) to Pokey in The Gumby Show. My students concluded that Cage's preferred film genres — expressionism, fantasy, horror, science-fiction, and comic book seriality — situated his character's exaggerations within the generic protocols of mythic speech. We also took Cage's theatrical inflections as a distinctive claim to his craft. While he has largely abandoned method acting after Birdy (Alan Parker, 1984), Cage retains its heightened, heroic sense of commitment, with many of his roles inscribed within the performance of hyperbolic dedication.

As his Stanley Goodspeed puts it in The Rock (Michael Bay, 1996), "I'm not a chemical freak, I'm a chemical superfreak." The spirit of this sentiment accounts for an entire history of professional portrayals. Cage's workers are voracious exaggerations of actual specialist activity. Unrelenting and over the top, his bakers, FBI agents, writers, literary agents, gamblers, medics, cops, lumberjacks, military veterans, assassins, thieves, hunters, and even his drifters possess a sense of commitment bordering on, and frequently veering into, obsession. Whether this translates into generally recognizable success to the prevailing administrative authority often isn't the point. That's why, when his character finally gets a long-sought after tenure letter in Pay the Ghost (Uli Edel, 2015), it's addressed from a nameless university (see fig. 4).

Terence McDonagh, Bad Lieutenant's hard-charging and hard-living detective, played by Cage in a performance that serves as a career summation, puts it this way: "it's amazing how much you can get done when you've got a single purpose guiding you through life." Cage's jobs — as well as his own acting — often careen towards accomplishment, blazing through conventions of vocational progression. The staging of over-achievement onscreen is usually accompanied by (and sometimes through) self-destructive character addictions to revenge, alcohol, drugs, gambling, and bad investments, the last of which crosses over into well-documented off-screen celebrity excess (see fig. 5, for example).

Among these many performances of work, Cage hasn't played a teacher all that frequently, but it is a role he insists on having acquired as an inheritance. "I grew up with a professor, so that was all the research I ever needed," responded Cage, when asked about his preparation for Knowing.3 Cage's father, August Coppola, was a comparative literature professor in the California State University system, while his brother, Francis Ford, went onto a certain degree of success in the filmmaking field, as you're probably aware. Coming up, then, not only as a son of a professor but also as a Coppola, Cage rejected the patrimonial advantage of a famous surname in his real profession, while seeming to embrace hereditary opportunity when it came to preparing for his on-screen portrayals.

In Knowing, Cage's Koestler, grieving over the recent loss of his wife, asks his students about their thoughts on "randomness and determinism in the universe." When they turn the question back onto him, asking "what about you Professor, what do you believe?" Koestler responds, shaking his head, "I think shit just happens." This initial cynicism is moderated during the film as he deciphers a fifty-year-old numerological and alphabetical code, realizing that past literary inscriptions are indeed portents of the future. Cage's on-screen hermeneutic heroics are deployed again in Seeking Justice (Roger Donaldson, 2011). Here, Cage plays an English teacher at a New Orleans high school, where we are introduced to him teaching Shakespeare's Sonnet 129, the one on "lust in action." He implores his students to recognize the dramatic possibility of "violent words," a dark harbinger of the brutal sexual violence about to be committed against his wife. Similarly dark portents abound in Pay the Ghost, where Cage plays Mike Lawford, a poetry professor we first see studying Goethe's poem Erlkönig ("The Elf King"), about a child's supernatural tormentor and a father's attempted rescue — another poetic augur of the film's dramatic arc.

Taken together, Cage's lack of research for teaching roles, his theatrical recitations, and his impassioned pedagogy in these three films reverberate with dynamic foreshadowing. Patrimony, prophecy, and poetry function as coded messages from the past. In a similar register, celebrity culture is also about divination: cosmology and charisma both have origin stories. In this way, Professor Koestler's question about randomness and determination in the universe can be read as an astrological inquiry into the nature of stars (see fig. 6, in case you were wondering). In my Nicolas Cage class, we followed this esoteric line of inquiry in what turned out to be a determinative act of divination.

During an October 1986 press junket for Peggy Sue Got Married (Francis Ford Coppola, 1986), as film critics called Cage a "movie wrecker," he appeared as a guest on the The Dick Cavett Show.4 Actor Carol Kane was also in attendance, but the main event of the night was an appearance by Miles Davis. As a bit of a lark, Cage brought along a trumpet in the hope that it would get Davis's blessing (see fig. 7.). This led to a somewhat stilted lesson in trumpet playing posture, followed later in the show by Davis's advice that performative imitation should always be rejected in favor of "playing sideways."

In Cavett's interview with Cage, the actor described his abandonment of method acting in favor of more experimental approaches, such as strolling the aisles of Toys "R" Us, plucking random toys from the shelves, and taking them home to play with as acting inspiration. As Cavett inquired into the performer's penchant for "future acting over the edge," Cage described how such idiosyncratic aesthetic practices might serve as predictive forms for the destiny of art. Cavett then shifted the line of questioning towards Cage's physical appearance. Suggesting a resemblance to the actor Robert Mitchum with an observation about his "young, Mitchum-like looks," Cavett asks, "do you see any of Mitchum in yourself?" "Not really, no," Cage responded, with a brief but penetrating look at his inquisitor (fig. 8).

In our class, we had already read an excerpt from a celebrity biography of Cage, describing his parents' contentious marriage and one specific argument where his mother, Joy Vogelsang, told his father of a supposed affair with Mitchum. This, in turn, became a source of August Coppola's enduring ire towards his son. In Nicolas Cage: Hollywood's Wild Talent, Brian J. Robb quotes Cage directly on the incident:

'The Mitchum business started with they were fighting and she wanted to get a rise out of him,' said Nic of his father's suspicions. 'She said to him, "Nicky's not your child." She had a signed photograph of Robert Mitchum which said: "To Joy, Love and Kisses, Bob" and she always made hints. Obviously, nothing happened. She was just a young lady in a dance group and Mitchum was around and she got an autographed picture. She admitted to me that she told him that in the heat of anger. I'm sure she doesn't feel good about it, but you know how people say things in the heat of anger. I've lived with that anger from my father for thirty years.' 5

Could Cavett have known about this family drama of origin in asking about Cage's resemblance to Mitchum? Or had his characteristic snark transmogrified into an accidental divining rod, tapping into a rich vein of backstory? Casting celebrity divination in terms of a Hollywood Oedipal drama might seem a bit outlandish. But, after all, we are dealing with Nicolas Cage, who has entered romantic relationships with the daughters of his childhood idols like Micky Dolenz and Elvis Presley, paternal pop culture surrogates in the absence of his own father's care. This certainly bears some conceptual resonance with Cage's determination of performance talent. "I do believe that you're either born with it or you aren't," Cage says of acting. "It's a gift. You either have this ability to go into that film dimension and be charismatic or you don't, and it's not something you can really learn."6 Biological predestination aside, might this statement serve as the enduring lesson of my Nicolas Cage class?

"The first task of education," insisted Sigmund Freud, is "to inhibit, forbid, and suppress."7 Speaking to the impossibility of instruction, Nicolas Cage, as a real-life teacher, seems to agree. While he has taught numerous acting masterclasses over the years, Cage insisted to a recent SXSW audience that they "always stay a student — never be a maestro."8 If celebrity knowledge remains similarly imminent rather than mastered, and if Nicolas Cage is to be our guide to the pedagogy of obsession, then perhaps all we need to do as students is to gaze at the heavens and wait for the stars to align (see fig. 9).

Nitin Govil (@nitingovil1) is Associate Professor of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California. He is the author of Orienting Hollywood: A Century of Film Culture between Los Angeles and Bombay and one of the coauthors of Global Hollywood and Global Hollywood 2.

References

- Richard Dyer, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society(New York: St. Martin's Press, 1986).[⤒]

- David McGowan, "Nicolas Cage - good or bad? Stardom, Performance, and Memes." Celebrity Studies, 8, no. 2: 209-227.[⤒]

- Erin McCarthy, "Knowing Blends Science Fiction Fact with Fiction." Popularmechanics.com, October 1, 2009. [⤒]

- Dick Cavett, "Nicoas Cage on His Acting Technique," YouTube video, 10:03, November 18, 2019.[⤒]

- Brian J. Robb, Nicolas Cage: Hollywood's Wild Talent (London: Plexus, 1998), 11.[⤒]

- Jason Bailey, "The Most Nicolas Cage Moments From Nicolas Cage's Master Class," Vulture, December 10, 2018.[⤒]

- Sigmund Freud, "New Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis" (1933/1961), in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 22, edited by J. Strachey (London: Hogarth Press), 149.[⤒]

- Quoted in Nigel M. Smith, "Here are the best things Nicolas Cage said during his career-spanning SXSW talk." IndieWire.com, March 11 2014. [⤒]

- Excerpted from https://www.popsugar.com/celebrity/Nicolas-Cage-Wearing-Nicolas-Cage-T-Shirt-34949330.[⤒]