Little Magazines

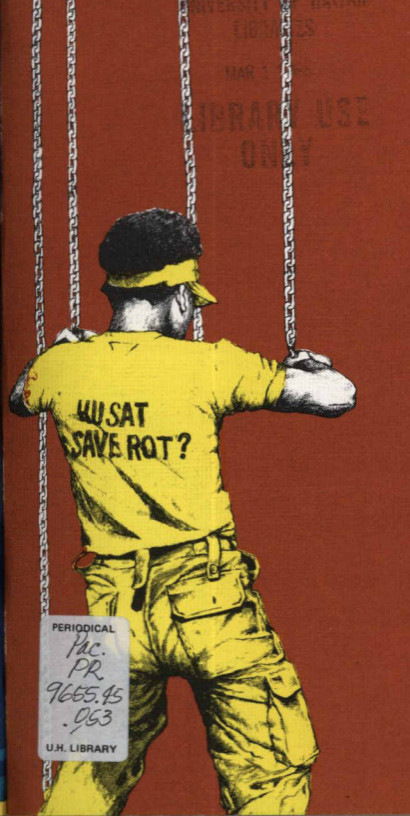

On the cover of a 1984 issue of Ondobondo, a male figure turns his back to readers, his gaze fixed on the chains in his hands. Dressed all in yellow, from his boxy cargo pants and t-shirt to the visor over his eyes, the illustrated man is framed by chain links that hang vertically from above. Though readers cannot see his face, the question on the back of his t-shirt seems directed to them: "Husat save rot?" — "Who knows the way?" in Tok Pisin (a form of Melanesian Pidgin English and the lingua franca of Papua New Guinea).2 3

Beside the figure is a poem in English: "Dancing yet to the Dim Dim's Beat" by Vincent Warakai. The poem laments that while Papua New Guinea (PNG) is now a sovereign nation, its people are still undermined by colonial influence. They continue to dance to the beat of the flat drums of the "dim dim," or white man: "We are dancing / Yes, but without leaping / For the fetters of dominance / still persist."4

Ondobondo was a short-lived literary magazine, running twice a year from 1982 to 1987, and like so many postcolonial artistic endeavors in the wake of independence, it took up the task of defining a newly independent nation's literature. Seeking to shake off the vestiges of colonial culture and assert a unifying, authentic voice, the magazine served as a cradle for local creative writing in a developing literary print culture. In the inaugural issue, the editors introduce the magazine by saying that they hope to expand in subsequent issues to include pieces "representative of writers from all parts of Papua New Guinea" and to create a periodical that is "fresh without being light weight, original without being clever, Melanesian without looking like every other literary magazine in this part of the world."5 Given the sheer diversity of the former colony, with over 800 languages spoken across its mainland and 600 offshore islands, the stated mission to represent "all parts" of PNG is more aspirational than actionable, but it also articulates Ondobondo's distinctly national focus.6

Steven Winduo, whose first published poem appeared in Ondobondo and who would later become a novelist and historiographer of PNG literature, explains that as a student writing for the magazine, he understood creative writing as "the project of imagining the nation." In an email interview, he writes, "Old residue of [the] colonial era was still felt and existed as mildew in the corridors of academia. The challenge was for the magazine to appeal to the confused sentiments being expressed and to maintain a flagship for positive growth through change."7

The magazine, edited by members of the Language and Literature Department at the University of PNG, was distinct from the generation of literary periodicals that preceded it in the 1970s in that there was little expat involvement. The journal is marked by a dense presence of visual artwork. Indeed, while previous literary magazines include ornamental decals alongside the texts or sections dedicated to ink drawings and material arts, Ondobondo is styled by illustrations that pair with the literary pieces. Students from the Visual Arts School read and then created interpretations of poems, plays, and stories, and sometimes multiple drawings from various artists appear on a single page alongside the text. 8

Through its blending of languages, the juxtaposition of English and Tok Pisin, and the use of local idioms such as, "dim dim," Ondobondo delineates its audience of PNG writers, artists, and readers. The incorporation of visual imagery into the prose and poetry also creates its own language and demonstrates how the publication imagines its community. The illustrations offer a visual narrative that echo and sometimes extend themes presented in the texts. For example, a poem by Elsie Mataio titled "Dok" ("dog" in Tok Pisin) depicts a starving dog scavenging "in a new suburbia."9 Mostly in English, the poem might be set in any place or time, except for its allusion to local flora with "orange kunai leaf." Goliath Yason's accompanying ink drawing accentuates the metaphor of poverty, showing a realistically styled dog hunched over a waste bin, a human expression of fatigue in its eyes that evokes Mataio's line "Dok walked lazily down." The poem fits in with the magazine's recurring themes of urbanization and economic hardship. Yason's drawing reiterates these themes but also offers translation and access for non-English readers.

As Pacific scholar Paul Sharrad explains, "the production and study of Pacific writing have been varied and marginal activities" and PNG writing holds an even more marginal space within that "small circle."10 Within the larger field of postcolonial and commonwealth studies, the novel dominates academic discussions. Yet, little magazines like Ondobondo, which are perhaps overlooked because of their ephemerality, capture the passing aesthetic experimentations and emerging styles of a new literary generation. As collaborative productions, periodicals encode the particularities of a time and place; the coterie of characters in their editorial teams, contributing writers, and influences and affiliations; and multiple voices and perspectives within their pages. Its ephemerality seems to give the little magazine less weight and consequence; yet, counterintuitively, its fleeting nature allows the journal to preserve not only the burgeoning literary imagination of the post-independence era but also the visual imagination not represented in novels and Pacific anthologies, which have tended to receive more critical attention.11

Polynesian and Melanesian societies share highly developed visual cultures, as seen in the emphasis and abundance of material arts, including tattooing, weaving, architectural design, rock painting, and wood carving.12 As Pacific writer-scholars Teresia Teaiwa and Albert Wendt have argued, the importance of the visual within Pacific cultures necessitates that "indigenous visual semiotics" serve as "a basis of indigenous literary criticism."13

While stories, plays, and poems would later appear in anthologies gathering literature from across the Pacific Islands, pieces from Ondobondo were republished as text alone without their original accompanying artwork.14 Stuart Dawrs points out that visuals are not merely supplemental but are an integral part of the literary pieces. Dawrs's thesis on the Ondobondo Poster Poems, a series created to be displayed during the 1980 South Pacific Festival of the Arts, is one of the few scholarly engagements with Ondobondo and PNG literary magazine publishing. Without the visuals, the anthologized poems are stripped of their context, and their audience is limited. Given low rates of literacy and high linguistic diversity in PNG, the artwork makes the literature more accessible to a wider public, creating a common language through visual idiom.

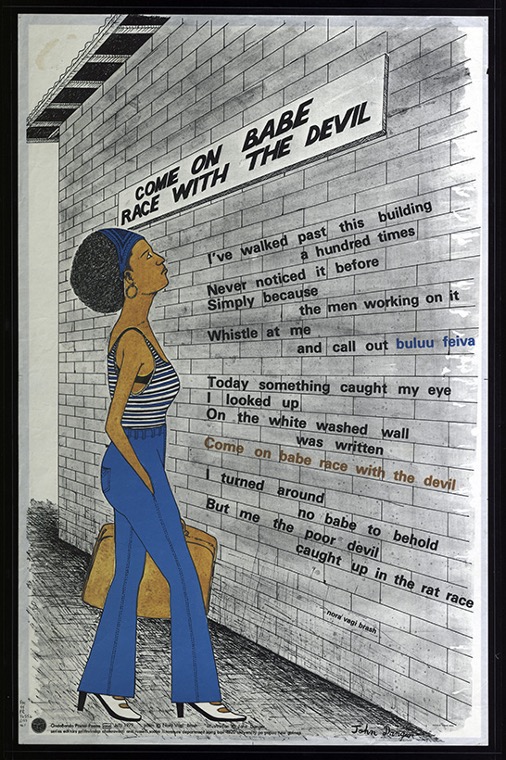

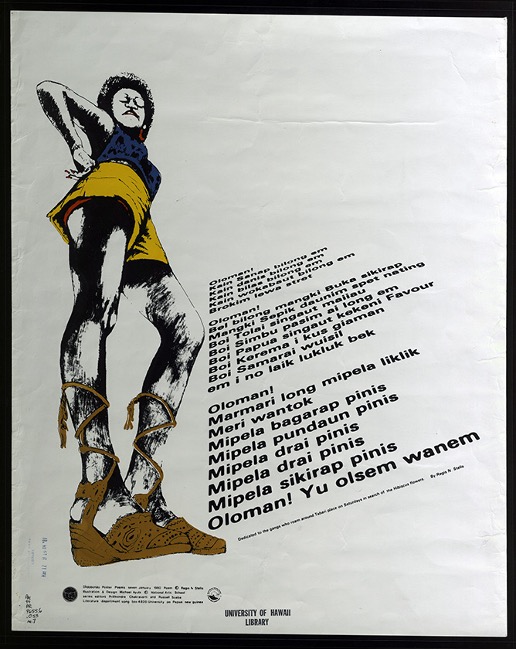

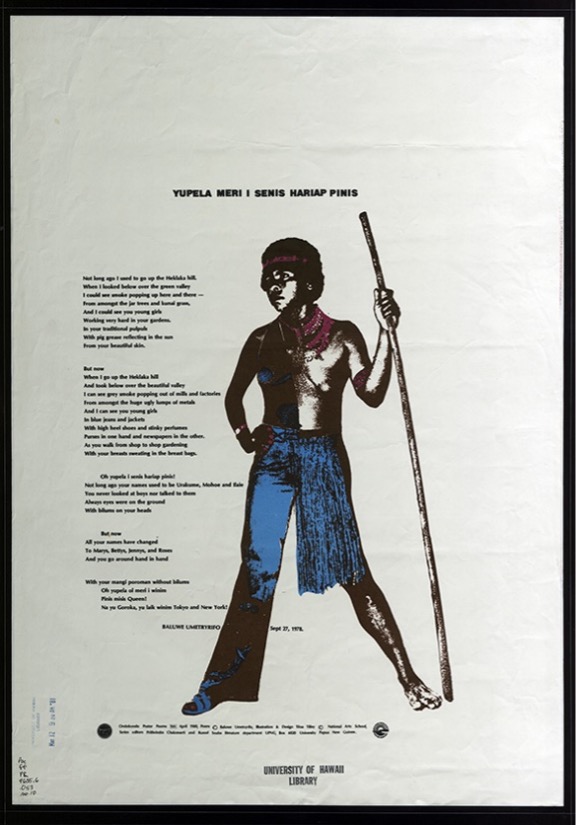

For Dawrs, the posters' artwork also documents a society in the midst of dramatic change and transition. For the most part, the women figures are represented as "modern, liberated figures."15 For example, the illustration accompanying Nora Vagi Brash's poem, "Come On Babe, Race with the Devil," shows a woman in jeans and high-heeled boots, her afro held back with a stylish kerchief (see Fig. 2).16 Another drawing shows a young woman wearing shorts, and the perspective of the drawing is angled so that she looks down on viewers "from a position of power" (see Fig. 3).17 The poster series and magazine represent characters during a time of rapid cultural shift. Fictional narrators and poetic speakers grapple with attempts to reclaim traditional roots and languages while working to thrive in a developing society. At the same time, the stark juxtaposition of images, the "modern" woman alongside the traditional one, presents a vision of the adaptivity and persistence of indigenous culture. Rather than seeking an impossible return to a pre-colonial past, characters are presented as living simultaneously in multiple worlds.

Ondobondo's Literary and Visual Aesthetics

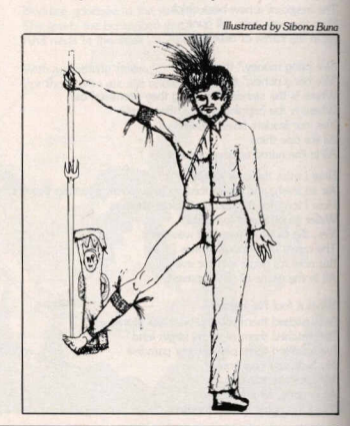

Unlike PNG literary magazines of the 1970s, like Kovave, which feature abstract indigenous iconography and woodblock prints, Ondobondo's artwork is overtly coded with its historical and social moment. Illustrations show realistic depictions of figures with '80s-style clothing and hairstyles. These are interspersed with figures in more traditional regalia worn in "singsings" or dances. In the interior of the mid-1984 issue, a drawing by Sibona Buna, who also created the cover illustration, depicts a man vertically divided: on his right side, he wears Western-style clothes, a button-up shirt and slacks, and on his left, he wears traditional arm and leg bands, a headpiece, and his arm is outstretched to grasp a cane or spear (see Fig. 4). The drawing represents a recurring theme across the magazine of individuals trapped between worlds. His hybridized body shows one foot literally in the world of industrial development and the other in indigenous tradition.18

In the first 1983 issue, a sampling of poems and accompanying drawings pick up on the recurring motif of captivity, pre-staging the chains on the cover of the '84 issue the following year. In the poem "Caught" by Sampson D. Ngwele, the speaker asks what he is doing "in the snare, stranded, caught, / Caught in a spider's web?"19 The embedded illustration by Bexy Moti shows silhouetted birds breaking through the strands of a web.

On the preceding page, the poem "Tied Up" by Joyce Kumbeli draws on a similar metaphor of entrapment. The speaker laments her family's economic woes. She cannot provide for her child: "no roof over his head / not a toea to educate him / or to buy him a shirt / to cover his bare chest."20 Joyce Kumbeli's poems re-appear regularly in Ondobondo, and like the works of other women contributors, such as Loujaya Kouza, Elsie Mataio, and Nori Vagi Brash, they often focus on domestic scenes and the gendered division of labor. In another poem, Kumbeli's speaker complains about the constant tyranny of housework: "endless chores staring at me."21 These spare poems are voiced by scrappy women speakers struggling to make ends meet, caught in the never-ending cycle of housekeeping.

Within the overdetermined landscape of nation-building literature, Kumbeli's poems offer a moment of personal expression and a different struggle for self-determination. While other works throughout Ondobondo, like Warakai's poem, deal with hybrid identity and the battle between colonizer and colonized, Kumbeli's poems of the "domestic sphere" allow for a more varied representation of voices and topics. Yet, the fact that pieces dealing with so-called "public" and "private" struggles appear side-by-side in the pages of the magazine creates a visual continuity between them. In other words, the magazine layout does not establish a gendered hierarchy in terms of its thematic subjects.

Confronting "Fatal Impact" Theory

The new national literature of PNG emerged from the university's literature department beginning in the mid-1960s, shortly after the institution was established. Leading up to formal independence from Australia in 1975, the curriculum of the literature department was deliberately developed with a de-colonizing agenda. The first cohort of creative writing students self-consciously penned what would be considered the first texts of the new nation. Yet, this pioneering endeavor was subject to outside impositions of ideas of "cultural authenticity." German-national Ulli Beier, who was brought to UPNG from his teaching post in Nigeria, played an integral role in shaping this new literature and established the first PNG literary magazine of its kind, Kovave.22 Beier emphasized the importance of folklore and assigned students to retrieve oral traditions from their home villages. According to Evelyn Ellerman, students had limited access to these traditional forms and "had to research the details by reading Margaret Mead and talking to village elders."23 Even more complicating were this European mentor's deceptive pedagogical practices: "he also masked his own identity to write, under the pseudonym 'Lovori,' the kind of folklore-based plays he hoped his students would eventually produce."24 Beier manufactured his own variety of authentic "native" literature to influence his students' writing. Beier was not the first PNG foreigner to don such a mask: the colonial administration's monthly newspaper The Papuan Villager evidenced similar examples of use of native pseudonyms.25 Though Beier's intentions were to foster a new decolonizing literature, his practices replicated those of the colonial administration.

Winduo discusses The Papuan Villager's project of cultural assimilation. He notes the irony that "Papua New Guinean contributors to The Papuan Villager could only write folklore, legends, and traditional stories — no longer than a paragraph or five lines or so."26 The prescriptive focus on folklore is continuous with the western anthropological gaze and fetishization of pre-contact indigenous culture. For Winduo, ethnography operates as a form of collecting: "Collecting — at least in the West, where time is generally thought to be linear and irreversible — implies a rescue of phenomena from inevitable historical decay or loss."27 This colonial view of fatal impact, which sees "native" culture as confined to a pre-contact past, imagines folklore as a relic from another time that has all but been extinguished by the advent of modernity.

While folklore and folklore-inspired pieces appear in the pages of Ondobondo, it is not the dominant focus of the magazine, and instead, the material is widely varied in its concerns and subjects. The motif of the divided figure, split between industrial development and indigenous tradition, which appears in Buna's illustration and in drawings featured in the Ondobondo Poster Poem series, depicts a stark conflict of identity (See Fig. 4 and 5). At the same time, it also shows traditional culture as alive and active in the present, not an irrelevant artifact of an outmoded past. The blending of text and image throughout Ondobondo also presents a hybrid form of new literature, which highlights the visual roots of traditional Pacific cultures while also exploring forms of expression in alphabetical language.

The illustrated man of the 1984 Ondobondo cover faces viewers with his back. In indigenous Pacific conceptions of time, voyagers face the future with their backs and gaze into the past.28 New Zealand poet Selina Marsh explains that this voyaging metaphor represents a deep engagement with history and the past that is necessary for shaping the future. As the man contemplates his dilemma, staring at the chains in his hands, listening to the flat drums of the dim dim's beat, the question printed on his back continues to ask readers, "Husat save rot?"

The image and the ephemeral magazine itself represent a transitional time in PNG's literary history, and yet, they preserve the energies and developing aesthetics that marked this moment of possibility. Ondobondo and the little magazines that came before it in the '70s create an important comparative framework when juxtaposed with colonial-era periodicals and newspapers, such as The Papuan Villager. They show the development of the first generation of a literary print culture in the years during and after independence, and they preserve the networked efforts, the collaborations between literary and visual arts, and the society of writers and poets on the scene during these years. Because of the collaborative nature of the little magazine, it offers a window into the sociologies of publishing in a time of immense political change, how editors and writers imagined their artistic community and the nation in responsive and urgent (indeed, ephemeral) ways that are not made explicit in novels and anthologies of the period. As a medium, the little magazine offers unique access into this past, capturing a moment when the question "Husat save rot" / "Who knows the way?" remains unsettled.

Marlo Starr is an assistant professor of English at Wittenberg University. A writer and interdisciplinary scholar, she specializes in contemporary poetry and postcolonial studies. She holds a PhD in English from Emory University and an MFA in Poetry at Johns Hopkins University.

References

- Ondobondo has been digitized and made available to the public through Athabasca University's virtual library, "Creating Literature in Papua New Guinea (1966-1986): The First Twenty Years," maintained by Evelyn Ellerman: http://png.athabascau.ca/Ondobondo.php. All images in this article are reproduced from Athabasca's website. According to Ellerman, the journals were never copyrighted or were copyrighted under colonial-era organizations that no longer exist. If you have an interest in these images, please contact me directly at starrm@wittenberg.edu.[⤒]

- Sibona Buna, Cover illustration, Ondobondo: A Papua New Guinea Literary Magazine, no. 4(mid-1984).[⤒]

- Special thanks to Papua New Guinea poet Michael Dom for confirming this translation of "Husat save rot?"[⤒]

- Vincent Warakai, "Dancing yet to the Dim Dim's Beat," Ondobondo: A Papua New Guinea Literary Magazine, no. 4(mid-1984): Cover. [⤒]

- Alan Chatterton and Ganga Powell, "Editorial," Ondobondo: A Papua New Guinea Literary Magazine, no. 1(1982): 1.[⤒]

- In contrast, Mana, which first appeared in the late '70s out of Fiji asOceania's first regional literary magazine, sought to express a pan-Pacific identity by culling writing from across the island nations.[⤒]

- Steven Winduo in email correspondence with the author, January 2022.[⤒]

- Two contemporaneous PNG periodicals also offer comparison with Ondobondo. Bikmaus (1980-87) published by the Institute of Papua New Guinea Studies, began as a combination magazine focused on essays and cultural criticism and then transitioned into a dedicated literary magazine later in the '80s. The PNG Writer, published by the Writers Union, first appeared in 1985. Both publications are much more text-focused than Ondobondo, which highlights the magazine's unique emphasis on visual imagery. The PNG Writer includes sketches and drawings throughout its issues but not with the same density and frequency as Ondobondo, and images are rare in Bikmaus.[⤒]

- Elsie Mataio, "Dok," Ondobondo: A Papua New Guinea Literary Magazine, no. 2 (1983): 24.[⤒]

- Paul Sharrad, "'Ghem Pona Wai?': Vernacular Imaginations in Contemporary Papua New Guinea Fiction" in Vernacular Worlds, Cosmopolitan Imagination, edited by. S. S. Karayanni and S. Stephanides (Brussels: Rodopi, 2015), 3.[⤒]

- Thanks to editor Nick Sturm for this observation. Though ephemerality is often presented as a weakness, perhaps this quality allows little magazines to capture experimentation and fluctuating aesthetics in a way not seen in more "permanent" mediums like the novel. [⤒]

- Teresia K. Teaiwa, "What Remains to Be Seen: Reclaiming the Visual Roots of Pacific Literature," PMLA 125, no. 3 (2010): 734.[⤒]

- Teaiwa, "What Remains to Be Seen," 735.[⤒]

- For example, Russell Soaba's poem "Looking Thru Those Eye Holes," which was originally featured in the Ondobondo Poster Poem series with artwork by Joseph Nalo, reappeared in the anthology Nuanua in 1995 as text alone. Stuart Dawrs, "Looking Thru Those Eyeholes: Re-Historicizing the OndoBondo Poster Poems" (MA thesis, University of Hawai'i, 2009), 34.[⤒]

- Dawrs, "Looking Thru Those Eyeholes," 37. [⤒]

- Dawrs, "Looking Thru Those Eyeholes," 37. [⤒]

- Dawrs, "Looking Thru Those Eyeholes," 38.[⤒]

- Sibona Buna, Illustration, Ondobondo: A Papua New Guinea Literary Magazine, no. 4(mid-1984): 18.[⤒]

- Sampson D. Ngwele, "Caught," Ondobondo: A Papua New Guinea Literary Magazine, no. 2 (1983): 26.[⤒]

- Joyce Kumbeli, "Tied Up," Ondobondo: A Papua New Guinea Literary Magazine, no. 2 (1983): 25.[⤒]

- Kumbeli, "Tied Up," 25.[⤒]

- I previously wrote on Beier's role in the development on PNG literature in "Little Magazines from across Island Networks," Asian Journal of African Studies 48 (2020): 55-81.[⤒]

- Evelyn Ellerman, "Learning to Be a Writer in Papua New Guinea," History of Intellectual Culture 8, no. 1 (2008/2009): 13.[⤒]

- Ellerman, "Learning to Be a Writer in Papua New Guinea," 7.[⤒]

- Ellerman, "Learning to Be a Writer in Papua New Guinea," 7.[⤒]

- Winduo, Transitions and Transformations: Literature, Politics, and Culture in Papua New Guinea (University of Papua New Guinea Press, 2013): 13.[⤒]

- Winduo, Transitions and Transformations, 11.[⤒]

- Selina Marsh, "Theory 'Versus' Pacific Islands Writing" in Inside Out: Literature, Cultural Politics, and Identity in the New Pacific, edited by. Vilsoni Hereniko and Rob Wilson (Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1999), 340.[⤒]