Little Magazines

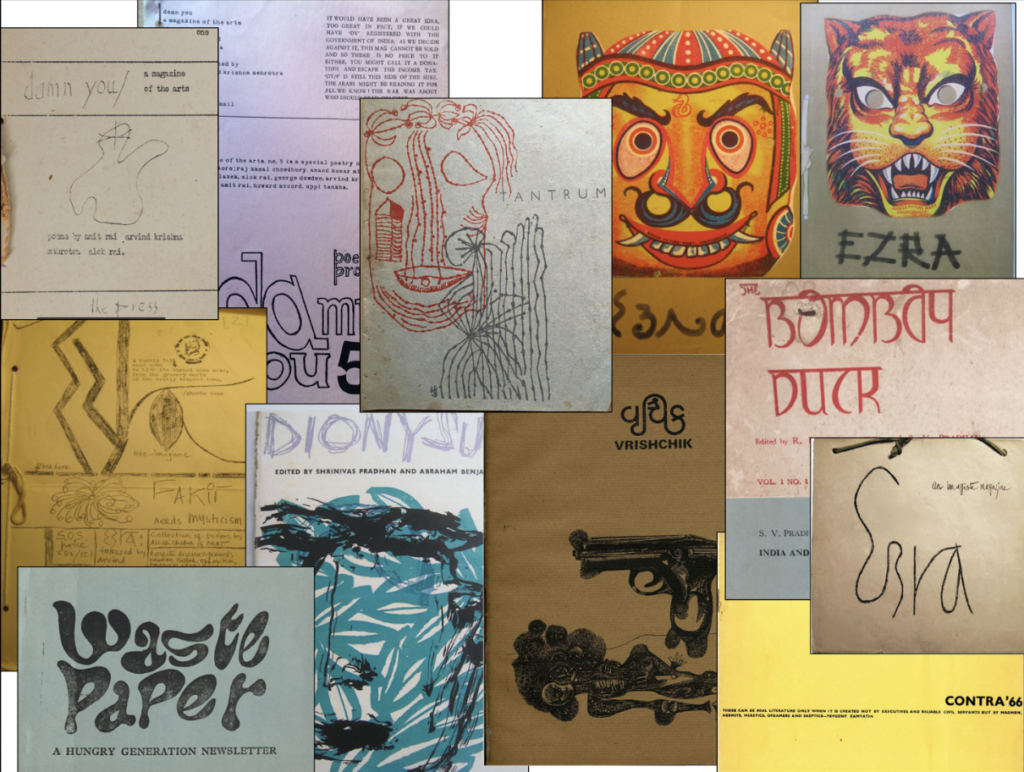

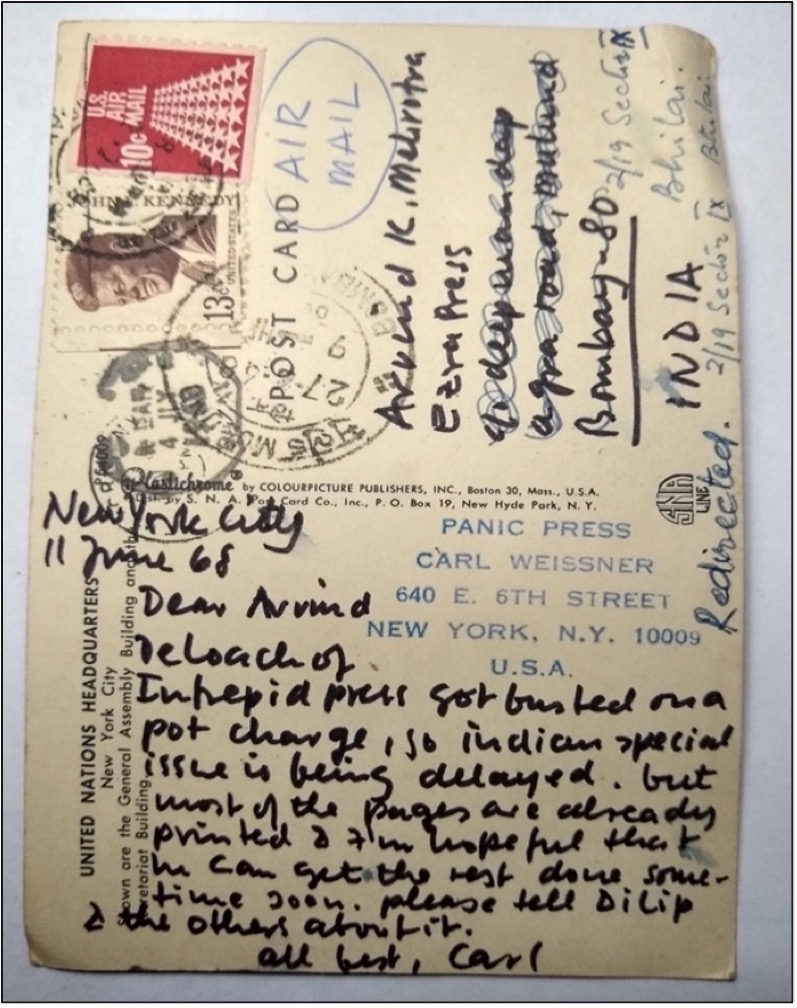

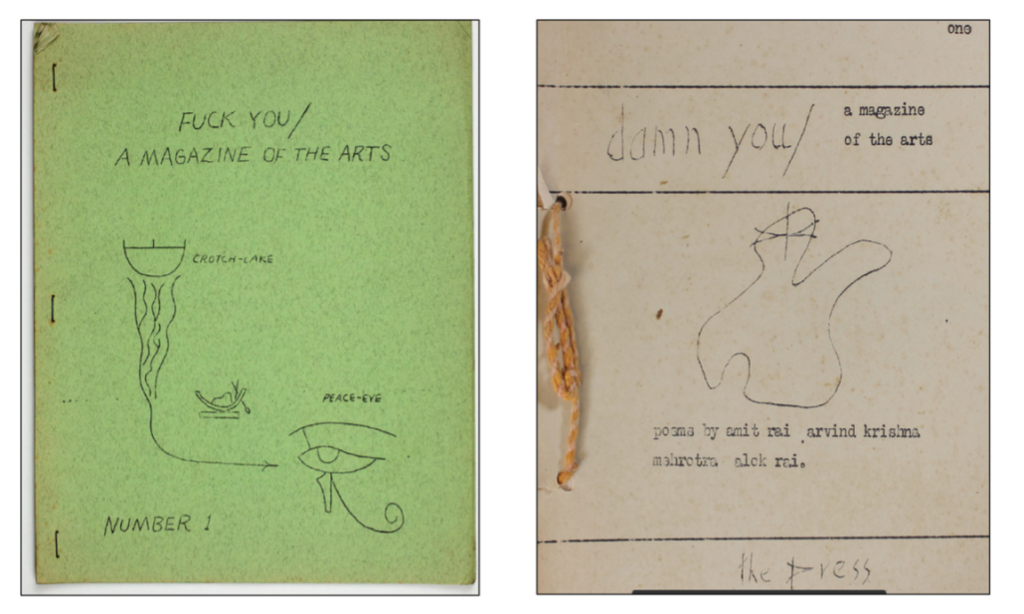

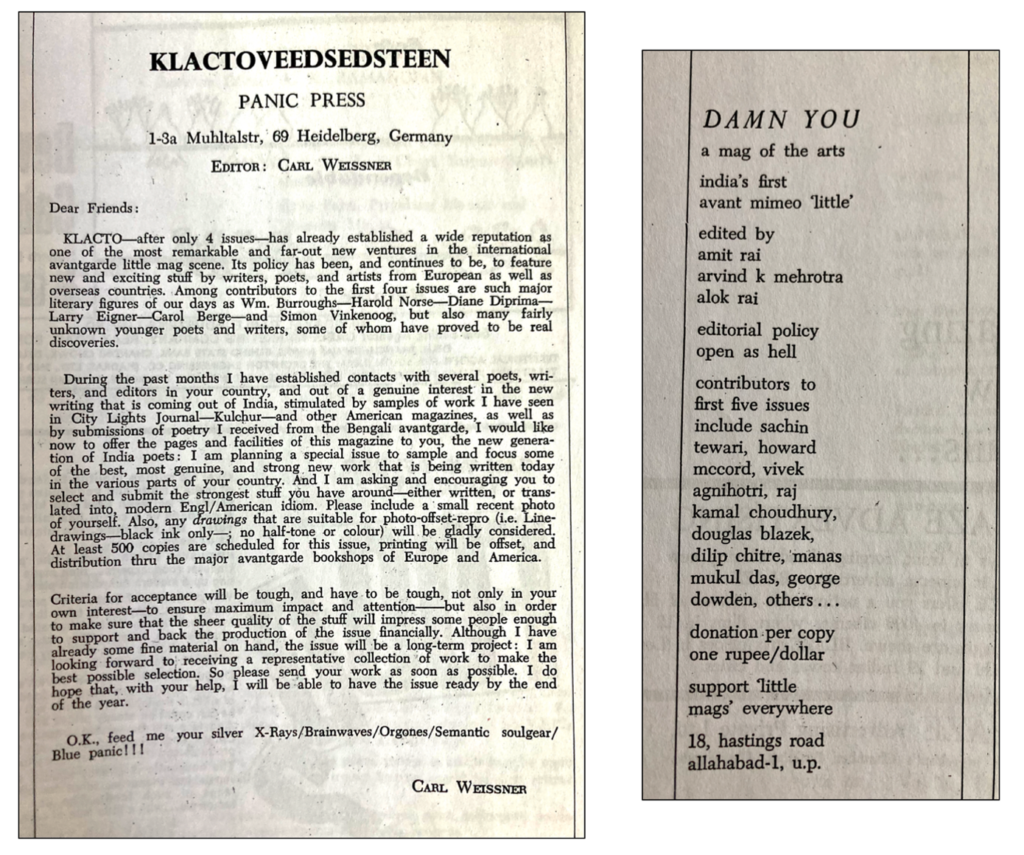

photographs, courtesy of Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Adil Jussawalla, Gulammohammed Sheikh.

Although Arvind Krishna Mehrotra is one of the most remarkable contemporary poets of India, he has consistently refused to be constricted by the obvious or prescribed signs of Indianness. One's location, "whether cultural, historical, geographical or fictive — is everything,"1 he writes, but it is shifting, constantly remade, and reinvented. If he can relate to the term "transnational," as he has himself suggested, it's perhaps in the sense that he ended up becoming an Indian poet by first camouflaging as an American one.2 To be sure Mehrotra delights in infuriating those who, within the increasingly Hinduized, nationalist cultural landscape of India, may feel provoked by the implications of such "irreverent" transnationalism.

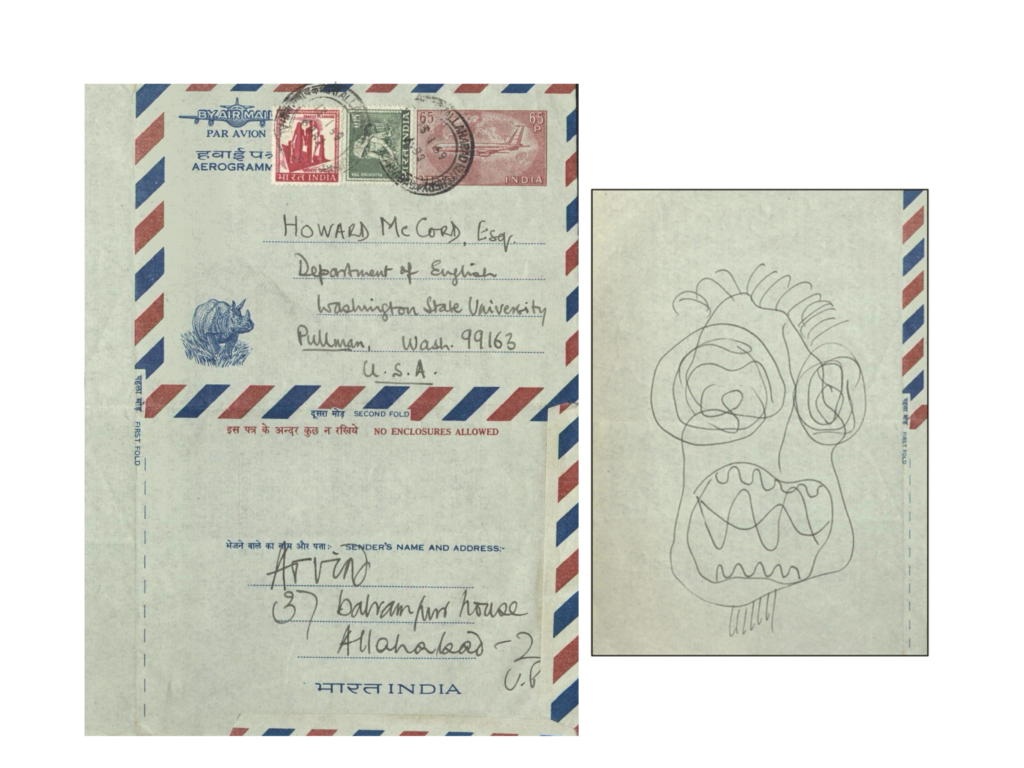

Even at 17, he harbored the illusion that he did not live in Uttar Pradesh, but New York City, and "to keep the illusion from shattering"3 surrounded himself with books and magazines from elsewhere, as well as with friends who lived in other countries. Many were poets, little mag contributors, and editors, and many lived in America. The letters and postcards he exchanged with some of them — and I will focus here on Mehrotra's correspondence with American poet and small press founder Howard McCord, then teaching at Washington State University in Pullman, — testify to how literary geographies ("the only country worth having patriotic feelings about")4 can run counter to "real" ones. They are also evidence of the extraordinary little magazine networks of the time, the underground traffic between American and Indian "communities of the medium" and the transnational friendships, conducted and staged through the channel of the little mag, that sustained the creativity of these writers.5

Mehrotra and McCord were each instrumental in mediating Indian and American little mag "material" to each other and to their respective audiences — however underground or counter-cultural. What their correspondence shows crucially as well, is that the traffics and the curiosity were, at least to a certain extent, reciprocal.

In India between the 1950s and the 1970s little magazines were flourishing in English, Marathi, Gujarati, Bengali, Hindi, and other languages. These magazines served as platforms for avant-garde writers and visual artists to connect with each other both within the Indian subcontinent,6 and outside it, with world writers and magazines. But if texts by Allen Ginsberg, André Breton, Vasco Popa, Henry Miller, or Jean Genet, as well as letters by James Laughlin, Eric Oatman, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, or Tom McNamara were published in little mags from Calcutta, Bombay, Delhi, Allahabad, or Baroda, poets such as Mehrotra or the Bengali Hungryalist Malay Roy Choudhury7 also materialized on the pages of countercultural little publications worldwide, many of which were published in New York or San Francisco in Evergreen Review, Manhattan Review, Kulchur, City Lights Journal, Salted Feathers, Intrepid, Ole', as well as other magazines.

Howard McCord played a key role in two extraordinary special issues of American little mags devoted to radical contemporary Indian voices. He edited the "Young Poets of India" issue of Measure 3 (from Bowling Green, Ohio in 1972), the genealogy of which can be found in his correspondence with Mehrotra. The "Poetry of India" issue guest-edited in 1968 by Carl Weissner for Intrepid (the mimeo magazine published by Allen de Loach from Buffalo, New York) also drew in part on McCord's own collection of manuscripts.8 Both issues were voluminous and long in the making. The Intrepid special issue was in fact initially supposed to be published in Klactoveedsedsteen, the Beat-influenced magazine Weissner published from Heidelberg, and as the postcard to Mehrotra below illustrates, the delays and impediments were of varying nature.

Mehrotra, in turn, published Douglas Blazek, McCord, and other American poets in his own littles brought out from Allahabad and Bombay. For those interested in the "Bombay Poets" and in Indian modernisms, the story of how Mehrotra started publishing little magazines, is by now quasi-legendary. It is revelatory of the chance encounters, the personal, alternative, even accidental circuits of circulation, publication, and funding on which so many of these provisional anti-establishment and anti-commercial publications relied — and it is too delightful not to retell. In 1965 in Allahabad, Mehrotra started to stencil damn you/ a magazine of the arts after having discovered the existence of Ed Sanders' Lower East Side-based publication Fuck you/ a magazine of the arts in an issue of the alternative newspaper The Village Voice.9 The copy of The Village Voice mentioning Sanders's little mag had been sent to Mehrotra's closest college friend, Amit Rai, whose uncle was studying on a Fulbright at Columbia.

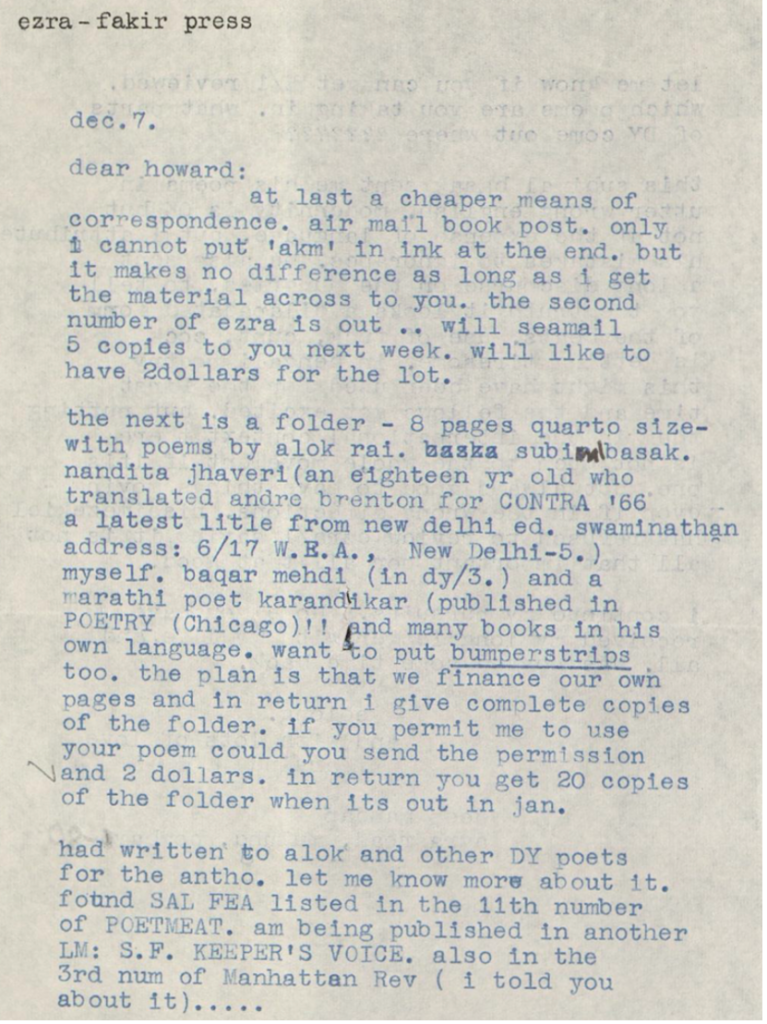

In the colonial-era bungalow where Rai's family lived and his father, a publisher, worked, they discovered a dusty Gestetner mimeograph machine which they quickly learned to operate. Soon enough, they were bringing out their own magazines. This is how Mehrotra's prolonged engagement with the American little mag crowd began. Within a few months, he was corresponding with some of the most significant figures of the "mimeo revolution," soliciting contributions for damn you and ezra/ an imagist magazine (the other little mag he founded in 1967 from Bombay), and publishing his poems in American littles before they were even published in India.10

Before taking a closer look at McCord's and Mehrotra's correspondence, let me offer one last snapshot of the connected networks, histories, and geographies of the little magazines of the time. McCord and Carl Weissner had both solicited contributions from Indian poets by advertising their forthcoming anthologies in Indian journals. Below is one such ad, published in a 1967 issue of Poetry India, the short-lived poetry magazine brought out by poet Nissim Ezekiel from Bombay. Weissner invites the "new generation" of modern Indian poets to send him "strong stuff," including drawings suitable for "photo-offset-repro," promising distribution "thru the major avantgarde bookshops of Europe and America." The same issue features an ad for Mehrotra's damn you announcing an editorial policy that is "open as hell." This ad showcases a list of Indian and non-Indian contributors, including McCord, notes the magazine's price in rupees and dollars, and closes on the tagline "support 'little mags' everywhere [emphasis added]."

The provenance of these two calls for contributors — the former in Heidelberg, Germany and the latter in Allahabad, India — published in the same Bombay journal, chart these transnational little magazine networks, and gesture towards other entangled East/West or North/South global histories as well. Mehrotra lived, wrote, and published damn you on a street — Hastings Road — named after the first Governor General of British India. This colonial history sheds light on how a poet from Allahabad in his late teens found himself writing in English and looking outside India for a sense of belonging, sustenance or community.

In newly independent India, writing and publishing poetry in English was far from obvious. Mehrotra has described himself and other modernist Indian poets in English as strugglers in a desert: struggling to clear a space in the Indian/world map of letters, to craft a lineage, and find an idiom. First because to nationalists and nativists alike — among those damned by Mehrotra — the alleged colonial language was like a "red rag to a bull," and also because, as described by poets AK Ramanujan and Adil Jussawalla, most Indian writing in English at the time took on a "starch-like," "dreadfully moralist" form. To poets like Mehrotra, the only available literary traditions in English felt obsolete, overblown, or useless. On the one hand the "divine abstractions" of Sri Aurobindo, and on the other the likes of Shelley, Keats, or Wordsworth, "the sort," notes Mehrotra wryly, "who have their monuments in Westminster abbey." This, he adds, "left the United States, a country just fifty yards down the road, at whose entrance stood not the famous statue but a bright red-letter box nailed to a neem tree."11

To a certain extent, it was precisely the precariousness or "outsiderness" of Mehrotra's position, his marginalization from the linguistic, cultural, and national(ist) mainstream, that accounted for his chosen Americanness and, more broadly, for his worldliness. It gave him and other Indian modernists the freedom to make his pacts outside national assignations and inherited communities, including literary ones, to invent a craft, an idiom and lineage — and to choose, as it were, by whom he wanted to be read and recognized.

***

If damn you's "open as hell" editorial policy could serve as a motto for many of these little mags, it's because it is suggestive of their anti-mainstream, anti-establishment stance ("oil and set the mimeo-machine like a machine gun" is another line taken from one of damn you's opening editorial statements). It also describes the defiantly inclusive, anti-canonical DIY ethos that some of these publications cultivated, in part by including artefacts of popular culture, such as stamps and advertising prospectus, paper masks, doodles, children's texts or drawings, and draft-like, seemingly unfinished texts.

More significantly perhaps, "open as hell" defines a mode of reading and writing. In one of his most dazzling essays — also a damning demolition of the state of literary criticism in India, and how it's besieged by questions of authenticity and Indianness — Mehrotra advocates for a way of reading "not in cork-lined rooms," but where "voices from outside can enter."12 These voices from outside, against all straitjacketing provincial and parochial impulses, have shaped the poet's disposition, and they continue to shape the palimpsestic, quotation-laced fabric of his texts. For instance, Mehrotra remembers that poems such as Ferlinghetti's "Underwear" and Ginsberg's "America" were an education in liberation and irreverence: "When Amit Rai and I first read these poems as teenagers we couldn't stop laughing. 'Women's underwear holds things up / Men's underwear holds things down.' Poetry was fun, as Wordsworth and Tennyson could never be. In poetry you could think the unthinkable and say it. I began to associate it with transgression."13

This openness to voices from outside subtends the two-way traffic between several American and Indian little magazine writers, editors, and networks in the 60s. More specifically, McCord's and Mehrotra's friendship, expressed in their long epistolary conversation with each other, was prompted and sustained by their curiosity for outside world voices.14

Mehrotra sent his first letter to McCord on October 24, 1966, from Bombay, where he had just enrolled at university. This was a direct response to McCord's letter, dated July 22, 1966, inviting manuscripts "from the most daring and concerned of young poets writing in English" (a call for work printed in Quest and The Illustrated Weekly, among other journals). "Without beating around the bush, you are a great man to realise the tremendous possibilities of Indian writing in English. And that too with an emphasis on the avantgarde," writes Mehrotra. The letter serves both to declare his keen interest in McCord's project, and to introduce himself and his little magazines: "littles in the true sense of the word" since they are "mimeo, small circulation and publish unheard of writers."

But the introduction quickly veers into something else. "The letter has been an outburst," writes Mehrotra in the closing lines. And this outburst seems, at least to some extent, strategic. The aim is to get noticed, leave one's mark: "in this letter I have made my existence noticeable." It is both the extraordinary confidence and the urgency of Mehrotra's voice, breaking onto the world (little magazine/avant-garde) stage, and demanding to be seen, heard, and published that I find striking. "WE DO NEED AN OPENING," he acknowledges. The appeal is pressing, and springs from Mehrotra's frustration with the literary scene in India, where "the avantgarde is given a kick in the guts, labelled 'influence a la Ginsberg et al.' and thrown out of the window."

For radical or avant-garde Indian writers confined to invisibility by the indifference of mainstream publishers, and by an establishment defined by Mehrotra later in the correspondence as "middle aged intellects in terrylene . . . a dozen bastards without teeth and claws," more little magazines "sprawling to be noticed all over the place" (italics mine) seemed the only alternative.

Incidentally, Mehrotra's frustration with the invisibility of Indian writers was also born from an impatience with the clichés and biases about India and Indian literature, and with the asymmetric ignorance of the West vis-à-vis the "East." If many American little magazine editors and poets seemed to acknowledge radical Indian poets as their "own," arguments about mimicry or belatedness that have continuously plagued Indian (and, more generally non-Western) modernisms also hangs over this correspondence. It can even throw some light on Mehrotra's ambivalence toward Ginsberg, and his alleged influence in India. In several letters to McCord, for instance, Mehrotra sharply criticizes the Bengali Hungryalists for looking like a "dilapidated form" of the Beats. "Modernity is OK," he advises, "but not at the expense of language ... use of fuck, cunt, cock is getting tiresome!" Even if the discovery of Ginsberg had been decisive,15 and although the Beat-centric avant-garde of Sanders's Fuck you/ a magazine of the arts had originally spurred his little mag publishing activity, Mehrotra fiercely asserted his and other Indian poets' independence. He refused to pay allegiance to any "school" or movement, and dismissed all powers or figures of consecration, however countercultural.16 He was also acutely aware of the exoticizing fantasies behind the Beats' fascination for India.

In his introduction to the Measure 3 "Young Poets of India" issue, Mehrotra voices his despair over what he calls the "culture of shortages" in India, and over the world's crass ignorance of the vast body of Indian literature. He also commends McCord's anthology for arousing interest in India's "new literature" rather than in the "hoards of farting maharishis." The special issue includes his acidic review of Ginsberg's Indian Journals, which opens with a derisive account of Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky's visit to (and visitation in) India, and the growing legend left in their wake: "some ten years ago there descended upon the Indo-Gangetic plain a man who since has passed into the Indian writer's permanent imagination." Ginsberg's journals left Mehrotra "unamused," even "exasperated." He portrays Ginsberg as "The Innocent Abroad," a "naïve American" who can only record a disconnected "mass of impressions" and Kodak clichés: "There is nothing that keeps the beggar woman, the corpse, the man performing rites, the sadhu and the cow...together, as something surely does, something more than a mysterious land."17

Ginsberg's exoticization of India also moved in one direction, disallowing the multidirectional exchanges that were central to Mehrotra's writing and publishing practices, and the plural worlds or ways of seeing by which India and Indian literatures have been shaped. In his 2012 essay "The Emperor has no Clothes," Mehrotra indeed argues for reading the (Indian English) poem "not as a delectable slice of reality which the critic . . . applies to his nose, but as a place, a construct, housing two or more ways of seeing; four-eyed; Chang and Eng." Ginsberg, in Mehrotra's account, seemed to have read India like a delectable "slice of reality," a supplier of ready-made motifs, "colorful gods" and strong sensations, oblivious to the multivocal cultural texture of the country, its many lineages and constellations.

In his letters, Mehrotra continuously urges McCord to enlist American poets to publish in his Indian mags, or to distribute, sell, and review copies of damn you and ezra. See how Mehrotra opens his second letter to McCord, sent barely 10 days after first initiating contact: "sent you 2 copies of EZRA. The other is to toss around. Let me know this immediately: will you be able to sell copies of ezra among your friends for a dollar each?" And again, on December 7: "let me know if you can get E/1 reviewed. which poems are you taking in. what parts of DY come out where?????" "Sorry for turning you into a salesman," he writes to McCord on December 26, while admitting that some letters must be sounding like those to "one's literary agent" (November 14, 1970).

To be sure, the tone is pressing, even commanding. The excitement of having an American "opening" is palpable. In another letter, Mehrotra notes that "everyone" — by which he means all the Indian poets he is in contact with — has heard of McCord's anthology, and "all are waiting for your yes's and no's." But the frustration and the impatience alluded to earlier surface again. Mehrotra, like other little mag editors, was constantly struggling financially, trying to devise means to continue publication and stay afloat. In many ways, Mehrotra's correspondence and friendship with McCord was a means to compensate for the "culture of shortages" mentioned above, as well as for the global asymmetries of funding, distribution, visibility, and consecration inherent in the (post)colonial world order.

These letters were Mehrotra's lifeline to the world and to world literature. From November 1966 to the early '70s, a steady stream of poems, magazines, books, and dollars were exchanged between the two poets. Lists of names and addresses — of writers, editors, magazines, even bookshops to watch out for, to contact, or send one's poems to — were shared as well, along with suggestions on which poets to include in the anthologies or journal issues in the making, and advice on authors to read (Bukowski, Ionesco, Octavio Paz, D.H. Lawrence, Dylan Thomas, and Michael Fraenkel, among others). The two poets asked for each other's opinion on their respective texts, and exchanged personal and literary news ("how is the poetry growing? what's the yield per acre man," wrote Mehrotra to McCord on March 6, 1970). They also shared their disappointments and their successes (in the case of Mehrotra, poems of his that had been accepted in The San Francisco's Keeper's Voice, New York Quarterly, University of Tampa Poetry Review, outcast, Poetmeat, TRACE, Camels Coming, Delos, or Kayak).

The poets' exchanges are in large part driven by the desire to get material across, as Mehrotra suggests in the letter above: the means of correspondence (airmail, seamail, etc.) make no difference "as long as I get the material across to you." Incidentally, other less literary material was trafficked between transnational borders! In 1966, Mehrotra sent McCord 100 greeting cards with Indian gods to sell in the US. A few months later McCord wrote to say that this being "a bad, broke month... (Even in Affluent America!)" — note the irony here, clichés about India in America being mirrored by clichés about America in India —, he couldn't include a "buck" or two with his letter. Although McCord was unable to sell the postcards, he suggested an alternative source of funding, already successfully experimented by Malay Roy Chaudhury. The latter had apparently devised a stratagem to fool the post-office and include charas (the local name for cannabis) between the pages of his little magazines.

***

Despite the asymmetries and hierarchies of global North/South cultural traffics, and as both the tone and content of Mehrotra's letters make clear, Mehrotra and McCord carried on a conversation between equals, so to speak. The Indian poet claimed his place in the world geography of letters as a full participant in an international little magazine network. To a certain extent, Indian and American little magazine communities and countercultural publications carried on "mutually generative" — and, if we insist on keeping the paradigm of influence, mutually influential — connections at the time.18 Mehrotra, like other Indian modernists, was not satisfied with being at the peripheries: "damn you eating the corners of literature" is another fantastic line from his little magazine. That is one of the many reasons why these magazines are fascinating to study. In their perishable pages, centers and peripheries are realigned or eroded, along with our understandings of what counts as local or worldly, ephemeral and memorable, minor and canonical, or trivial and political.19

Laetitia Zecchini is a tenured research fellow at CNRS (Paris). Her research interests include contemporary South Asian poetry, Indian modernisms, postcolonial print cultures, and the politics of literature. Her latest book is the coedited volumeThe Form of Ideology and the Ideology of Form: Cold War, Decolonization and Third World Print Cultures (2022).

References

- Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, "The Emperor Has no Clothes" (Partial Recall, Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2012), 168.[⤒]

- Mehrotra may in fact have adopted different camouflages and idioms during his life (as an American Lower East Side poet, as a "French" poet, as a "Bombay poet", etc.) [⤒]

- Mehrotra, "Mela" (Partial Recall), 113. [⤒]

- Mehrotra, "The Writer as Tramp," Translating the Indian Past (Ranikhet: Permanent Black, 2019), 178. Fellow Marathi-English poet, little mag founder/contributor and close friend of Mehrotra, Arun Kolatkar was also fond of the following line by Marina Tsvetayeva: "Orpheus exploded and broke up the nationalities so wide that they now include all nations, the dead and the living." [⤒]

- This piece stems from my ongoing research on Indian modernisms, little magazines and the "Bombay poets." For open access references see Laetitia Zecchini, "Translation as Literary Activism: On Invisibility and Exposure, Arun Kolatkar and the Little Magazine 'Conspiracy", Literary Activism (2017) and "'What Filters through the Curtain': Reconsidering Indian Modernisms, Travelling Literatures and Little Magazines in a Cold War Context", Interventions 22, no. 2 (2020), 172-194.[⤒]

- It's a sense of these effervescent transactions across artistic, linguistic and generic barriers that we wanted to give in the special issue of "The Worlds of Bombay Poetry", eds. Anjali Nerlekar and Laetitia Zecchini, Journal of Postcolonial Writing 53 (2017): 1-2, which includes critical essays, memoirs, letters, interviews with poets, artists, and little mag editors, as well as many visual documents.[⤒]

- Anti-elitist and provocative, the "Hungryalist movement" took the Bengali literary world by storm in the '60s. Ginsberg and McCord, who had met poets of the group when they travelled to India (in 1962 and 1965 respectively), corresponded with Malay Roy Choudhdury and were instrumental in having Hungryalist texts and manifestoes published in various little mags in the US. A special Salted Feathers "Hungry!" issue was edited by Dick Bakken (March 1967).[⤒]

- The issue also included excerpts of Ginsberg's Calcutta Journal, poems by the "bengali [sic] poets of the Hungry Generation," "bengali [sic] poets of the Krittibash Group" (such as Sunil Gangopadhyae), and "poets from bombay, delhi, Allahabad" (including Arvind Krishna Mehrotra, Arun Kolatkar, and Kamala Das).[⤒]

- The June 17, 1965 issue of Village Voice for instance has an interview with Ed Sanders. Sanders is described as operating a "rickety mimeograph machine" from a Lower East Side bookstore that was turning out "a legendary revolutionary organ which has been euphemistically tagged (by the uptown glossy magazines) as Love You."[⤒]

- Mehrotra's texts were eventually also published in Indian little magazines of the late 60s and the 70s, such as the Gujarati Kruti, or the Baroda-based English little mag Vrishchik, founded by the two celebrated modernist visual artists Bhupen Khakhar and Gulammohammed Sheikh. [⤒]

- See Mehrotra's exquisite autobiographical essay "Partial Recall" for details about the founding of damn you (in his eponymous collection of essays, 2012).[⤒]

- "The Emperor has no Clothes," Partial Recall, 161. "Voices from outside" such as the Beats and the surrealists, but also voices of the past, including many South Asian voices. See Mehrotra's translations/transcreations of Kabir (Songs of Kabir, NYRB Classics, 2011), and Ghalib (Ghalib: A Diary, New Walk Editions, 2022). [⤒]

- See Laetitia Zecchini, "We were like Cartographers, Mapping the City: An Interview with Arvind Krishna Mehrotra," with various illustrations from damn you & ezra, Journal of Postcolonial Writing (2017), 190-206. [⤒]

- This correspondence is part of the Hungry Generation Archive (MS47, Box 1), Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections at Northwestern University. [⤒]

- See Mehrotra's earlier quotation about associating poetry with transgression. Mehrotra has also acknowledged that the Beats had purged him of nationalist feelings. "'Go fuck yourself with your atom bomb' Ginsberg says in 'America.' Now if an American poet could say this of America and its bomb, I could certainly say it of India" (Zecchini, "We were like Cartographers," 194).[⤒]

- The editorials (called "statements") of damn you and ezra often present themselves as declarations of independence and assertions of difference: "we are men, breathing, and we breathe for ourselves, not for the age we live in" (damn you 6, 1968). [⤒]

- Mehrotra, "The Emperor has no Clothes," 172.[⤒]

- The expression "mutually generative" comes from Steven Belletto's essay who convincingly argues that it was Ginsberg's letters to Ferlinghetti from India (in which he included manifestoes and poems by the Hungryalists) that inspired Ferlinghetti to start a new little mag, which would become City Lights Journal, meant to showcase the contemporary international avant-garde. See Steven Belletto, "The Beat Generation Meets the Hungry Generation: U.S.-Calcutta Networks and the 1960s 'Revolt of the Personal,'" Humanities 8, no. 3 (January 2019): 1-17). In my book on Arun Kolatkar — where I devote several pages to the Beats in Bombay, and to the Hungry Generation — I also emphasize the reciprocal impact between the Beats and the radical fringe of Indian poets. See Laetitia Zecchini, Arun Kolatkar and Literary Modernism in India, Moving Lines (London: Bloomsbury, 2014). For a history of the Hungryalists, see Maitreyee Bhattachharjee Chowdhury, The Hungryalists, the Poets who Sparked a Revolution (London: Viking, 2018). [⤒]

- This is a point I try to make at length here: Laetitia Zecchini "'Archives of Minority': Little Publications and the Politics of Friendship in Postcolonial Bombay," South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies (2022).[⤒]