Leaving Hollywoo: Essays After BoJack Horseman

"Hey, you see those people?" BoJack says to ten-year-old Sarah Lynn at the start of BoJack Horseman's third episode, looking out at the live studio audience of Horsin' Around. Sarah Lynn is curled up in a ball under the set's kitchen table in pink pajamas. "Those boobs and jerkwads are the best friends you'll ever have," he tells her, deadly serious. "Without them, you're nothing . . . Your family will never understand you, your lovers will leave you or try to change you, but your fans, you be good to them, and they'll be good to you."

BoJack offers Sarah Lynn a screwed-up idealization not just of fame, but of friendship: friendship is a promise of unending reciprocity, a salve for the chronic failure of familial and romantic relations, and a utopian respite from loneliness and self-doubt.1 BoJack Horseman's writers are ribbing BoJack for his toxic incompetence as a father figure, but the whole show turns out to be a six-season process of gutting and renovating this worn-out definition of friendship, reworking it to reflect the support systems contemporary Hollywoo demands. In short, BoJack Horseman is a show about friendship.

In sitcoms, friends guarantee the comfortable status quo, but unfortunately BoJack outlives Horsin' Around. His fans — the best friends he thought he'd ever have — abandon him, and BoJack Horseman tracks his repeated attempts to manufacture self-worth in their absence.2 The series, which appears at first to be a sitcom, bends the format out of shape: things are definitely not always okay at the end of twenty-five minutes. When they're not, it's often because a friendship has failed. Friend trouble undercuts BoJack's happiness more deeply than any romance: he abandons Horsin' Around creator Herb Kazzaz and plunges into narcissistic careerism; when his roommate Todd rejects him he heads on a bender that kills Sarah Lynn; after his half-sister Hollyhock cuts ties he heads on another bender and nearly drowns. Friends don't always understand you, do leave you, and do try to change you.

If BoJack figures out how to assemble his own sense of self, it's through repeatedly screwing up and gluing back together his relationships with friends. This process involves not just plot devices and dialogue, but also the show's genre identity, animation techniques, representations of labor and romance, and use of setting. The first season of the show introduces us to a handful of debatably good, not necessarily likeable people who definitely do not yet love each other. Over time BoJack, Sarah Lynn, Diane, Mr. Peanutbutter, Todd, and Princess Carolyn become friends.

Genre

BoJack's genre is vital to its friendships. In its early days, BoJack feinted as a classic sitcom: each episode was a self-contained capsule, storylines were crafted to bear a heavy load of jokiness. Friendship lends itself well to this format.3 The prototypical friendship is stable, static, and undramatic — able to contain the turbulence of two separate lives. Like the sitcom, it has an episodic temporality: routine lunch; "drinks soon?"; the drum of text messages. It's an unending process of catching up, keeping apace of one another's plots.

But BoJack is not just a sitcom; its friendships aren't like this. The show comes out as a long-form dramatic narrative in the middle of the first season, when Herb Kazzaz, dying of cancer, denies BoJack the forgiveness he needs in order to shake off his complicity in the network's homophobia. Characters are concerned with their own long-term development. Occasionally relationships rupture. As Stephanie Foote notes, BoJack is left clinging to the comfort of sitcom logic while his friends complete their narrative arcs and move on.4

Perhaps more than any other type of relationship, friendship needs shared experience, a fabric of common associations, to gather emotional intensity. Friendships take time. They're poor investments for dramas that promise viewers a quick emotional payoff. Sex and romance flood dynamics with tension and supply plots with stakes. By contrast, friendship's beginnings are often banal and lacking in erotic charge. Without predictable milestones, friendship is harder to mine for legible plot points.

BoJack's genre flexibility gives it tools to handle friendship's looseness. The show's jokiness gives it enough independence from drama that it can center friendships; its commitment to weighty long-term plotlines gives these relationships enough duration and mutability that they produce affect. BoJack's friendships become the show's emotional substance because daily encounters slowly ferment into intimacy.

Animation

Relationships become more complicated as BoJack's animators get better at rendering complexity. As characters learn how to express their feelings together, their bodies become more capable of physical expression. Animators slowly pick up the muscle memory for making any face express any feeling at any angle, getting more practice at drawing some characters than others.5 It's like learning to recognize someone from the way they walk: the characters we spend more time with grow to have more sides to them.

The fluency of body language grows season to season. Early on, bodies use a limited, shared vocabulary of standard gestures: speaking characters wave their palms around and sometimes use their index fingers to announce an idea or point something out. They arbitrarily shrug or cross their arms, as if they simply need to be moving so you know to watch them when they speak.6 At first, LA feels like it's made of tableaus: only later do characters learn to live in their world, fluidly extending their bodies through the third dimension. By Season 6, hands and heads articulate depth through micromovements. It feels like everyone can speak more freely. Characters glow around the edges. When BoJack dances with Princess Carolyn at her wedding, the conversation hinges on a choreography of contiguous microshrugs and head tilts.7

The series ends with a full minute and eight seconds of fidgeting. Diane tells BoJack she's cutting him out of her life. They run out of things to say. He looks at her, and she looks up at the night sky, arms crossed. He looks down, and then up. She looks slightly left, and then slightly right, as if glancing between off-screen configurations of stars. He does the same, just barely hanging his head. They blink in unison. Her mouth opens and she glances at him quickly without turning. She quickly looks down and away, furrowing her brow. Still looking up, he closes his eyes tight.

Gesturing is real-time evidence of one character's presence resonating with another character. Fidgeting releases televised intimacy from dependence on words or touch: fidgeting shows characters negotiating having bodies alongside one another. A big part of friendship in the show is being in the presence of someone else fidgeting.8 A good friend tacitly knows how to match the tempo and cadence of your gestures and speech. It feels good to soak up familiarity.

Diane and BoJack's microgestures choreograph my eyes, too: I focus on each in turn, present to Diane's aloneness and then BoJack's. I find myself feeling out what each has meant to the other. This intersubjective relay is operated by a small handful of black pixels. The look Diane gives BoJack is comprised of a tiny black dot — Diane's pupil — moving about two millimeters to the right on my laptop screen. This tiny movement invokes the full ambivalence of Diane's tenderness for BoJack; it shows how densely woven their dynamic has become.9 "To intimate" is the sparsest of communication, the most economical mode of telling, as Lauren Berlant points out.10 Intimate relationships depend on quiet gestures. Conversation boils down into densely nuanced shorthand. Familiarity is a process of reduction.

Economy

Friendship is a mode of alliance-formation under capitalism beyond typical kinship. Being a good friend signals a willingness to exceed strategic self-interest and form anomalistic alliances. But it's also a bond that can be leveraged to extract more from the system. Often it's both. In BoJack Horseman, friends give one another leg-ups in the hierarchy of Hollywoo, and console one another when the cutthroat industry diminishes their mental health.

Many of the friendships in the series start out as economic ties. Princess Carolyn is BoJack's agent. Diane is a ghostwriter thrust upon BoJack by his publisher. Todd is his freeloading houseguest, Sarah Lynn his (ex-)colleague, Mr. Peanutbutter his (ex-)competitor. BoJack Horseman is about people who employ one another, do emotional labor within that capacity, and subsequently develop meaningful bonds.

"Friend" is the loosest, the most amoebic of the terms we have for how we relate to each other.11 The relationship lexicon distinguishes between platonic and non-platonic, kin and non-kin, personal and professional. In BoJack, characters often slip and slide through this taxonomy. Princess Carolyn and Diane's friendships with BoJack begin as the begrudging stalemate that lets a relationship continue when one party's romantic feelings aren't reciprocated. Friendship is tensile, capable of bearing ambivalence or the near absence of feeling. It's just a hazy commitment to ongoingness. Nonetheless, in BoJack's universe, it's your best bet. Everyone's parents are bad. No early-season romances last. Friendship can bear the tides of affection and alienation between characters over six years of plot.

But the show jettisons its optimism about friendship toward the end in favor of something more explicitly binding. Nearly everyone winds up in a secure, monogamous, relationship with a character from outside the friend group: Diane and Guy, Princess Carolyn and Judah, Todd and Maude. In the finale, BoJack asks Diane for some advice around commitment: "How do you learn how to trust it? To trust the happiness?" Here "happiness" is a metonym for her marriage to Guy. I agree with others in this cluster that the ending relies on closure-free ambiguity. But in the most cynical light, the show becomes a parable about moving through the tribulations of friendship as a training ground for the permanence of the dyadic domestic family form. The show's two key women find love while BoJack is in prison, and he emerges to find them unwilling to indulge the messy intimacy of his friendship. Friendship is the meat and potatoes of the show's emotional life, but the finale also depends on the marriage plot's eventfulness.

Place

In BoJack Horseman, friendship happens by the pool. Todd ends his friendship with BoJack in front of it; Mr. Peanutbutter saves BoJack from drowning in it; BoJack and Diane meet for the first time behind it. At parties, the pool gathers a crowd. Friends corner one another for respite from clumps of partygoers; friendship takes place when characters escape from clout-seeking industry strangers and get real with each other.

These intimate moments rely on the background hum of Hollywood social climbing: when Diane and BoJack first meet, she apologizes for being awkward at social gatherings.

They turn their back on the pool. Looking out over the Hollywood sign, she tells him he's responsible for his own happiness. Friendships begin with sharing the feeling of wishing everyone else would go away. It turns out that the audience isn't your best friend, but the backdrop against which friendships are made. The show self-consciously uses the pool as a prop in a modern Narcissus myth. The medium of self-reflection is a suburban status symbol. (In the first season, BoJack recounts his life to Diane in his office, where a horse version of David Hockney's Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures) hangs behind his head.)12 Friendship happens by the pool because, for BoJack, it takes place on the periphery of self-absorption. But some good self-reflection gets done here: BoJack finds Hollyhock sitting on a recliner, chucking lit matches into the pool. They stare into the water, watching them fizzle, and chat; she asks him whether feelings of worthlessness go away as you get older. In a strange inversion of the ruthless cynicism BoJack feeds Sarah Lynn early in the series, he lies, kindly.

Watching is the format of friendship in BoJack. Rather than face-to-face, friendship's geometry is triangular: you and another person sit next to each other, looking at a third thing.13 Sitting next to each other offers vulnerability-averse characters like BoJack a means to relate to someone obliquely, without the pressures of head-on confrontation. It's the "this" that lets him say, "this is nice," and keep being together when saying anything else becomes impossible, as Cushman and Foote discuss. For Stark and O'Rourke, it makes "the unsayable sensible." (Meanwhile, watching BoJack is a mode of being together for them.) Friendship, here, is about being in an audience.

Near the end of the series, BoJack, Diane, and Princess Carolyn huddle in BoJack's office in the wings of the Wesleyan theater. BoJack confesses his involvement with Sarah Lynn's death, devastating his friends. He leaves them briefly, joining his students' party in the theater to announce their end-of-year superlatives. Princess Carolyn and Diane stand in the foreground, watching BoJack speak to a whooping audience. They fidget, sometimes looking at him, sometimes looking down. They alternately smile despite themselves at BoJack's joyfulness with his students and hang their heads, remembering what they've just learned.

I look between Diane and Princess Carolyn as each fidgets in turn. BoJack's speech draws my attention to the background. I consider Diane's ambivalent feelings for BoJack, and then Princess Carolyn's — two different dynamics, both complex. I sit with BoJack's affectionate relationship to his newfound audience of college kids. Though his friendships with Diane and with Princess Carolyn have followed parallel plotlines, here they merge. For Diane and Princess Carolyn, BoJack is suddenly the common watchable object that brings them together, like the Hollywoo sign or the pool. He's found an audience of friends to fill his fans' vacancy — but it's not about him anymore.

Lily Scherlis (@lilyscherlis) is a PhD student in English at the University of Chicago and Associate Editor at Chicago Review. She has written about the social history of social distancing for Cabinet.

References

- Friends do play some of these roles in the show, as in life. But the show's arc makes it clear that friends can hurt you and will not save you. BoJack exemplifies Heather Love's argument that the idealization of friendship — even within queer studies — has "flattened the real affective complexity of this bond." See "The End of Friendship: Willa Cather's Sad Kindred," in Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 2007), 75.[⤒]

- Most of his fan base dissolves as Horsin' Around becomes a relic of the 1990s; more attrition builds from scandal to scandal, leaving BoJack with name recognition and a small handful of toxic, obsessive followers (for instance, the president of his fanclub, who jealously keeps a scrapbook with the home addresses of BoJack's exes).[⤒]

- The sitcom wasn't always devoted to televised friendships; Seinfeld (1989-1998) and Friends (1994-2004) reoriented the genre from the usual settings at home (like Horsin' Around) or at work (quintessentially, The Office). Jeremy G. Butler, The Sitcom, Routledge Television Guidebooks (New York: Routledge, 2020), 81.[⤒]

- Character development and friendship are hard to separate. Marta Figlerowicz has written about how characters come to depend on others for knowledge of themselves: see Spaces of Feeling: Affect and Awareness in Modernist Literature (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017).[⤒]

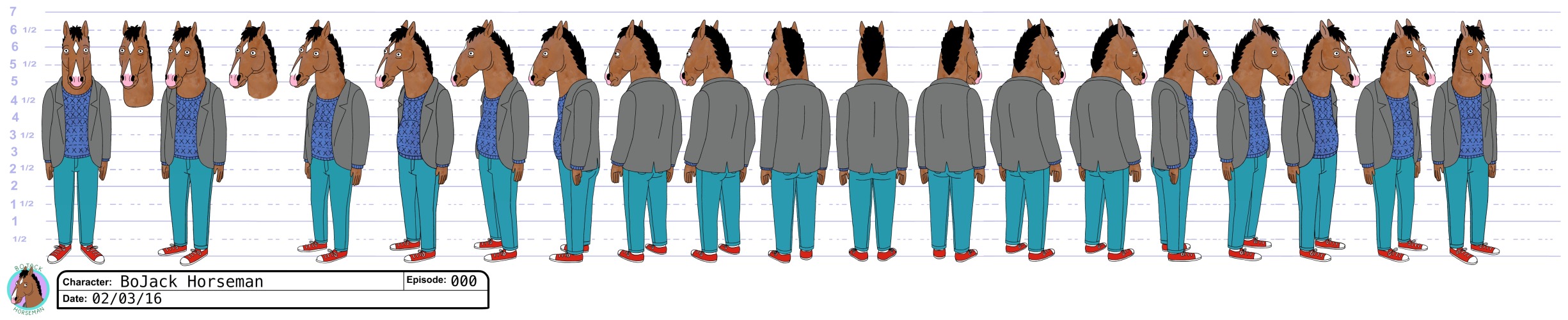

- This process is embedded in animation protocol: when animators design a character, they draw a model sheet, which displays that character against a height chart facing all different directions; it's like a police line-up for different sides of a person. Model sheets include more angles if a character appears more often, because inconsistencies will be noticed. Tom Bancroft, Creating Characters with Personality (Potter/Ten Speed/Harmony/Rodale, 2016), 55.[⤒]

- Partly it's because of literal production constraints: they had to make the six hours of animation comprising the first season in thirty-five weeks. Meanwhile Lisa Hanawalt, the illustrator directing the production studio, had never done any animation before, and had to learn how to deal with motion on the job. Season Two is already more graphically nuanced. Chris McDonnell, "How BoJack Horseman Got Made," Vulture, September 4, 2018.[⤒]

- Grace Lavery has written about what's erotic in the lines and ink of BoJack's characters: "Bojack Horseman, the Romance of Depression, and Our Fuckable Furry Friends," November 25, 2019. Ben Carver, in this cluster, notes how cartoon blankness leaves room for a wider range of projective identifications.[⤒]

- We can read gestures between friends with more openness than between lovers. For Foucault, discussing Lillian Faderman's writing on female friendship, analyzing a relationship between men or women within the frame of friendship, rather than attempting to diagnose sexuality, lets "the relationship manifest itself as it appear[s] in words and gestures." See "Friendship as a Way of Life," in Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth. Edited by Paul Rabinow. Translated by John Johnston (London: Penguin Books, 2000), 138.[⤒]

- Longer relationships tend to produce more feelings of all stripes: As Sianne Ngai has recently noted, following Freud, "the copresence of negative and positive affects strengthens the overall intensity of our attachment to an object." See Sianne Ngai, Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020), 23.[⤒]

- Lauren Berlant, "Intimacy: A Special Issue," Critical Inquiry 24, no. 2 (1998), 281.[⤒]

- As Stark and O'Rourke know, intense non-romantic rapport between men and women feels transgressive and hard to express. For Foucault, the vocabularies and institutions that let us name and thus stabilize how we relate to one another can only accommodate certain configurations of age and gender. Friendship is one way to narrate relationships that fall through the gaps. See "Friendship as a Way of Life." [⤒]

- See Deborah Vankin, "David Hockney's $90.3-Million Pool Painting Obliterates Auction Record for Work by a Living Artist," Los Angeles Times, November 17, 2018. [⤒]

- In part this is probably because it's simpler to animate conversations when characters face the same direction than when they face one another.[⤒]