Leaving Hollywoo: Essays After BoJack Horseman

In Season 2 of BoJack Horseman, Hollywoo agent Princess Carolyn learns that J. D. Salinger is alive, hiding out at Joe Nobody's Shop for Tandem Bicycles, having faked his own death to avoid constant attention from admirers of The Catcher in the Rye. "Every time I go out into the world," he says, "people hound me about my books . . . well, book." Princess Carolyn's rejoinder:

What if I told you there was a place where no one reads books? A place where people only read headlines, lists, and pictures. A place where people hate reading so much, they hire others to do it for them — and don't even pay a living wage!

"Does such a place truly exist?" Salinger asks in wonderment. Princess Carolyn answers, "Come with me, J. D. Salinger. Let's go to Hollywoo." Soon "J. D."1 is the showrunner of the new Mr. Peanutbutter vehicle, a cockamamie quiz show with an ungainly title and few discernible rules: Hollywoo Stars and Celebrities: What Do They Know? Do They Know Things? Let's Find Out!

We could be forgiven for thinking that this version of Salinger bears a merely cartoonish relation to the real author of what Princess Carolyn gamely calls "The Catcher in the Rye . . . and . . . others . . . ?" To be sure, reanimating the famously fastidious writer and having him embrace the trivia gameshow medium is a classic moment of BoJack bathos. J. D.'s demands that someone fetch him a "bananafish sandwich," his desire to be represented by an agency "at least nine stories" tall, or his brandishing of the four-color ballpoint pen through which he "bled Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters upon the page," might all bespeak a certain throwaway iconoclasm in the show's approach to its august guest star. But Salinger's cameo also sheds light on one of BoJack's most persistent themes, which is finally one of its ethical and aesthetic keystones: that an artist needs to relinquish some control of their work in order to achieve art's ultimate purpose, authentic connection with an audience.

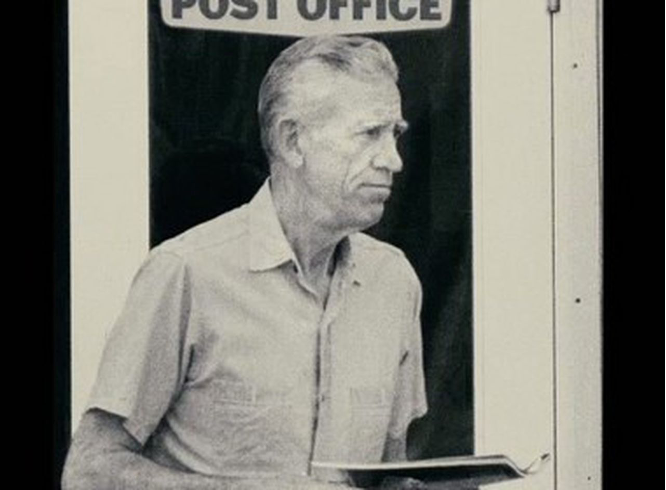

The real J. D. Salinger (d. 2010) demonstrated deep skepticism about the entertainment industry. In 1949, when his short story "Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut" was adapted by Philip and Julius Epstein (co-writers of Casablanca) into the movie My Foolish Heart, he supposedly spent an entire evening "spouting off about Hollywood. I think he had just seen My Foolish Heart and was fit to be tied."2 Elsewhere Salinger claimed not to have even bothered to see the film of his story, having only heard that the Epstein brothers had "loused it up nicely."3 He refused multiple overtures by filmmakers to adapt Catcher for the screen; in the novel itself, Holden Caulfield slams his brother D. B. as a "prostitute" for having moved to Hollywood to work as a screenwriter, and opines that the "goddamn movies . . . can ruin you, I'm not kidding."4 Salinger's other stories — especially those about the former child star siblings Seymour and Buddy, Franny and Zooey Glass — abound with the gloomy consequences of the "footlight and three-ring heritage" of a life in the performing arts.5 Salinger also did not think celebrity was part of an author's job; long secretive in his personal affairs, he effected a total retirement from public life after the appearance of his short story "Hapworth 16, 1924" in the New Yorker in 1965. Attempts were made over the years to solicit interviews, even write his biography; the odd long-lens photograph was sneaked or handshake extorted, but by all accounts this made Salinger angry. "Being a public writer interferes with my right to a private life," he said. "I write for myself."6

BoJack Horseman's relationship with his public is more ambivalent. When we first meet him, he has spent twenty years coasting on the residuals from Horsin' Around, obsessively watching old episodes and longing to be recognized by the "not-famouses" for his role in the show. He sees his autobiography, to be ghostwritten by Diane Nguyen, as his "last chance to make people love me again,"7 but loses control of the resultant book, a tell-all biography in which, according to BoJack, he "comes off like a total asshole." In fact, as Diane points out, he "comes off as complex and deeply troubled but ultimately sympathetic . . . This will actually do wonders for your career, trust me."8 Diane is right: audiences do respond to this new relatable BoJack, far from being put off by his flaws instead; and studios follow suit by offering him more serious roles, though these bring fresh troubles. In Season 5, BoJack stars in the gritty HBO-style procedural Philbert and in the course of filming becomes addicted to painkillers, increasingly unable to tell the difference between himself and the troubled detective he is playing. Philbert is a hit with audiences and critics, but ultimately Diane (who has worked as a character consultant on the script) is disgusted by its success, fearing that, with its vulnerable, flawed anti-hero, the show might just provide "a way for dumb assholes to rationalize their own awful behavior."9 As Michael Docherty notes in his discussion of Emily Nussbaum's idea of "bad fandom,"10 this is a hot button for a series like BoJack, self-conscious heir to the "Difficult Men" school of television arguably incepted by The Sopranos and refined by Mad Men, both shows whose success depended in heavy part upon the audience's sympathy and identification with destructive, sociopathic protagonists.11

The real Salinger certainly had some "bad fans" — the "phony"-allergic hero of his most famous novel supposedly inspired more than one murderous assassin in the 1980s — but his withdrawal from publication predated those horrors by many years, and appears to have had more to do with a generalized mistrust of the interdependence involved in the author-reader relationship. This is what BoJack co-creator Raphael Bob-Waksberg, discussing fans' alternative interpretations of the ending of the show, has called "the equation of art. As soon as it goes out into the world, it belongs to the world, right? . . . I did as much as I could by making the show itself, and the rest of it, that's your part of the work."12 That is not far from Salinger's careful statement, to a fan who, seeing him as a kindred spirit, had travelled to meet him, that "I, perhaps, pose questions about life in my stories, but I don't pretend to know the answers."13 The crucial difference is that Salinger concluded it was safest not even to pose those questions any more, denying his devoted readers access to the stories he continued writing for the rest of his life but refused to publish. For The New Yorker's Louis Menand, Salinger's retreat from publication was the consequence of a self insufficiently robust to withstand the greater reality of the fiction he had created (like BoJack dissolving into Philbert?): his real "presence began to dissolve into the world of his creation. He let the puppets take over the theater."14 That formulation supposes the puppets in question were only Salinger's characters, but this is perhaps to fall too straight-facedly for the author's own self-mythology; we have every right to be as irritated as we are charmed by his cute insistence, for instance, that the reason he published so little was because "my alter ego and collaborator, Buddy Glass, is insufferably slow."15

According to John Wain, Salinger exploits his audience's goodwill even with the Glass family stories he did deign to publish: "Mr. Salinger ought to consider us a little," he mourns, reporting "the temptation to an ungenerous ribaldry" in his analysis of Franny and Zooey's "page upon page of essay-material, uneasily broken up by cigarette-lighting." The Salinger critic, Wain notes, no matter how touched by his soulful characters, experiences a strong "temptation to just let go and horse around,"16 given the strong likelihood that our author has just been horsing around with us.

This thought returns us to BoJack Season 2, Episode 8, "Let's Find Out," in which BoJack is a guest on the very first instalment of Hollywoo Stars and Celebrities — although he is only the "little celebrity"; Harry Potter's Daniel Radcliffe is the big one. The more ridiculous the show becomes, the more the studio audience seems to enjoy it and applaud — leading J. D., up in the control room, to observe over a sinister musical cue: "The puppets clap when the puppet-master pulls the strings." The drama ramps up when it comes out that Mr. Peanutbutter knows something that BoJack's audience witnessed a full season ago: BoJack made a pass at Diane. As Mr. Peanutbutter and BoJack prepare to talk it out, J. D. gives directions for the rain machine to be switched on over them — "Now this is television!" he crows, "Turn on the rain!" A soulful on-air back-and-forth is the result, in which BoJack makes an apparently genuine apology, confessing that his resentment of Mr. Peanutbutter comes down to jealousy over the cheerful dog's ability to feel good about himself, while BoJack is mired in self-hatred. "I don't know if I can forgive you," says Mr. Peanutbutter, sadly and thoughtfully, "but I guess we'll find out . . . right after this break!" Reminded backstage that "this is network television, so resolving everything cleanly in a half-hour is kind of what we do," Mr. Peanutbutter duly decides he will forgive BoJack live in the studio. The crowd goes wild. Upstairs, his race run, Salinger sighs, "Oh, if only I'd had a kiss cam for Catcher in the Rye. Well — just one more regret on a long list of many."

We do not need to wish a kiss cam on The Catcher in the Rye to agree with J. D. that something extraordinary has taken place amid the apparent chaos of "Let's Find Out." BoJack is telling the truth when he admits his insecurities to Mr. Peanutbutter, but having apologized, he does not know if he is truly forgiven; nor does Mr. Peanutbutter know if he would have chosen to pardon BoJack of his own accord: they have both been had, and so has the studio audience, who thrilled to the whole confected circus act. If the mockery of network television is standard BoJack fare, then there is also a particularly Salingerian cruelty and poignancy to this episode. J. D. is as scornful of, and reliant on, his television audience as the real Salinger was of his readers. But BoJack calls attention to the selfishness of that approach by putting the cartoon J. D. in a situation where it is not fictional characters, but real people, he is moving around like chess pieces (or puppets), and all only in order to provoke a response in some other people (or puppets) he holds in contempt — whom he'll then forsake, a few episodes later, claiming, "I told the story I wanted to tell. To prolong it for commercial reasons would be crass and inorganic." J. D.'s exertion of Svengali-like control over his characters and audience alike, and the pious volte-face by which he finally rejects them all, constitute BoJack's satirical denunciation of the real Salinger's punitive attitude towards a readership who, unlike his obedient characters, refused to stay where he put them.

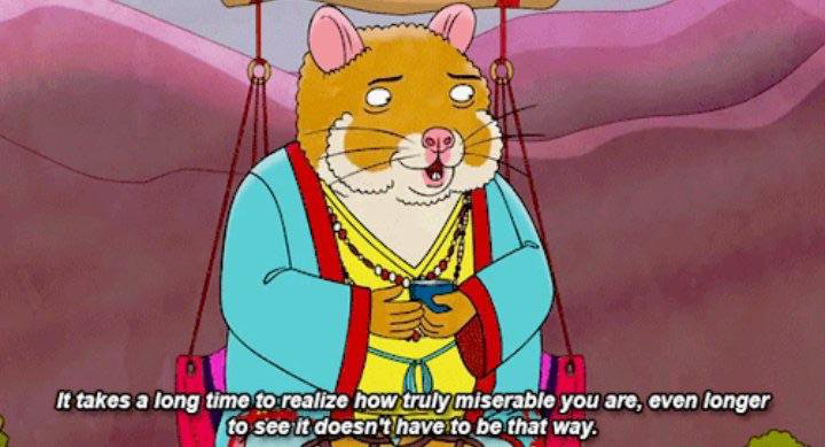

This disavowal is confirmed by the episode immediately after J. D.'s surprise resignation from Hollywoo Stars and Celebrities and his retreat, we guess, back into upstate anonymity,17 when we are introduced to a personage who is probably the closest analogue in the BoJack universe to the real J. D. Salinger: the hamster Cuddlywhiskers. Reclusive, renunciatory, somewhat nonspecifically spiritual,18 Cuddlywhiskers first appears in a flashback set in 2007, in which we learn that BoJack is haunted by the failure of another prestige television show in which he might have starred: The BoJack Horseman Show. By the time we meet Cuddlywhiskers in the present day, he has renounced Hollywoo for a quiet life running a rehabilitation center in Ojai, with a ranch house and a hammock, meditating on the belief that "only after you give up everything can you find a way to be happy."19 In his words we can hear the voice of Salinger's Zooey Glass, advocating for "detachment, buddy, and only detachment. Desirelessness. 'Cessation from all hankerings.'"20 Back in 2007, though, Cuddlywhiskers is fresh out of rehab himself, confessing that seven years on the hit show Krill & Grace have not fulfilled him, and that he is now "trying to do something different . . . something that lasts." That something is The BoJack Horseman Show, by the sounds of it a proto-Philbert, a dramatic series that will showcase BoJack's serious acting chops. Frightened the new show won't succeed, but even more frightened that it will (one executive predicts it will be "as big as Horsin' Around!"), BoJack convinces Cuddlywhiskers, while drinking heavily, to undertake massive rewrites on the grounds that "the network loved [the pilot]; obviously we're playing it too safe."21 The result is a wreck; Cuddlywhiskers's writing career is ruined. When we catch up to him in the present day, however, he is over his Hollywoo disappointment. Castigated by Diane that "you can't just disappear. You really hurt a lot of people," Cuddlywhiskers's warm but firm reply is: "Sometimes you have to take responsibility for your own happiness."

This scene is complicated by the fact that, at this moment in the series, both BoJack and Diane have recently tried disappearing on their loved ones. Neither succeeded in building a new life elsewhere; both returned to Hollywoo, old habits, and dissatisfaction. Taking Cuddlywhiskers to task for his life of detachment, Diane is actually angry with herself and with BoJack, too — though whether for running away, or for running away from running away, we cannot totally tell. It is a long time after the encounter with Cuddlywhiskers before either BoJack or Diane learns to "take responsibility for their own happiness"; and although both will step away from Hollywoo in order to do so, neither of them stops trying to reach out to people through their work (even if BoJack temporarily has to direct plays not at Wesleyan, but in prison). It is only at the end of Season 6, after all, that Diane accepts that the book she really wants to write is the young adult novel Ivy Tran, Food Court Detective. It's not her New Yorker dream, but writing it makes her happy and brings her professional success.

If BoJack offers any overarching theory of how to balance personal happiness with artistic achievement it surely lies in the importance of striving for connection — with the people in your life, with an audience — even if that means compromise, even if it comes with the risk of being mis- or insufficiently understood. Bob-Waksberg is clear that this does not mean abdicating responsibility; he has said so:

This show is touching people and moving people and causing them to think about stuff, and so we have to take that seriously and think about what kind of messages we're putting out there and how they're being interpreted . . . But . . . it's your job to take whatever you take from it. I can only hold your hand so far, in a way.22

As the above quotation makes clear, Bob-Waksberg's very un-Salingerian sanguinity about holding and then letting go of his audience's hand is linked to his conviction that BoJack is successful at connecting with its audience, "touching people and moving people." Diegetically, this is one of the show's tenets, as unpacked by Caroline Hovanec in her dissection of "Fish Out of Water," whose "tagline," she notes, "might as well be . . . 'only connect'."23 The pursuit, if not always the total attainment, of personal connection certainly animates BoJack, who in the same episode states in his apology letter to Kelsey, which dissolves before she can read it, that "In this terrifying world, all we have are the connections we make."24 And it clearly animates BoJack, too, which, as Bob-Waksberg says, may not have been "a show that set the world on fire . . . but it's a show that's connected with people."25 One is finally reminded of the persistent rumors that BoJack ended in 2020 after six seasons not because Raphael Bob-Waksberg and Lisa Hanawalt had, like J. D., "told the story they wanted to tell," but because Netflix cancelled the show. Perhaps the audience would have received the final episodes in just as tragic and reverent a spirit, either way. A meme went around among fans at the time: a screengrab of Tony Soprano in therapy, defensively remarking over Dr. Melfi's insistence on analyzing his grief at the loss of his much-loved thoroughbred Pie-o-my: "Can't I just be sad for a horse?"

The joke is distributed evenly between BoJack's naysayers and its devotees, brought to feel "sad for a horse" as, in the first golden age of TV, audiences were brought to feel sad for emotionally incontinent mob bosses and promiscuous ad men. BoJack belongs to a newer generation of prestige television, which riffs on its forebears but has also found new ways to resonate with its audience in a world ever more atomized and uncertain. There are a lot of laughs too, but viewers of BoJack Horseman do indeed find ourselves in the unusual position of feeling "sad for a horse" — a cartoon showbusiness horse at that — and sad for all his cartoon friends, an effect worked on us by the show's combination of visual gags, exquisite puns, and searing depictions of addiction, depression, and anomie. It may not be what J. D. Salinger had in mind but, these days, that's television. Turn on the rain!

Roberta Klimt (@robertaklimt) is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the Department of English at King's College London, working on John Milton and the Italian questione della lingua. She teaches and researches seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English literature, along with medieval and Renaissance Italian; and also writes on Jewish-American fiction, especially Philip Roth.

References

- Note: in order to distinguish between BoJack's Salinger and the real-world author, for the remainder of this essay I will refer to the former as J. D., as he is known in the show, and the latter as Salinger.[⤒]

- Testimony of Jean Miller, quoted in Dave Shields and Shane Salerno, Salinger (London: Simon and Schuster, 2013), 208.[⤒]

- J. D. Salinger to Paul Fitzgerald, 26 August 1946, quoted in Salinger, p. 208.[⤒]

- Salinger, The Catcher in the Rye (1951, this edition, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1994), 1, 94.[⤒]

- "Seymour: An Introduction" (1959), in Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters & Seymour, An Introduction (1963; this edition New York: Bantam 1965), 146.[⤒]

- Michael Clarkson's recollection of a conversation with Salinger in 1979. Salinger, 101.[⤒]

- BoJack Horseman. "Downer Ending." Directed by Amy Winfrey. Written by Raphael Bob-Waksberg, Kate Purdy. Netflix, August 22, 2014.[⤒]

- BoJack Horseman. "One Trick Pony." Directed by JC Gonzalez. Written by Raphael Bob-Waksberg, Laura Gutin. Netflix, August 22, 2014.[⤒]

- BoJack Horseman. "Head in the Clouds." Directed by Amy Winfrey. Written by Raphael Bob-Waksberg, Peter A Knight. Netflix, September 14, 2018.[⤒]

- Michael Docherty, "Good Boy Gone Bad: The Rot in Mr. Peanutbutter's House," Post45, November 23, 2020.[⤒]

- See Brett Martin's Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution (2013), which connects these shows' antiheroes with their often problematic auteurs.[⤒]

- Liz Shannon Miller, "'BoJack Horseman' Creator on Legacy, That Ending & What He Thinks About the Future of Animation," Collider, August 25, 2020. [⤒]

- Salinger, p. 98.[⤒]

- Louis Menand, "Holden at Fifty," New Yorker, October 1, 2001.[⤒]

- This was printed on the dust jacket of Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction (1963).[⤒]

- John Wain, "Go Home, Buddy Glass," The New Republic, January 1, 1970 (first pub. 1963). [⤒]

- For completeness, I should mention that J. D. makes brief background appearances at two parties thrown by Mr. Peanutbutter, in season 5's "The Dog Days are Over" and season 6's "Surprise!".[⤒]

- Half-Jewish, half-Christian, Salinger appears at different times in his life to have subscribed to several religions but was especially interested in Zen Buddhism and in Vedanta, a branch of Hindu philosophy.[⤒]

- BoJack Horseman. "BoJack Kills." Directed by Amy Winfrey. Written by Raphael Bob-Waksberg, Kelly Galuska. Netflix, July 22, 2016.[⤒]

- J. D. Salinger, "Zooey" (1957), Franny and Zooey (1961; this edition New York: Bantam, 1964, repr. 1981), 198.[⤒]

- BoJack Horseman. "The BoJack Horseman Show." Directed by Adam Parton. Written by Raphael Bob-Waksberg, Vera Santamaria. Netflix, July 22, 2016.[⤒]

- Collider interview.[⤒]

- Caroline Hovanec, "Only Connecting in Pacific Ocean City," Post45, November 23, 2020.[⤒]

- BoJack Horseman. "Fish Out of Water." Directed by Mike Hollingsworth. Written by Elijah Aron, Raphael Bob-Waksberg. Netflix, 22 July 2016.[⤒]

- Sarah McCammon, "'BoJack Horseman' Rides Into The Sunset," NPR, February 1, 2020. [⤒]