My Struggle, vol. 6: Dan, November 20

Somewhere over the Atlantic

Dear friends,

It was anxiety. Now, despair. "My basic feeling is that of the world disappearing, that our lives are being filled with images of the world, and that these images are inserting themselves between us and the world" (838).

Knausgaard writes this in the middle of a long paragraph, one of many in which he explains why Hitler went to war and tried to exterminate the Jews. We lose the world, he writes, when we lose the absolute: religion, mythology, the irrational, faith, death, emptiness, darkness (837). We lost the absolute when the world became homogenized through mass production, when reason came to mean, universally, profitability, when a globalized news media flattened what it described into an endless uniformity. Vacuum-sealed steaks, sterilized funeral parlors, and CNN flood Knausgaard with yearning for what he calls reality, from which he feels remote. It was this same remoteness, this yearning for authenticity, for the absolute, that he thinks led to the Holocaust.

This essay—more than four hundred pages long—is called "The Name and the Number." The name is a pointsman switching us from the track of ideas, abstraction, fiction, to things, specifics, reality. If the number is quantitative, the name is the portal to the qualitative, to the individual, to the face, to feeling, and, so, to the absolute. Modernity brought enumeration. Industrialization brought masses to cities. We became remote from reality. Six million Jews were faceless animals. "It was the fall of the name into the number" (842).

*

There is a dive bar on the outskirts of Bloomington, Indiana called the Office Lounge. One night not long ago, I stood amid the crowded tables with a microphone in hand. I had prepared ahead of time. At home, I'd peeled on my girlfriend's black fishnet stockings under my teensy Forever 21 black cutoff booty shorts. I wore my little tee that says Sweet and has a picture of a peach. Masha did my eyeliner. I slipped into my Chuck Taylors, bedazzled in rhinestones. So, when I stood with one foot on a chair waiting for the opening note of Bonnie Tyler's "Total Eclipse of the Heart," I was ready.

I guess what I'm trying to say is: I've touched the absolute.

*

If we've lost the world, there can be no realism, that vexed aesthetic category. The loss of realism hurts Knausgaard. "We have made a myth of reality," he writes, "but unlike the people whose lives were determined by a mythological understanding of the world, we are unaware of it" (664). Our myth has been made, in part, by newspapers. "The newspapers are full of...events deviating in some way from the norm, and our reading about them there lends them a kind of fixedness they don't have in real life, where they are over the minute they occur and no one who witnesses them can quite grasp what actually happened. This fixedness is a fiction, but we understand it to be reality" (656). The thoroughness of the divorce between the experience and the representation of reality has created a collective psychosis. It's not just the news. Knausgaard argues that the use of any literary techniques in narrative—character, plot, metaphor—deforms reality. To answer a question Stephanie asked early in this correspondence: it's not simply that fictional representation can't jettison Bildung, it's that all representation threatens to be fictional. The notion of a true realism, a writing that at its asymptote would be, like Borges's maps, reality itself, is a kind of wisp for Knausgaard that he's ever chasing.

My Struggle is Knausgaard's attempt to win back reality. His method, as Marit argued, is to train his, and our, capacity for attention. The images Knausgaard laments in the quote I opened with are the screen images that Marit identifies as eroding this capacity. The world is not yet unrecoverable: "it was not reality that had vanished, but my attention toward it" (414).

Attention against despair: this is self-help, self-care, yoga, mindfulness, meditation, David Foster Wallace's Kenyon commencement speech packaged after his death into a checkout aisle impulse buy, This is Water—practices that save so many from unnecessary suffering and, at the same time, too often redirect the sins of capital onto the body of the individual. If we apotheosize these practices, if we treat them as the last grasp for the absolute, they become a kind of tacit class warfare that in Knausgaard is also pretty fucking straight and white.

I say this as someone who loves Bonnie Tyler as much as Ingmar Bergman. Earlier on this flight, I watched Paul Schrader's First Reformed, a remake of Bergman's Winter Light, among my very favorite movies and one that requires deep attention as it pursues the absolute in the very sense of Knausgaard's lexicon amid the banality and iniquity of everyday life. A pastor whose counsel fails to prevent a parishioner from killing himself in despair at some global threat (China getting the bomb, climate change) then, himself, faces his own existential despair. First Reformed ends with Ethan Hawke, the pastor, wrapping himself in barbed wire under his vestments and, as the camera slowly spins, bloodily, dizzily, makes out with Amanda Seyfried. This is sublime Knausgaardian art.

But, for all I relish tender acts of attending to text, goddamn do I love images, gifs, memes. When Knausgaard locates the source of our despair in our loss of aesthetic attention, he is making an inconsequential bourgeois habit universal. Fewer and fewer people enjoy curling up for long, uninterrupted sessions with a physical book. More by far read on their phones or tablets or ereaders or listen to audiobooks. Most don't read at all. This is by no means obviously bad. The history of technology shows that attention always changes and that each new technology gives just as it takes away. To lament the losses at any given time as the losses of the absolute is to take up one's arms on behalf of a rearguard battle not for the absolute but for a passing kind of classist taste.

*

Stephanie, many letters ago, argued that Knausgaard's writing is "completely opposed" to the ideology of the Swedish middle class. He feels constrained by the ideological norms of the day: gender neutral pronouns, pro-immigrant sentiment, the feminization of men, all of which he feels are mere moral dicta that serve, in fact, to distract from, and thus reinforce, class inequality. Omari condemned him for this, Marit praised him. (Late in "The Name and the Number," Knausgaard claims that the Nazis, aspiring as they were for nationalism and the distinction of German identity, imagined Jews as embodying a globalist, homogenizing sameness; and he notes that, in Shoah, a functionary of the Holocaust describes Jewish language "like animal noise, bird noise" (813). The resonant echo of Knausgaard's own characterization of immigrants in Sweden earlier in Book 6 in the much-discussed playground scene ironizes that earlier moment. The parallels between what he says the Nazis felt about Jews and what he feels about immigrants are too obvious, suggesting that Knausgaard knows his positions are heinous. This complicates, I think, both Omari's censure and Marit's apologia.) Knausgaard's defense of attention commits him to the same error he accuses his peers of committing: a critique of the middle class that is, in fact, a devoted effort on its behalf.

*

Knausgaard's writing is driven by a "powerful urge to rise out of such fusty triviality into the clear, piercing air of something immeasurably greater" (413). His genius in My Struggle is to make fusty triviality profound: exploding sausage, the little card reader ejecting a receipt. But many not straight, not white, not upper-middle class folx have found in the proliferation of images, and the intelligence that this proliferation has created, love, levity, and, yes, access to the absolute.

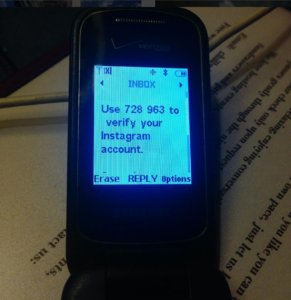

For my part, I'm very white, upper-middle class, kinda straight, and, I'll add given the topic of this letter, half-Jewish. I have only belatedly risen out of fusty triviality into something immeasurably greater in the piercing air of Instagram. I know the limits of my will—and, as a Pisces, I am ineluctably drawn to shiny things—so I use a flip phone. But last summer, on a weekend trip upstate to Storm King, Masha opened for me, on her iPhone, an Instagram account.

Here's me at a Takashi Murakami show in Fort Worth.

I find pleasure in My Struggle's epic pursuit of realism. But the real project, I think, is much more interesting than the one Knausgaard theorizes in Book 6. We've spent countless letters doing a better job than he himself does explicating its richness.

In Søren Kierkegaard's emo taxonomy of despair, Sickness unto Death, a sequel to his Concept of Anxiety, he describes the many ways we act out against "the fundamental lack of meaning" Knausgaard feels at the heart of his project (414). The only way out of despair, argued Kierkegaard, was through faith in God. Because there is no god, we are trapped with the sickness.

Knausgaard misidentifies the source of our despair, the cause of the Holocaust, his own aesthetic theory, and thus the way out. It's not that realism has become almost impossible. It's that realism, the representation of reality, is all around us all the time, whether sacralized by Knausgaard's extended description of a pacifier or its many-filtered expression in countless pixels on Instagram, vaulting me from this surreal trash world to the Icarian heights of the absolute.

#love from 33,000 feet,

Dan

ALSO IN THIS SERIES:

The Slow Burn, v.2: Welcome Back

The Slow Burn, v.2: An Introduction

My Struggle, vol. 1: Cecily, June 6

My Struggle, vol. 1: Diana, June 9

My Struggle, vol. 1: Omari, June 14

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, June 17

My Struggle, vol. 2: Omari, June 24

My Struggle, vol. 2: Cecily, July 1

My Struggle, vol. 2: Sarah Chihaya, July 5

My Struggle, vol. 2: Dan, July 12

My Struggle, vol. 2: Diana, July 16

My Struggle, vol. 2: Jess Arndt, July 18

My Struggle, vol. 3: Omari, July 25

My Struggle, vol. 3: Ari M. Brostoff, August 1

My Struggle, vol. 3: Dan, August 4

My Struggle, vol. 3: Jacob Brogan, August 8My Struggle, vol. 3: Diana, August 12

My Struggle, vol. 4: Katherine Hill, August 25

My Struggle, vol. 4: Omari, September 1

My Struggle, vol. 4: Dan, September 2

My Struggle, vol. 4: Diana, September 15

My Struggle, vol. 5: Omari, September 27

My Struggle, vol. 5: Diana, October 3

My Struggle, vol. 5: Dan, October 13

My Struggle, vol. 6: Omari, September 25

My Struggle, vol. 6: Dan, September 28

My Struggle, vol. 6: Stephanie, October 5

My Struggle, vol. 6: Cecily, October 9

My Struggle, vol. 6: Emily Tamkin, October 10

My Struggle, vol. 6: Diana, October 15

My Struggle, vol. 6: Rachel Greenwald Smith, October 23

My Struggle, vol. 6: Katherine Hill, October 26

My Struggle, vol. 6: Omari, October 31

My Struggle, vol. 6: Jess Arndt, November 6

My Struggle, vol. 6: Joshua Keating, November 12

My Struggle, vol. 6: Marit MacArthur, November 13