Legacies — 9/11 and the War On Terror at Twenty

In summer 2014, as Israel's war on Gaza intensified, Israeli actor Gal Gadot uploaded a selfie to Facebook that drew worldwide attention. It showed Gadot and her daughter covering their eyes after lighting Shabbat candles, with the caption "I am sending my love and prayers to my fellow Israeli citizens. Especially to all the boys and girls who are risking their lives protecting my country against the horrific acts conducted by Hamas, who are hiding like cowards behind women and children...We shall overcome!!! Shabbat Shalom! #weareright #freegazafromhamas #stopterror #coexistance #loveidf."1

The image's spread was fueled by the then-recent announcement of Gadot as the star of DC's Wonder Woman franchise, the latest instalment of which, Wonder Woman 1984, was released in 2020. The Independent declared: "Wonder Woman is officially pro-IDF."2 In May 2021, as Israel bombed Gaza again, Gadot posted to Instagram and Twitter, in more muted words: "My heart breaks. My country is at war."3 Her comments revived memories of her prior intervention, and sparked more frenzied posting on the Israel-Palestine conflict's digital front.

Gadot's posts drew attention not just because she is Israeli, but because she is a former soldier. She famously served two years in the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) as a combat fitness instructor, including during the 2006 Lebanon War. Gadot's two years of service are standard for women under Israel's compulsory conscription laws (men serve 32 months). In the media and online, Gadot is characterized alternately as a real-life Wonder Woman, whose IDF service was effectively training for the role, or as a "war criminal" complicit in Israel's violations of Palestinian rights. The debate on Gadot speaks to the role of popular culture in mediating metropolitan encounters with Israel and Palestine, and to the longstanding fascination of Israeli and international media with Israel's women soldiers. If Wonder Woman was banned in Lebanon due to Gadot's presence under the country's boycott laws, in the U.S. and elsewhere Gadot's IDF background offered the film's producers the gift of an authenticating narrative for its portrayal of righteous female warfare.4

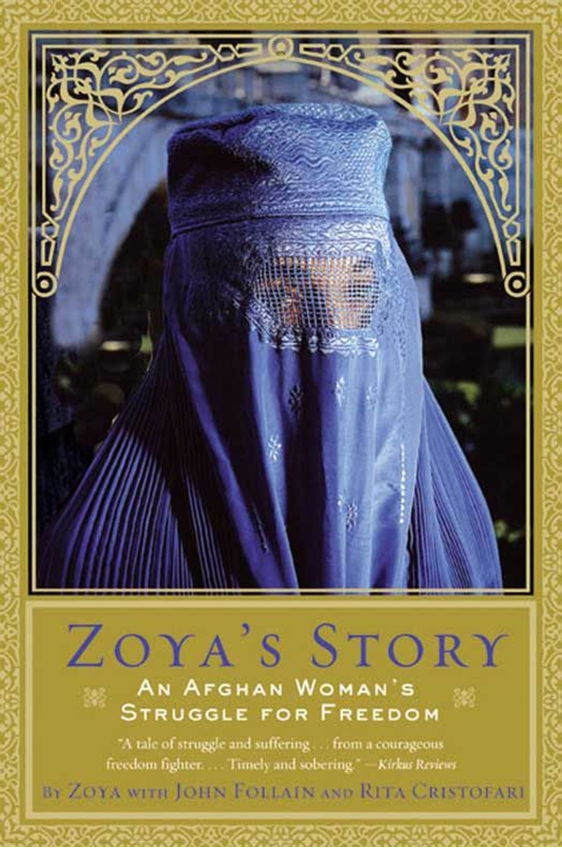

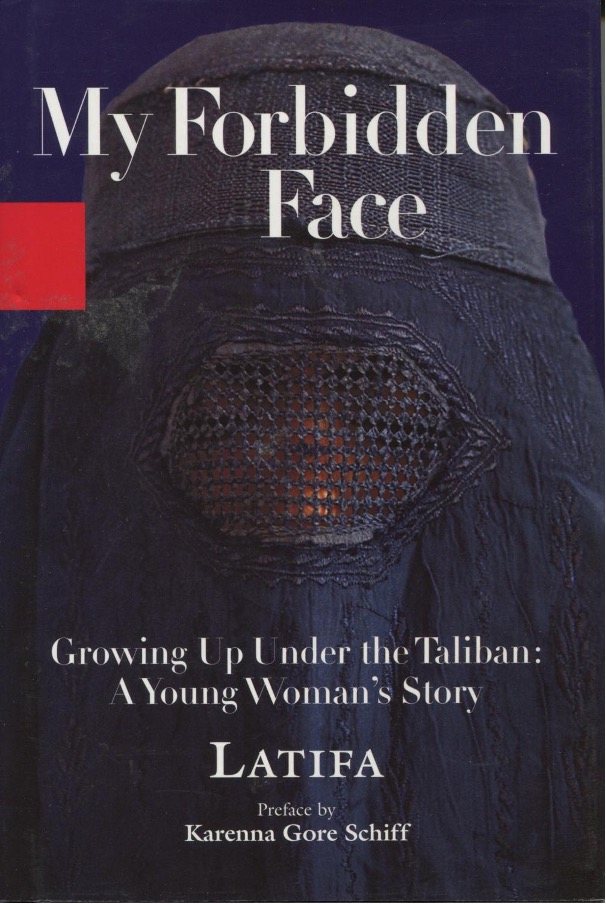

Israel's women soldiers and their pop-cultural representations took on new significance in the wake of the War on Terror — an enterprise sold, in part, in the name of women's emancipation. In 2002, commenting on U.S. military gains in Afghanistan, Laura Bush observed that "women are no longer imprisoned in their homes. They can listen to music and teach their daughters without fear of punishment, The fight against terrorism is also a fight for the rights and dignity of women."5 Her rhetoric exemplifies a common justification of the War on Terror as an intervention on behalf of Muslim women. This framing emerged in advance of the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, before being retroactively applied to Iraq after the failure to find weapons of mass destruction. A slew of dreary but often wildly popular memoirs and novels by and about women in Afghanistan reinforced the message, from Latifa's My Forbidden Face (2001) to Khaled Hosseini's A Thousand Splendid Suns (2007), notably via interchangeable covers featuring the burqa as a symbol of oppression, difference, and exotic fantasy (fig. 1).

Fig. 1: The cover images of Zoya, Zoya's Story: An Afghan Woman's Struggle for Freedom (2002) and Latifa, My Forbidden Face: Growing up Under the Taliban (2001).

At the time, Lila Abu-Lughod noted the resonances of this rhetoric with older colonial interventions that were framed as being on behalf of women while serving to legitimate colonial rule, from the banning of sati in British India to forced unveilings in Algeria by French authorities.6 Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak described these practices as "white men saving brown women from brown men."7 In the War on Terror, women, if not always white, joined the cause, as the push from liberal feminists for the "right to fight" paid off.8 Women soldiers were presented by the military and media as an asset in winning "hearts and minds", while stereotypes about femininity reinforced the invasion's humanitarian pretensions.

Israeli politicians were swift to align Israel's conflicts — with Hamas in Palestine, with Hezbollah in Lebanon, and with Iran — with the Bush administration's post-9/11 "clash of civilizations" rhetoric. After 9/11, Israel's then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon undertook a solidarity visit to New York and claimed that "the fight against terror is an international struggle of the free world against the forces of darkness who seek to destroy our liberty and way of life. Together we can defeat these forces of evil."9 By late 2001 and early 2002, Sharon could point to a series of Palestinian attacks and suicide bombings inside Israel as evidence for his claim that Israeli and American populations were engaged in the same "long and complicated war that knows no borders."10 The Hamas takeover of Gaza in 2007 further strengthened Israel's claims to being engaged in a common fight with the U.S. against Islamist terror.

Israel's reputation as the "only democracy in the Middle East" and, in turn, as a U.S. ally in the War on Terror, has long been bolstered by the apparent emancipation of Israeli women, with their conscription seen as the ultimate example of women's equality. Gender inclusion plays a similar role internationally to Israel's "gay-friendly" image, which serves, Jasbir Puar writes, as "a potent method through which the terms of Israeli occupation of Palestine are reiterated — Israel is civilized, Palestinians are barbaric, homophobic, and uncivilized."11 Israel's women soldiers, like those of the United States, appear as proof of Israeli "superiority over the backwards, misogynist enemy," understood as neighboring Muslim-majority Arab countries, Iran, and the Palestinians.12 The IDF is not in fact a bastion of gender equality; sexual harassment is endemic and women rarely occupy prestigious positions.13 Nevertheless, "femonationalism" shapes Israel's self-image and reputation internationally, reiterating its position on the side of the modern West and smoothing over its violence against Palestinians.14 This is reproduced through pop culture like Wonder Woman, where the "empowering identificatory pleasure" the film gives to women audiences translates back onto Israel via Gadot's ex-military status.15

Gadot's Wonder Woman styling as a powerful warrior for justice draws on the "erotic militarism" that has long shaped representations of IDF women, a trope that took on new meanings in the War on Terror.16 As Chava Brownfield-Stein notes, visual representations of Israeli women soldiers often evoke an aesthetic of military glamour and desirability while normalizing militarism by blurring the boundaries between military and civilian life.17 By the early 2000s, images of IDF women blended the third wave's "choice feminism" with ironic postfeminism. If Gadot is now positioned as a heroic (but still sexy) fighter for women's empowerment, in 2007 she featured in a notorious Maxim magazine spread of IDF women soldiers, arranged with the Israeli consulate in New York in response to poor image of Israel among young American men, who saw it as a land of conflict.18 This was perhaps unsurprising in the wake of the 2006 Lebanon War, itself justified as part of a regional "War on Terror," during which Israel wrought devastation on civilians and civilian infrastructure.

The Maxim piece began: "They're drop-dead gorgeous and can take apart an Uzi in seconds. Are the women of the Israeli [sic] Defense Forces the world's sexiest soldiers?" Yet little distinguished the images from Maxim's usual fare. In these images, feminism is both invoked and disavowed. They exist because of Israel's seemingly egalitarian conscription of women, while in the post-9/11 climate images of "empowered" Israeli women voluntarily stripping for the camera contrast implicitly with the stereotyped status and forced covering of women under Islamist rule. The images also provocatively invite feminist censorship, bringing feminists into the "public relations war." Any threatening or masculinizing elements of military life are removed. There are no phallic guns to remind us of these women's role in enacting violence, no shapeless uniforms to cause gender confusion among straight male readers, and Gadot is markedly scrawnier than in her Wonder Woman role. The images reflect the doldrums feminism found itself in in the early 2000s. Used alternately to justify starting a war or buying a new handbag, feminism's evacuation of meaning mirrored the wider cultural wasteland of the era.

With the rise of smartphone technology in the 2010s, visual representations of women IDF soldiers shifted again. Soldiers' selfies often went viral - particularly during Israel's regular and devastating assaults on Gaza, when metropolitan audiences became newly fascinated by Israel's women recruits. While the militarism of the Maxim portraits was premised on concealing military realities, these selfies brought military aesthetics into the erotic frame, even if they remain distanced from the battlefield. Women soldiers stripped for the camera, accessorized with helmets, khaki shirts unbuttoned seductively low, guns draped across their chests, or pro-IDF slogans and hearts daubed on their body. The disciplinaries that these soldiers received failed to dent the virality of clips such as "Watch Female Israeli Soldiers Twerk With Assault Rifles."19

These images are part of what Adi Kuntsman and Rebecca L. Stein describe as "digital militarism," or the way that social media tools increasingly normalize and entrench Israel's occupation in the twenty-first century.20 In 2021, IDF thirst traps have migrated from Facebook, Instagram and Tumblr to TikTok, where they solicit desire and identification from a youthful population that increasingly sympathizes with Palestinians. If Maxim presented the IDF's top glamazons waxed, polished and photoshopped into an unattainable ideal, the amateur porn of bored soldiers plays a different role, personalizing and humanizing Israeli warfare. These selfies show how occupation has become woven into the fabric of the everyday, both for their creators and for their international consumers, who see these images as we doomscroll our feeds on trains or late at night.

In 2010, a darker dimension of sexy selfies emerged. As Kuntsman and Stein discuss, that summer Israeli bloggers publicized a series of images posted by recruit Eden Abergil to her Facebook account in which she posed, pin-up style, with blindfolded and handcuffed Palestinian captives.21 The images prompted a furor in Israel that reached the international stage, where Abergil was inevitably compared with Lynndie England, the U.S. soldier infamously pictured torturing Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib in 2003. Far from enacting a kinder, gentler form of war, as liberal feminists had assumed, Abergil and England used their gender to heighten the humiliation of male prisoners. While the U.S. and Israeli governments portrayed each woman as a "bad apple," commentators pointed to these practices as a structural feature of American and Israeli warfare that gave the lie to claims of the virtue of each country's War on Terror.

If the images discussed above channel the visual language of erotic militarism, the film and literary portrayals of IDF women most recently acclaimed in the U.S. are decidedly unsexy, and point to a different phase in the relationship between representations of IDF women and the War on Terror. Israeli director Talya Lavie's film Zero Motivation [Efes beyahasei enosh] (2014) and Shani Boianjiu's English-language novel The People of Forever Are Not Afraid (2012) are dominated by a sexual embarrassment, playfulness and desperation that reflects their teenage protagonists' urges and anxieties. Their bored, cowardly and gawky protagonists contrast with the images of noble, brave, and glamorous women soldiers found in Israeli national culture and exported internationally. Both have been read as a form of "resistance" to Israeli militarism, yet they have more in common with the representations discussed above, and the rhetorics they instantiate, than first appears.

Zero Motivation follows bored teenage recruits on a remote Negev Desert base as they shred paper, sing pop songs, cry, fall out, dream of Tel Aviv's Azrieli Mall, or try to lose their virginity. Zero Motivation was widely lauded, winning Best Narrative Feature at Tribeca Film Festival and six Ophir awards in Israel, and is now being adapted into a series for BBC America by Amy Poehler, co-produced by Lavie and Natasha Lyonne.

Boianjiu's novel The People of Forever Are Not Afraid similarly focuses on a group of friends doing army service in mundane roles who dream about crushes, watch American films and TV (Mean Girls; The West Wing; Sex and the City), and skip duties to meet at the mall. The short stories it was based on were published in the New Yorker and Vice and made Boianjiu at 25 the youngest recipient of the U.S. National Book Foundation's 5 under 35 award. In the UK, The People of Forever Are Not Afraid was longlisted for the Women's Prize for Fiction.

If Gadot's Wonder Woman reflects an older caricature of Israeli military sexiness and power transformed for the girl boss era, Lavie and Boianjiu's awkward, underachieving recruits have more in common with the characters of Lena Dunham's Girls, as Poehler's hiring of one of its writers for her adaptation suggests. Lavie and Boianjiu's characters, like Dunham's, are in a transitional stage of their lives, in this case the rite of passage of IDF service, while they are as self-involved as Dunham's protagonist Hannah Horvath, an effect heightened by Boianjiu's use of multiple first-person narrators. Their voices blur, echoing the army's effacement of individuality and evoking an archetype of the teenage girl that draws the novel's target market of metropolitan Anglophone women into a sense of collective identification.

Sexuality in these works is a source of endearing and irreverent humor, echoing Dunham's famous self-abjection. In one scene of The People of Forever Are Not Afraid, friends Gali and Avishag inadvertently provoke a diplomatic incident by lying naked on the Israeli side of the border with Egypt, prompting Egyptian guards to masturbate uncontrollably.22 This absurd event makes Gali and Avishag appear relatably naïve and incompetent, increasing their appeal in the context of a popular metropolitan feminist politics that accepts failures and mistakes, as embodied in Dunham's show, over attaining the unreachable demands of "Lean In" liberal feminism. At the same time, the scene suffers from the same limited racial politics for which Girls was often criticized, inflected by the "particular sexualized racism of the War on Terror."23

Boianjiu's guards are portrayed as unable to control their sexual desire, to the extent that they are compelled to satisfy it immediately, without the girls' consent, and, pointedly, together. This recalls liberal feminist and homonationalist discourses on the War on Terror in which Islam's supposed hang-ups about sex, an old Orientalist trope, cause poor treatment of women and queers. The men's implied queerness adds to their perverse sexualization while making them the butt of the joke for liberal readers.24 The girls' misdemeanors show their belonging to a sexually liberated secular culture, but the guards' behavior is represented as a pathological trait of Arab Muslim men, as in their comically antisemitic claim that it is "all the Jews' fault [ . . . ] a deliberate trick, a new Israeli evil strategy."25

If Egyptian soldiers are portrayed as repressed voyeurs, Palestinians get an even rawer deal. They are largely absent from Lavie and Boianjiu's works, just as the conflict is minimized. These absences speak to the success of the War on Terror's narrative frameworks: the enemy is so obvious to metropolitan audiences that it only needs to be signaled, and this one-sidedness goes unquestioned even in critically-acclaimed works. In Zero Motivation, the closest thing to onscreen action is a staple gun fight after one protagonist tries to delete Minesweeper. In Boianjiu's text, Palestinian are terrorists, an anonymous mass at checkpoints, or cynical protesters asking to be shot to get press coverage, risking their own child's life in the service of a fanatical politics. Boianjiu's interest lies instead in the traumatic after-effects of military service on young Israelis, echoing the preference in U.S. mass culture for War on Terror narratives about the experiences of American soldiers. While these are important topics, this focus marginalizes populations who suffer military invasion and occupation most directly. Lavie and Boianjiu's use of inept teen girl protagonists heightens the effect: we are encouraged to identify with and want to protect soldiers, but not Palestinians.

Representations of female IDF soldiers tell us about another dimension of how war has been reconceived in the post-9/11 era as a feminist project. These images and narratives underscore the sense of a collective "us", Israel, the U.S., and its allies, with shared feminist commitments, in the face of an enemy other whose exemplary sign of backwardness is its threat to women and girls. Gadot's Facebook post evokes the stereotypes of the violent Arab, Muslim man, the Muslim women who need saving, and the heroic, gender-balanced Western military forces (Israel's "girls and boys"). The ongoing popular feminist revival has opened up new modes for representing IDF women and potentially questioning the links between liberal feminism and militaristic cultures. Lavie and Boianjiu replace erotic militarism with characters who are as uncomfortable as soldiers as they are with their sexuality. Yet in the end, the teen girl soldier is not so far away from the supermodel with a gun.

Hannah Boast (@hannahkateboast) is Assistant Professor and Ad Astra Fellow in the School of English, Drama and Film at University College Dublin. Her book Hydrofictions: Water, Power and Politics in Israeli and Palestinian Literature was published by Edinburgh University Press in 2020.

References

- Gal Gadot, "I am sending my love and prayers," Facebook, July 25, 2014. [⤒]

- Jenn Selby, "Wonder Woman Gal Gadot on Israel-Gaza: Israeli actress's pro-IDF stance causes controversy," The Independent, August 2, 2014.[⤒]

- Gal Gadot, "My heart breaks," Instagram, May 12 2021..[⤒]

- Catherine Baker, "'A Different Kind of Power'?: Identification, Stardom and Embodiments of the Military in Wonder Woman," Critical Studies on Security 6, no. 3 (2018): 359-365.[⤒]

- Cited in Lila Abu-Lughod, "Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving? Anthropological Reflections on Cultural Relativism and Its Others," American Anthropologist 104, no. 3 (2002): 783-790, 784.[⤒]

- Abu-Lughod, "Do Muslim Women Really Need Saving?"[⤒]

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, "Can the Subaltern Speak?" in Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 271-313, 297.[⤒]

- The Iraq War saw the capture of the first African-American woman prisoner of war, Shoshana Johnson.[⤒]

- Cited in Joel Beinin, "The Israelization of American Middle East Policy Discourse," Social Text 75, no. 21 (2003): 125-139, 125.[⤒]

- Cited in Derek Gregory, "Palestine and the 'War on Terror,'" Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 24, no. 1 (2004): 183-195.[⤒]

- Jasbir Puar, "Citation and Censorship: The Politics of Talking About the Sexual Politics of Israel," Feminist Legal Studies 19 (2011): 133-142, 139.[⤒]

- Saskia Stachowitsch, "Feminism and the Current Debates on Women in Combat," E-International Relations, February 19 2013. [⤒]

- See Edna Lomsky-Feder and Orna Sasson-Levy, Women Soldiers and Citizenship in Israel: Gendered Encounters with the State (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018).[⤒]

- See Sara Farris, In the Name of Women's Rights: The Rise of Femonationalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).[⤒]

- Baker, "'A Different Kind of Power'?"[⤒]

- The phrase is Chava Brownfield-Stein's in "Visual Representations of IDF Women Soldiers and 'Civil-Militarism' in Israel." In Militarism and Israeli Society, edited by Gabriel Sheffer and Oren Barak (Indiana University Press, 2010), 304-328, 305.[⤒]

- Militarism and Israeli Society, 305.[⤒]

- Herb Keinon, "Israel to put its babes forward in Maxim-um PR effort," Jerusalem Post, March 22 2007[⤒]

- Ryan Broderick, "Watch Female Israeli Soldiers Twerk With Assault Rifles," Buzzfeed, June 13 2013. [⤒]

- Adi Kuntsman and Rebecca L. Stein, Digital Militarism: Israel's Occupation in the Social Media Age (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2015).[⤒]

- Kuntsman and Stein, Digital Militarism, Ch. 3.[⤒]

- Shani Boianjiu, The People of Forever Are Not Afraid (London: Vintage, 2014), 148.[⤒]

- Gargi Bhattacharya, Dangerous Brown Men: Exploiting Sex, Violence and Feminism in the War on Terror (London: Zed Books, 2008), 9.[⤒]

- See Jasbir Puar, Terrorist Assemblages: Homonationalism in Queer Times (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), Ch. 1.[⤒]

- Boianjiu, The People of Forever Are Not Afraid, 148.[⤒]