Little Magazines

The house of knowledge is bookended by a poetics of death. In issue one of Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" (1984-1989), the reader learns of two such passings. The very first entry of the first issue of the magazine, published in May of 1984, entitled "HOW STRANGE TO BE GONE IN A MINUTE" is Stephen Rodefer's take on the loss of Ted Berrigan (1934-1983):

He did what he did, and there was no gain without say — for he was amused and alive; and all those vital or fatal humors were generally intelligent to a disarming degree, even when you didn't get it . . . Just yesterday I bought SO GOING AROUND CITIES in Lenox, Mass., signed "Ted Berrigan — on the premises." And so he was, and will be I imagine for a long time, just as he deserved.1

The second entry is written by Barry Lane for Hollis Frampton (1936-1984), concluding this first issue of the magazine. The final page of the issue houses a reminiscence of Frampton on the screen. It is followed by a stark low-fidelity, black-and-white reproduction of a still from Nostalgia (Frampton, 1971) on the inside of the back cover, stretching the contents to the limit of the interior. 2 The image is entirely burnt out in its electrostatic reproduction.

Hollis Frampton died last month. I found myself feeling a loss, yet I hardly knew him. Over the years I saw a few more of his films. They were unique and magical in a way that made you believe he could have made a million films, and still you'd have questions. I'll miss him like the ride you remember when you first hit the road, and someone picks you up and takes you a long way toward where you think you want to go.3

Like Frampton's films, Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" has taken me a long way further than I had thought I wanted to go, even when I didn't get it. The magazine was edited by Ben Friedlander and Andrew Schelling, "on the premises," from 1984 to 1989. A Bay Area bastion of (post?) L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poetics, Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" offered refuge for ongoing critical discourse as some of the formative journals of the movement concluded and new voices in experimental poetics began to emerge. Here is the "Editor's Note" to the final issue, on the demise of the magazine:

This is the last regular issue of Jimmy & Lucy's. It has been a group effort, many people have helped — contributors willing to write articles on the strange things we suggest, readers with inquiries, praise and imprecations. Copies of the magazine always seemed to travel hand to hand, enjoying themselves in places and in ways we couldn't imagine . . . This is not a last testament though. Mainly it's a chance to rethink the labor intensive, almost paleolithic technology we've used to produce the magazine. House of "K" will probably reappear in days to come. When it does it will happen irregularly, unexpectedly, perhaps in a different format, likely as not under some alias.4

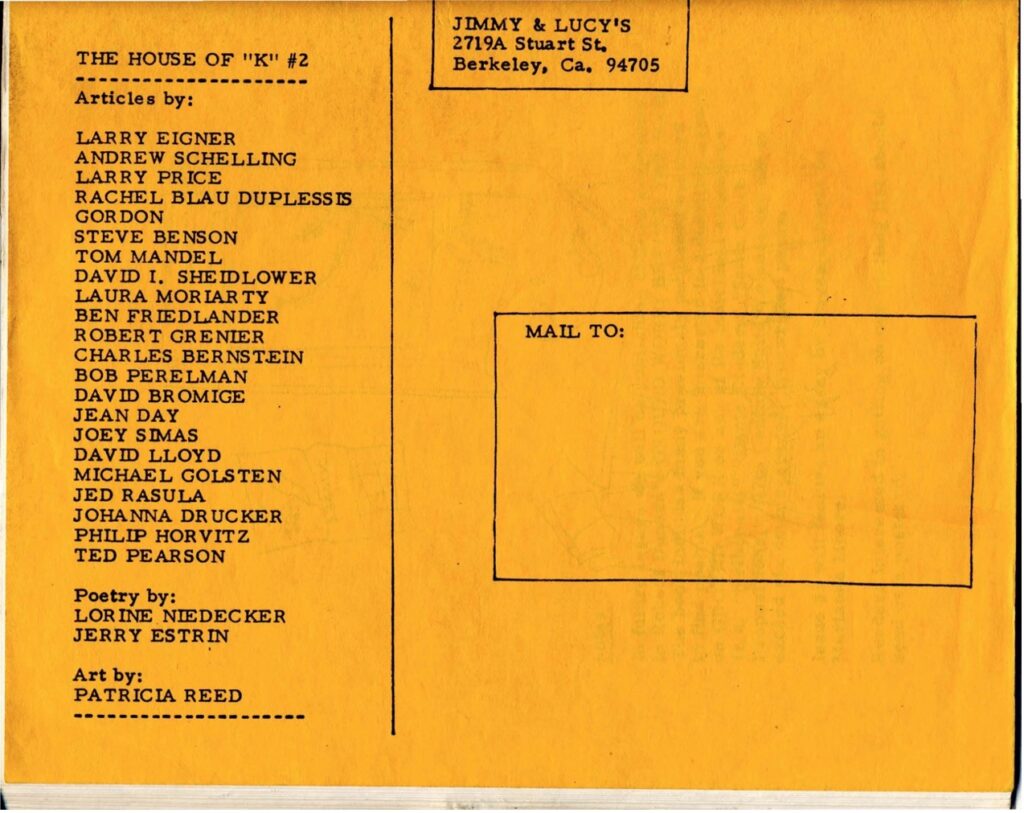

The magazine's probable and unexpected reappearance "in a different format" (in this case, as a set of digital files) nearly forty years later is the subject of my contribution to this Post45 cluster. Before tracing a trajectory to the strange afterlife that finds these copies "enjoying themselves" online, first, a note on the intensive labors of its original production. The "paleolithic technology" noted here, as Schelling describes it for the From A Secret Location website, was anchored by "an old IBM Executive typewriter, huge heavy machinery, its keys badly worn."5 The variable spacing of the typewriter mirrors the variable editing tactics beyond the type: "Exacto knives, white-out, and rubber cement." These paste-ups were then photocopied and side-stapled at a local copy center. From these hand-crafted limited productions (variable in number, estimated around 50 per issue), the magazine passed "hand to hand" through localized circuits not unlike the filter bubbles of social media posts or the intimate bureaucracies of networked art.6 Amplified by the postal design on the back cover of the first two issues, Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" was designed for mobility.

Unsent by the postal office, this particular copy finally found transmission via digital scan.7 By design, the magazine is configured as a mobile home, parked temporarily in various locations. Removed from the circulation that defines a periodical, however, the magazine changes, it becomes indexed, archived, unmoored. While the material texts of distribution remain, the function of the magazine shifts to something between a scattered (or highly redundant) collection and a public (or multiply authored) correspondence — too produced to be read as informal letters among friends, too contingent to be read as an anthology. In advance of getting into this unimagined reformatting, we might restart with scanning and once more with an archive. Even now, using that word — archive — continues to echo, for me, Craig Dworkin's defining statements on Eclipse in the article "Hypermnesia" from 2009: "the digital files that constitute the archive — that constitute any digital archive — are a set of little fetishes against forgetting."8 Then again, on loss, channeling Jacques Derrida: "the archive is a depository of loss, a crypt of expenditures which can never be accessed or deaccessioned."9 Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" has taken me places I did not expect to go. From a scanning experience in 2004 to a conference lecture in 2012 to my scholarly practice in 2022, I've spent nearly two decades thinking about a magazine founded in the year I was born (1984). At that, a diaristic anecdote:

On the conclusion of my freshman year of college in New Jersey, I was introduced to Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" as an ideal summer project to digitize by my mentor Craig Dworkin for the newly-created Eclipse archive. I was thoroughly honored to ferry these mysterious booklets—aged by rusting side-staples and weathered pages, made singular through their typographic irregularities and ink splotches — to my home for the summer in rural Utah. I had a plan: to use my father's "advanced" state office scanner to digitize these works, despite our growing estrangement after a year away. Not only was I returning home to Utah after a transformative period on the east coast, I was returning with purpose to decipher and make public these talismanic artifacts to which I had been entrusted.

All this to say, I owe much to the magazine, not just in terms of form and content, but also in the specific encounters, material instantiations, and contingent readings it has inspired in me variously over the past twenty years. As Abigail de Kosnik might have it, the "archival repertoire" of scanning these pages has both anticipated and programmed the professional work I've pursued over the past decade.10 In the summer of 2004, I was mystified by Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K." I recognized no names, caught no references, knew none of the debates, did not comprehend the interpersonal dynamics, nor did I grasp this magazine's relation to poetry proper, especially given the openly experimental format its poetics essays took in both form and content. The excitement in stumbling upon (and through) the magazine — a rarity, an enigma, a vibrant forum — was a formative experience (and remains so). Moving through its pages in the intervening years has been an estranging pleasure, an ongoing experience of loss. A little fetish against forgetting:

I had never spent so much time in my father's office. Hours passed. Counter to his conventionally efficacious time management, he was somehow content to observe me in the rhythmic process of scanning, as each spread of the magazine embraced the languorous mechanical line of light on the platen. We listened to the slow drawl of the scanner alongside an "underground" internet radio station, long after the Utah State Office of Education had closed for the evening. It felt mildly illicit. It was the nearest to my scholarly practice that we'd ever had a chance to play at together. The nearest we'd ever have a chance to do. My father died this past year, unexpectedly, in the spring of 2021. I've often thought back to these moments, working late in his office digitizing this magazine long before digital copies were the norm. In this way, despite the pervasive availability of small press print, the circulating scans of Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" remain, for me, an adjacent or tangential scan of loss. Unlike the lossy compression of the GIF or JPEG, this distortion was captured ambiently, off-screen, in the light that dispersed beyond the confines of a TIFF file. A reminder of both a time and a person now beyond all technologies of capture.

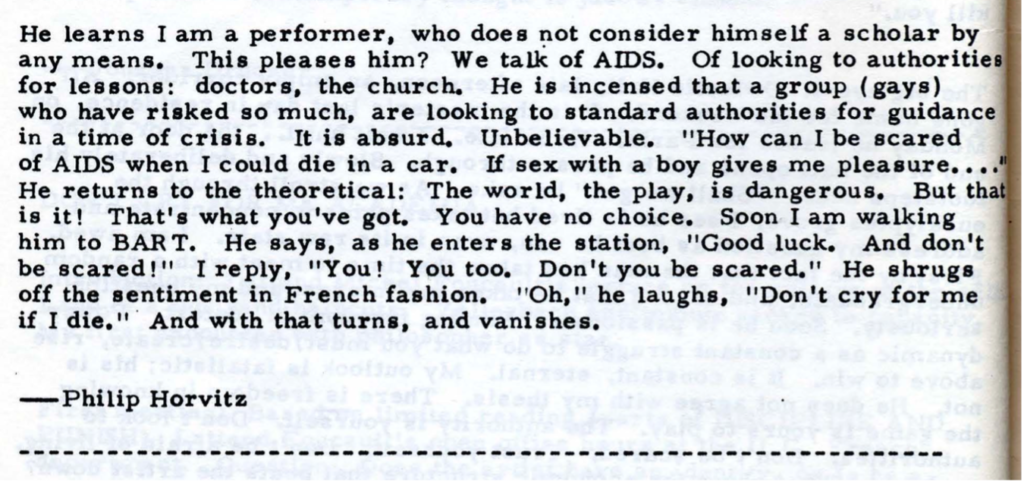

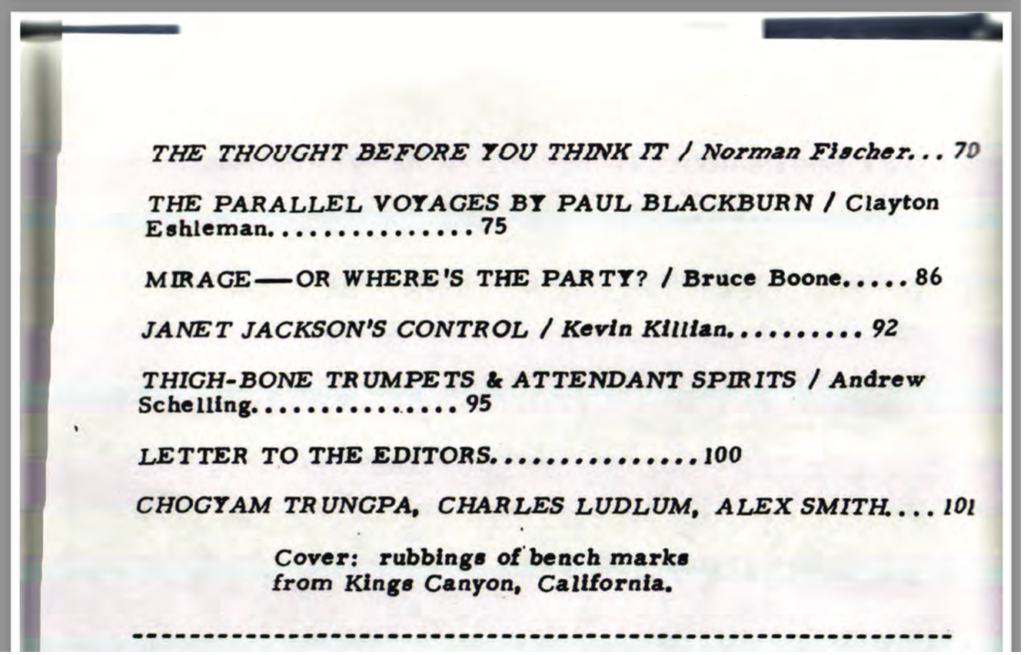

As the first issue opened with Berrigan's death and ended with Frampton's, the following two issues of Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" each followed suit: both featuring two deaths per issue. In issue two, Johanna Drucker's insightful reading of the importance the work of Michel Foucault (1926-1984) precedes Philip Horvitz's haunting poetic recollections of encounters with Foucault at Berkeley (see below).11 Then, the death of George Oppen (1908-1984) is marked poetically by Ted Pearson's citation from Daedalus: "He believed more in the things / Than I, and less. Familiar as speech, / The family tongue."12 Issue three keeps track with two more deaths. Eschewing new obituary formats, it instead excerpts from texts to recognize the passing of both François Truffaut (1932-1984) and Viktor Shklovsky (1893-1984), exhibiting the transmedial impulses of a poetics journal mourning film and theory alongside its generic progenitors throughout its pages. In each, a heterogeneity of forms emerges: poetic fragments, memories, essays, excerpts, blown-out images. These elegiac features anticipate any magazine's necrology, defined by a parenthetical lifespan only after it has passed: (1984-1989).

I first presented on the magazine as a grad student at "The Poetry of the 1980s Conference" held by the University of Maine in Orono in the summer of 2012. I had given my talk the title "Relocating Jimmy & Lucy's House of 'K'" in a play on its new "home" online. The presentation was accompanied by a download link to the full set of digitized files, a first public airing of my amateur nighttime scans from 2004. It is strange to return, differently, to thoughts from that time that have otherwise remained unpublished. Perhaps it was apt to do the kind of work that mirrors the ephemerality of the periodicals themselves: scholarship bound to the moment of its live delivery and local context. It was in collaboration with James Hoff that I first began to think of the lecture as a kind of "multiple" in homage to the happenstance printed matter delivered alongside art installation or performance practice.13 Now, as I'm writing for publication over a decade later, I find I still want the writing to echo a kind of live dispersion of forms and formats. Rereading the style of this moment in the '80s — the density of references, the citational bricolage, the unrepentant parataxis —inspires awe despite its having fallen out of fashion for poetics communiqués, even when informal, as in a social media post, or in a short collection like these hosted by Post45. At Orono, I read the following statement:

Inspired by the work in Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" and precursors like L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, I have been drawn to compressed formats for poetic articulation. I've been engaged in an exploration of the public presentation as a kind of envelope, package, or game comprised by a variety of compressed generic formats. This presentation is nested within a series of such formats: including lecture and anecdote; citation and inventory; fiction and distribution. Tabbing through these modes of address, as one might navigate, say, an internet browser or PowerPoint file, opens a way to begin reading objects within the database. Moreover, though these probes or explorations remain brief paratextual engagements, about the average length of blog posts or status updates, this should quickly be cataloged as an effort for fidelity to the magazine. I'd like to prepare a highly mediated reading of Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" — not as the nine side-stapled Xerox artifacts, published between 1984 and 1989, which I'd nevertheless like to pass around the room — but as a set of digital images, scanned as JPG files at 300dpi and converted into nine corresponding PDF files, published online today. Moreover, from this present vantage it becomes increasingly important to note how these technological effects shape the wider body of social text that facilitates the practice of poetics today.

Relocating. How is a magazine like a game? Might magazines also warrant an interpretive strategy from the perspective of a contingent first-person present, disoriented and on-the-move? Video game scholar Laine Nooney describes their methodas a kind of "speleology," (in homage to Foucault's The Archeology of Knowledge) grasping at dark twisty passages as one might explore a colossal cave.14 This rhymes with my experience of what's most magical about navigating Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K." An object not unlike the "oldest house" in the action-RPG Control (Remedy, 2019): bigger on the inside with sharp shifting architectures, unlikely connections, unseemly passings. To "play" the magazine, the reader must wander, drift, spelunk. Rather than perform a targeted or tactical close reading of representative segments or oft-cited moments first published in the magazine — like Susan Howe's statement for the New Poetics Colloquium or Robert Duncan's revisions and additions to "The Homosexual and Society" or Kevin Killian's "Janet Jackson's Control" (the list could go on for some time: the contents are astounding) — I'm drawn instead to play a reading of the magazine that preserves, as much as possible, the disorienting heterogeneity of the periodical, the weird and the unwieldy. Holding historical layers, incommensurate encounters, and the mysteries of the serial document in tension with (my) lived experience. De Kosnik, drawing from Diana Taylor, grounds this auto-archival impulse in the embodied repertoires that anchor her monograph Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom (2016):

But something strange happens when one investigates both the built and metaphorical instances of "archive" in the digital age. The closer one comes to "archive," the more scrutiny one devotes to it, the larger another, seemingly opposite, idea looms: the idea of "repertoire." The reader who begins this book thinking that she will learn all about "archive" in the digital era will finish the book realizing that she has, in fact, been reading intensively about "repertoire." For every actual and virtual archive in the digital age depends heavily on repertoire, and can even be said to rely more on repertoire — by which I mean physical, bodily acts of repetition, of human performance — than seems readily apparent.15

Repertoires. As is well known, "magazine" etymologically stems from the goods "storehouse" or military "warehouse." Here, then, is a ramshackle house of "K," the single letter stand-in for a possibly Foucauldian concept of "knowledge." It amplifies the material ambiguity or formal potentiality of a letter, like any unit of meaning. Isolated, perhaps, as a call-back to that immediately preceding poetics magazine spelling the word "language" in a laborious letter-by-letter equivalence. To return: if this magazine declares itself a kind of house, it is most certainly a mobile home. Like the racing cart featured on the cover to issue number six, published in May of 1986, the magazine is on the move.16 With so few copies produced, where might we locate the magazine today? As of this writing, there are precisely 53 results for a Google search for the phrase "Jimmy and Lucy's House of K." By replacing the word "and" with an ampersand, Google returns about 698 results. This is misleading. After scrolling through 50 entries to the bottom of the page, Google changes its mind, giving you "Page 2 of about 92 results." The remaining 606 are presumably duplicate references and sales pages — noise in the algorithm. Toward the bottom of the page, my 2012 talk, "Relocating Jimmy & Lucy's House of 'K'", as syndicated in the conference program, is indexed among the legitimate hits. In this context, the number of entries for booksellers and aggregators vastly outnumbers the original production numbers. The longer that back issues of Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" remain unsold, the more variously and diversely their entries become reduplicated. Each typically goes for around 40 or 50 dollars, in decent condition. Here's a representative example, long since disappeared:

Jimmy & Lucy's House of K / #2, August 1984 With typed letter, signed by Andrew Schelling to Lew Ellingham, Schelling, Andrew & Benjamin Friedlander, editors. Bookseller: G.F. Wilkinson Books (San Francisco, CA, U.S.A.). Price: US$ 50.00. Shipping: US$ 3.50. Binding: Soft. Condition: Fine. Description: 81 pp.; 8vo; original stapled, illus. orange wrappers; half-page t.l.s. from Schelling, "Dear Lewis, Sorry I didn't get a copy of the magazine to you more promptly. Issue #1 is temporarily out of print, so here is #2. Among the more interesting pieces are Bromige's, the Eigner shard of autobiography, and for the more adventuresome the David Lloyd review of J. H. Prynne," with two more paragraphs regarding a contribution by Ellingham of "ch. 18," presumably of his "Spicer Circle" work. Articles by: Larry Eigner, Larry Price, Rachel Blau Duplessis, (Nada) Gordon, Steve Benson, Tom Mandell, David Sheidlower, Laura Moriarty, Robert Grenier, Bob Perelman, David Bromige, Jean Day, Joey Sima, David Lloyd, Michael Golston, Jed Rasula, Johanna Drucker, Philip Horvitz, Ted Pearson. Poetry by: Lorine Niedecker, Jerry Estrin. Art by Patricia Reed. Bookseller Inventory # 1148

Formally, one wonders if an essay might instead be comprised of bookseller annotations: an art of radical compression coupled with readerly enticements and the informatic specificities of the material text. (If not here, perhaps best seen in the archival poetic practices of Mark Francis Johnson.17) The bookseller listing is as good a sample as any — the full contents and interiors can be skimmed or browsed at leisure at Eclipse, so I won't deviate from the essay with further inventories — as the breadth, scope, and historical range of work published should, in any case, be immediately apparent. All the more reason to wonder why these fragments should remain among the most detailed searchable accounts of the magazine on the internet. The Bancroft Library at Berkeley secured the "manuscripts, paste-ups, and master copies" alongside "editor's notes, correspondence, unpublished manuscripts, subscriptions, flyers, and financial matters" of Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K." 18 Yet no real information is transmitted online. Beyond top hits for Eclipse, Granary Books, and Berkeley, the other links yield a predictable array of: 1) bio notes for editors Schelling and Friedlander; 2) bibliographic entries or appearances on the CVs of authors published; 3) lists of magazines that formed and circulated language poetry in encyclopedia entries; and 4) footnotes to critical articles (the most cited works from the magazine remain Horovitz's recollection above, Susan Howe's New Poetics Colloquium statement, Charles Bernstein's "The Kiwi Bird in the Kiwi Tree," and Duncan's "The Homosexual and Society"). Nanna Bonde Thylstrup outlines this condition in her book The Politics of Mass Digitization (2019):

As a matter of practice, something is clearly changing in the conversion of bounded — and scarce — historical material into ubiquitous ephemeral data. In addition to the technical aspects of digitization, mass digitization is also changing the political territory of cultural memory objects. Global commercial platforms are increasingly administering and operating their scanning activities in favor of the digital content they reap from the national "data tombs" of museums and libraries and the feedback loops these generate. This integration of commercial platforms into the otherwise primarily public institutional set-up of cultural memory has produced a reconfiguration of the political landscape of cultural memory from the traditional symbolic politics of scarcity, sovereignty, and cultural capital to the late-sovereign infrapolitics of standardization and subversion.19

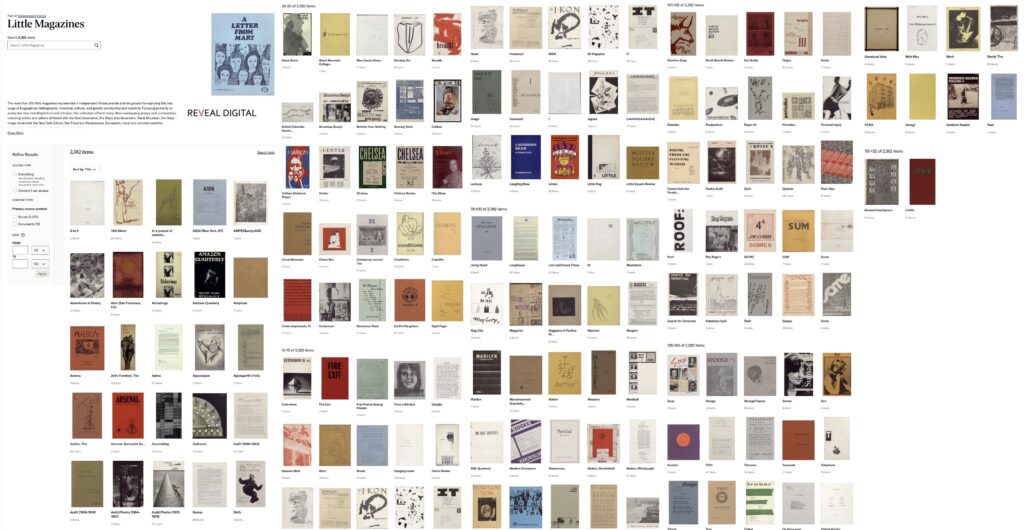

For Thylstrup, these late-sovereign infrapolitics pit the standardization of platforms like Google Books and Europeana against the "subversion" of what we might call "rogue archives" like Eclipse or "shadow libraries" like Sci-Hub and Libgen. Between these, we might locate the emerging middle ground in repositories like "Independent Voices," a Reveal Digital project now hosted by JSTOR that sources over 1,000 little magazines and alternative newspapers drawn from the special collections of dozens of major universities.20 This open access (for now) collection already features the full run of hundreds of magazines not unlike Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," ranging from 0 to 9 (1967-1969)to Zeitgeist (1965-1969). Like music and moving images, the presumption of access has become the norm — just another channel or service requiring subscription. In the rare case in which a magazine is not available online, there are librarians ready to help, with institutional support, specialized equipment, data standards, and professional training. In lockstep, the amateur repertoires of enthusiast scanning and fugitive distribution have been slowly dying out.

Like other regions of the internet, the little magazine's house of knowledge is built continuously more uniform but also more accessible, more regulated but also more accurate, less weird but also less scattered. The values of these shifts remain unresolvable, as do the inherent problems of centralized corporate-academic repositories, as risk-averse and proprietary systems lock down the circulation of cultural memory objects even while making them "free" and "open." Just as the labor of the "almost paleolithic technology" signaled the demise of Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," so too, in the always-on era of streaming content, goes the labor-intensive repertoires of maintenance and care guiding the amateur digital archivist.

As a student, I was taught that one doesn't choose the image that pierces you. The capture above, nested in the grey border of my MacOS Preview app taken moments before writing this line, blurs on my eyes. It features the conclusion to the contents of Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K" issue number 8 (Jan. 1988), which was repaired for the 2020 release of the full magazine on Eclipse.21 Distorted, the irregular type stretching and collapsing, the edges of the page blurring out of focus, the LED scanner's misplaced RGB values create a colorful spectra upon the image, which is itself cut off by the white margins introduced due to askew lines of type in the OCR process. It is a failed scan, the product of some slight incidental movement of the hand made worse by a low-grade office scanner from 2004. Then, just above the page, a sliver of black backdrop: my father's darkened office, vanishing, incidentally captured and poorly cropped. A fitting bookend, an image to burn, a little fetish, a periodical home in passing.

Danny Snelson is a writer, editor, and archivist working as an Assistant Professor in the Departments of English and Design Media Arts at UCLA. His online editorial work can be found on PennSound, Eclipse, Jacket2, and the EPC. See also: dss-edit.com.

References

- Stephen Rodefer, "HOW STRANGE TO BE GONE IN A MINUTE," Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 1 (May 1984). Throughout this essay, magazine references and image excerpts are linked to the specific page of their mention in the Eclipse image edition, which we released in 2020. Full PDFs are also available on the site: http://eclipsearchive.org/projects/K/[⤒]

- Back cover interior, Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 1 (May 1984). [⤒]

- Barry Lane, "HOLLIS FRAMPTON, 1936-1984," Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 1 (May 1984). [⤒]

- Benjamin Friedlander and Andrew Schelling, "EDITOR'S NOTE," Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 9 (January 1989).[⤒]

- Andrew Schelling, "Jimmy & Lucy's House of 'K,'" From a Secret Location (January 2017).[⤒]

- Craig Saper, Networked Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001), x-xv.[⤒]

- Back cover, Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 2 (August 1984).[⤒]

- Craig Dworkin, "Hypermnesia," boundary 2 36, no. 3 (2009): 83.[⤒]

- Dworkin, "Hypermnesia," 95.[⤒]

- Abigail de Kosnik, Rogue Archives: Digital Cultural Memory and Media Fandom, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 53-56.[⤒]

- Johanna Drucker, "MICHEL FOUCAULT, 1926-1984," and Philip Horvitz, "DON'T CRY FOR ME ACADEMIA," Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 2 (August 1984). [⤒]

- Ted Pearson, "IN MEMORIAM," Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 2 (August 1984).[⤒]

- See James Hoff and Danny Snelson, Inventory Arousal (London: Architectural Association/ Bedford Press, 2011). [⤒]

- Laine Nooney, "A Pedestal, A Table, A Love Letter: Archaeologies of Gender in Videogame History," Game Studies, 12, no. 2 (2013). [⤒]

- De Kosnik, 6.[⤒]

- Loughran O'Conner, Front Cover, Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 6 (May 1986).[⤒]

- See, for example, Mark Francis Johnson, Treatise on Luck (Brooklyn, NY: Gauss PDF, 2017). The ever-resourceful Johnson, it should be noted, was instrumental in the Eclipse release of the magazine in 2020.[⤒]

- UC Berkeley, Bancroft Library, Jimmy & Lucy's house of "K" records, 1984-1993. [⤒]

- Nanna Bonde Thylstrup, The Politics of Mass Digitization (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2018), 5.[⤒]

- Reveal Digital/JSTOR, Independent Voices. Accessed May 21, 2023.[⤒]

- Contents, Jimmy & Lucy's House of "K," no. 8 (January 1988).[⤒]