Little Magazines

Introduction

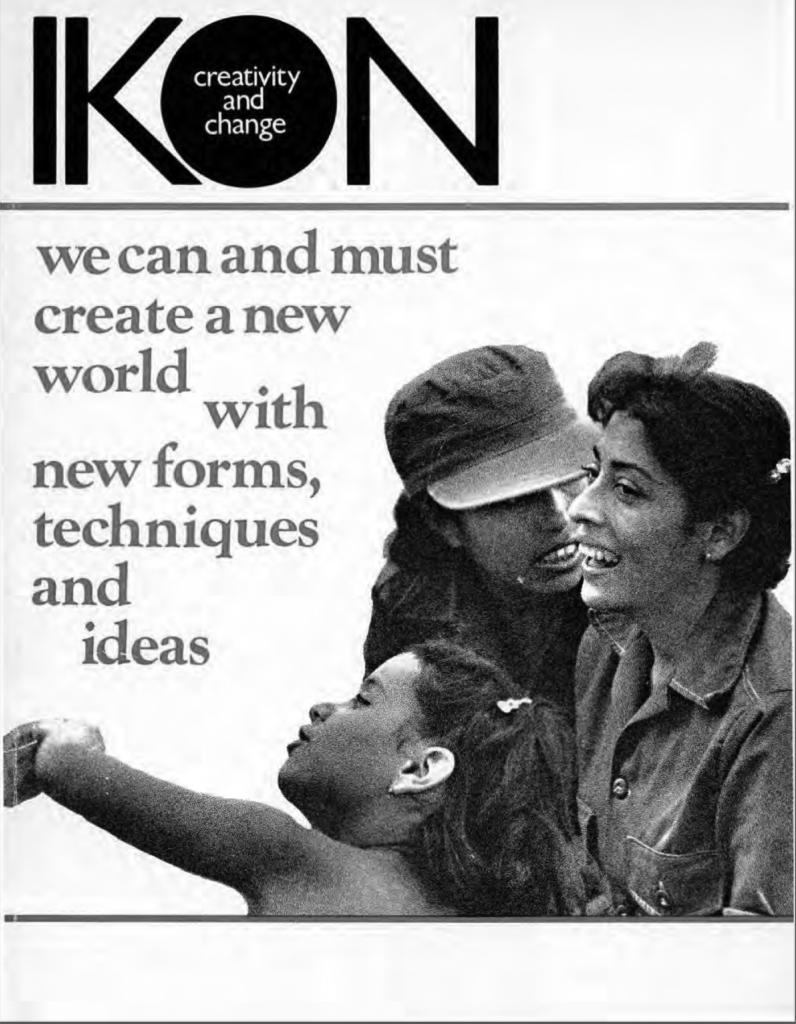

IKON was founded with the goal of synthesis, and part of its lasting value lies in the unique ways in which it accomplished that goal — and kept changing. The first series (1967-69), offset printed in a run of 8,000 with newsstand distribution and focused on art and politics, created a continuity with little magazine modernist predecessors like BLAST while also productively challenging prevalent images of '60s little magazines (and even our use of the "little" descriptor), the scholarship about which has tended to emphasize mimeograph and literary magazines with smaller print runs. But IKON was also very much a "little" magazine akin to its peers in other ways, including domestic production, lack of money, and censorship struggles: Susan Sherman, IKON's founding editor, describes how the production, which was done by her, artist Nancy Colin, and occasional volunteers, was housed entirely within her apartment; how the "political content" of the magazine matched her own investment in current events, leading up to the "turning point" of her attendance at the Cultural Congress of Havana; how the first series ended because the distributor refused to distribute the issue about the Cultural Congress.1 In this period, Sherman's friendship with Margaret Randall, who edited El Corno Emplumado / The Plumed Horn from Mexico City, is significant, as is IKONbooks, the countercultural bookstore and community event space, which operated in the East Village until 1971.

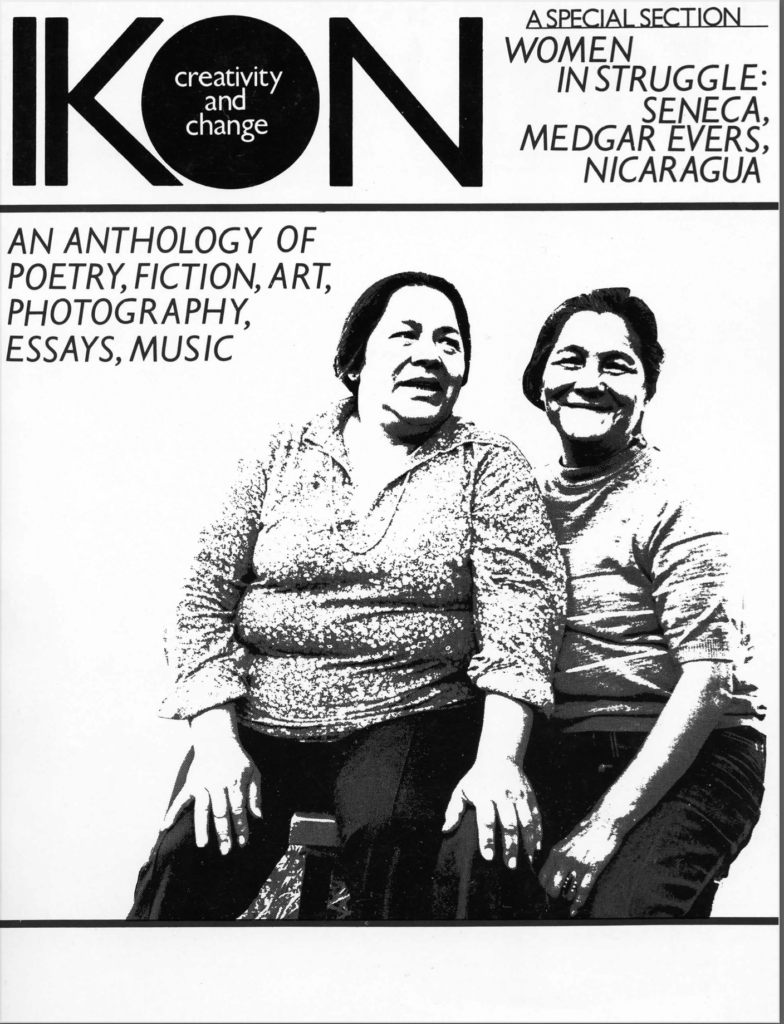

The second series, beginning in 1982, is larger in size with a smaller distribution, about 1,500. However, it extends and remixes the conversations begun in the first series, producing "anthologies" about once a year at the intersections of art and politics with issues like Women in Struggle and Art Against Apartheid. All of the second series, as well as Sherman's accompanying essay, can be found online at https://archives.worldlit.org/ikon-archives.html, and Sherman's memoir also contains a great deal of information about the context of the first series.2 Sherman has been a generous interlocutor, and the following interview is, like IKON, a project of repeated engagement and attention across different temporal moments: we corresponded over email in the fall of 2014, talked on Skype a year later, and then continued edits after transcription in early 2020 and in August 2022. Because the interview was conducted across different media, transcription involved slightly rearranging and condensing the material; some line edits were made for sentence clarity and consistency of punctuation. This interview is part of a larger collection of interviews with and resources about women active in small press publishing between the 1950s and '80s, Spies in the Audience, which is forthcoming with the University of New Mexico Press.

Susan Sherman

Editor, IKON (Series One 1967-69; Series Two 1982-94, New York City)

October to November 2014 and January 2020 via email and September 17, 2015 via Skype

Stephanie Anderson: The first series of IKON ran from 1967-69. Will you talk a little about the New York art scene during those years? What was the context for the journal, broadly speaking?

Susan Sherman: The New York Art Scene then was so vibrant, at the peak of artistic activity. For me personally, there were poetry readings at Les Deux Megots Coffehouse and then Le Metro, theater at the Hardware Poets Playhouse and La Mama Experimental Theatre Club. Going to the Living Theatre, avant-garde movies and on and on. However, the context for IKON was not only what was going on in New York, but my two trips to Cuba in 1968 and 1969 and my friendship with Margaret Randall who was publishing El Corno Emplumado in Mexico City at the time — both Cuban trips introduced me to people, material, I would never have had access to, drastically changing my relationship to activism as well as directly influencing the content and focus of the magazine.

SA: Let's talk a little bit about how the magazine started. In your essay about IKON for The Society for Educating Women's (SEW) conference that appears in the IKON Series 2 (1982-1994) archive,3 you talk about how you were originally supposed to be the book and theater critic for IKON Series 1, headed by Arthur Sainer and Thomas Muth.

You write, "After a year of meetings with no actual magazine, I finally said that I would make sure the magazine came out, but I had to be the editor. They agreed, and IKON was born." Had you had previous experience in publishing? Did it feel natural to take over as editor?

SS: Except for doing some chapbooks through Hardware Poets Theater and being on the school newspaper in high school — where I learned the technical as well as the journalistic parts of putting out a paper — I had no "formal" publishing experience. But then neither did probably 90% of the people involved in alternative media in the 1960s. I don't know what made me have the guts to announce I would take over the magazine. I somehow had the confidence I could — and in fact I did!! As far as I know, IKON is one of the only American alternative journals that had women in charge in 1967. By the time the second series of IKON came out in the early 1980s, I had a lot of experience producing a magazine, and a magazine run by women by then wasn't that unusual. I must say that the first series of IKON, pre-feminist movement, didn't have nearly enough representation in content by women, that took a lot of growing and learning on my part.

SA: You had already been in New York for what, maybe five or six years, when you started IKON?

SS: Yes, but even so it was a big step. To elaborate on what I said before, in the original meetings about publishing a magazine, nothing was getting done. I was tired of the endless meetings, and I didn't want to do the work and have others take credit for it, because I knew I would wind up doing all the technical work. And then finally after the first issue Arthur [Sainer] dropped out. There was no fight or anything, he just wasn't that interested. Tom [Muth] did get us $1500 to fund the first issue and was very supportive. We started IKON primarily because we were fed up with critics saying they were the ones who knew about art, not the artists who created it, and you had to depend on them to explain your work, and you couldn't talk about anyone you knew because you couldn't be objective. The magazine was always anti-Vietnam War but, of course, became more political as I became more politically involved. That's all detailed in my memoir, America's Child: A Woman's Journey Through the Radical Sixties.4 IKON became much more political after I returned from Cuba. And then Series One ended when we lost most of our distribution. I can't prove the government was responsible, but it was pretty obvious when we got the distributor's returns of the magazine I put together about the Cuban Cultural Congress I had attended. They hadn't even unpacked it. We depended on the money from the previous issue to fund the next one. And the next one was already in the printer. So that was the end of IKON Series One. Also 500 copies of the issue that I sent to Margaret Randall in Mexico never reached her at all.

SA: Yeah. That's crazy.

SS: Well, the best way to stop you was economically. You know, if they tried to do something more openly it might cause too much trouble for them. We also had problems years later with Lesbian material in the second series, with the NEA (National Endowment for the Arts). I mean, the way they can get you without causing a big fuss and having pickets and letters of protest is just to cut off your funding. We received no government funding at all for the first series.

We got NYSCA (New York State Council on the Arts) funding which paid for printing essentially and finally had gotten some funding from the National Endowment for the Arts for the second series. With the second series, IKON 9, the Asian/Asian-American women's issue, Without Ceremony [1988], I thought we were a shoo-in to renew the funding we had gotten from the NEA for the previous issue. It's a wonderful issue done in collaboration with the Asian Women United Collective who were the ones who gathered the material and did the design. They had already been working for some years collecting and putting together an anthology when they got in touch with us to see if we could help them complete the project. We helped put all the elements together and published it for them. It was only the second time another group had almost total control over the issue and its design — the first was the Art Against Apartheid issue — but the final reward was an incredible issue including everything from a sexuality roundtable, to a working mother's roundtable, to a veteran political activists' panel.

SA: It's great!

SS: I was really shocked when we were denied the funding, so I called the NEA, which you could do, and asked, "What happened?" The reply was "Well, the writing was uneven," which was crazy, it was a beautiful issue, you have it. The woman on the phone didn't know why specifically. She looked it up, and she only had an author's name, Huong Giang Nguyen. She happened to be the author of an essay titled, "The Vietnamese Lesbian Speaks." That's when I realized what had happened. During that period, the NEA was under heavy pressure not to fund any Lesbian and Gay material. Something they obviously didn't want to directly state, only using the author's name in their notes. Anyway, so that's what happened with the ninth issue, second series. It didn't stop us, but we were hoping to be able to fully fund the magazine and pay a little to ourselves, for all the work we put in. We always tried to pay the contributors and designers a little if possible. So I wound up funding a lot of the issues with my salary and my credit cards. I carried the interest on the debt for a long time and finally had to declare personal bankruptcy around 1997. It took me a long time to get my credit back. I don't know how I did it all, to tell you the truth, because I was working the whole time, at the equivalent of a full-time job.

SA: I think in the article you say that the circulation was around 8,000. Which was, you know, pretty impressive for a little magazine!

SS: That was only for the first series that was sold on the newsstands. The original IKON. The second series we distributed in bookstores. A much smaller run. Around 1,500. Except for the Art Against Apartheid issue which went into a second printing when the first printing sold out. Do you have copies of the original Series One IKON?

SA: Yes. [Stephanie shows her the magazines.]

SS: Well, then you can see that it was geared toward newsstands.

SA: The covers are very attractive in that way, very eye-catching.

SS: Nancy Colin, who was one of the co-founders of the magazine, was an artist, and the integration of graphics was one of the important points of the magazine, and although she left the magazine after Series One, the second series also integrated graphics and text. I mean, this was pre-Mac. I can't remember any other literary journals in 1967 that were doing that. The alternative news media, however, was very creative design-wise.

SA: Speaking of graphics and text, in the first series, the title IKON has a dot between I and KON. Was there a significance to this gesture? It makes me think of how the "I," the artist, can (kon?) "understand and write about" his or her own work.

SS: Actually, it had no significance. The dot between the I and the KON was just a choice by the people designing the first issue — probably Nancy. That is also why IKON was spelled with a K instead of a C. Purely because Nancy felt it looked better.

SA: That's a good enough reason! Continuing with the title, in the SEW Conference essay, you talk about its genesis: "For us the word IKON symbolized synthesis — words and pictures, art and politics, creativity and change, the separate parts fused as one into an organic unity in which all the parts could be perceived simultaneously, the way you perceive a picture. We believed there was no conflict between theory and art, art and action, that 'there was no place for the middleman,' that artists were perfectly capable of understanding and writing about their own work . . . " I love how this synthesis can really be felt in Nancy's design work.

SS: Actually the design of the magazine was the work of a number of people and varied from issue to issue. When everyone except Nancy left the magazine when I returned from Cuba, Nancy and I both did the layout as well as the design. Nancy left after the first series, and I did most of the design on the second series, along with a number of very talented women who helped. Remember it was almost all "volunteer." I and many of the others were not paid, and in the first series after the first issue, we supported the magazine with our own money and the money we got from sales and subscriptions. Because of the content of the magazine in the Sixties, government funding was out of the question.

After I got back from Cuba, the issues got even better graphically, because I learned a lot being in Cuba where they were doing amazing work design-wise with posters, films, and even their newspapers and magazines. My mother had actually gotten a scholarship — she never used it — in graphic arts, so maybe it's in my genes somewhere because I picked it up fast, and then later when I lost my job teaching, another result of my Cuba trip, I got a job typesetting and doing the graphics at a typesetting place at minimum wage, I might add.

And after that I got a job at Cooper Square Tenants Council doing bookkeeping I learned doing the books for IKON. So I learned all different kinds of skills because of experience on the magazine. But it was very hard. People don't understand how hard it was in the Sixties, they have this romanticized picture.

SA: So everything was really related organically. You write in the memoir, "These were not just pieces in a magazine. Each represented an activity in which we were either directly or indirectly engaged. The magazine was beginning to fulfill its initial intent in a way I had certainly never conceived of." Is that because you planned the content of the magazine to also symbolize synthesis?

SS: That really relates to the way the content of the magazine generated activity as well as being the result of activity. For example, my trip to Cuba which then became a causal factor of political activities I became in involved in and changed the way I looked at things and therefore my own art as well as the work that we published. We also tried to go outside set boundaries. For example, we also had, if you notice, tried to create a new tarot deck — this is pre-New Age, you know. I went to UC Berkeley where I first got involved with poetry and a lot of artists and poets in San Francisco were really into reading the tarot, and then there was Samuel Weiser's bookstore here in New York where you could buy a lot of great books. I still have a great library, lots on alchemy, the tarot, Jewish mysticism and other things. So one idea was to combine that with radical political activism. You know, to really put them together within the same context, like we did with the art work, and not have one in one corner and one in the other. That was one of the things I think that also made IKON different.

SA: It's similar to your initial kind of impulse behind the magazine, which was that serious theory and artists and critics don't necessarily need to be divorced — that artists are capable of commenting on their own work.

SS: Shouldn't be divorced. I originally met Arthur Seiner because I had been doing plays at the Hardware Poets Playhouse and La Mama and he gave me a really nice review of my first play. And he also wrote plays as well as being a critic. I started reviewing plays for The Village Voice when Michael Smith, who was one of the theater critics, went on vacation, and I took over for him, and saw like two plays a week for a long time. But once again the whole point was that we were sick and tired of critics, professional critics, saying that we weren't qualified to make "objective" judgments. Like, you know, unfortunately, although I like some things about Jung, this Jungian thing that there's the sensitive artist types and then there's the intellectual logical types — of course the women were the "sensitive types" who can't think objectively for themselves, and when the artist works that somehow your unconscious takes over and you don't know what you're doing! Because if you read Van Gogh's letters, for example — and many, many other artists, you know all of these artists were very involved in thinking about and critiquing their and other's work. I mean, we edit our work, don't we? We make choices all the time. I mean, a writer knows how to make choices! It's really very dangerous to think you have to depend on someone else to make the serious choices, both about your work and your life for that matter!!

SA: And so many writers I think do it as they're writing instead of afterward, or that the editing brain and the writing brain aren't as separate as people like to make them sound.

SS: Of course, you can do it as you're writing, or separately whatever. Even stream-of-consciousness — I bet Ulysses didn't just flow out of James Joyce. I'm sure he worked and worked and worked at it. And, please, that's not the same as controlling or manipulating your work to make it say what you want it to. Sometimes the words seem to take on a life of their own. The work is an expression of whatever you are. In a sense you are an instrument that the work flows through. But you're not an unconscious instrument. It's hard to explain. Everyone works differently.

So that was one thing. And at the time in the late '50s and early '60s the idea of the separation between critic and artist was really bad. I write that vignette in the memoir about how I was at Berkeley and they were talking about there was no more creative artistic work being done, that the critics were the creative people. At the very same time the San Francisco Renaissance was going on across the Bay. Which is very, you know, reminiscent of post-modernism, that somehow all the original work is over and you collage. Suddenly the critic becomes the philosopher-king. You know, that critics can not only tell us what art is about — it also means they'll tell you what you're allowed to produce, what's valid to produce. So that was really the main reason that we started the original IKON. And then because Nancy was involved, I think that's why the graphics became so involved. Working together. And there were also three different friends from Cooper Union working on the original magazine. I became very involved in the graphic aspects when everyone but Nancy left — I also painted a little bit on the side. I can show you a couple things I did.

SA: Nice!

SS: But, you know, we got the idea of putting these things together. Again that's where the meaning of the name IKON came from. Remember this was way before the computer representation of the word "icon." And not the religious version of it, but "icon" as a symbol in which, like a painting, you take in all of this information at once, not linearly. It's not separated out. So we started the magazine to try to bring these things together, and have artists . . . I remember the other thing was that artists weren't supposed to — and this is still true — critique friends. If you knew somebody you weren't allowed to write about them. And that was crazy because that would mean that I couldn't write about anybody I admired, because I knew so many people. But usually you pick out people that you feel simpatico with and why not write about them?

So it was for those two things. One, we wanted people to write about people that they knew and admired if they felt like it, like Yvonne Rainer's article about the dancer Deborah Hay who was her friend. People that were involved in the same groups. So that was the idea, because who would know better what somebody's work was like than somebody who was close to them. It was this whole phony sense of objectivity. So that's why we started IKON. A lot of that was Arthur Sainer's ideas too.

SA: I mean, it's also really just how a scene gets built, right, is the participants kind of reflecting on each other?

SS: Exactly. So that started it off. I knew Margaret Randall because she had published some of my poems in El Corno, much earlier though. I think maybe '63, '64. And she wrote a column from Mexico for the first issue. But that's how we got started, and then of course when the '80s came I started the second series. I had been writing Margaret about doing a magazine with her, but she was in Cuba — we had been together there at the Cultural Congress, and then Nicaragua — which made it very difficult [laughs] to correspond and work together. And I got this $5000 when my stepfather died and used that for seed money. So anyway, that was the genesis of the second series. Starting with Series One, IKON had obviously gotten progressively got more political. For the first series we refused to take any kind of funding from the government, as a matter of principal — not that we would have gotten it, since they were more intent on getting rid of the magazine than giving us money! Which actually represented to me that the counterculture — if you want to call it that, I mean, it's such a misnomer — was important, because at a certain point that's one of the first things they tried to defund.

SA: Speaking of genesis and funding, I was kind of curious about the things you were doing before and in-between the two series.

SS: Right. In grammar school I did a little cut-out magazine. I started reading in the first grade, like we all did then. Alphabet in Kindergarten, reading in grade one. But I was very sick that first year in school. You know, in those days they didn't have vaccinations for measles so the way you got vaccinated was that my sister had the measles and my mother put me in the room with my sister. It's very contagious. Because if you get it when you're five, or six years old, it's supposed to be not as deadly. The vaccinations now are certainly a much better idea!

SA: Yeah, the kind of chicken pox parties they used to have when I was a kid in the '80s.

SS: So I had chicken pox and I had measles. And I had scarlet fever.

SA: Wow.

SS: That was much more dangerous. They didn't do that on purpose! Or chickenpox either for that matter! So I was stuck in bed a lot. Of course with measles you can't read, because they're afraid it's going to get in your eyes, so you have to wear sunglasses and be in a darkened room. So I listened to records of stories. And I listened to the radio. That's probably where I got my love of science fiction, [listening to the radio dramas] X Minus One and 2000 Plus. But I did a lot of reading when I could, and I leapt way ahead with my reading. I just loved to read, so that's why when I was in the fifth grade as an art project I did my own magazine. I think that what gave me the most practical experience though was the high school newspaper I was on for two years. They actually had their own printing facility so what we would do is we would do the editorial work and then a preliminary paste up and then on Thursdays we would go to the print shop where they had a linotype machine, a big machine where one metal line of type is produced at a time.

People don't realize that the reason the type is justified (lined up) on both sides is because the old metal type actually fit in a form with wooden panels on the side which you put type into and locked it up, so it had to be straight on both sides and justified. First I was the third page editor and then the associate editor. So I edited the material, did the paste-up, and then went to the press for the final proofing, and actually laid it into the form myself. Then we took the proof and made a final paste up and put the page together. That gave me a huge amount of experience, including being able to read type backwards and upside down, which is what the metal looks like when you're standing over it until it's pressed onto the page — this was before offset printing.

SA: I do some letterpress printing . . .

SS: Well then you know what it is. So I already had that experience when I started doing the magazine.

SA: And then you were the poetry editor of The Village Voice very briefly.

SS: I also took over for Denise Levertov for a while choosing the poems for The Nation. And for the Voice it was the same thing. I chose poems and reviewed plays and some books. The Voice was quite small when I first started working there. They got much bigger when the newspapers went on strike, and there was no place for people to get classified ads except The Village Voice. Their circulation and number of pages shot up enormously during that time.

SA: I didn't know that, that's really interesting. I assumed it was a kind of protest literature increase.

SS: No, it was the newspaper strikes. I mean, the Voice was always well-regarded in terms of content. They had an office on Sheridan Square at the time. The poet Bob Nichols got me that job. He was married to Mary Nichols at the time who was one of the editors. Later he married Grace Paley. That's how I met her. He and Grace were involved with the Greenwich Village Peace Center, and I worked there at nights in the early Sixties selling peace buttons and generally just keeping it open. It was very quiet at night, and I wrote a lot of poems during that time.

SA: What was working on the little chapbooks with the Hardware Poets Playhouse and Hesperidian Press like?

SS: I worked on those with Allen Katzman, who edited a magazine out of the Judson Church called The Judson Review through his and his brother's press, Hesperidian Press. Besides my chapbook I have a copy of Jerry Bloedow's How to Write Poetry. Did you get that?

SA: I think I've seen that one actually . . .

SS: I have only one copy of my chapbook Areas of Silence. James Nagel did the drawings. I think we did one of his books. But just, you know, typed them. This is just cheap offset printing. It's pretty faded now.

SA: The issue that I sent you of The Hardware Poets Occasional is . . . I think it must be mimeo, but it's pretty hard to read at points.

SS: This is definitely offset. There was a little place on Eighth Street that used to do printing really cheap. You know they did just 8 ½ by 11 on a small offset printer. You could get, I don't know, 500 copies of one side of a page for like eight dollars or less. And we bound them ourselves — mine is an attempt to have a perfect binding (flat back cover). It didn't work out so well.

SA: Oh, I see.

SS: We only did four chapbooks. You know, we were having a lot of problems then, because around 1963, '64 the city tried to close down the poetry and experimental theater venues — we were doing the readings at Café Le Metro then — saying that we needed to have a liquor license to do poetry readings using an outdated cabaret law. Who knows the real reason. Whether they were trying to clean up the city, which was ridiculous, I mean these were hardly dens of iniquity. I mean, we smoked cigarettes and that was about it — there weren't any drugs or even alcohol around. We thought that it was commercial, because it was right before the World's Fair. We felt that it might be a conspiracy on the part of the people in the West Village, because at one point readings in the East Village and what was known as off-off Broadway theater were becoming very popular and taking customers away from commercial venues — I think the first reading I came to at Le Metro there was a line out the door that was over a hundred people.

And the plays — we had full houses at the plays. The theater venue I was associated with was the Hardware Poets Playhouse. You have one of the newsletters. It was uptown over a hardware store — hence the name! It was composed mostly of poets who read at Les Deux Mégots and then later Le Metro which were in the East Village. It was at the protests that I met Ellen Stewart from La Mama where I also did plays. They were very experimental. In fact, the full name is La Mama E.T.C. standing for experimental theatre club.

There's an interesting story most people don't know. Even though they might've used the term East Village once in a while, it became very popular because of the Voice ads and real estate interests. They couldn't rent property under the original name of the Lower East Side, because it reeked too much of immigrants, poor people, working people you know. So they coined this term the East Village to rent apartments. I knew that because I worked at the classified section of the Voice when Rose Ryan who was the head of the ads promoted the term.

SA: Was your bookstore, IKONbooks, in the East Village?

SS: Yes, it was a nice large open space next to La Mama. On 4th St. between First and Second Ave. That was the late Sixties, early Seventies where we did everything but sell a lot of books! We carried mostly alternative publications. We had poetry readings, music events and political talks, and one night a benefit for the Panthers. We supported it with our salaries and designing and printing the programs for La Mama. The rents weren't anything like now. If I remember correctly the rent was about $125 a month.

SA: And you put out an anthology of Vietnam War poetry . . .

SS: Actually, general protest poetry. It's called Only Humans with Songs to Sing. It was all done using an electronic stencil maker. We could put photos in and thin metal mimeo stencils would come out, and then we also had a Gestetner electronic mimeo. We actually mimeo'd the whole book. But I made the terrible mistake, because it looked nice, of using construction paper for the cover, and it's disintegrating. Like literally disintegrating. The ones I have, the construction paper is literally turning into dust. Newsprint is the same. I had a bunch of copies of the East Village Other in plastic protective sheets and you can't even take them out of the plastic.

SA: Yeah, that old acidic paper.

SS: On the other hand, we got all kinds of criticism from some movement people about IKON magazine supposedly looking too slick. It was work that made it look that good, not money. It didn't cost more except for using decent paper. We had a really good printer who printed on a huge press sixteen pages at a time. I remember walking into the deli on Second Ave. and the counter person saying, "Oh this is such a nice-looking magazine. Can I take a look at it?" I thought that it was such a disparaging kind of thing to think that somebody who was a worker wouldn't like something beautiful and well designed to look at. It attracted people's attention because it looked so nice! Just because you're doing a movement thing doesn't mean you should have to do it on newsprint — unless it's a newspaper, of course! — and make it look messy. I mean, even when we used the mimeograph — and we used it a lot — we tried to do it as nicely as possible. When I did Only Humans With Songs to Sing I just sat there all night with poems that were typed up and scissors, cutting out different little pieces of photos from magazines and newspapers to make designs for it.

SA: Do you think that doing projects like that — like that kind of anthology idea — is part of why the second series of IKON actually refers to itself as an anthology?

SS: No, the reason for that with the second series was that some of the issues were double issues and were anthologies. Also the issues only came out once or twice a year and were quite big, averaging around 130 pages. The double issues were larger. The ones we specifically called anthologies also had an ISBN number which you use for books and were sold both as magazines and books.

SA: Oh, okay, that makes sense.

SS: The Art Against Apartheid issue, for example — I hope you have that issue. That was the incredible issue that we did with the Art Against Apartheid committee with sponsorship from the UN. We also sponsored a reading around the issue.

SA: I have a copy from the library; I don't have a copy of my own.

SS: I only have about five copies myself. We went into a second printing on that issue. We didn't do much newsstand with the second series. The first series was almost purely newsstand which in a way was our downfall since we depended on three major distributors nationwide so after the Cuban issue, it was easy to cut us off. There was some bookstore distribution, but there weren't as many alternative bookstores. Now there're almost none. Even St. Mark's Bookstore, which is the last of them, is gone. So it was definitely mostly bookstore distribution for that second series — and then of course, much fewer magazines. I think we ran maybe 1500 copies. The Art Against Apartheid issue we did about 5000 because we went into a second printing; we sold out that first printing. And we had money from the UN, and a bunch of people contributed money to it. We were also getting funding then. Nobody got salaries, unfortunately, but as mentioned earlier, we got funding that covered printing from the NYSCA (New York State Council on the Arts Literature Committee), which then was being run by this wonderful gay man, Gregory Kolovakos, and for one issue from NEA, which is why it was such a shock when NEA didn't renew.

SA: Right!

SS: You know, you asked me awhile back what I was doing both before and after the first and second series of the magazine. I spoke a little about my trips to Cuba and their influence on me and on the first series of the magazine. After we stopped publishing the first series of IKON, and after IKONbooks — which closed mainly because it just got too hard to sustain both in terms of energy and money — I became much more involved in the Women's Movement and Gay Liberation Struggle, particularly in 1970 through the Fifth Street Women's Building, which combined Women's Liberation Movement and squatter action with Sagaris, an experiment in women's education. I travelled to Chile during Allende and Nicaragua during the early days of the Sandinistas in the Seventies and Eighties and continued to write and get jobs wherever I could find work — mostly low wage jobs doing things like typesetting — until I finally got an adjunct position teaching at Parsons School of Design, where I still teach. All of which contributed material, connections, and inspiration that led to revisiting IKON again in the Eighties.

Then in the early Eighties came IKON Series Two which followed pretty much the same philosophy as the first series except now it was consciously Feminist and exclusively published women with the exception of the Art Against Apartheid issue and the last issue that came out in 1994 and one essay by Henry Flynt in the first issue. Some of the issues were done in collaboration with groups such as the Art Against Apartheid issue, the Asian/Asian American Women's issue Without Ceremony, and the Coast to Coast: National Women Artists of Color issue. Even when the magazine stopped publishing, we still continued with a series of chapbooks by authors that included Hettie Jones, Harry Lewis, Ellen Aug Lytle, Chuck Wachtel, and later poetry books by Bruce Weber, Rochelle Ratner, Paul Pines, Gale Jackson. I had also done a series of chapbooks with Martha King between the two series of IKON.

SA: What do you think the value of reading IKON now is?

SS: First of all, as Audre Lorde so eloquently put it in "Poetry is Not a Luxury" — an essay that was really my inspiration to begin publishing IKON again — when she characterizes poetry "as illumination . . . The farthest external horizons of our hopes and fears . . . carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives." That is something without price and without age. IKON in both series is history, an archive, but it is more than that. As are magazines like Sinister Wisdom, which is still publishing, and Conditions, to name only two of many. All those many books and magazines are exemplars of the epigraph we put on the covers of IKON Second Series — "Creativity and Change." They should be preserved, and even more they should be read. They contain our history and aspirations more than any textbook ever could.

Notes: This interview has been edited — though sparingly — for clarity. As far as possible, language was kept as is to preserve the nuances of conversation and response. This interview reflects Susan Sherman's memories in conversation with Stephanie Anderson. All recollected events and contexts are true to the best of her estimation, and we believe her! — FER

Stephanie Anderson's scholarly work has recently appeared or is forthcoming in Momentous Inconclusions: The Life and Work of Larry Eigner, Post45, and Women's Studies, and her latest book of poetry is If You Love Error So Love Zero. She co-edited All This Thinking: The Correspondence of Bernadette Mayer and Clark Coolidge and edited Spies in the Audience, a book of interviews with women small press editors and publishers (forthcoming). She lives in Suzhou, China, where she is an assistant professor at Duke Kunshan University.

References

- Susan Sherman, "Creativity and Change: IKON, the Second Series," 2-4. Access via https://archives.worldlit.org/ikon-pdfs/IKON-OKLAHOMA-final-draft-2.pdf.[⤒]

- America's Child: A Woman's Journey Through the Radical Sixties (Willimantic, CT: Curbstone Books, 2007).[⤒]

- Sherman's essay on IKON's history and the complete IKON Series 2 archive are available at http://archives.worldlit.org/ikon-archives.html [⤒]

- Sherman's memoir is America's Child: A Woman's Journey Through the Radical Sixties (Curbstone Press, 2007).[⤒]