Get in the Cage

I understand Nicolas Cage's professional life from Peggy Sue Got Married (Coppola, 1986) through his late-1990s success as an action star as a series of attempts to identify the genres and plots that would balance the actor's excesses.1 Or, in terms he would likely prefer, the actor's long 1990s comprised a sustained, self-conscious effort at fashioning a career. "Not only do I like to change characters," he remarked just prior to the release of Face/Off (Woo, 1997), "I also like to change the style of movie. I want to do everything. I want to have a career where I can look back when I'm in my 70s and say: 'Well, I did do everything.'"2

The experimentation yielded various solutions — the surrealism of Wild at Heart (Lynch, 1990), the melodrama of Leaving Las Vegas (Figgis, 1995), the lunatic violence of The Rock (Bay/Simpson/Bruckheimer-Buena Vista, 1996) that proved his action flick viability (an improbability after the disastrous Fire Birds (Green, 1990)). Meanwhile, he revised earlier missteps to find the right match between star and scenario, as when he inserted into Con Air (1997) the famous line "put the bunny back in the box," a reference to his "legendary" performance as Little Junior Brown in Kiss of Death (Schroeder, 1995).3 Where the brutal, asthmatic Brown, alternating between savage assaults and puffs on his bedazzled inhaler, seems to exist outside of and against Kiss's grim neo-noir sensibility, Con Air counterpoises Cage's long-haired, drawling Cameron Poe to the deranged cruelty of John Malkovich's Cyrus the Virus and the plane crash that helped demolish The Sands casino on the Las Vegas Strip.4 Miraculously, Con Air's consummate wackiness, the aesthetic equivalent of Three Stooges Syndrome, works.

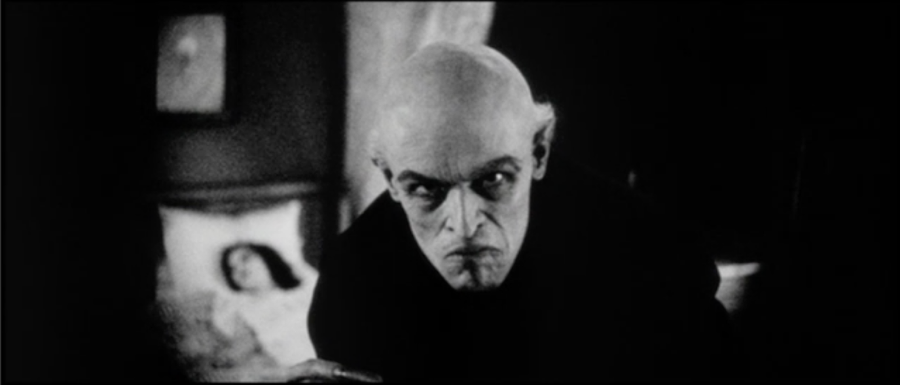

Again and again during this period, Cage invoked the vampire to bind the episodes of his acting life into the narrative of a career. Flourishes modeled on Max Schreck's titular ghoul in Nosferatu (Murnau, 1922) appear as early as Peggy Sue, where Cage performed the trademark claws-and-grimace while pursuing his unhappy girlfriend; at the end of Moonstruck (Jewison, 1987), he arrived at the Castorini house as a beatnik Dracula with love bites visible on both his and Loretta's necks.5 But it would be in Vampire's Kiss (Bierman, 1989) where the monster would become the emblem of his star persona. Playing Peter Loew, a yuppie literary agent who believes he has become a vampire following a tryst with a fanged Jennifer Beals, Cage committed the indelible act that crystalized his public image: eating a live cockroach on-screen. Mention of that incident became a journalistic convention in the years that followed, a shorthand acknowledgment of the actor's commitment to his roles as well as a sign of the strangeness of the man himself. Cage knew, or claimed in retrospect to have known, the method in his apparent madness: "I did that because I knew then that people would still be asking me about it now."6 Through the vampire, suspended between life and death, Cage could, as Manohla Dargis put it in 1995, remain poised between character and star: could keep in dynamic equilibrium his centrifugal impulse to take on every kind of project and dissolve into every kind of role, and his centripetal impulse to be "Nicolas Cage."7 While all stars perform their personae at the same time that they take on their character-roles, Cage treated this fact with a rare degree of explicitness and intensity.8 It is perhaps because of the vampiric gap — that eccentric character-actor Cage, as Dargis would have it, is not quite a star despite evident stardom, like the vampire is not quite alive despite its animation — that he succeeded so thoroughly in Face/Off, impersonating John Travolta's FBI agent Sean Archer impersonating Cage's terrorist Castor Troy. At any rate, Cage deemed his own performance successful because its outlandish expressiveness followed from his work in Vampire's Kiss: "I felt really proud of [Face/Off] because I was able to go back to what I had learned on Vampire's Kiss, which was sort of my experimental laboratory where I tried things out, facial expressions and attitudes."9

After inverting and ironizing the figure as Bringing out the Dead's Frank Pierce (Scorsese, 1999), a nocturnal paramedic harried by visions of the young woman he couldn't save, Cage seemed to be on the verge of exhausting the vampire's possibilities: a crossroads for his career. In interviews he flirted with a Jekyll-and-Hyde "one for them, one for me" route, proposing a split persona where he would keep "Nicolas Cage" for studio ventures like Gone in 60 Seconds while taking on riskier projects under the name "Miles Lovecraft," a moniker appropriate to the kind of jazz-horror concoctions he might pursue.10 That didn't happen. But, at the same time and more clandestinely, he experimented with another path that must have looked to him at the time as the culmination of a professional trajectory over a decade in the making. Like many of the bona fide stars of the era, he became a producer, hanging his Saturn Films shingle at Disney, which had distributed The Rock and Con Air.11 His first project was Shadow of the Vampire (2000), a property that had languished unmade for over a decade and which, as Variety's Braden Phillips aptly put it, Cage "raised . . . from the dead."12

Shadow of the Vampire presents the production of F. W. Murnau's Nosferatu with a metafictional twist: Max Schreck (Willem Dafoe) is an actual vampire. Murnau (John Malkovich) casts Schreck in a quixotic attempt to make a "completely authentic" fantasy, describing the "actor" to his crew as a student of Stanislavski who will never break character. Murnau offers starlet Greta Schröder (Catherine McCormack) to Schreck as a sacrifice in exchange for his participation. Antagonism between director and player amplifies throughout, as do parallels between them: Schreck attacks cast members and Murnau pushes forward, propelled by megalomania and laudanum. At story's end, Murnau photographs Schreck feasting on Greta and killing both producer Albin Grau (Udo Kier) and cameraman Fritz Arno Wagner (Cary Elwes), and then turns his lens on the vampire, exposing him to sunlight and causing him to sublimate in a puff of overheated celluloid.

If all movies made during what J. D. Connor has called Hollywood's neoclassical era (1970-2010) are "movie movies" — that is, works that allegorically "capture the interlocking agendas of their contributing authors" — then low-budget, metacinematic passion projects like Shadow of the Vampire, where control is distributed among fewer participants, should give rise to especially vivid figurations of those agendas.13 That's just what we find in Shadow of the Vampire. Three years after the movie wrapped, and freed from promotional responsibilities, screenwriter Steven Katz pulled no punches when disparaging Elias Merhige, whom Cage had chosen to direct after seeing his experimental feature Begotten (1990):14

The director, Elias Merhige, came out of doing experimental films and MTV stuff, and he has a very different approach to filmmaking than what I was used to. Elias didn't really know a lot about vampire movies or genre movies. He hadn't seen a lot of movies period, which was really shocking: though he's seen a lot of art films. We used to fight like hell when I'd say it was a vampire movie, and he'd say, 'No it's not.' So when they started shooting it, he and producer Nic Cage, with a lot of influence from John Malkovich who plays Murnau, shifted the thrust of the movie. I had originally wanted it to be just a really great vampire flick, the way The Godfather was just a great gangster movie. But they stripped away a lot of the layers of horror I had and made it sort of an art film about the nature of creativity and the relationship between the director and his film, which I had in the script, but as subtext only.15

Here, purposely or not, Katz explains his conflict with Merhige in terms drawn from the movie he disliked; in his grumbling, director, producer, and star merge into Murnau who, maniacally committed to a theory of realism, triumphs over true vampire Schreck at the cost of the vampire's nonlife, a fitting analog to Katz's forsaken genre film screenplay. While promoting Shadow, Katz transformed that subtext into an interpretation of that original screenplay, emphasizing the parallel between monster and modernist artist:

One of my real targets is how we raise artists up on a pedestal, when most of them, outside of their craft, are real sons of bitches . . . You can look at a dictatorial director like Erich von Stroheim, [or writers and artists like] Ezra Pound, [T.S.] Eliot, [Edgar] Degas — these are extraordinary artists who are desperately awful human beings. How much is it worth to make a good movie? It's something I ask myself every time I sit down to start a new script.16

Just as Katz bombastically equated his own work with Coppola's, here he implicitly indicts Merhige as a modernist epigone, the kind of veiled insult one might expect from a Columbia English M.A. who, at the time, had no screen credits to his name.

Merhige, for his part, unabashedly embraced his modernist sensibility, discussing the film's cataclysmic conclusion in terms that acknowledge an explicit investment in the protocols of his medium. "Murnau is now, y'know, in this sort of orgasmic frenzy," he says of Shadow's ending,

where the camera has sort of demonically taken on its own sort of automation, where this mechanical god is now manipulating Murnau. The eye of its lens is glowing . . . We took a blowtorch to the actual negative . . . the negative [which] is this vampire, this symbol of the cinema itself . . . it reduces its subject to a mere shadow. It takes its flesh and blood away and reduces it to a shadow that will and haunt us forever.17

Implicitly riffing on André Bazin's influential paired observations of the photographic camera's automatism and of cinema as "change mummified," Merhige figures Murnau as the modernist artist in extremis.18 So committed is Nosferatu's director to creating a work based on the specific ontological properties of his artform that he has given himself over to the medium and to the apparatus. Murnau's figurative self-immolation before his god reaches its completion in the literal immolation of the film itself; Merhige gets to see Murnau's work to its logical conclusion, culminating in homage to nitrocellulose stock's famous flammability.

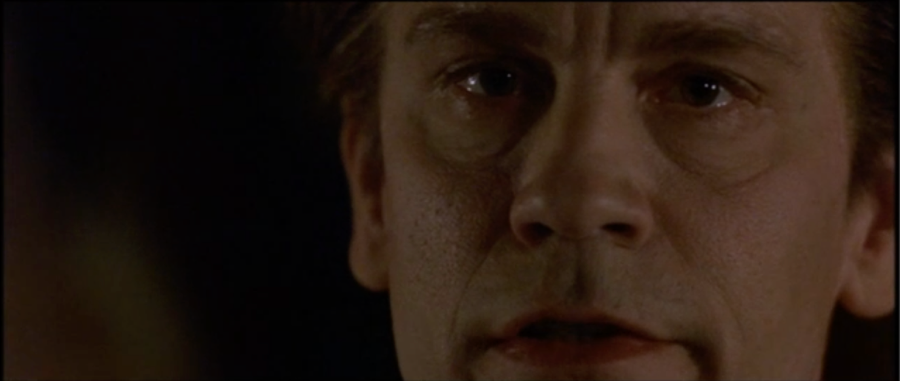

At odds — Katz with his commitment to low genre pitted against Merhige's high modernist aesthetics — the sensibilities of screenwriter and director converge at a crucial moment just past Shadow's midpoint. As Grau and scenarist Henrik Galeen trade drinks of schnapps at the foot of a campfire, kibitzing to cope with the increasingly fraught production, Schreck appears out of the darkness; emboldened by booze, they ask him to assess "the technical merits" of Bram Stoker's Dracula, testing, they believe, the extent of the actor's preparation. Schreck's explanation, initially taken to "miss the point" of the novel, ultimately persuades them with the depth of his identification with his character. Merhige: "This is a scene when I first read Steven Katz's script that I just thought was absolutely something so special and so wonderful that I really wanted to do it justice on the screen" (49:38-49:55). Schreck explains that Dracula "made him sad" because the Count had no servants for four hundred years, but he nonetheless must convince Jonathan Harker that he is a man: "can he even remember how to buy bread? To select cheese and wine? . . . the loneliest part of the book comes when the man accidentally sees Dracula setting his table." What Galeen and Grau construe as a virtuoso elaboration of a fictional backstory — Schreck preparing his character — is in fact a description of Schreck's own inability to remember what it meant to live like a man. What the scenarist and producer construe as a display of acting from emotion memory — the means, according to Stanislavski, of investing a role with vitality — is, for Schreck, the ironic opposite: the confession of painful, shameful forgetting that accompanies having no life at all.

Acting as a vampire and being a vampire, for the moment juxtaposed to both humorous and poignant effects, collapse into each other as Schreck grabs a bat from the air, bites its head off, and sucks its blood. Merhige, immodestly: "this is probably one of the great, great moments of any movie that I've seen" (52:37-52:40). The ostensibly thespian gesture, the commitment to actorly artifice ("Schreck, the German theater needs you!" Galeen exclaims) is ultimately indistinguishable from eating, among the most fundamental and instinctual of actions. Character and person, comedy and pathos, Katz's commitment to genre conventions (sucking blood) and Merhige's commitment to a modernist elaboration of the features of an artform (acting): all oppositions dissolve amid the astonishing act. Whether Schreck is a man or a monster, in either case his performance for his audience is remarkable.

Unlike the vampire he plays, Dafoe practiced no version of the Method, instead devising his behavior from the outside in, conforming his performance to the makeup and corset that constrained his movements and enabled his embodiment of the character. But in appearance — the grim, determined, ashamed-and-blissful face, framed in close-up — Dafoe-as-Schreck is, in this moment, an homage to Cage's cockroach snack (Dafoe's Schreck follows his bat with a swig of Grau's schnapps; Cage cleared the bug guts from his mouth with vodka). For a fleeting moment, Shadow of the Vampiretransmutes its off-camera conflicts and on-camera ontological confusions into a single image in order to transcend them, and it's both appropriate and telling that that image should be Cage-haunted.

Appropriate and telling because Shadow of the Vampire proposes a new solution to Cage's then-career-long problem of imbalance between performance and context by removing himself from the literal picture and dismissing the problem entirely. That solution manifests at the start of Shadow's mesmerizing conclusion, when Murnau tells his doppelganger Schreck "if it's not in frame, it doesn't exist." The merging of person and performance, story and backstory that Schreck's bat-eating indicated is here exaggerated and transformed in Murnau's wish to obliterate all the world that isn't part of the authentic horror movie, the real fiction, that he's made. But Murnau isn't the invisible artist-god he would be for the simple reason that he continues to appear in the movie in which he unwittingly stars. Nosferatu and Shadow have not become the same movie, and Murnau and Schreck have not become the same monster; they face each other framed in not-quite-matching closeups, one in orthochromatic black and white, the other in color, suggesting their mutual movement toward the asymptote of identification. But they merge only outside the world of the film in the image of their vampire-producer, refined out existence but imbuing each performance with caginess, his horrible fingernails likely unpared.

***

Two years after Shadow of the Vampire received its acclaim — two Academy Award nominations, for Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Dafoe) and Best Makeup — Cage explained that Saturn Films presented an opportunity to continue his film career without necessarily being in them. "Maybe I should take more time in between parts," he told interviewer Michael Fleming. "[I]t might not be a bad thing for me to have a company where I can go to the office and make phone calls and meet people that are interesting, to try and find projects for other people to do. That way I don't have to constantly be acting [in] back-to-back [projects]."19 At the time, Cage had no inkling of the squeeze he'd feel at the end of the decade from his reckless spending and a $6.2 million back-taxes bill. The Nicolas Cage of today acts more than ever, and with some frequency playing a version of himself; Tom Gormican's The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent, a movie starring Cage playing Cage reprising past roles, is set for release in April 2022.

Fittingly, his conception of his career has changed; that is, he no longer maintains a belief in a career at all. In a 2019 New York Times interview, Cage told David Marchese:

There's this old sci-fi movie called "Quatermass and the Pit." In the movie, someone says to Professor Quatermass, "Do you ever find your early career catching up with you?" And he says, "I never had a career, only work." I feel like that's where I'm at now. I never had a career, only work. I'm just going to keep working.20

With the fiction of a career forsworn, the vampire figure, with its atavistic, aristocratic valance, no longer fits; he hasn't played one in decades.21 But given his compulsive recapitulation of his star-self for a paycheck, can a zombie Cage — a turn as the unglamorous proletarian undead — be long in coming?22

Jordan Brower (@jordanrbrower) is an assistant professor of English at the University of Kentucky, where he teaches film and media studies. He is completing a manuscript about Classical Hollywood and American literary modernism, provisionally titled Hollywood Signs: A Literary History of the Studio System.

References

- Thanks to cluster editors Devin Daniels and Kim Andrews, for inviting this submission and reading multiple drafts; Post45 editor Dan Sinykin, for asking the right questions; and Aaron Pratt and Andrew Willson, i migliori Cagofili.[⤒]

- Jamie Portman, "Hot Actor: Nicolas Cage Makes No Apologies for Action Roles," The Record (Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario), June 5, 1997.[⤒]

- Legendary, according to David Denby; quoted in Manohla Dargis, "Method and Madness," Sight and Sound, June 1, 1995: 7.[⤒]

- Little Junior Brown updates the grinning and giggling hoodlum Tommy Udo (Richard Widmark) in Henry Hathaway's original semi-documentary noir Kiss of Death (1947). As a murderous psychopath, Udo fits squarely among post-World War II "tales of abnorm," a tendency that drew on American anxieties about maladjusted returning veterans and resonated with worries about returns to economic, institutional, and geopolitical stability. Udo thus fits the film perfectly as the deviant who must be eliminated so that protagonist Nick Bianco (Victor Mature), a former criminal, can settle down with his new wife and live "every day the same as every other day." Cage's Brown, on the other hand, is merely strange: hence Dargis's accurate description of the character as a "hodgepodge of interesting bits of business." Dargis, p. 8. On "tales of abnorm," see Richard Maltby, "Film Noir: The Politics of the Maladjusted Text," Journal of American Studies 18, no. 1 (April 1984): 49-71.[⤒]

- Vampire's Kiss [⤒]

- "That was the symptom of beginning acting at 17 . . . I heard all these incredible stories about Brando and thought 'Well, I guess you have to sort of generate those stories.' And I worked at it. I knew it would get around. Even eating the cockroach in "Vampire's Kiss" — I did that because I knew then that people would still be asking me about it now." Claudia Puig, "He's Up. He's Down. He's Up. He's Down. He's Up for Good?" LA Times, February 4, 1996. See also, e.g., Lawrence Grobel, "Out There with Nicolas Cage," Movieline May 1996, p 43: "Q: How come you didn't make it a fake cockroach? A: Because I knew you and I would be sitting and talking about it 10 years later"; "Nicolas Cage: Action Hero," Good Morning America, June 2, 1997: "Elizabeth Vargas: The live cockroach? Nicolas Cage: The Interesting thing about that is we're still talking about it fifteen years later."[⤒]

- Dargis, "Method," 7. In her pamphlet National Treasure. Nicolas Cage, Lucy Gibb calls this "Caginess" (17).[⤒]

- That merging of persona and self is nowhere more evident than in the assumed surname Cage, which, in deriving from a Marvel hero (Luke Cage), attests to his acute consciousness of his fantasy of self-making (to distinguish himself from uncle Francis Ford Coppola).[⤒]

- Grobel, "The Good Times of Nicolas Cage," 1998.[⤒]

- David Lynch called Cage "the jazz musician of actors" after directing him in Wild at Heart. "He's looking for complicated notes in his acting. And if you don't channel him or ride herd on him, it could become frightening music." Carla Hall, "The Wild and Weird Nicolas Cage," The Washington Post August 31, 1990, p. d01. On "Miles Lovecraft," see Amy Wallace, "His Truth is Out There," Chicago Tribune (November 12, 2000). [⤒]

- See, for example, Tom King, "Big Stars Work the 'Vanity Deal,'" The Wall Street Journal, June 2, 2000. J.D. Connor explains that the vanity production company and the first-look option — the kind arrangement Cage had with Disney/Buena Vista — constitutes Neoclassical Hollywood's "aestheticization" of Classical Hollywood's star system buttressed by the seven-year contract. See also: J. D. Connor, The Studios After the Studios: Neoclassical Hollywood, 1970-2010 (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 2014): 43. The routine allegorizing of film workers' understandings of film production in the movie's made during this period is discussed below.[⤒]

- Braden Phillips, "Steven Katz, Screenwriter," Variety, August 28, 2000.[⤒]

- Connor, Studios, 42-43, 12. [⤒]

- Cage received a VHS copy of Begotten from Crispin Glover. Jeff Simon, "Out of the Shadows Director Elias Merhige Emerges from Hollywood's Dungeon Bloodied but Unbowed," Buffalo News, January 21, 2001. [⤒]

- Chris C. Wehner, "Shadow of the Vampire: An Interview with Steven Katz," in Who Wrote That Movie: Screenwriting in Review: 2000-2002. Bloomington, IN: iUniversie, 2003, p. 34. Although Merhige suffers the brunt of the damage here, Cage doesn't escape unscathed; by taking the high-culture road and forsaking good old fashioned genre convention, his Vampire was a worse movie than it should have been — worse, from Katz's perspective, than it was written — and not up to the caliber of Cage's uncle Francis Ford Coppola's success in The Godfather. And although Katz deemed Coppola's Bram Stoker's Dracula a flawed film, "it was promising," where Shadow, paradoxically highfalutin and less complex than initially conceived, was "disappointing." Since Coppola could only achieve his vision for the film by firing his effects supervisors and hiring his son Roman, we might see Cage's decision to make Shadow of the Vampire as, among other things, an episode in a family saga. Where Dracula includes an early film exhibition as both a sign of modernity and as an emblem of Coppola's decision to limit himself, as far as possible, to techniques in use circa 1900, Shadow of the Vampire (as I'll suggest below), emphasizes cinematic astonishment based on commitment to performance, the hallmark of Cage's career to that point . . . a career that properly begins in 1983, the year he changed his surname and appeared in Francis's Rumble Fish.[⤒]

- Hugh Hart, "The Resurrection of the Undead," Los Angeles Times, December 21, 2000, F6.[⤒]

- Elias Merhige, Director's Commentary from Shadow of the Vampire, DVD, 1:23:48-1:24:41.[⤒]

- André Bazin, "The Ontology of the Photographic Image," What is Cinema 1, translated by Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967): 9-16.[⤒]

- Michael Fleming, "Before he was a $20 million action hero, Nicolas Cage was an actor's actor and world-class eccentric," Fade In Online (archived web page; May 13, 2008). [⤒]

- David Marchese, "Nicolas Cage on his legacy, his philosophy of acting and his metaphorical — and literal — search for the Holy Grail," New York Times, August 7 2019. [⤒]

- In 2018, Cage did, however, refer to himself as trying to "challenge Werner" in his portrayal of Terence McDonagh in Herzog's Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans (2019) by "being the California Klaus Kinski." Kinski, of course, played Count Dracula in Herzog's Nosferatu the Vampyre. In emulating Kinski, and thus in further mediating and aestheticizing his emulation of the German Expressionists, Cage perhaps found his way to post-tax penalty, late-career "Cage." And perhaps, in playing Red as the California Kinski at Panos Cosmatos's request in Mandy(2018), Cage defined the bounds of his decade of financial recuperation, before claiming to have given up on the idea of a career all together. Perhaps. I'm grateful to cluster editor Devin Daniels for bringing this interview to my attention. See:"Nicolas Cage Breaks Down his Most Iconic Characters," GQ, September 18, 2018. [⤒]

- Mark McGurl, "The Zombie Renaissance," N+1, no. 9 (Spring 2010): 171-172.[⤒]