Leaving Hollywoo: Essays After BoJack Horseman

For the past few years, I've been teaching the BoJack Horseman episode "Fish Out of Water" in my writing courses. The episode forgoes dialogue for about 23 of its 26 minutes, as BoJack ventures to Pacific Ocean City for an underwater film festival. It is perhaps the most critically acclaimed episode of the series, and it also happens to be my favorite — I find it sad, funny, hopeful, even beautiful.

I don't talk much about that attachment when I teach the episode, though. Instead, I frame it as a tribute to old movies — silent cinema and early works of the sound era, films that used music and non-vocal sound but not speech. I play my students Steamboat Willie (the first released Mickey Mouse film), Merbabies (the Disney short whose under-the-sea parade delighted Sergei Eisenstein), and the iconic factory scene from Modern Times (in which Charlie Chaplin's Little Tramp is pulled down a fast-moving assembly line into the gears and levers of a giant machine).1

Part of what I'm doing is trying to persuade my students that the cultural past is still alive, still relevant, and worth learning about. In imitating the moving pictures of an earlier era, "Fish Out of Water" participates in the trend of pop nostalgia. Like Stranger Things mining and miming the 1980s, or Mad Men with the 60s, or even other BoJack episodes with the 90s, "Fish Out of Water" can be read as the series' take on cinema in the golden age of the 1920s and 30s.

It's possible to read the contemporary propensity for pastiche, though, as a sign not that the past is still alive, but that there's something dead about the present. Some critics have diagnosed this persistent cultural nostalgia as decadent, even pathological. Fredric Jameson's well-known essay on postmodernism describes pastiche as an indicator of cultural lifelessness: "in a world in which stylistic innovation is no longer possible, all that is left is to imitate dead styles, to speak through the masks and with the voices of the styles in the imaginary museum."2 Mark Fisher, drawing on Jameson, describes nostalgia as a symptom of a twenty-first-century culture that is politically deadened and creatively exhausted. When we can no longer imagine a good future, he suggests, we take comfort in revisiting the old forms over and over ad nauseam.3

The result (if we follow Fisher) is a contemporary mode of aesthetic experience marked by "anachronism and inertia." Because our moment lacks coherence, our art is merely a "montaging of earlier eras."4 When I teach "Fish Out of Water" as a medley of allusions to old films, I might be said to be confirming this cultural logic. What the episode might amount to, in that reading, is a monument to a lost past, a postmodern jumble of fragments that speak only of their own disconnection.

But what if we read "Fish Out of Water" on its own terms? I think its return to aesthetic styles from the 1920s and 30s would then appear as an instance of metamodernism directly in keeping with its thematic longing for something like communion. Metamodernism is, in David James and Urmila Seshagiri's account, a tendency within contemporary literature to engage with the forms and commitments of the early twentieth century; in Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker's formulation, it's a negotiation between "a typically modern commitment and a markedly postmodern detachment."5 "Fish Out of Water," as steeped in ironic humor as any BoJack episode, is also committed to a relational ethics and aesthetics. Its plot is about BoJack's need to forge authentic relations with others, and its allusive style points to the show's need to establish relations with other works of art. Its tagline might as well be (to borrow a modernist mantra from E. M. Forster) "only connect."

***

"Fish Out of Water" features a lonely and alienated BoJack, visiting Pacific Ocean City to promote his new movie Secretariat at an underwater film festival. Isolated within a clear bubble helmet that disallows his usual vices (smoking, drinking, talking shit), BoJack spends most of the trip trying to reunite a lost baby seahorse with his father. In the episode's B plot, BoJack tries to reconcile with the director Kelsey Jannings, whom he had gotten fired from Secretariat in an earlier episode.

One needn't go all the way back to the 1920s and 30s to find the episode's antecedents. Perhaps its most direct influence is Sofia Coppola's 2003 film Lost in Translation. The two white protagonists of that film, played by Scarlett Johansson and Bill Murray, experience isolation and culture shock as English-speaking Americans in Japan. This shared isolation leads them to forge a meaningful if temporary connection with each other. "Fish Out of Water" borrows a number of things from Lost in Translation: not only a focus on loneliness and friendship, but also an exoticizing, Orientalist portrayal of (something like) Tokyo. For example, both works make jokes based on the stereotypical "wacky" Japanese-style commercials featuring American actors (here, Mr. Peanutbutter stars in a commercial for Seaborn baby formula). "Fish Out of Water" is slightly more knowing about its Orientalism than Lost in Translation is — the cold open is frank about BoJack's racism, as he complains to his agent about how fish are "so annoying" and rudely tells a fish seated next to him, "No habla fish-talk" — and I don't think the episode mocks or belittles the inhabitants of Pacific Ocean City as Lost in Translation does for Tokyo. But, it must be acknowledged, the plot still turns on the alienation of a white-coded, American character in a strange, incomprehensible Eastern setting.67

As my students usually point out, and as Emma Mason beautifully explores in her contribution to this cluster, the episode is about BoJack's attempts to overcome this alienation and make connections with others. BoJack comes to recognize his ethical obligations when he finds himself, despite his initial reluctance, beguiled by an adorable, lost baby seahorse. BoJack takes the baby seahorse under his wing and eventually reunites him with his family, a moment that becomes bittersweet when BoJack must say goodbye to his new friend. After this cute but transient bonding experience, BoJack is finally able (after several earlier abortive attempts) to write an honest apology note to Kelsey. It reads, "In this terrifying world, all we have are the connections that we make. I'm sorry I got you fired. I'm sorry I never called you after":

The note, unfortunately, becomes smudged and illegible before Kelsey gets the chance to read it; as Mason observes, it is "a moment in which it feels that attempts at connection, communication, and affection will always be derailed."8 I think the failure is important, but it doesn't negate the note's insight so much as coexist with it. It's the oscillation between the two — connection and failure — that makes the episode's story poignant.

The word my students use for this poignancy is "relatable." Indeed, much of the critical discourse on BoJack Horseman focuses on the show's relatability. It just gets depression, loneliness, addiction, failure, and shame on a visceral level, fans say. For scholars, though, there's something embarrassing about the very notion of relatability. It's a critical judgement that fails to be critical enough, a gooey, self-centered appraisal.9 I think that vague embarrassment about the "relatable" is why, in my teaching, I usually say little of my own attachments to the episode and instead foreground its formal features and parallels to early film. It feels smarter to talk about form and style rather than plot, and more empirical to talk about film history than feelings.

But Brian Glavey has recently recuperated relatability, reframing it as a way of talking about "the relationality and sociability of art."10 To label an artwork (in Glavey's example, a Frank O'Hara poem) "relatable" may seem to be about expressing an intense individual identification with a character or speaker, based on traits or experiences held in common. But how, then, could an O'Hara poem be relatable to a reader who has never been to the museums O'Hara writes about, who has never seen the artworks he mentions, who has not been through the hyperspecific experiences described in O'Hara's work? In Glavey's view, this relatability is not really about seeing oneself in a poem; rather, it's about using aesthetic judgment as a way to connect with others. "Relating to certain authors and not to others becomes a way of relating to your friends," he says. "Such judgments create a social world and put art in contact with it."11 When a student says that "Fish Out of Water" is relatable, then, they are trying to connect not only with BoJack, but also with their classmates and with me. And they may also be reflecting the episode's own concern with relationships (as Glavey's students mirror O'Hara's interest in the relationships that make, and are made by, art).

As my students correctly note, BoJack's relationships with the baby seahorse and with Kelsey Jannings anchor the episode's plotline. What I want to teach them is that there are other relationships central to the episode and its apparent relatability: that of the viewer to the work of art, and of one work of art to others.

***

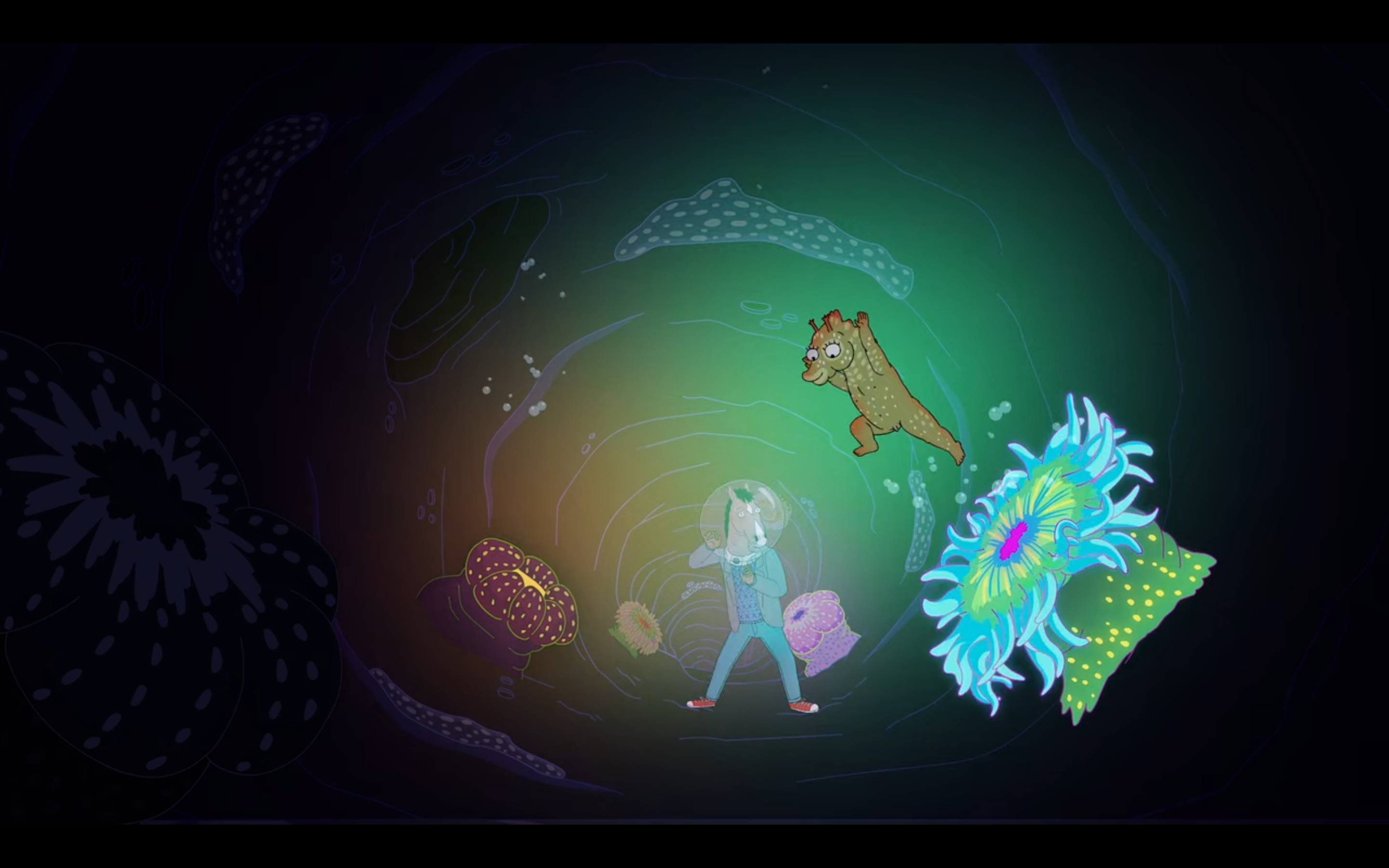

To show my students how "Fish Out of Water" is related to earlier films, I usually focus on the sequence at the center of the episode. On the run from a bat-wielding shark named Tim Jaws, BoJack and the seahorse baby tumble down an underwater cliff to a dark valley. It is, they soon discover, a magical den of sea anemones, corals, and other strange marine creatures. The anemones light up and play musical notes when touched. The baby seahorse makes a game of leaping from one to another, creating a song and dance of lights, while the larger, clumsier BoJack attempts to keep up:

I replay this scene for students alongside Steamboat Willie. Made in 1928, Steamboat Willie was Walt Disney's first sound film, but it, like "Fish Out of Water," has no dialogue, only noise and music. The music is closely tied to the animation, as Mickey and Minnie Mouse "play" the other animals around them in a symphony: turning a dog's tail like the wind-up mechanism on a music box, making a xylophone of a cow's teeth. It's this sort of doubling — a spoon can be a drumstick, a duck can be a bagpipe — that led Eisenstein to rave about Disney films. To him, they represented a "transformed world, a world going out of itself."12 Steamboat Willie, I tell my students, is probably the first instance of the Mickey-Mousing technique (synchronizing music with characters' actions). And in "Fish Out of Water," too, the characters make music from other animals, accompanied by an electronic beat by Jesse Novak.

The chase eventually leads BoJack and the baby seahorse to a "freshwater taffy" factory (the very factory where the seahorse father works). The baby seahorse begins to dance nimbly around the factory floor, oblivious to danger, while BoJack crashes into things, mashes buttons, and punches workers in a frantic attempt to stop the assembly line so that the baby won't get pressed into taffy. At the climactic moment, BoJack leaps gracefully through the tamping machine itself, scooping the baby up and out of danger just in time. Taffy explodes everywhere, causing angry fish security guards to pursue BoJack, this time in comically slow motion as they wade through a flood of pink taffy:

I replay this scene for my classes alongside the famous factory scene from Modern Times. Both scenes draw on the frenetic pacing of the factory floor and the threat of injury or death to create the kind of slapstick comedy that Sianne Ngai has described as zany: "a ludic yet noticeably stressful style" that is "as much about desperate laboring as playful fun."13 Chaplin's film, I explain to my students, is often read as a critique of modernization, industrialization, Taylorization, and their dehumanizing effects on people. It suggests that surviving as a worker requires both clumsy labor and virtuosic performance.

One could argue that "Fish Out of Water" echoes the critique of capitalism that Chaplin's film offers (and even updates it by making a spectacle of the labor of child care, on top of the spectacle of capitalist production). I think, though, that these allusions to old films are also meaningful in a different way. The episode's nostalgia for works of early cinema might also be a nostalgia for an idealistic culture of cinema that existed in the first few decades of the twentieth century.

There were, in film's early years, cinephiles who believed that film had special potential for democratic sociality. A pillar of this belief was the idea that silent film constituted a universal language. As Miriam Hansen explains, "the defense of film as a universal language plays upon the utopian vision of a means of communication among different people(s)." In early-twentieth-century America, silent cinema and immigrant audiences were thus considered to have a natural affinity.14 Without spoken language, early film seemed uniquely able to cross linguistic barriers to speak to any viewer. (I was reminded of this history when reading a student paper by an English language learner which observed that "Fish Out of Water" was easier to understand than other episodes because of its nonverbal storytelling.)

Animation, too, carried a special promise in the period before World War II, as Esther Leslie has shown. Theorists including Eisenstein and Walter Benjamin admired early cartoons as exemplars of a "demotic modernism," or a modernism for the people.15 For Benjamin, Mickey Mouse cartoons spoke to viewers because they were intensely relatable: "the public recognizes their own lives in them."16 As Leslie explains, "Disney's cartoon world is a world of impoverished experience, sadism, and violence. That is to say, it is our world."17 For Eisenstein, on the other hand, Disney cartoons offered viewers trapped in dull, mechanical lives a "drop of comfort." The films' bright colors, plasmatic forms, and refusal of ordinary physics had a therapeutic effect on viewers, he believed.18

None of these idealistic beliefs about cinema is unproblematic. As Hansen cautions, the idea of silent cinema as a universal language "foreshadows the subsumption of all diversity in the standardized idiom of the culture industry, monopolistically distributed from above."19 The culture industry also domesticated cartoons, according to Leslie; the anarchic pleasures of Steamboat Willie were quickly replaced by the "priggish morality" and middlebrow respectability of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.20 Even as Benjamin and Eisenstein were writing in praise of Disney, they were already in a nostalgic mode for a potentiality that they knew was being lost.

BoJack Horseman mostly operates in the realm of bourgeois realism and psychological depth that Leslie's modernist theorists saw as a fall from animation's early achievements. But "Fish Out of Water" might be seen as a reminder of that other possibility. The unruly factory chase, the taffy explosion, the escape from and laughter at the boss and security guards — all are hints of what the cartoon might have been. Or, indeed, of what it still might be, if we linger long enough on its candy-colored surface. In the animistic story world, in the madcap sounds of Princess Carolyn's tongue-twisters, in the chaotic subplots of Todd and Mr. Peanutbutter, in the formal experimentation of episodes like "Free Churro," "The Old Sugarman Place," and of course "Fish Out of Water," and throughout the series, we might still see traces of a demotic modernism.21

***

Failure, aesthetic and otherwise, is a recurrent theme in BoJack Horseman and in the theoretical works I've cited above. Teaching "Fish Out of Water" has been, for me, a failure of connection too in some ways. I have to confess now that my students are usually a lot less enthusiastic about the episode than I am. Without the fast-paced, screwball dialogue that is otherwise a fixture of the series, "Fish Out of Water" is boring and slow, they say. Or it's too depressing — after all, BoJack leaves Pacific Ocean City forgotten by the baby seahorse and unforgiven by Kelsey Jannings. (I was shocked the first time a student told me this — I thought I had chosen an uplifting episode!) Sometimes students like the series — they find BoJack's and Diane's struggles with mental health relatable, and Todd's zany antics are usually a hit — but this episode falls flat.

Or at least it does in class discussion. In student writing, though, it's a different story. I've read beautiful essays about culture shock, nostalgia, depression, animation history, silence that take "Fish Out of Water" as a primary text. What feels like a failure of connection in the moment often ripens, over time, into something else.

I suppose that's one of the reasons why I find "Fish Out of Water" so relatable. In the classroom, sometimes my painstakingly thought-out communiques turn out to be illegible. Relationships with students are usually short-lived, and the connection that happens when two or more people love the same thing is usually belated, if it happens at all. Pedagogy is, I increasingly think, an art of relations, but it's one littered with as many flops and false starts as BoJack's own life. And still, it's animated by a persistent hope that this time, the connection will happen, and this time, it will be magic.

Caroline Hovanec (@CariHovanec) teaches English and Writing at the University of Tampa. She is the author of Animal Subjects: Literature, Zoology, and British Modernism (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

References

- Sergei Eisenstein, On Disney, translated by Alan Upchurch, edited by Jay Leyda (Seagull, 2017), 20-26.[⤒]

- Fredric Jameson, "Postmodernism and Consumer Society," in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Hal Foster (Bay Press, 1983), 111-125, quote on 115.[⤒]

- Mark Fisher, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures (Zero Books, 2014), 8.[⤒]

- Ibid., 6.[⤒]

- David James and Urmila Seshagiri, "Metamodernism: Narratives of Continuity and Revolution," PMLA 129, no. 1 (2014): 87-100; Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker, "Notes on Metamodernism," Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 2, no. 1 (2010).[⤒]

- We might find this centering of a white(ish) male experience all the more disturbing in light of Ben Carver's argument that BoJack's persistent problem is his "failure to acknowledge [minor characters] properly." See Ben Carver, "'Major Falls and Minor Lifts': The Character System of BoJack Horseman," Post45.[⤒]

- On Orientalist tropes in Lost in Translation, see, for example, Homay King, "Lost in Translation [review]," Film Quarterly 59, no. 1 (2005): 45-48. [⤒]

- Emma Mason, "'How Do You Not Be Sad?': Sadness and Connection in BoJack Horseman," Post45.[⤒]

- See, for example, Rebecca Mead, "The Scourge of 'Relatability,'" The New Yorker, August 1, 2014.[⤒]

- Brian Glavey, "Having a Coke With You is Even More Fun Than Ideology Critique," PMLA 134, no. 5 (2019): 996-1011, quote on 998.[⤒]

- Ibid.[⤒]

- Eisenstein, On Disney, 26.[⤒]

- Sianne Ngai, Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (Harvard University Press, 2012), 8, 23.[⤒]

- Miriam Hansen, Babel and Babylon: Spectatorship in American Silent Film (Harvard University Press, 1991), 77.[⤒]

- Esther Leslie, Hollywood Flatlands: Animation, Critical Theory and the Avant-Garde (Verso, 2002), v-vi.[⤒]

- Walter Benjamin, "Zu Micky-Maus," in Gesammelte Schriften, edited by Rolf Tiedemann and Hermann Schweppenhäuser (Suhrkamp Verlag, 1972-91), vol. VI, 144, qtd. in Leslie, Hollywood Flatlands, 83.[⤒]

- Leslie, Hollywood Flatlands, 83.[⤒]

- Eisenstein, On Disney, 15 and passim.; Leslie, Hollywood Flatlands, 231.[⤒]

- Hansen, Babel and Babylon, 76.[⤒]

- Leslie, Hollywood Flatlands, 122.[⤒]

- Thanks to Pamela Thurschwell for pointing out to me that Princess Carolyn's tongue-twisters could be seen as inheritors of, for instance, Gertrude Stein's linguistic playfulness. And thanks to Elizabeth Alsop, Sean O'Sullivan, and all the participants in the "TV's Modernist Turn" seminar at the 2018 Modernist Studies Association Conference, who prompted me to begin thinking about modernism and television form in the first place.[⤒]