Little Magazines

I.

So far in my learning through the Little Magazine in America Collection at University of Denver (DU) Libraries, my process has been this: mapless, I make my way through what's in front of me, whatever materials I've pulled from the collection on a given day. I look and listen for cues. I read a web. The web I've been reading the past couple months is one that begins with Duende, a mimeographed, side-stapled magazine published by Larry Goodell in Placitas, New Mexico from 1964-66.

In A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960-1980, Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips describe Duende as "one of the most down-to-earth, and yet still lunar, of the mimeographed magazines of the 1960s".1 Each of the magazine's 14 issues features the work of one poet, and the work appears in this order:

History of the Turtle, Book 1 (1964), Ronald Bayes

Virgules and Déjà Vu (1964), A. Fredric Franklyn

Cockcrossing (1964), Richard Watson

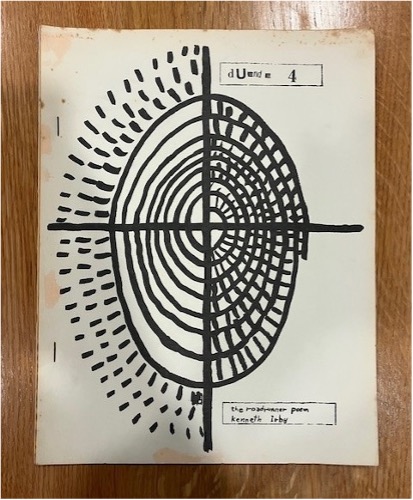

The Roadrunner Poem (1964), Kenneth Irby

Some Small Sounds From the Bass Fiddle (1964), Margaret Randall

Murder Talk; The Reception: (Suggestions for a Play); Five Poems; Bed Never Self Made (1964), Larry Eigner

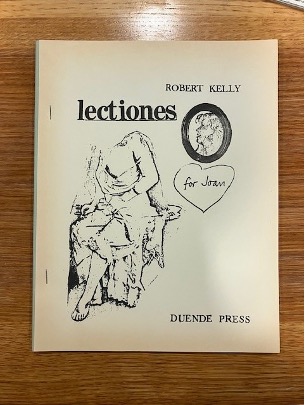

Lectiones (1965)

Movements / Sequences (1965), Kenneth Irby

Se Marier (1965), William Dodd

History of the Turtle, Book 4 (1966), Ronald Bayes

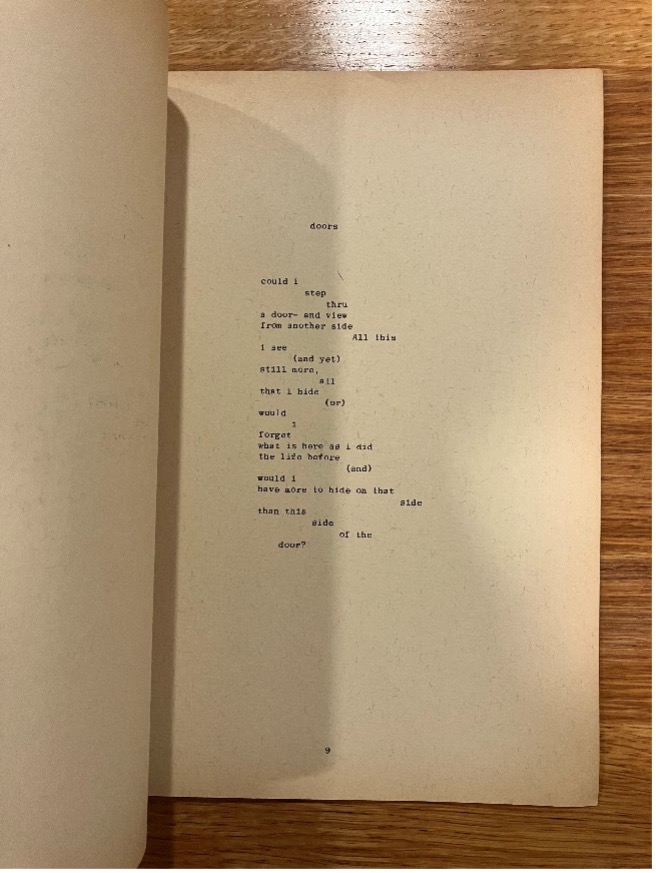

Poems (1966), Frederick Ward

Poems 1965 (1966), William Harris

Touch (1966), David Franks

Cycles (1966), Larry Goodell

Named after Federico García Lorca's concept of duende (see "Juego y teoría del duende" (Play and Theory of the Duende)), the magazine works against the clumsy artifice of "literary fashionmongers" of whom Lorca says, "we have only to pay a little attention and not surrender to indifference in order to discover the fraud." He goes on to say that the duende's arrival "means a radical change in forms. It brings to old planes unknown feelings of freshness, with the quality of something newly created, like a miracle, and it produces an almost religious enthusiasm."2

In 1962, Goodell took an English 121 class with Robert Creeley at the University of New Mexico (UNM). Creeley encouraged him to attend the Vancouver Poetry Conference of 1963, where Goodell met Bayes, Franklyn, and Watson. Spurred on by the conference, Goodell bought a Rex-Rotary mimeo machine and published the first issue of Duende in 1964.3

At the time, Fred Wah was publishing Sum: A Newsletter of Current Workings, first in Buffalo, New York, then in Albuquerque. Ward Abbott and Bryant Cashion were publishing The Desert Review out of Albuquerque. Previously, Judson Crews had published Suck-egg Mule, a Recalcitrant Beast out of the Ranches of Taos. The early to mid-'70s would see Carol Bergé's Center; Charlie Vermont and Charlie Walsh's Two Charlies Magazine; Alan Schiller's Stooge; and Goodell, Stephen Rodefer, Bill Pearlman, and Charlie Vermont's Fervent Valley published out of Alameda, Albuquerque, and Placitas, respectively.

Clearly, something was happening in New Mexico. I mean, Robert Downey made Greaser's Palace, one of the greatest acid westerns on film, in less than two weeks in the early '70s in Tesuque Pueblo and Santa Fe.

In The 60s Communes: Hippies and Beyond, Timothy Miller writes, "New Mexico became a great magnet for communitarians toward the end of the 1960s, a symbol of the entire rural countercultural impulse. Just why it happened there remains something of a mystery" (Miller 63). Some 240 miles north of Placitas, a morning's drive away, Drop City, one of the first rural communes of the decade, formed near Trinidad, Colorado in 1965. Drop City's founders, Gene Bernofsky, JoAnn Bernofsky, Richard Kallweit, and Clark Richert, rejected paid employment and social conventions, and worked toward a "love of integrated arts, creating multimedia extravaganzas, using color profusely, employing trash as source material, blending art with everything else in life".4

Talking with Colorado Public Radio in 2019, Richert said, "We weren't trying to be hippies and we didn't consider ourselves hippies. But the media world basically called us hippies."5 Informed by John Cage, Robert Rauschenberg, and Buckminster Fuller's work and performances that had taken place at Black Mountain College years earlier, the group moved toward building geodesic domes as structures for living.

A year into Drop City, Steve Baer, who was teaching in the architecture department at UNM and studying the geometry of the polyhedron, saw an opportunity for collaboration with the group in Colorado. They welcomed him, and Baer designed and refined structures there, introducing the zome, a dome-like structure that required fewer parts and could be easily altered. In 1967, Baer left Drop City for Placitas, where he founded Manera Nueva, sometimes called Drop South given its association with, and proximity to, the northerly original.6

II.

Looking through the run of Duende that's held by DU Libraries, I see a cursive note that draws my attention to the upper right-hand corner of an issue's front matter:

Kenneth Irby

January 1964

Albuquerque, N.M.

This inscription, usually in blue ink, can be found in eight issues of Duende that are part of the Little Magazine in America Collection, and in following the inscription the reader pieces together Irby's movement from Albuquerque to San Francisco to Berkeley, from January 1964 to April 1966. Per "Kenneth Lee Irby: A Chronology" by Kyle Waugh, Irby moved to Albuquerque in August 1963 and began writing book reviews for New York City-based Kulchur, working at the Sandia Corporation, continuing to write poems.7 Goodell published The Roadrunner Poem (Duende 4)in 1964, and later that year Irby moved to San Francisco. Shortly after that a move to Berkeley, and in that time his Kansas-New Mexico was published by Dialogue Press in Lawrence, Kansas, while Goodell published Movements/Sequences (Duende 8). Irby worked as a store manager at Duncan Macandrew, merchant tailor, which, as best I can figure, was located at 623 Clay Street in San Francisco, a few blocks from City Lights.

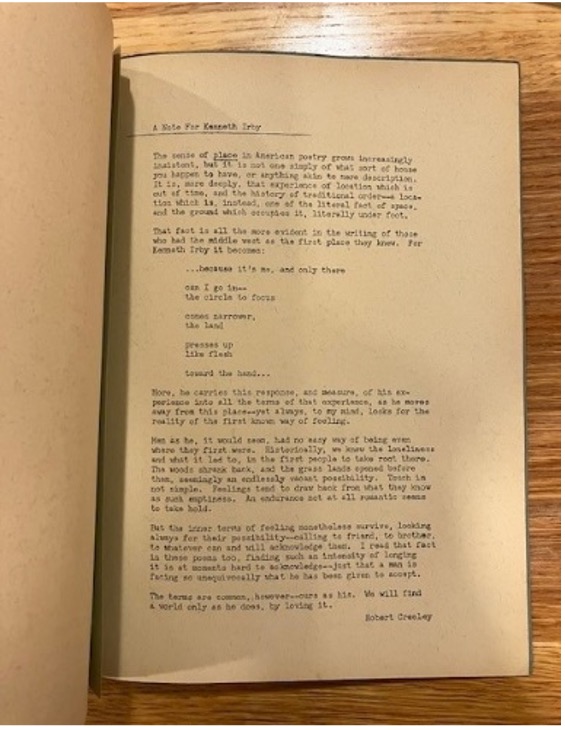

In "A Note for Kenneth Irby," an afterword in Movements / Sequences (Duende 8), Creeley writes, "The sense of place in American poetry grows increasingly insistent, but it is not one simply of what sort of house you happen to have, or anything akin to mere description. It is, more deeply, that experience of location which is out of time, and the history of traditional order — a location which is, instead, one of the literal fact of space, and the ground which occupies it, literally under foot."

Years later, in the essay "My New Mexico," Creeley echoes his sense-of-place thesis: "Whatever the newcomer's disposition toward it all, the place is adamantly a condition in all that she or he can do."8 I think here of Walter Pater's pronouncement that all art constantly aspires toward the condition of music, which is relevant to this discussion, and have you ever — have you even — listened to Bettye LaVette's 1968 version of "What Condition My Condition Is In"?

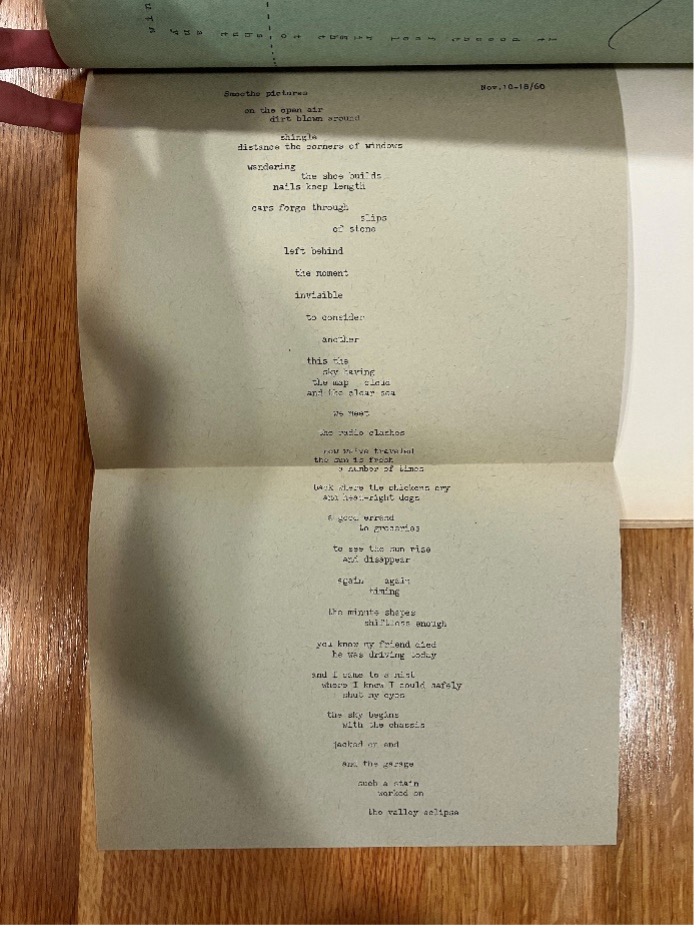

There are compelling patterns that emerge in Irby's writing as it's presented in Duende. Frequently, Irby specifies the stretch of days, or the very day, in which he's writing. In the preface to Movements / Sequences, Irby locates himself through this passage: "as now the cars' sounds out these windows and the clouds' unknown movements across the sun and bay, determine along with whatever thought ahead of time, the music being listened to, this being written; what moment I am in: this 5:23 pm of Monday, the 15th of February, 1965, 1436 Spruce St., Berkeley, California."

Toward the end of The Roadrunner Poem (Duende 4) in a biographical sketch, Irby writes, "It is impossible to write of what one has written or lived, except as the day is, out the window, now, explicit." The sketch is dated Saturday, April 11, 1964.

The day before, The Beatles had released their second album, The Beatles' Second Album. (What a title.) Five days later, The Rolling Stones would release their first album. Buffy-Sainte Marie had just released her first album, It's My Way! The Governor of Indiana had recently declared the Kingsmen's "Louie Louie" pornographic, saying that it made his ears tingle. The Supremes would soon have the first of five successive number-one songs with "Where Did Our Love Go." And The Staple Singers would become the first Black artists to perform at the Newport Folk Festival.

It was a leap year in which Ted Berrigan's The Sonnets, John Berryman's 77 Dream Songs, Robert Duncan's Roots and Branches, Ronald Johnson's A Line of Poetry, a Row of Trees, LeRoi Jones's (who a year later would be Amiri Baraka) The Dead Lecturer: Poems, The Dutchman and The Slave, Denise Levertov's O Taste and See, Frank O'Hara's Lunch Poems, and Theodore Roethke's The Far Field would be published.

Agnes Martin would paint The Tree. In a few years, she would leave New York and drive around the western U.S. and Canada before landing in Cuba, New Mexico in 1968.

Betye Saar would etch Mystic Chart for an Unemployed Sorceress.

After 14 years, James Hampton would complete The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations' Millennium General Assembly.

Freedom Summer would begin in June.

Three civil rights workers would be abducted and murdered by the Ku Klux Klan in Philadelphia, MS. In 1980 at the Neshoba County Fair only a few miles away, Ronald Reagan would launch his presidential campaign with his coded, racist "State's Rights" speech.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 would be signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson.

Congress would pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

Fannie Lou Hamer would co-found the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, challenge the all-white Mississippi delegation at the 1964 Democratic National Convention, and in doing so deliver televised testimony so powerful that the president attempted to preempt it with an impromptu press conference.

At the end of 1964, in a poem dated "6-14 Dec 1964" and titled "Sequence," a poem written for Goodell in Movements / Sequences, Irby writes,

How did I get here? how the hell did I end up here?9

There are those years whose turn to the next induces a vertigo, and the poems that Irby dates December 1964, apt there in their own space-time, call up a spinning.

In a Jacket2 feature on Irby's work, Benjamin Friedlander writes, "The world, of course, has a temporal aspect as well a spatial one, and perception necessarily shares in both, meeting the world where the two coincide. Again and again, perception brings us to a crossroad, a complex interplay of history and geography, memory and presence, given narrative and thematic expression in Irby's earlier poems."10

I love this crossroad in Movements / Sequences, a variation from "Three Variations (to follow the series for Roy Gridley)," dated "9 Dec 1964":

Christmas, then, in the heart's

plains, in the plains

blizzards blow toward home,

grain elevators stick up

lights on, blinking,

have made cathedrals

in the sight, bells rung

wreathes hung on

are silent,

but there, if you look up

4 am driving all night

home at Christmas time, the mind

will decorate, ever

green, and the sounds

toward the dawn, changes rung

on and on11

III.

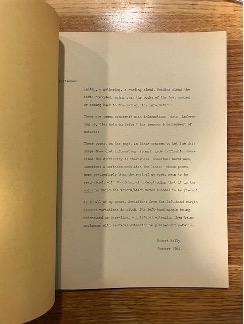

At the beginning of Robert Kelly's Lectiones (Duende 7) is a January 1965 foreword of sorts in which one reads, "These are poems concerned with information: data, informing us, 'le mots du tribu,' the sources & deployment of material." A year after Lectiones was published, Kelly gave a reading at Sir George Williams University in Montreal, Quebec and noted that he didn't think the poems held on paper, saying, "To some extent all of the poems that I've written, all of the poems anyone writes are scores for an eventual ideal performance in someone's mind's ear."12

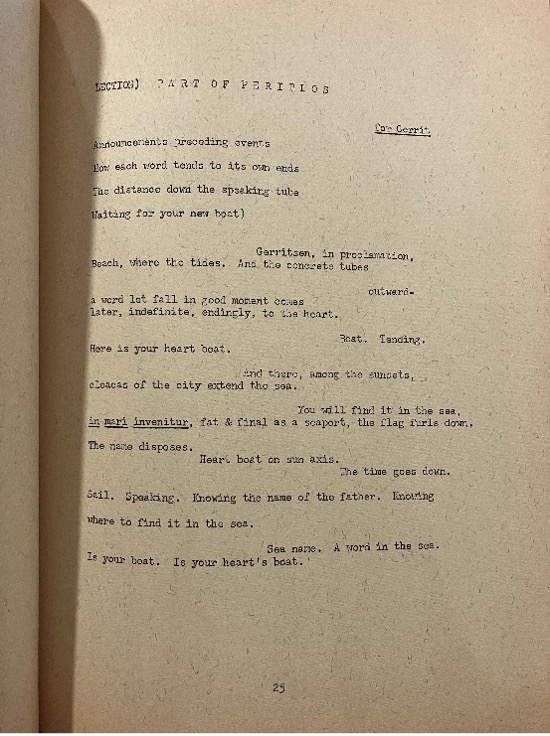

I'll point to "Lection) PART OF PERIPLOS" (pictured below) for the poet Gerrit Lansing, as proof that perhaps some of Lectiones's poems do hold up on paper.

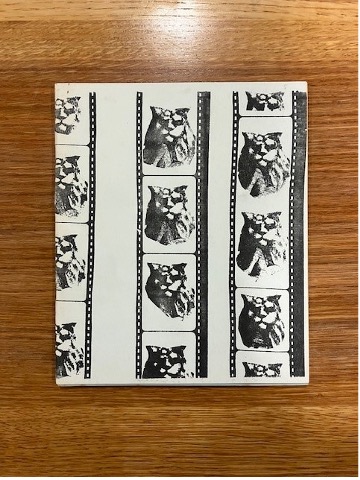

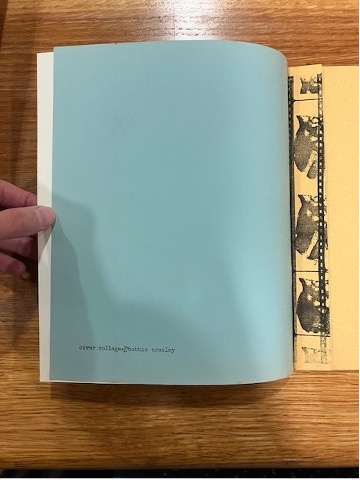

For me, one of the best parts of looking through Duende has been spending time with Bobbie Louise Hawkins's collages as they appear in and on Lectiones and Margaret Randall's Some Small Sounds from the Bass Fiddle (Duende 5). A Hawkins collage also appears on Goodell's Ode, the first broadside that Duende Press issued in 1964, and features the same lion's head that appears on Duende 5. When the aforementioned collages were published, Bobbie Louise Hawkins was Bobbie Creeley.

collages by Bobbie Creeley

Shortly after DU Libraries acquired the Little Magazine in America Collection, we acquired Bobbie Louise Hawkins's papers. For three decades, Hawkins led writing workshops and taught literary studies at Naropa University in Boulder, CO, about 30 miles from where I sit in Denver writing this conversation with myself and possibly you. A trove of photos is part of Hawkins's papers, and in that trove are pictures that were taken during the time in which Duende was published, others stretching on to Bolinas, CA in the '70s, others further on.

One of those pictures, one of the most beautiful, is a picture of Hawkins holding a cat in her Bolinas, CA garden. The picture, taken by Gerard Melanga in 1972, happens to be the cover photo of the 50th Anniversary Edition of On the Mesa: An Anthology of Bolinas Writing, edited by Ben Estes and Joel Weishaus, published by The Song Cave in 2021. Hawkins's poetry, which was not included in the original anthology, is now present in the form of three poems toward the beginning of the book.

In "All Morning the Rain," Hawkins writes,

Old photographs curl in the damp

We stay

caught, left over

with the litter that's left

to care for

Caught in life

Birth a debt

we keep paying

remembering13

Hawkins and Robert Creeley moved to Bolinas from Placitas in the early '70s. In the preface to On the Mesa, Estes talks of being drawn to "the counterculture literary puzzle that this very specific place in time stands for, a refuge for San Francisco Renaissance and Beat poets and prominent poets of the New York School and Black Mountain College all living and working together, in one place, for a brief period of time."14

Without New Mexico in the '60s, that puzzle is incomplete. As with Bolinas, ties to the Vancouver Poetry Conference, San Francisco Renaissance, Beat Generation, New York School, and Black Mountain College are present in Placitas in particular, and in Goodell's publishing work on Duende and later little magazine Fervent Valley. Placitas was a rural vortex that drew "'creative Outsiders who were part of the uprising against the nation's racism, exploitative socio-economic system, and the Vietnam War."15 Goodell is said to have called it Black Mountain West.

To contradict Timothy Miller, quoted earlier in this essay, the rural countercultural impulse as it pertains to New Mexico in the '60s is not much of a mystery. People were going through it, whatever "it" meant for any one person and the collective at the time, however they were feeling their way through, maybe bound for something and somewhere else, making what they saw fit to make.

In a 2015 interview with Iris Cushing, whose work on Umbra magazine appears in this Post45 cluster, Hawkins spoke to the temporal nature of all this shifting:

IC: What do you think of as the limits of the Beat Generation, time-wise?

BLH: Oh, I don't.

IC: You don't think of it having limits?

BLH: It's just something I never . . . I'd have to invent it, to think it. But really, what started to close down the poetry that was so heavy at that time, was music. When the Beatles came in, so when would that have been? Around the mid-1960s, I think the Beats went up to then. And they kept on for a while, because there was a lot of interrelationship between the musicians and the writers at that time. But when the flower children came in, the Beats were gone.16

IV.

There's more to be written about Duende.

Given space enough and time, I would go on about Larry Eigner's Murder Talk; The Reception: (Suggestions for a Play); Five Poems; Bed Never Self Made (Duende 6), which begins with an excerpt from a 1957 letter from Robert Duncan and unfolds gorgeously from there.

I would go on about Fred Ward's brilliant Poems (Duende 11), their glint, this recording of Ward reading his poems that Goodell made in Placitas in 1966.

I would say more about tracing A. Fredric Franklyn, author of Virgules and Déjà Vu (Duende 2), also known as Frederic Franklyn, Fredric Franklyn, Frederick Franklyn, and Fred Franklyn, to his role as "Man from Cincinnati in Piano Bar" in Mel Brooks's High Anxiety.

I would encourage you to listen to Goodell's 1964 recording of Ron Bayes reading History of the Turtle.

I would suggest that spending time with whatever draws your attention on Goodell's extensive Bandcamp page is a good way to continue parsing Duende and Goodell's poet-as-publisher ethos.

In a February 1964 letter sent from Mexico City, Margaret Randall, who was then editing and publishing El Corno Emplumado with Sergio Mondragón, wrote to Goodell: "At the recent Encounter of American poets here . . . I spoke about poetry in the US and mentioned DUENDE, WILD DOG, TISH, FLOATING BEAR, SUM, etc. as a new phenomena and the real 'heart' of what is going on in current verse publication."17 Later that year, Goodell published Randall's Some Small Sounds From the Bass Fiddle (Duende 5), and in her biographical note Randall writes of moving from Scarsdale, New York "to Albuquerque, New Mexico at age of 11, began to absorb desert, mountains, sense of space."

Both Randall and Goodell remain in New Mexico, Randall in Albuquerque and Goodell in Placitas. Elsewhere, looking for the real heart of what's going on, a reader learns a new topography through Duende.

Author's Note: Of the little magazines mentioned in this essay, Center, Stooge, and TISH are available to explore online at Reveal Digital's Independent Voices archive.

Shannon Tharp writes poems and essays, makes collages, listens to a lotta Wet Leg, and works as a librarian in Denver, Colorado.

References

- Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960-1980 (New York: Granary Books, 1998), 151.[⤒]

- Federico García Lorca, In Search of Duende, translated by Christopher Maurer and Norman DiGiovanni(New York: New Directions, 2010), 52-53.[⤒]

- Granary Books, The Larry Goodell / Duende Archive, 2. Access via: https://www.granarybooks.com/images/upload/goodellduende-prospectus.pdf.[⤒]

- Timothy Miller, The 60s Communes: Hippies and Beyond (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1999), 32.[⤒]

- Stephanie Wolf, "Clark Richert Helped Create Drop City. But That's Just Where His 50-Year Career Started," CPR News, June 5, 2019. Access via: https://www.cpr.org/show-segment/clark-richert-helped-create-drop-city-but-thats-just-where-his-50-year-career-started/.[⤒]

- Emily Silva, "Manera Nueva," Albuquerque Modernism, University of New Mexico. Access via: http://albuquerquemodernism.unm.edu/wp/manera-nueva-placitas/.[⤒]

- Kyle Waugh, "Kenneth Lee Irby: A Chronology," Jacket2, November 18, 2014. Access via: https://jacket2.org/article/kenneth-lee-irby-chronology.[⤒]

- Robert Creeley, The Collected Essays of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 439.

[⤒]

- Kenneth Irby, The Intent On: Collected Poems, 1962-2006, edited by Kyle Waugh and Cyrus Console-Șoican (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2009), 70.[⤒]

- Benjamin Friedlander, "The Walk to the Paradise Garden," Jacket2, November 18, 2014. Access via: https://jacket2.org/article/walk-paradise-garden.[⤒]

- Irby, The Intent On, 69.[⤒]

- Robert Kelly, "Robert Kelly at SGWU, 1966," SpokenWeb Montreal. Access via: https://montreal.spokenweb.ca/sgw-poetry-readings/robert-kelly-at-sgwu-1966/.[⤒]

- Ben Estes and Joel Weishaus, eds., On the Mesa: An Anthology of Bolinas Writing (Brooklyn: The Song Cave, 2021), 23.[⤒]

- Estes and Weishaus, On the Mesa, xi.[⤒]

- Gary L. Brower, "Introduction to Poems by Larry Goodell in the Malpais Review by Gary L. Brower," 3 dimensional poetry (blog), January 15, 2021. Access via: https://larrygoodell.blogspot.com/2021/01/untitled-p.html?m=0.[⤒]

- Bobbie Louise Hawkins, interview by Iris Cushing, Boulder, CO, October 31, 2015, transcript. Access via: https://www.centerforthehumanities.org/news/remembering-bobbie-louise-hawkins.[⤒]

- Granary Books, The Larry Goodell / Duende Archive, 7.[⤒]