Get in the Cage

In 1995's Leaving Las Vegas, Nicolas Cage is Ben Sanderson, a terminal alcoholic closing out his remaining time on earth with sex worker Sera (Elisabeth Shue). In their first meeting, Ben nearly hits her with his BMW on the Strip. But subsequent weeks see him play the doleful, rascally stray dog to Sera's benevolent fosterer — her so-called "sad puppy," alternately bleak with gratitude and anarchic when left on his own. The role occasioned Cage's lone Oscar win to date; well-documented are the lengths to which he went crafting a naturalistic embodiment of moribund drunkenness, but key to the "crumbling elegance" he's since described striving for are moments not of turbulence, but lucidity, like when Sera unsheathes a cigarette on their first real date and he swings from being incapable of guiding spaghetti into his mouth to one-handedly striking a match without blinking: a flicker of poise and presence whose precision outstrips all prior absurdity.

Ben Sanderson isn't just Cage's most industry-commended performance; it's a pithy demonstration of what he does best, or perhaps what he can't help himself from doing: bounding between affective and energetic registers in a manner irreducible to the rubric of range. My father once described inheriting his left-handedness from his father, a teacher, who was trained to write the "right" way and ended up able to start a thought at one end of the blackboard and finish at the other, passing the chalk smoothly from left to right like a baton. Whereas an actor with even admirably broad range tends to vary their style from project to project, Nicolas Cage's approach is distinctly and improbably ambidextrous within works, such that a single role is liable to showcase both Nic Cage-as-puppy, characteristically sad-eyed and piteous, and what fans of Moonstruck and Wild at Heart would recognize as the wolf: a snakeskin Sailor somersaulting out of the black Thunderbird. Ronny Cammareri calling out for the big knife.

Like a lab-grown case study for criticism, Nicolas Cage is both an irresistible invitation to, and a diabolically resistant object for, dichotomous thinking. More than any other living Hollywood actor, his comprehensive persona — the totality of onscreen appearances, trivia, gossip, credit reports, marriages, memes — inspires oppositional arguments: some elegant ("The method and madness of Nicolas Cage"), many dull ("The Highs and Lows of Nicolas Cage"), but nearly all encompassed by the jejune title of a class featured on the fifth season of Community, "Nicolas Cage: Good or Bad?"

Naturally critics have remarked on the reference. For Sam Adams, such a question, taken seriously, is "less an A/B proposition than a Zen koan." In her book, National Treasure, Cage-enthused author Lindsay Gibb considers Community creator Dan Harmon's enigmatic account of his inspiration: "Nicolas Cage is a metaphor for God," he said, "or for society, or for the self, or something . . . Is he an idiot? Or a genius? Can you write him off, or is he inexplicably bound to your soul?" What's key to ruminations like these are their conjunctions; when we hold together all that Cage is, hoping to reconcile his hallmark rage with his hangdog silence, it's with an or or and that respectively overdetermines the critical conclusion. Either the stupidity of his more mediocre projects eclipses the sincerity of his efforts within them, or he simply contains multitudes, and you can't throw out the arthouse baby with the blockbuster bathwater (or vice versa, according to taste). Better suited to the Cage question might be the exclamatory grammar of Le Tigre's 1999 track "What's Yr Take on Cassavetes?", where alternative interpretations of the titular filmmaker — Alcoholic! Messiah! Genius! Misogynist! — sonically compete, invert, and overlap, until what we discern in a spectrum of values is more chaotic than mere discrepancy. That's a lot closer to the view Cage compels, one that rejects mutual exclusion: where, as for a raving Hamlet, even the appearance of madness is appreciably methodical.

Gibb's book works to historicize that method, breaking it down into eras and modalities familiar to Cage aficionados. The "counter-critical" non-naturalism of Peggy Sue Got Married, the avant-garde "Western Kabuki" of Vampire's Kiss, and the "Nouveau Shamanic" (read: crystals in pockets) approach to Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance each appear to support the finding that Cage's work is earmarked by two qualities thought exceptional to contemporary Hollywood filmmaking: eclecticism ("Cage is experimental in the decidedly unexperimental terrain of Hollywood feature films") and earnestness ("Cage is a reminder that it's okay to care, even if it makes you look ridiculous").

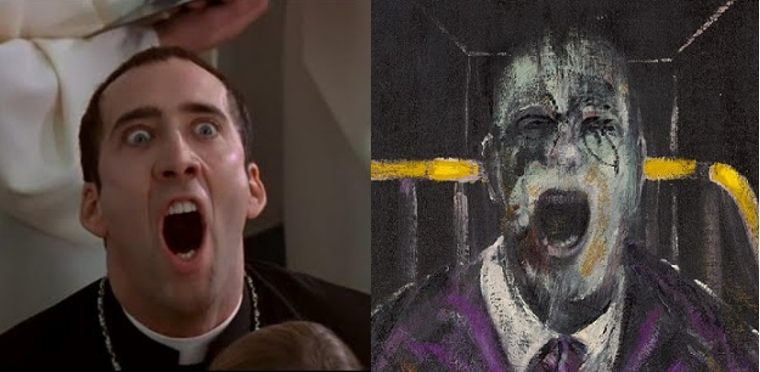

What strikes me is the extent to which both effects depend on, and are manifest through, the eyes of Nicolas Cage. We need only think of Face/Off 's "Hallelujah!" close-up, where two handfuls of choirgirl ass prompt from Castor Troy an expression of profane electrocution — Cage's take on Francis Bacon's screaming pope. "Those eyes . . . " Meg Ryan sighs in City of Angels, decompressing from her surgical rotation in a steaming bath, musing as she presses an icy Rolling Rock against her cheek. "The way he looked right . . . right down into me." She thinks she's having a private, Cadbury Flake-type moment, but we know Cage's angel Seth is studiously lurking, all-seeing and unseen. Plaintive, searching. Not unlike the grateful look he gives Cher's new dress at the opera. Not unlike the look he fixes on Elisabeth Shue in the car, apparently spellbound by the spelling of her name (s-e-r-a). The eyes of Nic Cage don't even have to open: the second we meet Con Air's parolee Cameron Poe emerging in slo-mo from the prison transport bus, smiling in handcuffs, turning his face up toward the sun — this, too, is presentational, not in terms of bravura histrionics, but making breathing look like breathing. Under his eyelids, the unburnished pleasure of being alive no matter what. Vampire's Kiss is better known for Cage's diegetic consumption of a live cockroach — the notoriety of which Cage himself acknowledges, remarking (lamenting?) in his Cal State Fullerton commencement address, "You can become very famous very quickly by eating a cockroach in a movie" — but thanks to his sustained evocation of a googly Max Schreck, it's his sclera that stay with you, their scale and pallor; one wonders if his approach to playing literary agent Peter Loew was less about reviving a German Expressionist mode of graphic presentation than testing the physical limits of how widely the eyes can open, and for how long.

***

It's tempting to construe such techniques as hailing from outside of — and signifying a stylistic departure from — Hollywood, but maverick sensibilities have long found their way to US studios via the ongoing and often mutual circulation of work and workers; only five years after Nosferatu, F. W. Murnau made his American debut with Sunrise (1927) at Fox. In other words, how "decidedly unexperimental" we deem the terrain of American filmmaking depends on our dual adherence to historical nearsightedness and a popular but hopefully waning attachment to viewing Hollywood style as apart from, and diametrically opposed to, well, everything else — but specifically to David Bordwell's conception of "art cinema" style: that which is elliptical and opaque, indifferent to narrative resolution and attentive to psychological complexity.

Throughout his career, Cage has not only bridged that ostensible gap, but undermined what appears to be the extent of its span. Ethan Hawke's somewhat infamous fawn (on a 2013 Reddit AMA) that Cage is "the only actor since Marlon Brando that's actually done anything new with the art of acting" encapsulates the chronology problem of reconciling citation with innovation when it comes to film style; what appears new only looks so in context. "[H]e's successfully taken us away from an obsession with naturalism into a kind of presentation style of acting that I imagine was popular with the old troubadours," Hawke explains. Described thus, Cage's unique style is at once new (fresh, atypical, even avant-garde) yet historic: animated by a magpie cinephilia whereby all methods in all eras are equally up for grabs. In Moonstruck, he's tapping Jean Marais's gruff delivery in Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast; under Adaptation courses Jeremy Irons's performance of twin gynecologists in Cronenberg's Dead Ringers.

And by a certain point, Nicolas Cage is seen as riffing on Nicolas Cage. Hawke's reference to Marlon Brando reminds me (and writer Sonny Bunch) of Pauline Kael's 1966 essay on the late star's plummet from integrity and relevance to self-parody, a decline Kael finds symptomatic of the studio system's foundational impatience. "The organic truth of American movie history is that the new theme or the new star that gives vitality to the medium is widely imitated and quickly exhausted before the theme or talent can develop," Kael writes. "The industry makes tricks out of what was once done for love."

This crisp line loops me back to Leaving Las Vegas, specifically to Cage's Oscar acceptance speech. When Jessica Lange reads his name, he kisses then-wife Patricia Arquette, briefly wrapping his fingers around the back of her neck. Costar Shue stands and whips her head back, prompting her section to rise to their feet. As if honoring the raw ingredients of a Michelin-starred dish, Cage begins by quoting the production's budget and use of 16mm stock. He thanks the Academy: "for helping me blur the line between art and commerce with this award. I know it's not hip to say it, but I just love acting, and I hope that there will be more encouragement for alternative movies where we can experiment and fast-forward into the future of acting." It's a credit to Cage's agility that he sees the line between film art and film industry as akin to a tensile high wire, a risky space for play.

Kael later writes of Brando, "His greatness is in a range that is too disturbing to be encompassed by regular movies." For Cage, too, even the most pedestrian titles seem to necessarily forgo their regularness once subject to his interventions. In her review of 2000's Gone in 60 Seconds, critic Antonia Quirke (author of the aptly titled lascivious cinema memoir, Choking on Marlon Brando) scoots past the film's incidental plotting to a haunting verdict on its star: "they stake out the cars they need to steal, and Cage gets to be Cage: the master of lyrical stupidity. It's a stupidity that passes so beautifully for sincerity, transmitted by a voice that hits the same three muffled-sax notes."

Faced with so suggestive a phrase, particularly one that stands to complicate critical consensus, my instinct is to parse. When is sincerity verifiably authentic? Under what conditions does stupidity exude lyricism? Does the effusive modifier "lyrical" absolve "stupidity" of its derogatory force, or indicate all we stand to miss by classifying "stupid" as strictly pejorative? Sincerity derives from the Latin sincerus: unadulterated, clean, pure; stupidity proceeds from stupere: to be amazed or stunned. Maybe what David Marchese refers to as Cage's occasionally "operatic sincerity" — a modality given to coming full circle, back to the irony it purports to reject — is actually lyrical stupidity, that which both plays to and signifies precisely the astonishment that film as a medium longs to capture, and film as a commercial industry puts at risk.

For a snapshot of what that looks like, I end with a film that postdates Quirke's appraisal — an unregular movie uniquely calibrated to the outer limits of greatness. In Panos Cosmatos's Mandy, we meet Cage's logger, Red Miller, expertly pressing the tongue of a chainsaw into an aged tree. A few seconds later, he and his crew are airlifted by helicopter from the site; a coworker proffers a beer and Cage shakes his head, telling us all we need to know: here is a man with self-imposed limits, the early disclosure of which is the film's promise that he'll transgress them.

Mandy is named for Red's wife, played by Andrea Riseborough, with whom Red lives in sweet seclusion until she's noticed on the roadside by the leader of a barbarous cult — then hunted, captured, drugged, propositioned, and set fire to before Red's eyes. The rest of the film attends Red's revenge: the acquisition of weapons, violations of physics. As in Cosmatos's earlier film, Beyond the Black Rainbow, the ambiance is that of a Christopher Pike paperback, hallucinatory and oversaturated, even as its core story — women: still vulnerable — is woefully, agelessly mundane.

There's always a scene that a film thinks is its most important. Here, it's Red breaking down in the bathroom. A wide shot taken from a false or cutout wall lends the cramped room an air of diorama. The camera's circumspection only stresses what's kinetic: rooting in the linen closet for a stashed vodka bottle, Cage chugs, pants, groans. Pours the firewater in his cuts and down his gullet. Slumped on the yellow shag toilet seat, he screams staccato like a thing being cranked to its full charge, whereupon he stops short. He sobs.

The intensity, the "emotional nakedness" — as Cage has put it — is plain. But equally virtuosic in their unguardedness are two instances of Cage just . . . looking. In the first, he hovers in the amber-lit entryway on arrival home from work. In the foreground, Mandy sits curled at her drafting table, concentrating so intently on her artwork that she's startled by her husband's voice. He moves in close to ask what she's drawing, and for seconds the moment hangs there, at ease in his contemplation. That's just, wow. Nothing else happens here; we watch him watching, endowing a body with its curiosity, its senses. Looking for longer than it takes to convey that that's all he's doing. Looking with eyes that haven't seen his wife all day.

The second moment is the film's true ending: not Red's progressive obliteration of his enemies, but a flashback to what we realize is the first time he ever laid eyes on Mandy, back when she was a stranger in a bar wearing the t-shirt he'll call his favorite. It's a simple moment: expressive color, a lush score, and a reverse shot that reveals Cage seated in his pick-up, bloodied and grinning maniacally at mere memory. Nic Cage the puppy; Nic Cage the wolf.

"I believe the universe does away with that which sits on a fence," he told the graduating class of 2001. To unambiguously love what Nicolas Cage does is to see what he sees: a sweep of opportunities, missed, seized, and beckoning, but all within his scope. And to find ourselves in the passenger seat, lucky enough to watch.

Film scholar and critic Veronica Fitzpatrick (@gutomako) is a 2021-2023 Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Modern Culture and Media and the Cogut Institute for the Humanities at Brown University. She's a coeditor of the journal World Picture and editor-at-large/podcast cohost at Bright Wall/Dark Room. She lives in Providence, RI.