Legacies — 9/11 and the War On Terror at Twenty

9/11 literary studies are characterized by an enduring whiteness, which detrimentally flattens and skews our understandings of the attacks. 9/11 was not an affront to whiteness, and its consequences — the hyper policing and securitization of Black and Brown bodies, the War on Terror, racially-motivated legislative actions such as the PATRIOT Act and Donald Trump's "Muslim Ban," to name a few — detrimentally impact people of color in material ways that simply do not affect white people. Literary criticism that aims to microscopically interrogate and understand the attacks doesn't reflect this glaringly uneven impact. Rather, the pattern of 9/11 literary scholarship centers whiteness in a way that not only jettisons the experiences of people of color, but also follows ideologies of canon formation that historically privilege white people. This results in a flawed historical perspective that perpetuates narratives of white innocence and precariously deracializes the consequences of 9/11 altogether.

When I started researching 9/11, I anticipated reading monographs about all kinds of books. Of course, I knew heavy hitters like Don DeLillo's Falling Man and Jonathan Safran Foer's Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close would show up often. But I quickly realized that the monographs that I read for exams and for my dissertation were profoundly white. They largely discuss white writers whose white characters inhabit a white world, one in which it is possible to ignore altogether integral responses to the attacks that people of color disproportionately and more dangerously live through. Even after twenty years of critical reflection, how does such a chasm in scholarship form? In search of answers, I pulled out some key critical works on the literature of 9/11 and the War on Terror, and started counting which ones examined works by writers of color. These were the books I examined:

- Kristiaan Versluys, Out of the Blue: September 11 and the Novel (Columbia University Press, 2009)

- Martin Randall, 9/11 and the Literature of Terror (Edinburgh University Press, 2011)

- Georgiana Banita, Plotting Justice (University of Nebraska Press, 2012)

- Ewa Kowal, The "Image-Event" in the Early Post-9/11 Novel: Literary Representations of Terror After September 11, 2001 (Jagiellonian University Press, 2012)

- Aimee Pozorski, Falling After 9/11: Crisis in American Art and Literature (Bloomsbury, 2014)

- Susana Araújo, Transatlantic Fictions of 9/11 and the War on Terror: Images of Insecurity, Narratives of Captivity (Bloomsbury, 2015)

- Charlie Lee Porter, Writing the 9/11 Decade: Reportage and the Evolution of the Novel (Bloomsbury, 2017)

I don't intend to demean any of these books; I value every single one of them for how they have shaped my understanding of the attacks and the literature they inspired. Each is a vital and generous contribution to the field, and I have cited them all with enthusiasm.

I chose these seven books for two principal reasons. First, all are by scholars who characterize contemporary literature as significantly defined by 9/11; in other words, they acknowledge the long shadow the attacks cast over the contemporary literary landscape. As Martin Randall writes at the beginning of 9/11 and the Literature of Terror,

The ten-year anniversary of the terrorist attacks in the USA on September 11 is fast approaching and the inevitable and necessary analysis of their impact has begun (if, indeed it ever went away). The historical significance of 9/11 appears relatively assured in that it provides us with a convenient starting date for the twenty-first century in that so many of the decade's most important events have been triggered by the attacks.1

The twenty-year anniversary of the attacks in 2021 offers a similar opportunity to reflect on their impact. And against the current unfolding crisis in Afghanistan, the anniversary has taken on an even greater significance, illuminating the tragic and traumatic consequences of nation building and imperial missions. Second, all seven monographs survey works that highlight 9/11 as a narrative, poetic, or (in a few cases) cinematic exigence. These books accord different analyses and stress the interstitial complexities of the terrorist attacks by incorporating a multitude of theories and close readings to relay how the infamous day lives on in the literary imagination.

Yet despite their variegated methodologies and interpretative lenses, these books remain devoted to a structure of whiteness that altogether eschews the reality of the post-9/11 era: Black and Brown people faced a brute vilification in ways that white people, quite simply, did not. These seven books are representative of the state of the field; twenty years later, having to do reparative work that seeks to acknowledge Black and Brown experiences in and contributions to the literary corpus is not only frustrating, but it speaks volumes about literary criticism's historical pervasive desire to center whiteness. In making 9/11 literary criticism's whiteness visible, to use Valerie Babb's helpful wording, we reorientate the narrative about the attacks to instead inspect the material circumstances of people of color. In order to ask how the looming specter of 9/11 has disproportionately affected Black and Brown lives, we must first ask why scholars are still resistant to addressing the material concerns of those lives.

A majority of the texts studied across these monographs are by white authors. This concentration on white voices underscores a single sidedness about the field's understandings about 9/11 literature and the attacks in general. Following 9/11, anti-Brown sentiment and legislation ran rampant. For example, the NYPD unfairly detained Muslim men, as HM Naqvi heartbreakingly writes about in Home Boy and Kamila Shamsie does in Burnt Shadows.Ignoring what people of color experience is a principal characteristic in what Moustafa Bayoumi calls War on Terror culture, which "promotes the seductive synergy of militarism and entertainment [ ... ] while rationalizing or ignoring the massive civilian death toll of the War on Terror."2 Literary criticism's whiteness bolsters this racist ecology.

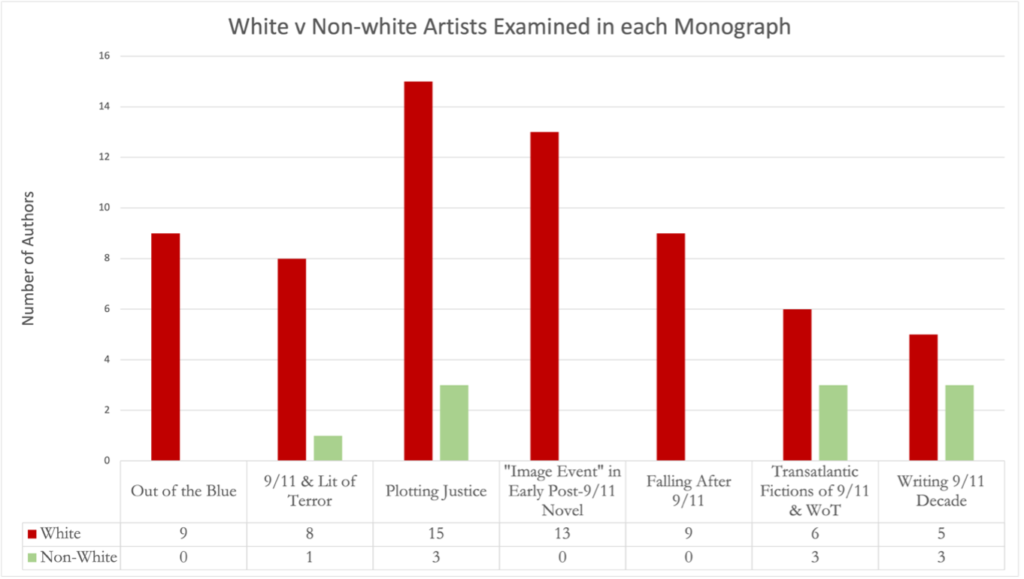

These seven monographs were published between 2009 and 2017 and come from five different presses; four are housed in universities, and one is a trade press with an academic imprint. Combined, the seven monographs examine 51 individual authors. Of the 51 authors, 45 are white. Beyond a tired insistence that defaults whiteness as the authoritative experience, these numbers exhibit literary criticism's tendency to fall into routines and ideologies of canonization. As long as white scholars continue to dominate classrooms and fields without considering their colleagues of color, we will continue to see this lapse back into these methods of imperial thinking that plague the academy.

88.2% of writers addressed by these seven monographs are white. Yet it certainly cannot be that non-white authors weren't writing about 9/11 between 2009 and 2017. Instead, the 88.2% figure rings the alarm of canonization, and reflects a failure to attend to the vital contributions of writers such as Colson Whitehead, Kamila Shamsie, N.K. Jemisin, Mohsin Hamid, Fatima Farhan Mirza, Nafia Haji, Laila Halaby, Porochista Khakpour, Tofik Dibi, and many others who investigate the effects of 9/11 and the War on Terror on Black and Brown people. The 88.2% centers white literary responses to the attacks, as if the attacks on the homeland were an affront to whiteness itself. Here, I follow Deepa Kumar who asserts that "the 'homeland' [ ... ] tends to be white, even if it is not explicitly articulated as such."3 The structures of this logic are dependent on the erasure of writers of color from the narrative, an erasure which, in turn, silences the voices of non-white victims of the attacks and the Forever War.

Erica Edwards compellingly notes that the periodization surrounding 9/11, treating the attacks as a historical rupture and a new era (the Age of Terror), "reproduce[s] the idea of a national literature based in white innocence and white, usually male, genius."4 Scholarship that only focuses on or primarily centers white authors telling the stories of white characters in white-dominated spaces reifies this white innocence. In turn, it absolves the United States of its imperial history and reiterates its hegemony, cultivating and certifying a kind of literary fantasy of American exception. As Toni Morrison writes in Playing in the Dark, "Deep within the word 'American' is its association with race. To identify someone as a South African is to say very little; we need the adjective 'white' or 'black' or 'colored' to make our meaning clear. In this country it is quite the reverse. American means white."5 Or as Valerie Babb posits in Whiteness Visible,whiteness is "everywhere and nowhere," securing "its synonymity with American identity."6 In their refusal or reluctance to engage with non-white writers, these canonical texts of 9/11 literary studies deal with race without addressing it. Race is presence in absence, a specter that, if made visible, quickly reveals the targeted dangerous, and racialized vitriol aimed at Brown and Black people of color in the wake of 9/11. It is imperative to mention that of the 45 white authors studied, 32 are American. As these seven monographs demonstrate, the enduring whiteness of scholarship emphasizes this association between "American" and whiteness.

The chart below (fig. 1) visualizes the discrepancies between white and non-white writers discussed in each monograph:

Studying these seven books that address over a decade of literary responses to 9/11, we might reasonably expect them to examine a diverse range of writers who have tackled the complicated social and political ramifications of the Age of Terror, ramifications which are inevitably racialized. Yet three of these texts don't investigate any writers of color. The chart makes visible the fact that despite the plethora of artists working on 9/11, white authors continue to overshadow conversations about historically and culturally resonant moments that largely occur in nations populated by Brown people. The books overwhelmingly privilege white writers to determine what the attacks mean. To read these critical texts is almost to assume that non-white people didn't experience 9/11, the War on Terror, or their consequences. While some of the books look as if they attempt to decenter whiteness, they in fact do not. In Writing the 9/11 Decade, Charlie Lee looks at five white writers (Richard Ford, Don DeLillo, Jonathan Safran Foer, Paul Auster, and Amy Waldman) and three Brown writers (Mohsin Hamid, Kamila Shamsie, and Nadeem Aslam). But even then, Hamid, Shamsie, and Aslam — lauded Pakistani-British writers — are relegated together into one chapter. Other writers, such as DeLillo and Auster, are given much more room to breathe freely in space of their own chapters.

The decisions we as critics make about who we give space to in our work reveal our agendas and what we view as important. Critics reproduce and amplify that white centricity in their choices about who to canonize in their monographs. It conjures a fantasy about the post-9/11 literary landscape that is regressively ahistorical and unmakes the work of scholars who tirelessly strive to include non-white authors in literary conversations and contexts. Literary scholarship must reveal these historical absences and look to uncover why they're missing from the narratives. Perhaps it is because criticism remains influenced by canonicity; after all, 9/11 resurged traditional values of white heroism.

To rectify this problem of erasure, scholars need to turn to narratives by non-white Americans and by international authors who address 9/11 and their effects toward people of color. For instance, Iranian-French writer Négar Djavadi's marvelous novel Disoriental (2018) decenters the United States from 9/11 and offers a glimpse of the historical build-up to the attacks, a perspective rarely studied by literary scholars. Protagonist-narrator Kimiâ notes on Friday, September 7, 2001 that "in four days the world would change, abruptly and for ever. In four days, the shock waves rippling out from the Iranian Revolution would make America tremble. Like in the story of Frankenstein, the monster assembled by the West from many separate parts would turn against it."7 (318-319). Djavadi's novel disorients historical narrative by indicting American empire. This perspective unravels the convenient notion of American innocence and instead centers how structural logics of oppression engender vengeful strikes back. If scholars acknowledge the imperial lead up to 9/11 at the hands of the West and engage with literature that narrativizes this history from the perspective of victims, they dismantle a kind of literary exceptionalism that all too often provincializes the material realities people of color endure.

Suddenly, then, we recognize that the Age of Terror is a misnomer. Terror thrives in the Global South and is an everyday experience for people of color in America — and it has been long before 2001. It isn't characteristic of the contemporary age; rather, it's endemic to the histories of people of color. When we work with, investigate, listen to, and recognize the experiences of the innocent noncombatants who suffer at the hands of imperialists, we unspool a narrative that feigns innocence.

So what would happen if scholars included the cacophonous range of responses to the War on Terror that have accented its consequences for people of color? Well, for one thing, it would make the contemporary literature field much more alive to the racial implications of recent historical calamity. It would also limn how the contemporary literature field continues to operate under structures and ideologies of canonization. As we consider what has happened in the last two decades, both historically and literarily, we see a more critical perspective toward the initial responses to 9/11; Bayoumi's The Muslim American Life, for example, substantively evidences how cultural responses to the attacks are rendered affronts to white masculinity. Literary scholarship must name and dismantle implicit and explicit white privilege in order to address the material harm people of color face to this day in the wake of 9/11.

This white centricity embedded in 9/11 literary scholarship reflects the social reception and perception of 9/11 and the Forever War outside academic circles. How is it that two decades after the attacks, the world still sees 9/11 and the War on Terror as a crisis towards whiteness? How is it that literary criticism about 9/11 still favors white men's perspectives? If, as many people claim, 9/11 was a historical rupture, situating a clear before and after, then surely, we should use its importance and power to start afresh, to progress not regress. The enduring white pattern I try to show in these statistics across seven otherwise very compellingly argued monographs accentuates the work that is left to be done — of what scholars necessarily must do to not only resist the urge of remaining in the harmful abyss of whiteness and patriarchy but to rewrite the narrative of our understandings about the Age of Terror. Whiteness, I want to be clear, is not the only avenue through which we can study 9/11 literary studies. The field not only privileges whiteness, but straight, able-bodied men as well — other hallmarks of canonization. It reverts, in more ways than one, to traditional understandings of literature and its role in shaping national identity. Ultimately, though, scholarly silence on such pervasive whiteness in the fields that inform our everyday lives, what we've dedicated our lives to researching, is the most damning thing of all. That complicity fortifies and emboldens whiteness as the norm and actively marginalizes people of color.

I want to conclude by offering a reading list: novels, memoirs, stories, drama, and poetry by authors of color who write about 9/11. This is by no means an exhaustive list. And many of these works have been paid substantial critical attention and appear in the monographs, but it pales in comparison to those by the likes of DeLillo and Foer. Many of these works have yet to be studied by critics, and as the dates attest, some came out before 2009, when the first monograph in my study was published. I include this list to begin mapping the future of 9/11 literary studies. Only when we begin to include a more inclusive and globally attuned archive of writers in our studies about the defining events of the 21st century will we be able to fully grasp their historical and cultural precedence.

- Colson Whitehead, Zone One (2011)

- Kamila Shamsie, Burnt Shadows (2009)

- Teju Cole, Open City (2011)

- Salman Rushdie, Shalimar the Clown (2005)

- Divya Victor, Curb (2020)

- Fatima Farhan Mirza, A Place for Us (2016)

- Wajahat Ali, The Domestic Crusaders (2011)

- Porochista Khakpour, Sons and Other Flammable Objects (2007)

- Porochista Khakpour, The Last Illusion (2014)

- H.M. Naqvi, Home Boy (2009)

- Allison Hedge Coke, Streaming (2014)

- Laila Halaby, Once in A Promised Land (2007)

- Nadeem Aslam, The Wasted Vigil (2008)

- Nafisa Haji, The Sweetness of Tears (2011)

- Laila Lailami, "Echo" (2011)

- Tofik Dibi, Djinn (2021)

- Helon Habila, "The Second Death of Martin Lango" (2011)

- Tahereh Mafi, An Emotion of Great Delight (2021)

- Jan Lowe Shinebourne, Chinese Women (2010)

- Monica Ali, Brick Lane (2003)

Jay N. Shelat (@jshelat1) is a PhD candidate at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, where he is finishing his dissertation about 9/11 and family. Jay's research looks at the way political upheaval shapes family. His work has appeared in or is forthcoming from Texas Studies in Literature and Language, The CEA Critic, ASAP/J, and elsewhere.

References

- Martin Randall, 9/11 and the Literature of Terror (Edinburgh University Press, 2011), 1.[⤒]

- Moustafa Bayoumi, This Muslim American Life: Dispatches from the War on Terror (New York University Press, 2015), 13.[⤒]

- Deepa Kumar, "See Something, Say Something: Security Rituals, Affect, and US Nationalism from the Cold War to the War on Terror," Public Culture 30, no. 1 (2018): 143-171.[⤒]

- Erica R. Edwards, "The Incessant War," Post45 Contemporaries, 11 Sept 2020. [⤒]

- Toni Morrison, Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (Harvard University Press, 1992), 47.[⤒]

- Valerie Babb, Whiteness Visible: The Meaning of Whiteness in American Literature and Culture (New York University Press, 1998), 168; 119.[⤒]

- Négar Djavadi, Disoriental, translated by Tina Kover (Europa Editions, 2018), 318-319.[⤒]