Legacies — 9/11 and the War On Terror at Twenty

At the Southern Baptist seminary where I attended college at the turn of the millennium, chapel was held three days a week. We gathered at 10am on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays to hear sermons and testimonies from pastors, evangelists, missionaries, professors, and other luminaries from across our convention of churches and beyond. In the evangelical world of the American South, culture war isn't fought on distant courthouse steps or in the halls of Congress but in the hearts and minds of every American. So, when I rushed from the computer lab to chapel on a sunny September morning in 2001 having just heard that the nation was under some kind of attack, I was only a little shocked when our school's president prayed that God would help Americans to "understand that the course of action that has been ours over the last twenty-five years is disastrous and that it courts this kind of thing."1 I was accustomed to the idea that America had been divinely appointed to make God's providence manifest to a watching world and thus also to the notion that any dereliction could be potentially disastrous to the true meaning and purpose of that mission.

From the westward expansion of the territorial United States in the nineteenth century to the spread of democracy in the twenty-first, the imperialist missions of the U.S. have historically been grounded in an ethic that positions a good us against an evil other. "Thus," observes Talal Asad, "a number of historians have noted the tendency of spokespersons of the American nation, a tendency that has dramatically resurfaced since the September 11 tragedy, to define it as 'good' in opposition to its 'evil' enemies at home and abroad." This ethic has religious entanglements that cannot be neatly separated from its nationalist goals. Asad cites as evidence Eric Foner's claim that "the country's religious roots and its continuing high level of religious faith make Americans more likely to see enemies not just as opponents but as evil."2 And so, while I was not especially stunned by the comments made in chapel that morning, many Americans were deeply offended when similar remarks were made on a more public platform by one of the most influential voices in American Christianity just two days later.

On Pat Robertson's 700 Club, Reverend Jerry Falwell stayed true to the good us versus evil other ethic by referring to the hijackers and those backing them as "Middle Eastern monsters," implicating the entire region in the acts of terrorism. But then, in a move similar to the one made by my school's president in chapel, Falwell pointed an accusatory finger at the U.S. and argued that God may very well have given us what we deserve:

What we saw on Tuesday, as terrible as it is, could be minuscule, if, in fact . . . God continues to lift the curtain and allow the enemies of America to give us probably what we deserve. [ . . . ] The ACLU's got to take a lot of blame for this. [ . . . ] I really believe that the pagans, and the abortionists, and the feminists, and the gays and the lesbians who are actively trying to make that an alternative lifestyle, the ACLU, People for the American Way, all of them who have tried to secularize America. I point the finger in their face and say, "you helped this happen."3

The White House cringed, and President Bush distanced himself from Falwell's claims.4 No doubt many Americans and many American Christians were upset by what Falwell said as well, and the culture warrior apologized soon after.5 Some progressive religious leaders also claimed that the U.S. had reaped what it sowed on 9/11, though for fundamentally different reasons. Perhaps most famously, Reverend Jeremiah Wright referred to the attacks as the chickens of American foreign policy coming home to roost.6 However, where Wright's critique acknowledges the corruption of the us, Falwell's condemnation of America somehow retains the good us versus evil other ethic that has been as central to the War on Terror as it was to Manifest Destiny and American expansionism. Why would conservatives like Falwell disclaim the purity of America's goodness as the nation grieved? Does this condemnation diminish the explanatory power of the evil other in the logic of American imperialism?

Though this critique of America may seem antithetical to the good versus evil ethic, it is, in fact, complementary in a manner that becomes evident if we look at the War on Terror (and American imperialism more broadly) in relation to the internal struggle of culture war, especially with regard to religion. When the president of my school passed judgment on American culture, he ended his prayer by entreating God to "intervene in our behalf," to "save our country," and to "make us the great missionary nation that we ought to be."7 Notice here that the work of being a missionary is not the responsibility of Christians or the church generally, but that the nation itself is a missionary. For religious culture warriors, there is an inherent connection between purifying American culture by restoring it to its mythic Christian roots and the belief that the nation itself is divinely appointed as a missionary to other nations of the world. The problem is that, when a nation becomes a missionary, the mission inevitably becomes empire.

For America to overcome the evil other, it must first be good, and so a culture war must be fought on the home front if the nation is going to fulfill its mission abroad. And yet, culture war is not prerequisite to empire. Rather, the two are symbiotic, with culture war ensuring the purity of the imperialist project and the imperialist project serving as a purity test in the culture war. I call this dynamic culture war imperialism. At the heart of culture war imperialism in the U.S. is what sociologists Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry have defined as Christian nationalism, "an ideology that idealizes and advocates a fusion of American civic life with a particular type of Christian identity and culture."8 In the late twentieth century, a series of religio-political skirmishes converted a handful of domestic issues—race, abortion, sexuality, anti-communism, preferential treatment for Christianity—into shibboleths for Christian piety for many American evangelical Christians, conservative Catholics, and scores of social conservatives who are not especially religious. For Christian nationalists, to defeat America's enemies (especially communists), America itself had to be reconciled to its divine calling. When the communist threat subsided in the decade prior to 9/11, these culture war battles took on new significance as the internal "war for the soul of America" became an end in itself.9

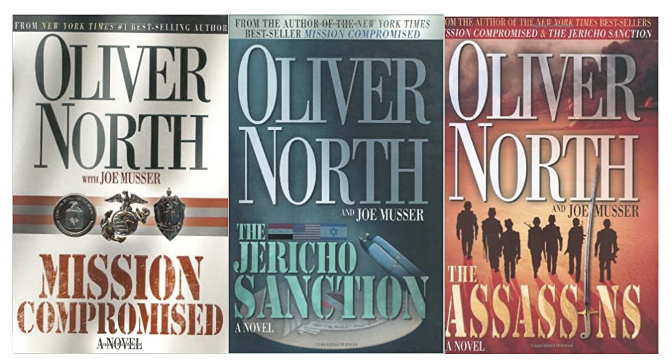

When the towers fell on 9/11, Christian nationalists like Falwell didn't simply see an evil other encroaching on the holy ground of America. They also saw a test that would reveal whether America was being true to its providential destiny. The invasion of Afghanistan, the incursion in Iraq, and the nebulous War on Terror became battlegrounds of culture war imperialism. Though much has been written about Christian nationalist responses to 9/11 and the War on Terror, scant critical attention has been paid to the small but loud burst of Christian thrillers published in the wake of the attacks. Critics have likely avoided these books for the same reasons we fail to attend to the mass market fiction of a John Grisham. But there is an added complication with overtly religious art in that it tends to be, as G. C. Waldrep conjectures, "affirming and comforting, or else it's palliative," and thus, while it lends itself to suspicious reading, it's rarely interesting for how it does the work of suspicion for us.10 Though they fall short of what Christopher Douglas calls the "hugely successful Left Behind series of Christian fundamentalist apocalyptic bestsellers," these Christian thrillers embody the culture war imperialism dynamic with plot-driven action reminiscent of the novels of Robert Ludlum or Tom Clancy.11 One series, authored by famed culture warrior and former U.S. Marine Oliver North, captures how the distinctiveness of Christian nationalism revived the good us versus evil other ethic while simultaneously using this imperialist rhetoric and the War on Terror to perpetuate the domestic culture war.

North became a Christian nationalist rockstar in the 1980s, when, as Kristin Kobes Du Mez explains, "a certain subset of Americans had been gripped by 'Olliemania.'"12 North was indicted and convicted on multiple counts for his role in the Iran-Contra affair, but was lionized by Christian nationalists for his willingness to do what he thought was necessary for the greater good of the nation, even in the face of serious consequences. He was a mainstay on the conservative Christian church and conference circuit, but the events of 9/11 revived his national reputation. In 2002, North published a novel with co-author Joe Musser. Mission Compromised became the first in a series of potboilers about Peter Newman, a Marine modeled on North himself (though "Oliver North" also appears as a character in the books). These thrillers offer more than a rationale for culture war imperialism; they envision a world in which it is essential to the idea of America (fig. 1).

North sets the first two Peter Newman novels, Mission Compromised and The Jericho Sanction (2003), prior to 9/11, and in doing so stages the War on Terror as a continuation of a battle between a good America and an evil Russia. In the mid-twentieth century, the threat of communism provided both a global enemy against which to position the U.S. as a good actor and a litmus test by which to judge who was a true American. Anti-communism, moreover, united right-wing, white supremacist political actors in common cause with evangelical Christians. Consider, for example, how labeling Martin Luther King Jr. a communist racialized communism, reified whiteness as synonymous with Americanness, and impugned the orthodoxy of King's faith. Anthea Butler notes that "while for white evangelicals personal salvation was the first order of business, during this era the second order was for born-again Americans to embrace 'Americanism' as a way to protect the nation and its citizens from the communist threat."13 A precursor to modern Christian nationalism as defined by Whitehead and Perry, "'Americanism' meant pride in the nation, in the founders, in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—and, most important, in the idea that America was a nation ordained by God to save the world."14 A product and producer of such Americanism, North wastes no time in establishing Russia as the evil enemy of the U.S. and the world in Mission Compromised and The Jericho Station.

The primary villain in these novels is former KGB officer and Soviet General Dimitri Komulakov. Komulakov devises a plot to supply Saddam Hussein's regime with weapons of mass destruction in the years prior to 9/11. North clumsily links the defunct communist empire and the terrorist crisis. Nearly every time he refers to Komulakov as a former or retired KGB agent, North puts the modifier in quotation marks, as here in The Jericho Sanction: "In the 1980s when Komulakov 'retired' from the KGB."15 By the late 1990s in North's fictional world, Komulakov has become a high-ranking official in yet another organization of which Christian nationalists are suspicious: the United Nations. When the Democratic President of the U.S. gets embarrassed on the world's stage for his military weakness, his top officials turn to the U.N. for help in developing a plan to skirt international law and eliminate some serious threats to American (and Israeli) security. Learning of a summit in Iraq that will put Hussein and Osama bin Laden in the same room, the U.S. and the U.K. work together with the U.N. to plan an assassination of these two threats. But what becomes clear is that teaming up with the U.N. in 1998 is no better than teaming up with the communists in 1988. True Americans might work with the British, but they certainly don't cooperate with the U.N. or "former" communists. Even as Newman's first major mission is compromised by America's failure to live up to its divine mandate, North imagines a world in which all the warrants for the invasion of Iraq in 2003 are realities, most notably collusion between Hussein and bin Laden and the potential presence of weapons of mass destruction.

An evil other is necessary for the Christian nationalist imagination, and so even though the Berlin Wall had been torn down and the U.S.S.R. had collapsed, Komulakov's presence in North's novels perpetuates the lingering threat of communism. 9/11 offers a way to revive this essential antagonism by creating a path of succession for evil that would lead from communism to terrorism. Du Mez argues that "In the wake of September 11, Islam replaced communism as the enemy of America and all that was good, at least in the world of conservative evangelicalism."16 Evangelical historian Thomas Kidd concurs: "for many Republicans and their evangelical allies, the 'war on terror' functioned as a substitute for anticommunism in the decades following the Soviet Union's collapse."17 This new other synthesized the ideological and racial oppositions against which Christian nationalism has defined itself. Where the F.B.I.'s attempts to connect King with communism cast suspicion on nonwhiteness and anti-capitalism by way of mutual association, the War on Terror offered an ideological and racial other all in one. North makes the succession of Islamic terrorism to the throne of evil other clear, even as he seeks to dissolve any distinctions between terrorism and Middle Eastern nations. In Mission Compromised one of Komulakov's operatives watches an Iraqi official kill a witness to their negotiation: "This man is a lunatic! he thought. He is evil—even by my standards" (296 original emphasis). The communist threat hasn't disappeared from North's landscape, but it has been outpaced by "Islamic terrorism." The new other is, if possible, even more evil than the old, and any deviation from the mission of overcoming this evil is not only a sign of weakness but also of a lack of faith in the divine destiny of the nation.

The War on Terror is inseparable from both the history of American empire and the culture wars that have shaped Christian nationalist discourse of the last half-century. North's fiction imagines the relation between the two by suggesting that any true Christian will ultimately support America and any true American will ultimately become a Christian. When Komulakov and his Iraqi insider compromise Newman's mission, leaving him stranded in the desert, he's rescued by an Iraqi named Eli Yusef Habib. Far from being an evil other, "what made Habib different from his Muslim neighbors," the narrator explains, "was that he was a Christian."18 When Newman himself seems most in doubt, not only about his country but also about his marriage, he finally finds God and, with his wife, becomes a member of an international Christian community. The consonance between Christianity and nationalism is affirmed in the American voters' choice of a new president in North's third novel, The Assassins, set after 9/11. America has elected a true Christian president, one who opens meetings in the Situation Room with prayer and takes the steps "two at a time."19 The moral murkiness of the 1990s is long gone, banished by the culture war on terror.

The mission of American empire has been predicated on the nation's commitment to imagining itself as a beacon of light in a dark world. But this imperialist ethic has also been integral to the unceasing domestic politics of culture war. On the morning of September 11, 2001, after his prayer condemning American waywardness and calling for restoration of the divine mandate, the president of my school gripped the pulpit and said that he was sure we had all registered to vote, "but if you have not, number one, as soon as you find the Lord and are saved, the next thing you need to do is register to vote. We must do this."20 He went on to insist that he would not tell us how to vote, only that we must vote. But the logic of this command was unmistakable that morning: there is an encroaching threat of evil, and this culture war we're in dictates that we must vote for the party who opposes the kinds of behaviors that brought this great evil to our shores. To stem the tide of evil at home and around the world, culture war imperialism demands that you ask God to save your soul and then vote for people who will help purify America to save the world.

In the years since 9/11, culture war imperialism has thrived on the threat of the other. When Russell Moore—former president of the political arm of America's largest Protestant denomination—took questions at the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention in 2016, he was under pressure for having stood with other faith leaders in support of a Muslim congregation in New Jersey which believed it was being subjected to unfair land-use regulations. A messenger to the convention asked Moore, "how in the world someone within the Southern Baptist Convention can support the defending of rights for Muslims to construct mosque (sic) in the United States when these people threaten our very way of existence as Christians and Americans."21 Moore answered by defending the religious liberty of people of all faiths in the U.S., but the exchange reveals the ongoing power of culture war imperialism, the desired outcome of which is not pluralism but Christian nationalism. In stark contrast to how culture war imperialism has actually played out in the War on Terror, North's imagined future is one in which the son of the Iraqi Christian who saved Peter Newman's life dutifully decides to sell the family business and take a role "in the government of the emerging democratic nation of Iraq."22 For Christian nationalists, the plan to remove all remaining troops from Afghanistan in 2021 isn't simply a question of military strategy or partisan politics. In the calculus of culture war imperialism, withdrawal symbolizes the failure of the mission to bring light to a benighted region whose people pose a threat to the very existence of Christian America.

Matthew Mullins (@MullinsMattR) is Associate Professor of English and History of Ideas at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina and the author of Postmodernism in Pieces (Oxford 2016) and Enjoying the Bible (Baker 2021).

References

- Paige Patterson, "Chapel Service September 11, 2001," Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, video, 1:23:10, SEBTS library archives.[⤒]

- Talal Asad, Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Islam, Modernity (Stanford University Press, 2003), 7.[⤒]

- Quoted in Anthony E. Cook, "Encountering the Other: Evangelicalism and Terrorism in a Post 911 World, Journal of Law and Religion 20, no. 1 (2004-2005): 4-5.[⤒]

- Sébastien Fath, "Empire's Future Religion: The Hidden Competition between Postmillennial American Expansionism and Premillennial Evangelical Christianity," 120-129, in Evangelicals and Empire: Christian Alternatives to the Political Status Quo (Brazos, 2008), 128.[⤒]

- "Falwell Apologizes for Blaming Groups for Attacks by Terrorists," Baptist Press. [⤒]

- Rev. Jeremiah Wright, "The Day of Jerusalem's Fall," (sermon, Trinity United Church of Christ, Chicago, IL, September 16, 2001). [⤒]

- Paige Patterson, "Chapel Service September 11, 2001," Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, video, 1:23:10, SEBTS library archives.[⤒]

- Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry, Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2020), ix-x.[⤒]

- The phrase "a war for the soul of America" originally comes from Pat Buchanan and appears as the title of Andrew Hartman, A War for the Soul of America (University of Chicago Press, 2015).[⤒]

- Shane McCrae and G. C. Waldrep, "Field of Encounter: A Conversation with G. C. Waldrep," in Image 107 (Winter 2020): 60. The formulation "doing the work of suspicion for us" comes from Rita Felski, "Suspicious Minds," Poetics Today 32, no. 2 (Summer 2011): 217.[⤒]

- Christopher Douglas, If God Meant to Interfere: American Literature and the Rise of the Christian Right (Cornell University Press, 2016), 128.[⤒]

- Kristin Kobes Du Mez, Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation (Liveright, 2020), 118.[⤒]

- Anthea Butler, White Evangelical Racism: The Politics of Morality in America (University of North Carolina Press, 2021), 40.[⤒]

- Ibid., 43.[⤒]

- Oliver North and Joe Musser, The Jericho Sanction (Broadman and Holman, 2002), 10.[⤒]

- Du Mez, Jesus and John Wayne, 219.[⤒]

- Thomas Kidd, Who is an Evangelical?: The History of a Movement in Crisis (Yale University Press, 2019), 137.[⤒]

- Oliver North and Joe Musser, Mission Compromised, 379-380.[⤒]

- Oliver North and Joe Musser, The Assassins (Broadman & Holman, 2005), 78.[⤒]

- Paige Patterson, "Chapel Service September 11, 2001," Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, video, 1:23:10, SEBTS library archives.[⤒]

- The full exchange between Moore and the messenger can be found here. Or see Adele M. Banks, "Southern Baptist leader defends religious liberty for Muslims," Religion News Service, June 15, 2016.[⤒]

- North and Musser, The Assassins, 525.[⤒]