Little Magazines

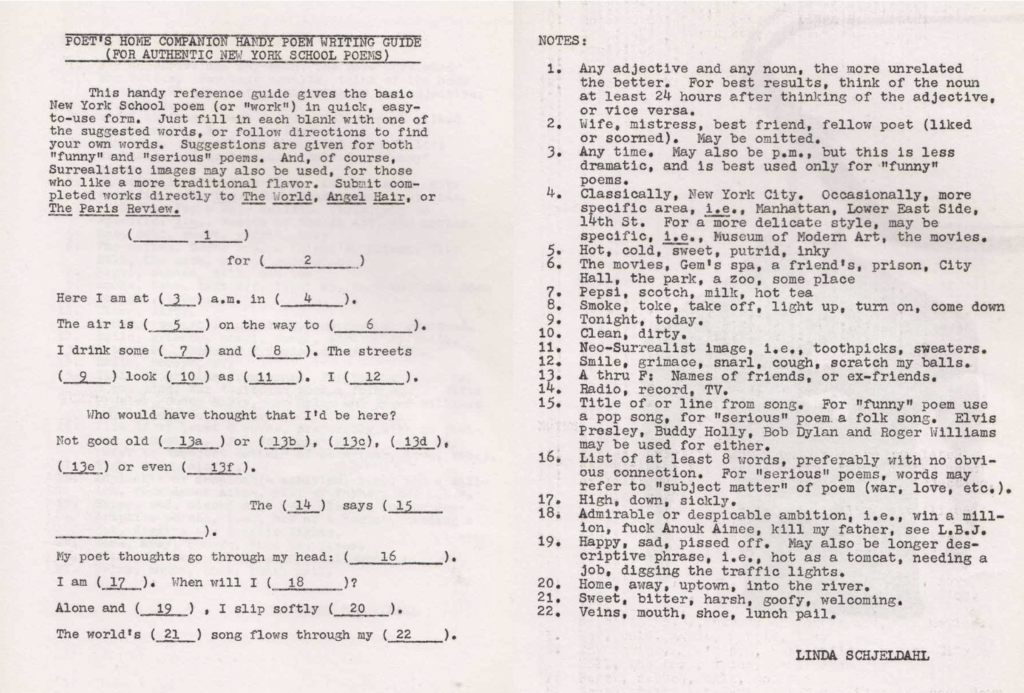

A couple of years ago, at the height of the first summer of the pandemic, when it felt like the world was coming apart at the seams (or, at least, that I was), you would have found me in a hot little tenement in Edinburgh, feverishly trying to finish my Ph.D. thesis. I was right at the end of this process, and searching for an opening gambit — a neat, pithy little anecdote that would somehow exemplify my whole argument: that the New York School and New York School scholarship had a problem with gender; that non-male writers had been ignored and marginalized; and that the canon of the School needed a new approach — a (re)vision, in Adrienne Rich's terms.1 And then somewhere (I truly wish I could remember where) I stumbled across a small chunk of something called "The Poet's Home Companion Handy Poem Writing Guide (For Authentic New York School Poems)."2

"This handy reference guide gives the basic New York School poem (or 'work') in quick, easy-to-use form," it begins. "Just fill in each blank with one of the suggested words, or follow directions to find your own words. Suggestions are given for both 'funny and 'serious' poems . . . Submit completed works directly to The World, Angel Hair, or The Paris Review."3 What follows is a write-by-numbers poem template, accompanied by instructions such as — for the title — "Any adjective and any noun, the more unrelated the better. For best results, think of the noun at least 24 hours after thinking of the adjective, or vice-versa."4 For a location in the first line, the suggestion is: "Classically, New York City. Occasionally, more specific area, i.e., Manhattan, Lower East Side, 14th St. For a more delicate, may be specific, i.e., Museum of Modern Art, the movies."5

The guide is an instantly recognizable pastiche of the self-proclaimed "I do this, I do that" poems that were written by Frank O'Hara in the 1950s and early 1960s, and which have since come to stand in — rightly or wrongly — for the New York School aesthetic as a whole.6 For example, O'Hara's poem "The Day Lady Died" begins:

It is 12:20 in New York a Friday

three days after Bastille Day, yes

it is 1959 and I go get a shoeshine7

The template for the guide begins:

Here I am at ( 3 ) a.m. in ( 4 ).

The air is ( 5 ) on the way to ( 6 ).8

A perhaps surprising predilection for punctuation aside, this appears to be arch yet seemingly affectionate mockery; a deeply knowing wink at a reader whom it imagines as similarly in on the joke. It goes on to draw attention to trope after trope of New York School writing: namedropping ("Who would have thought I'd be here? / Not good old ( 13a ) or ( 13b ), ( 13ac ), ( 13d ), / ( 13e ) or even ( 13f )"); engagement with pop culture ("15. Title of or line from song. For 'funny' poem use a pop song, for 'serious' poem a folk song. Elvis Presley, Buddy Holly, Bob Dylan and Roger Williams may be used for either"); enthusiasm for consumer capitalism (from "Gem's spa" to "Pepsi"); the inheritance of Surrealism ("11. Neo-Surrealist image, i.e., toothpicks, sweaters").9 Indeed, the guide seems to exhibit intimate knowledge not just of a poetic style, but a literary scene — the indication of where to submit the finished poems is finely calibrated, suggesting The World, the house organ of The Poetry Project at St Mark's Church In-the-Bowery, Angel Hair, helmed by Anne Waldman (along with Lewis Warsh), and The Paris Review, which in 1968, when the guide first appeared in print, was publishing Vito Hannibal Acconci, Jim Carroll, Clark Coolidge, Kenneth Koch, Bernadette Mayer, Aram Saroyan, Tony Towle, Waldman, and Warsh, and an interview with Jack Kerouac by Ted Berrigan (all, in fact, in one issue: Issue 43, Summer 1968). The guide is, in other words, a viciously joyful inside joke.

"The Poet's Home Companion Handy Poem Writing Guide (For Authentic New York School Poems)" was written by Linda Schjeldahl and published in a one-shot mimeograph magazine called Poet's Home Companion, edited by Carol Gallup. Both poet and editor are difficult to locate in the history of the New York School, although their surnames will undoubtedly seem familiar to those interested in the school's soi-disant "second generation."10 In 1968, Linda Schjeldahl was married to Peter Schjeldahl — then primarily a poet, now primarily known as a major, and very brilliant, art critic and essayist — and Carol Gallup was married to Dick Gallup, who is often listed alongside Berrigan, Ron Padgett, and Joe Brainard as one of the central (male) writers who inherited the mantle of O'Hara, Koch, John Ashbery, and James Schuyler (literary history adores a foursome).11

It is frustrating, as a quote-unquote feminist scholar, to be forced to introduce these women with recourse to their then-husbands (both couples would divorce). Yet it is also, unfortunately, practical. Working in the UK in the current moment, I am both geographically and generationally detached from the downtown scene into which Poet's Home Companion was published, and as such, I have found it incredibly difficult to find information on these two women, particularly Schjeldahl.

But here's what I know: I know that they were around the Lower East Side in the heyday of the second generation — the time between the death of O'Hara and the founding of The Poetry Project in 1966, and the scene's fragmentation westwards from the mid-1970s onwards. I know that there is an incredible photograph taken on Easter Sunday 1968 at the Staten Island Ballfield, of both women with some of the more famous members of that community: Warsh and Waldman and Berrigan and Padgett and George Schneeman and Katie Schneeman and a host of children clutching bats and balls. I know that Schjeldahl was born in 1942 as Linda O'Brien. I know that on the 28th of July, 1966, she attended Frank O'Hara's funeral at the Green River Cemetery in Springs, Long Island.12 I found in an April 1967 edition of the Rhode Island Herald ("the only English-Jewish Weekly in Rhode Island and Southeast Massachusetts") an article on an installation by the artist Les Levine, with a photo captioned: "LUNGLIKE WALLS — Les Levine, creator of disposable rooms, squeezes the lunglike wall in one of his three disposable rooms which went on view last week at the Architectural League. John Margolies looks on as Linda Schjeldahl tapes another inflatable wall."13 I know that Linda features in Lewis Warsh's "New York Diary 1967" as one of the many people whom he records endlessly arriving and leaving the apartment he shared with Anne Waldman at 33 St. Mark's Place. I know that for a while she lived with Peter, and that according to Waldman, "sometimes we all ended up at their apartment on 3rd Street" after readings at The Poetry Project, or just for hours spent "smoking dope and listening to music and talking about poetry and writing poems together."14 I know that on the 2nd of February 1972, Linda took a photograph of Lee Crabtree, the pianist of Ed Sanders' band The Fugs, kneeling on a carpet floor covered in little piles of — what? Checks? Compliments slips? The photograph appeared on the cover of Crabtree's An Unfinished Memoir, for which Peter Schjeldahl wrote the preface. I know that at the back of Ted Berrigan's Collected Poems, Linda is listed, with both surnames, as "Editor, writer; at one time married to Peter Schjeldahl,"15 and on the 9th of September 1974, she wrote to Herb Yellin on IntextPress letterheaded paper, signing herself "Linda Schjeldahl, Editor," and that for some reason, at the time of writing, this letter is available for purchase.

I also know that the only mention of Linda on Peter Schjeldahl's Wikipedia page reads: "Schjeldahl married and later divorced a woman whom he publicly referred to as 'L.'" In the citation there is a link to a memoir-esque essay in the New Yorker called "The Art of Dying," in which Schjeldahl writes:

L., who is no longer alive, became pregnant on our second date, in 1963. A backstreet abortion in Chicago left her sterile. I married her out of guilt mixed with infatuation. (She was wild and adored me while sleeping around, as I did, too, but I couldn't keep up.) We lasted for most of five years, possibly because a man I disliked had said that he gave us three months.16

This was how I found out that Linda Schjeldahl/O'Brien died. I don't know when.

***

When I first read "The Poet's Home Companion Handy Poem Writing Guide (For Authentic New York School Poems)," I thought it was interesting mainly because it was a case of two women — a poet and an editor — collaborating in creating something that displayed a profound intimacy with New York School writing and its attendant milieu. It felt like an inside job, but from people who — at least according to any narrative I had so far come across — were not being positioned as insiders.

Yet what became increasingly fascinating to me was the idea that this arch lampoon was being performed very specifically through the lens of gender, and its relationship to writing and to readership. The title of Gallup's mimeograph echoes both Woman's Home Companion (which was published in the United States from 1873 to 1957) and Ladies Home Journal (which has been in circulation since 1883), and Schjeldahl's instructions also seem to draw on the twee, gendered style of these magazines, using the language of recipes and household articles in order to give tips "for best results." In the context of the magazine as a whole, this becomes even more apparent. The contents page lists fourteen sections, including "LETTERS," "FOOD," "FASHION," "THE HOME," and "MEDICINE." This seemingly conventional list is peppered with piquant little surprises, however, such as "PORNOGRAPHY" sitting primly between "PERSONAL" and "SOCIETY," and it is this sense of mild subversion that characterizes the magazine throughout — a typically New York School air of camp insouciance. Indeed, it is a New York School mimeo through and through, from the list of contributors — which includes Bill Berkson, James Schuyler, Anne Waldman, Joe Brainard, Lewis Warsh, Ron Padgett, Barbara Guest, John Giorno, Kenward Elmslie, Jane Freilicher, George Schneeman, and Alex Katz — to the tersely unceremonious attitude of the editorial note: "The Poet's Home Companion is edited by Carol Gallup and will never appear again. There are 100 copies." This once again stands amusingly at odds with the veneer of domestic femininity in which the magazine is wrapped, and one wonders if the declaration that the magazine "will never appear again" is a teasing rib about the regularity with which magazines during the mimeograph revolution popped up and receded. Waldman writes of the impetus in setting up The World in 1967 that "there had been a lull in the little magazine blitz, [Diane] di Prima and LeRoi Jones's Floating Bear was subsiding, Ed Sanders's Fuck You/ a magazine of the arts and C magazine, edited by Ted Berrigan, weren't coming out regularly."17 Gallup's flippantly obdurate/obdurately flippant editorial stance is, in fact, reminiscent of both C and Fuck You: Berrigan once claimed that "I had an idea that the New York School consisted of whomever I thought,"18 and Sanders's motto for Fuck You was "I'll print anything."19

Yet the subversiveness of Poet's Home Companion could also be read as a kind of simmering anger — perhaps this magazine "will never appear again" because it is edited by Carol Gallup, and who is that, anyway? Considering the way in which Gallup could be reductively seen only as the one-time wife of Dick Gallup, it also seems notable that her mimeo features not only Ron Padgett, George Schneeman, Ted Berrigan, and Peter Schjeldahl, but also Pat Padgett, Katie Schneeman, Sandy Berrigan, and Linda Schjeldahl — all of whom were less well-known than their respective husbands. This feels like a deliberate counterbalance to the kind of scene laid out in the collaborative poem "80th Congress," written by Ted Berrigan and Dick Gallup and published in a 1967 issue of The World, in which "Anne & Lewis's" is "where it's at / On St. Mark's Place, hash and Angel Hairs on our minds," into which fold is welcomed "Peter Schjeldahl / Who is new and valid." While Berrigan and Gallup make this artistic assessment, "Anne makes lovely snow-sodas."20 Two years after Poet's Home Companion, Ron Padgett and David Shapiro would publish An Anthology of New York Poets, a collection of twenty-six male writers, plus Bernadette Mayer. In their introduction, Padgett and Shapiro write: "Who knows why we selected whom we did? Does knowing a poet help you understand his work any better? We happen to know almost all the poets in this book (there is one we have still to meet), and most of these poets know each other as well."21 All, I suppose, were "new and valid," while others were busy making "lovely snow-sodas."

It's not only Linda Schjeldahl's guide that tackles this apparently closed scene. Piece after piece in Carol Gallup's magazine seems to attend to women and gender. Some do so in high irony, as in James Schuyler's "Favorite Foods of Literary Lights," which consists of stanza-length recipes "by" famous literary women, in which most are credited as the wives of their (generally more famous) literary husbands, such as "Elizabeth Hardwick (Mrs Robert Lowell)" and "Caroline Gordon (Mrs Allen Tate)." The gambit is rendered most ludicrously in crediting the German writer and actress Erika Mann as "Mrs W.H. Auden"; Mann married Auden in 1935 in order to gain British citizenship after criticizing Nazi Germany — both were gay. The recipe attributed to her is "Dead Man's Leg," "which is a most particular favorite with my husband."22 Other pieces address women sweetly, genuinely, and directly, as in Bill Berkson's poem in honor of Anne (presumably Waldman) and her birthday: "Yes, Anne, it's life you like and you we like for liking it today."23 Waldman herself provides the "PERSONAL" section, which turns out to be an account of where she was for various full moons, followed by a chunk of her dream journal in which she dreams of "Hundreds and hundreds of women marching."

Still other works, like the opening letter to the editor from Katie Schneeman, come at things more obliquely. Schneeman writes:

Dear Carol,

Sorry not to have written anything for your magazine. Did have a good interview with Ted tho just tonight but it was full of too many blow-jobs to write about in much detail.

_________ is apparently the champion. Does that surprise or put you down?

_______ couldn't make it up the butt, but has since learned. ______ is Ted's sister and he is going to Iowa without having even come near to fucking me, tho I did run thru the room naked one night as he was sitting naked in a chair for George.

Good luck on your magazine.

Love,

Katie

P.S. _____ really loves to be fucked up the butt.24

This may seem anything but oblique, but its relationship to the gendered milieu of the second generation is nuanced and highly considered. Schneeman's emphasis on casual sexual explicitness recalls much of the work by men being published in little magazines of the time, and perhaps in particular the editorial tone adopted by Ed Sanders for Fuck You, in which, for example, he describes the poet Carol Bergé as "the poetess . . . The entire Editorial Board wd love to freak a dick in her."25 Sanders' editorial writing is a crafted piece, intended to be read alongside and as comparable to the work of the other writers and artists published in the issue, and so his objectification becomes part of the avant-garde vulgarity of the magazine as an artistic project, and can be shielded from scrutiny as such. It's art (baby). Much of this focus on sex was configured as part of the ideas of artistic fraternity being fostered within the downtown scene — a form of homosocial bonding to replace, perhaps, the subcultural bonds of shared queerness that arguably united John Ashbery, Frank O'Hara, and James Schuyler in the first generation. Angel Hair 3, for example, features Ted Berrigan's "Bean Spasms" (a precursor to Berrigan and Padgett's collaboration of the same name), which is dedicated to George Schneeman, and ends its first section with a reference to "the hair on yr nuts & my / big blood-filled cock."26 In her letter, Katie Schneeman writes to Gallup in much the same tone as Berrigan or Sanders do elsewhere — as a peer, a sister-in-arms, a titillating gossipmonger, an objectifier, a fellow fucker.

All of Gallup's contributors — whether writing dream journals, recipes, how-to guides, kitchen sink dramas, or scimitar-shaped odes to the opera singer Brenda Lewis (in the particularly delightful case of Kenward Elmslie) — are not only engaging in a parodic imitation of women's magazines, but also, through this, prodding at the marginalization and minority of women's reading material. Gallup's editorial vision is one in which this material becomes reframed; if not reclaimed, then at least poked a bit, questioned, variously elevated and ridiculed, turned upside-down. In a scene dominated by and oriented around men, Schjeldahl's piece in particular picks up the language of domestic instruction manual, adds an anticipatory dash of Bernadette Mayer's 1970s writing experiments, and — firmly, unequivocally, with smirk and arched eyebrow — lays claim to the mantle of the New York School.

***

Two contentions:

- "The Poet's Home Companion Handy Poem Writing Guide (For Authentic New York School Poems)" is a better benchmark for New York School poetry than the O'Hara poems (and in turn the Berrigan and Padgett poems) that it parodies, because it adds in the layer of arch self-awareness and play that O'Hara himself is engaging in when he terms his own work, "I do this, I do that" poems. It holds within it this sense that poetry — as an art form, and perhaps especially as a pursuit — is simultaneously very serious, and very funny.

- One of the most famous poems of the second generation of the New York School is not exactly or entirely written by who we think it was written by.

***

Ted Berrigan's "Red Shift" is cited by the Poetry Foundation as one of his "greatest works," and by various critics as a "remarkable self-elegy," "one of his last major works," "dazzling," and "iconic."27 It is an excellent poem, weaving the delicate intangibility of surrealist imagery with the hard surfaces of "I do this, I do that" materialism, in lines like "The air is biting, February, fierce arabesques on the way to tree in winter streetscape." Here one cannot accuse Berrigan of sounding like a dime-store O'Hara; he is instead his own kind of city poet, alternately wispy and stubborn, full of bullish love for "that painter who from very first meeting / I would never & never will leave alone until we both vanish into the thin air we signed up for & so demanded."28

Berrigan's posthumous Collected Poems was lovingly edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan in 2005, and Notley's notes at the back are meticulously curated. It is only here that it is pointed out that:

"Red Shift" essentially follows an outline for a fill-in-the-blanks "New York School poem," as printed in a one-shot mimeo magazine The Poets' Home Companion [sic], edited by Carol Gallup. The form itself was devised by Linda O'Brien (Schjeldahl). The magazine was published in the late 60s, but Ted rediscovered it in the 70s and within it the parodic procedure for writing a poem such as one of his own personal poems. By following the parody, he rejuvenated the original form and created a brilliant, passionate work.29

There is, then, a kind of circular flow chart (if you'll forgive the Ashbery pun) between O'Hara's "I do this, I do that" poems, the "personal" poems Berrigan was already writing, Schjeldahl's piece (which draws on both), and "Red Shift." A simplistic, patrilineal, Bloomian understanding of "Red Shift" seems to point directly back to O'Hara, but this fails to consider the way in which Schjeldahl is the mediator between them, the invisible link in the chain of the New York School canon. Or, indeed, the way in which she and Gallup might bypass such Sedgwickian homosociality altogether, engaging instead in their own negotiations with influence and tradition. Either way, "Red Shift" — "brilliant, passionate" — is not the work of a single male genius, but rather, in a very real sense, a collaboration with a woman who has been erased from the history of the New York School.

***

It is occasionally a strange (as well as a fortunate, frustrating, energizing, and silly) thing to be a researcher of the recent past. You are at once within touching distance of your subjects, and very far away — the fabric of their clothes rustles just so, their laughter rings out for mere seconds, then fades. They have left so much (the excess lead from pencil marks not yet blown off the sheet) and yet somehow so little (I still do not know the year that Linda Schjeldahl died).

Most often, I work on writers whom I — in search of the right angle, legitimacy, funding — term "overlooked" or "forgotten" or "erased." And yes, they're missing from the anthologies, from the hardbound classmarked syllabus texts, the fat scholarly works — or they're smuggled in via the footnotes, credited only by their first names; preceded by modifying relations such as "his wife, X," "his sister, Y." But sometimes this frame starts to sit uncomfortably with me. After all, these people I have termed invisible perch in technicolor on mantlepieces in family homes, they have nieces that can tell you what fragrance they wore, if you want to know, and their scarves are still wrapped around the necks of their friends. No one has forgotten them; they are remembered daily. (Indeed, such formulations become even more patently ridiculous when the writers are still alive.)

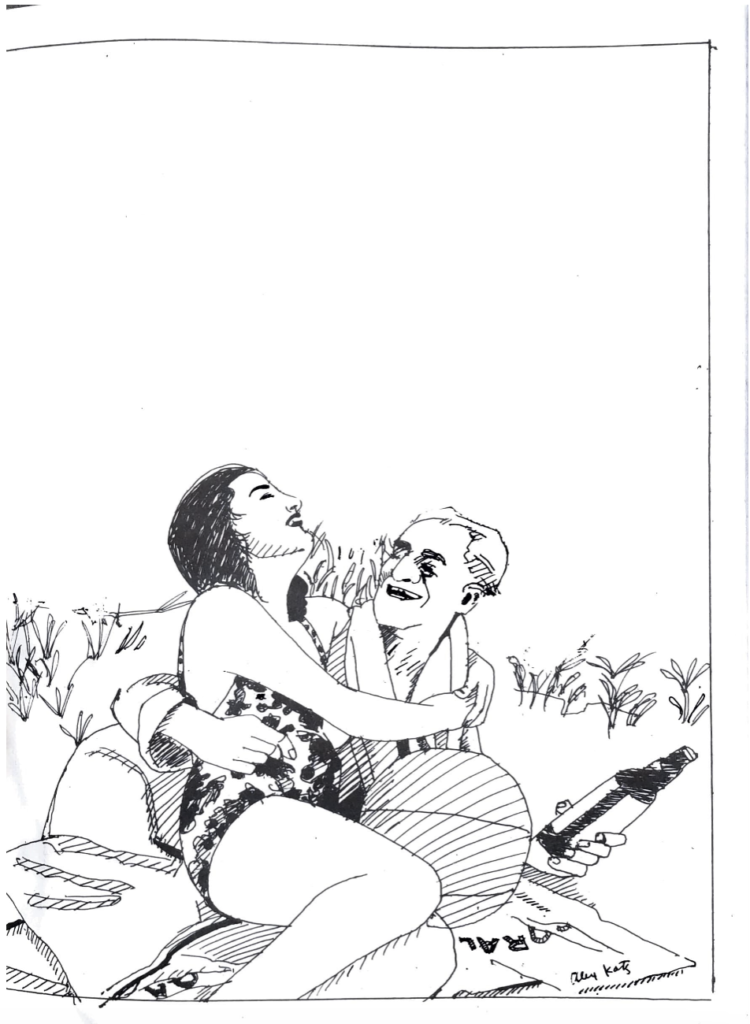

I presented a version of this essay at the Network for New York School Studies symposium in Paris, in April 2022, to a room that included people who had lived on the Lower East Side before I was born, who had attended iconic Poetry Project readings, who understood how mimeograph machines actually work. I ended the paper with a plea: if anyone knows anything about these women, let me know, I want to know. Over the next few hours people would mention in conversation that they'd enjoyed the paper, that the "Guide" was so much fun and oh yes, Carol, I can put you in touch or well you could speak to Ada about Linda, of course. I haven't, yet. Instead, in working on this essay, I found a piece of art criticism on Alex Katz, whose drawing of two people lying on a beach mat, laughing and drinking, appears in Poet's Home Companion. In it, Vincent Katz (poet, art critic, and also the artist's son) writes about Katz's 1968 artwork One Flight Up, a large-scale sculptural gathering of oil-on-aluminium portraits, arranged together on a long table, eyes at eye level. Envisioning an organic encounter with this scene, Vincent Katz writes:

Streetlights glow, reflected in puddles and on wet pavement. A chill runs through you, as you hurry up Fifth Avenue. You light another cigarette while waiting for the buzzer. Climb a flight of dingy stairs into a bright loft filled with the smoke of conversation and living.

He goes on to name the sitters for the portraits: Frank Lima, Sandy and Ted Berrigan, Jane Freilicher, Harry Mathews, Joe Brainard, John Ashbery, Lewis Warsh, Anne Waldman, describing what they're wearing ("Bill Berkson, poet, critic, and Top Ten Best Dressed List, is wearing a black turtle neck with cashermere [sic] jacket and pinky ring"), what they're discussing ("the latest Kenneth Koch play") and what they're smoking ("from the echoing angles of Al Held's and Irving Sandler's cigars to Christopher Scott's cigarette"). It is, he writes, "[a] typical gathering such as one might find at any of a number of locations on any of many evenings in this city of New York in this year of 1968." Notable, then, that in amongst these luminaries and famous names, Alex Katz includes — at what Vincent Katz describes as "the cocktail party of his imagination" — "Linda Schjeldahl with purple tassle [sic] earrings matching her dress."30 No mention of Peter.

I pull up image after image of One Flight Up, from shows at the Timothy Taylor Gallery in 2007, the National Portrait Gallery in 2010, at the Dallas Museum of Art in 2019, thirty portraits at different angles, photo after photo. I hold my laptop up to my eyes, scanning for purple earrings. I still can't find her.

Rosa Campbell is Associate Lecturer in Modern and Contemporary Literature at the University of St Andrews (UK), where her primary research and teaching interests include poetry and poetics, feminist/queer studies, intersections with visual art, and the New York School. She is the author of Pothos (Broken Sleep Books, 2021), a lyric essay on grief and houseplants, and the editor of a forthcoming Selected Poems of V.R. "Bunny" Lang (Carcanet, 2024).

References

- For Rich, "re-vision" is "the act of looking back, of seeing with fresh eyes, of entering an old text from a new critical direction" (Rich, "When We Dead Awaken:Writing as Re-Vision," College English 34, no. 1: 18). This is a term that I am also re-visioning, in the sense that my "(re)vision" of the New York School is one that, as well as distancing itself from Rich herself (whose work remains significant and influential, yet whose transphobia — exhibited most clearly in her support for, and citation in, Janice Raymond's viciously anti-trans The Transsexual Empire (1979) — lies fundamentally at odds with the values of my research and my life), not only aims to enter old texts from new critical directions, but also see with fresh eyes the arcane, airy, slippery structures of criticism itself.[⤒]

- It can be found in its entirety in the beautiful, fat, prohibitively expensive Neon in Daylight: New York School Painters & Poets (Rizzoli, 2014). Thanks are due to my friend Sam Buchan-Watts, who I believe got his cousin to take a photograph of the relevant pages to send to me. Later, Nick Sturm would unearth from his incredibly impressive personal digital archive a PDF scan of Poet's Home Companion, the magazine in which the guide appears, and generously email it to me.[⤒]

- Linda Schjeldahl, "The Poet's Home Companion Handy Poem Writing Guide (For Authentic New York School Poems)," Poet's Home Companion, ed. Carol Gallup (self-published, 1968), no page.[⤒]

- Schjeldahl, "Handy Poem Writing Guide," no page.[⤒]

- Schjeldahl, "Handy Poem Writing Guide," no page.[⤒]

- Frank O'Hara, "Getting Up Ahead of Someone (Sun)," The Collected Poems of Frank O'Hara, edited by Donald Allen (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 341[⤒]

- Frank O'Hara, "The Day Lady Died," The Collected Poems of Frank O'Hara, 325.[⤒]

- Schjeldahl, "Handy Poem Writing Guide," no page.[⤒]

- Schjeldahl, "Handy Poem Writing Guide," no page.[⤒]

- I have borrowed this sort-of joke from John Ashbery, who dubbed Ted Berrigan, Ron Padgett, Joe Brainard and Dick Gallup the "soi-disant Tulsa School" after the Oklahoma town in which they met.[⤒]

- Work by Peter Schjeldahl and Dick Gallup appeared in the Winter-Spring 1968 issue of The Paris Review, by the way.[⤒]

- Brad Gooch, City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O'Hara (New York: Harper Perennial, 2014), 472.[⤒]

- "Disposable Rooms Shown at Architectual League," The Rhode Island Herald (April 28, 1967), 11[⤒]

- Anne Waldman, "Introduction," angel hair sleeps with a boy in my head: the Angel Hair anthology, edited by Anne Waldman and Lewis Warsh (New York: Granary Books, 2001), xxiii.[⤒]

- "Notes," Ted Berrigan's Collected Poems, edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 727. [⤒]

- Peter Schjeldahl, "77 Sunset Me," [Online: "The Art of Dying"] The New Yorker (December 23, 2019), 41-42. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/12/23/the-art-of-dying.[⤒]

- Anne Waldman, "The World," From a Secret Location. https://fromasecretlocation.com/world/\[⤒]

- Harry Thorne, "'The New York School is a Joke': The Disruptive Poetics of C: A Journal of Poetry." Don't Ever Get Famous: Essays on New York Writing after the New York School, edited by Daniel Kane (Dalkey Archive Press, 2006), 74.[⤒]

- Ed Sanders, Fuck you/ a magazine of the arts, no. 2 (May 1962), no page.[⤒]

- Dick Gallup and Ted Berrigan, "80th Congress," The World Anthology, edited by Anne Waldman (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1969), 81.[⤒]

- Ron Padgett and David Shapiro, "Preface," An Anthology of New York Poets (New York: Random House, 1970), xxix.[⤒]

- James Schuyler, "Favorite Foods of Literary Lights," Poet's Home Companion, ed. Carol Gallup ([publisher not identified], 1968), no page.[⤒]

- Bill Berkson, "Anne's Birthday Out," Poet's Home Companion, ed. Carol Gallup ([publisher not identified], 1968), no page.[⤒]

- Katie Schneeman, "A Letter," Poet's Home Companion, ed. Carol Gallup ([publisher not identified], 1968), no page.[⤒]

- Ed Sanders, Fuck you/ a magazine of the arts 5, vol. 3 (May 1963), no page.[⤒]

- Ted Berrigan, "Bean Spasms," angel hair sleeps with a boy in my head: the Angel Hair anthology, edited by Anne Waldman and Lewis Warsh (New York: Granary Books, 2001), 38.[⤒]

- Andrew Epstein, "Lynn Emanuel Takes a Break with Ted Berrigan," Locus Solus (December 2013) https://newyorkschoolpoets.wordpress.com/2013/12/06/lynn-emanuel-takes-a-lunch-break-with-ted-berrigan/; Daniel Kane, "'Angel Hair' Magazine, the Second-Generation New York School, and the Poetics of Sociability," Contemporary Literature 45, no. 2 (2004): 331n1; Daniel Kane, "A Necessary Delight" (Review), PN Review 32, no.5 (2006): 83; Nick Sturm, "Lost in the Stacks: The Raymond Danowski Poetry Library on the Radio," Crystal Set (March 2019) https://www.nicksturm.com/crystalset/2019/5/29/lost-in-the-stacks-teaching-the-archives.[⤒]

- Ted Berrigan, "Red Shift," The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan, edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 515.[⤒]

- Alice Notley, "Note on 'Red Shift,'" The Collected Poems of Ted Berrigan, edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, and Edmund Berrigan, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 701-702.[⤒]

- Vincent Katz, "Permanent Evanescence: The Art of Alex Katz," Revista de História da Arte e Arquelogia, no. 3 (2000): 129-141.[⤒]