Leaving Hollywoo: Essays After BoJack Horseman

For Pam Thurschwell

The "meanwhile" that spreads out an aesthetic world across many ongoing situations puts brakes on the advance of the protagonist plot line.1 Dilating time, meanwhile interrupts the growing pressure to get to consequences and, multiplying zones, allows in multiple tones for speculation not just about futures, but also about living the relation of causes to effects and effects to yet unenumerated causes emerging in the present. In this essay, reading for the meanwhile allows for focusing on the lateral movement across what, in pop culture, are often called A, B, and C plots: I am not presuming the priority of any plots.

BoJack Horseman is held together by legal and moral crimes that are personal and pervasive, normative and structural. It is also a workplace comedy, documenting the ridiculous and destructive inducements of the culture industry. It is also a mental health dramedy, merging the comic mechanicity of character with the mercurial stuckness of the anxious and depressed.2 The device of the cliffhanger haunts the everyday of the series world: there's no affective coasting for the injured and injurious.

I propose to call BoJack Horseman a traumic, and define the traumic as a genre that milks the formal likeness of trauma and the comedic: in a traumic, the beings under pressure and disturbed by what's happened around them are usually destined not to be defeated unto death but to live with the light and heavy effects of damage, still acting, being acted upon, and trying to keep things moving, which is to say, surviving. Think about the sharp shocks of slapstick, quick wit, and the bodily hit that might be comic bumps, or not. Think about the ridiculous meanness and sarcastic reason of institutions and the contemptuous classes. Think about the features of inequality in which comedy punches down on racialized, sexualized, working, and other outsider bodies.

The affectively mixed directions of the traumic say something about the co-presence among what look like antithetical aesthetic registers, not just in art, but in the life genres of the random encounter, ongoing intimacy, and sensually jolting structural violence. In the traumic, death hovers weightily in the shadows of life as one of life's meanwhile plots, but finitude is not the framework for the state of being and affect in the livewire genre I'm offering. As Walter Benjamin writes, not even the dead are safe.3 For example, in BoJack's penultimate episode, "The View from Halfway Down," the dead remain in affective and aesthetic life: those who have died during the series reappear in a fugue state of BoJack's after a serious bender that ought to have killed him. In the traumic, the story takes jump cuts across plots rather than shortcuts to satisfying ends. Comic and awful frame-breaking pile up. Worlds are flooded with ironic, satiric, and melancholic airs. Usually, in the traumic, bodies, institutions, and senses take hits but recover in a startle or a fog.

This is why, in the traumic's aesthetic and affective tangle of dark and funny upset, the problem is that beings and infrastructures do not die but live on.4 An injury can feel heavy and insurmountable but that very looming stuckness can both amplify the distortions of suffering life and induce spontaneous laughter, smirking, and shrugging, even when the trigger may not be funny. The defining gaze of the traumic faces its world with an almost unbearable realism. But realism is also surrealism in the place of injury's affective spread. The traumic draws on what's dark about the situation comedy and ludicrous in the situation tragedy.5

BoJack and the character BoJack splay across these genres and states. Sarah Lynn, a young actor in BoJack's 1990's situation comedy, Horsin' Around, dies overdosing in BoJack's presence years later and with BoJack's drugs and knowledge: in Season 6 this cause begins to have effects that slow down time and turn recursivity into a curse. In this way, this traumic is also a thriller, awaiting the consequential revelation of his careless murderousness. Maybe all traumics are thrillers of the blocked truth, leaking. In a traumic, the truth sets no one free in ways that at times produce comedy.

The show uses the cut across plot lines to screw up the focus and movement of backstory, the story arcs from the recent and receding past whose traces affect the shape of the present. In Season 6, though, the final season, every protagonist makes time and gets involved in some life-repairs that allow for the series to take a moment without finding relief in resolution. In Season 6, some details finally stick and reshape the meanwhile infrastructure of the cartoon world. Some protagonists have spent the series feeling helpless, seeing themselves as effects of what life has done to them rather than as causes of those effects. In the final season, as the show wraps up, they decide to become genuine protagonists of their own lives: but the ideology of being responsible and taking control that pervades the reparative wishes of this season produces even more tragicomedies of frustration and damage.6 Virtually every major character has a panic attack, a dramatic unravelling of defenses. This may feel bad but it isn't entirely bad. Defensive devices have to loosen for something new to happen.

This essay attends to two kinds of loosening, aesthetic and affective, that take place during the tightening arc of Season 6, when the story of Sarah Lynn's addictions and death finally adds up to something. Until the final arc, the details of the former child star's destruction have woven into the other schemes, relations, and foolishness of this cartoon world. But then the genre of the public scandal appears on the scene to make a home for what's been lived with. Characters have kept insisting that the full story has never been told, while in fact it has fallen multiple times from loose lips — during BoJack's drunken benders, in bystander reports, and finally from Mr. Peanutbutter's enthusiastic mouth. Peanutbutter is the passive-aggressive dog-being who finally spills the beans to a scandal sheet reporter adept at the seduction of giving attention: good dog!

I bring up the meanwhile plot line's interruptive organization of the artwork's fluctuating proceedings because "Good Damage," the episode on which I am focusing, is a crucial part of bringing the series to a soft landing that doesn't quite touch down, allowing for a plane of suspended existence for the friendship group. That plane is endemic to the traumic. But to get to this space, the show's established forms of aesthetic, affective, and historical continuity need to be released from their repetitions.

To get to this unraveling, the show coordinates many disruptions of its established modes of stylization. First, the writers thematize explicitly the aesthetic and affective problem of trying to tell a story that has never had the room to be one. To reach the animated suspension of life at the close that is not an end, "Good Damage" disturbs contemporary hierarchies among media formats. This medium instability adds to the interruptions that have constituted the show's ordinary in the meanwhile of incidents, wisecracks, worries, backstories, food, and also, importantly, the bump of affective states. The episode turns media forms into plot devices: as it sutures worlds into plots about the breakdown of what's ongoing, the old school telephone, the newspaper, and the writing page return to make information dramatic.

To demonstrate how hard it is to dissolve the defenses that accommodate the world and protect the aesthetic pattern we call our personality, the episode moves formally between the smooth, silent continuities of the cartoon's usual digital mode and the analog gears of a film projector, which we hear clicking intermittently throughout. Along with this, "Good Damage" uses color to access the truth of pervasive psychic brokenness that also rides across the representational surface. The art director of BoJack, the illustrator and comics artist, Lisa Hanawalt, usually mines a rich, bourgeois-modernist color palette to make the intensely destructive and will-to-survive energies of the show's world into an atmosphere that absorbs events more than the characters do.7 Here, along with moving from digital video to analog film sound, the episode style switches from its Colorforms texture into a creative dystopia represented by typescript and black and white pencil-drawn scenes.8

Only once before has the series used alternative style to demonstrate the long and short tentacles of affective disruption: in "Stupid Piece of Sh*t" (Season 4, Episode 6), BoJack lives with an inner voice that storyboards itself in construction paper colors that emit the kind of intense self-hatred that proves self-knowledge can be calcifying, not transformative.9 "Good Damage" echoes in its use of lenticular style a disturbance akin to the traumic form of some graphic novels.10 There is always a backstory to the eruption of alt-textures that provide a path to alt-trajectories and tones.

The specific backstory here involves memoir. The episode's focal character, Diane Nguyen, has turned to writing a book of personal essays. Its not-very-successfully-working title is One Last Thing and Then I Swear to God I'll Shut Up About This Forever: Dispatches from the Frontlines of the War on Women: Arguments, Opinions, Reflections, Recollections, The Razor Tax. This is to say she begins by talking around what the memoir will be about through apology, defense, shame, cliché, and genres of self-reflection that trail off quickly. But in this episode the title of the unwritten book shifts to Good Damage, which is all a traumic's subject can really hope for, not that Diane actually finishes the memoir.11 When she confesses the abandonment of her immiserating, life-saving project, it's with the phrase, "funny story about that."

Diane's attempt to write this book builds to a life-breakdown that appears as a block: a writer's block.12 A writer's writing block does not mean there's no writing. It can also induce writing that is not the writing that the writer wants and does not want to do.13 It's funny that, in the meanwhile of this episode, the name of the reporter who gets the story that pushes everyone toward pushing out BoJack's truth is named Paige, who is drawn and performed as an amalgam of Rosalind Russell and Katherine Hepburn in their manic bossy phases. The revenge of Paige's page is to unravel the show's defenses against consequences: there's law, there's the event of the scandal, the murder-threat to a reputation, and there's a suddenly moral judgment that shifts the atmosphere of what can be done. Sarah Lynn's details, with their long hooks into other meanwhile plots, appear finally as monuments in scandalous fonts rather than folding into quips that reappear as light haunts in other episodes. Diane's home-movie sounding memoir and typewriter font pages exact a different revenge. Diane is not so lucky to have her story rescued by genre.

For all six seasons of BoJack Horseman, Diane has been a writer. In Season 1, her character enters as BoJack's ghostwriter. Later she takes on work as a social media journalist, then gets fired for her anticorporate research. None of what she takes on is easy or clean, but Diane has a commitment to saying what she sees one way or another, and the process of writing itself does not add to the drama. In Season 6, the biographical ghostwriter tries to take her turn as an autobiographer: yet she's still somewhat of a ghost to herself, a past made of testy moments that don't add up.

The challenge is to say the truth in a way that's transformative and sustainable, to expose a new vulnerability that can better sit with the unbearable that must be borne. Diane's desire to blame others and the world for their threats and irritations produces anxiety in the form of a comedy of misery and self-destruction: affective slapstick. The challenge is to not blurt out the truth in the bubble of ironic commentary but to write her way into story and out.

When she turns her attention to herself to write the book, all she finds is that everything wants to be said and to go without saying. She finds that her episodes provide thin eloquence, remainders of a non-narrative affect-world of tenderness and defense. It's a lot of pressure. Autobiography feels like a threat. It upends Diane's lifelong focus on other people's damage and desire: it feels shattering to try to write not just the truth of causes but to lay out the pervasive effects on her. When does the riff become a world animated by the energy of its thought?

In short, autobiography incites here so many kinds of exposure at once: a coming to terms, a settling of scores, a bath of self-doubt, an uncloseting, a willed exposure to what has gone without saying. The effects of this exposure on Diane are physical, in which I include the mental and emotional. The episode opens at a Chicago Cubs-style "Baby Animals" game, where she produces bitter political commentary on Chicago-style, environmentally destructive corporate food to Guy, her wonderful Bison-boyfriend; then there's an insert in the mode of a Partridge Family, 70's style pop art video in which she eats a plump Chicago-style hotdog while performing being happy on "happy pill" antidepressants. In the process of re-engaging with herself, which takes place across many episodes (starting with Season 6, Episode 5), Diane's body has changed visibly: as she tries to be in real time with her emotions and suffering, antidepressant side-effects reshape her, turning her into a person who eats and regurgitates mainly off-camera, while living amid the scattered litter of the very packaging she hates. Generally she gorges food throughout in a failed drive to bury or choke her unremitting sadness. She describes depression as a bottomless hole in the episode "The Face of Depression" (S6, E7): you can either take drugs to interrupt depression or you can just

. . . flip over the nothing and underneath there's more nothing. Then you flip over that nothing and there's more nothing after that. So you just keep flipping over nothings, all your life, because you keep thinking under all that nothing there's gotta be something, but all you find is nothing.

She's being flip, but not. In the traumic, every grounding floor turns out to be a hollow chamber in a hall of mirrors. Diane's frank pleasures come with a self-brutalizing cost. To become inward facing is to become self-defacing. The show's interruption of its standard smooth style helps it get at the psychic costs of holding onto and letting go of the veneer of personality made for others' comfort and diversion.

When Diane eats emotionally and gets bigger and rounder, she becomes a species like everyone else in the show, where animality mostly goes without saying because the characters are defined by their appetites, not by species. Only when she tries to be her version of a protagonist are her appetites released from the defenses that make her seem reasonable and reliable, in proximity to but outside of the traumic as a form of life. It is not that she had no appetites before she turned her writing toward herself, but her defenses allowed her to see her pleasures as troubling and her life-destroying impulses as exceptions or as the effects of other beings' actions. Wanting something actively, instead of in response, is overwhelming for her, though. Previously she had married the other major character who doesn't seem to have an unconscious, the enthusiast, Mr. Peanutbutter. She had seemed to sidle into the marriage. They spent it talking across each other, and although he's named after a food, she has little taste for him — besides the sex. (BoJack Horseman does not respect sex.)14

Finally, when Diane tries to craft her own plot in this writing block episode she too gets to be an unconscious on parade, no longer a sensible person with depressive tendencies who provides a foil to the other dysregulated peers who can comment on themselves but not with a reflective depth that would make those selves impossible or different.15 Opened by writing the way some people are opened by love, she becomes one of them, an appetitive mess.16 It's comedic and dramatic, shadows the tragic, and ultimately displaces the ambition that started it all. We should have a comedic concept like a "happy swerving" since it reaches nothing like an ending.

This is abstract, because the appetites are abstract until they find objects to act on. To reactive protagonists, objects seem like the cause, the trigger: I couldn't help myself — it was calling to me and I submitted, or it was threatening me and I defended myself. Defenses that project power onto the magnetizing object keep the subject from experiencing themselves as formless and pulsating out of control. The minor characters in BoJack are standard situation comedy sidekicks triggered into repetition of the appetitive habit that makes them recognizable, comical and maladaptive, lucky or unlucky, and mostly lovable machines; the main characters suffer in their ways of living with appetites but in the final season they come closer to being educable. "Educable" is a sad pun here, since one of BoJack's plot lines in this final season is to make him a drama teacher at Wesleyan University who focuses on training actors how to move from imitating character through caricature to thinking how affective realism can energize even the silliest scene. To be educated into this perspective requires deep but comedic method acting: being able to feel all the feels of a situation however cartoonish the aesthetic world, engaging what's exemplified without leading with unimaginative defense and deflection. In the uncontrolled situation that makes something a traumic the main characters have no choice but to process the many moving parts of the gummed-up ordinary.

When Diane confronts her desire to write personal essays, the writing block produces symptoms and affects of doom and dread. As commentaries on the aesthetic block often note, the artist's feeling of worthlessness and a dark fate often follow the artist's expectation of ecstasy, truth, grandiloquence, or more simply the pulse of the need for further satisfaction, which is another way of talking about pleasure. Symptoms, though, are intrusive. As scenes of opacity, they generate thought.17 A symptom is both an expression of a process and a blockage against accessing what's causing it.18 (A cough could mean so many things; an addiction can have many motives; in both cases the very disorganization of the symptomatic subject makes people want to over-organize causality.)

Diane names, as the causes of her abjection, her father's sexist high standards, biting contempt, and patriarchal preference for protecting his sons' ego strength. Ironically but not, the very practices that damaged her reappear in her life as commentator, in her skill at describing anyone and anything critically, including herself. She's kinder than her father is while also being a passionate, biting judge. But as with all of the characters bearing backstory, auto-critique has acted as a premature foreclosure, a defense against any form of knowing that might disturb the personality machine. Admitting or confessing are not the same as transformative knowing. So the emergence of an unravelling style in this episode is a symptom that both reveals and protectively distracts. For Diane it takes the form of diaristic self-punishment; she moves one step forward toward truth on the page and then backs off in earthquakes of self-doubt; performs stand-up admissions to whoever's an audience, including quipping about herself to her split-off self — a style that both admits what's awful, keeps her from changing, yet ultimately saves her from some abysses.

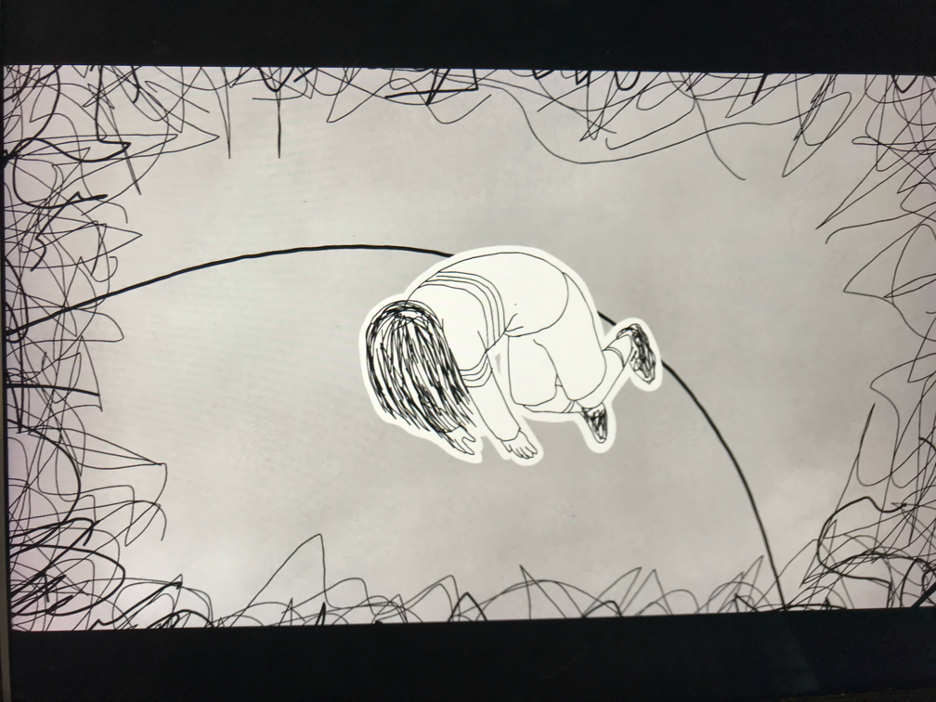

A US vernacular term for the state of being unreliable is "sketchy": as Diane tries to become a protagonist, she becomes visibly sketchy, a sketch. The show's mise en scène literally drains color and context from the image, now traced out in pencil. The old-school film medium clicks during a series of sketches featuring pencil doodles and a parodic pencil-drawn version of a bedraggled Diane who looks nothing like cartoon Diane — but has the same voice. In this medium and format, she relives the struggles of the past that remain active and unresolved; the sketches represent the intrusive ideation that keeps her from writing out her own narrative as a thing of her own shaping. The sketches are full of rhetorical questions dying not to be, whose very lonely separation from responses becomes increasingly desperate: "Is this interesting?. . . Is that something, is any of this anything?"19

But her statements and questions go round and round without finding traction: on the phone with her agent, Princess Carolyn, Diane keeps riffing in the hope that she'll find something to say about what the "is" of the book is. She's got nothing except the drive to wrestle the echo of the cruelty from bullies at home and school. But the world of the traumic is one step ahead of her, refusing the healing revelation-chain she seeks and instead composing a light and palatable palette she can appropriate and use to test the world. Who knows what would have happened if there weren't people checking in, not up, on her? That said, the unplanned acceleration of an alt-plot provides a meanwhile cushion that is, and is not, a solution.

Here are two linked examples. In "Good Damage" Diane hangs out at the mall to protect herself from crumbling the day away in bed and to lasso distraction into a focus on people watching and writing. In a mall it's inconvenient to move around once you've settled somewhere: forced to limit interruptive wandering and falling into sleepy fugues, the telephone is her linking object.20 On the phone Diane tells Princess Carolyn that her book is about trauma because, while sitting not writing in the mall food court, she hears a voice from the consensual real world say to a friend, "We have to look at trauma! . . . We totally have to look at Trauma." It turns out that she is sitting next to a women's clothing store called Trauma. Who needs an unconscious when the world's so giving with concepts that monetize self-division? Here, Diane lives in the historical present of the commodity form defined by possessive appetites: but the possessive is also self-dispossessive, a way of using an owned prosthesis, a thing or identity, to substitute for what's alive and disturbed. The biohistorical echo chamber of affective realism distills the world into scenes of conflict between drives toward and away from taking things in.

Yet in this very scene of "Good Damage," Diane finds a footing that interferes with her desire to be the focalizing subject of her own story without entirely trashing the project. Trauma's workers humiliate customers like Diane who want to fit into a size, spewing teen contempt at her. While she's in the dressing room she overhears the staff gossiping about thefts in the mall. Returning to her table, she goes into another daydream, a post-shopping fugue that protects her from her writing but not from her tremulous self-punishment. In the sketchy dream, a pencilled-Todd appears, telling her that her book is a complaint, boring and failing. He manifests a book called Whiny Diane's Tome of Bellyachin'. She protests and smashes him into the sketch of the book. What comes next is the third act of the story.

A character called Ivy Tran appears from the book's hollow, unwritten space. Her voice comes first: it's not Diane's voice. "This book is like 'bore me with a spoon,' Diane. You know the story of Gemberly, right?" The book title turns into The Story of Gemberly. It's a day's residue of the stolen wallet story from Trauma.

Ivy says that, like Diane, she's Vietnamese-American: she tells a story of coming to Chicago with her mom for a new start. She's purple-haired, post-punk, kind, aggressive, and searching. She enjoys figuring out the crimes against property the mall keeps suffering.

So the palette, medium, and content of Diane's dreamscape add yet another aesthetic dimension to this episode's metamemoir as well as to the schema of BoJack Horseman: a bare storyboard animated with a yet unfilled-out realism signified by a globe and the mall. Ivy is confident in her "I" and the protagonism to which being a detective gives shape. Diane, though, sees the character's narrative and her figure as unimportant, light work: a Young Adult fiction trifle. Guy insists that she's happy writing it because she can write it but Diane thinks that staying with Ivy's story means she'll never use her own suffering to help other bruised girls. What's the use if the trauma of her trauma is not foregrounded and transformed? At first Diane's symptoms get worse: vomiting, an analogue of the speech that is not writing, happens.

Without permission, Guy sends the fantasy that turns out to be a manuscript of its own — Ivy Tran: Food Court Detective — to Princess Carolyn. The friends argue and then have a heart to heart about the way an unapologetic, fun, frank girl character might not stage the confrontation, overcoming, and repair Diane seeks but could model a non-white, non-American migrant, inventively gendered and knowing, living a freedom that's cool and beautiful and smarter than everyone in a way that's unapologetic and does not involve the reproduction of trauma. Ivy's story begins in worlds of displacement and minor transgression but launches into commentary and hijinks marked by whip-smart glee.

The memoir fiction of Ivy Tran becomes a world Diane wants to be in, a "funny thing" she is making rather than fleeing. This new non-representational launching pad allows her to invent, rather than relive in order to prevent reliving. It leads with the comic part of the traumic while based, nonetheless, on the accompanying shadows made of lies, theft, and gossip. The experiment that occurs to Diane allows her to split a new way, to avoid self-destruction, and to accept help too: in other words, to live in the present of the meanwhile she makes.

I wanted to sit with the aesthetics of good damage that uses a surprising shift from the conventions of the digital cartoon world to a scene of sketchy Super-8 ideation with its lost beauty, regressive form, and absent-minded doodling amid desperation for the clean line and the rich surface on which a healed person could appear and appear to thrive without lying about the world. Diane does not achieve autobiography because, at first, what she wants is to circulate an exemplary defense for other girls like her. What she achieves instead is a tentative arc for a protagonist who takes the injuries of the world for granted and pursues them with the kind of a kindred interest that allows criticality and attachment to appear from the inside of a relation rather than the outside of the family, capital, class, and race-secured judgment. Curiosity about why and what for produces meanwhile as the other to the causal fortitude of the virulent blinder and the fist.

Just as there is no literal saving truth there is no formal solution or media platform to resolve the problem of living: no realism waiting for its story, no medium or style that reaches the utopia of successful form, if successful means something that erases the weight of the historical. This episode's meanwhile toggle across mediums, formats, and styles of making, living, and being loosens up the habit of personality and world-solidity. The traumic will not allow such confidence in appearance. It is a genre of the destruction of life that has no choice but to look expectantly at life.

Lauren Berlant teaches English at the University of Chicago, where her work has focused on collective emotion's forms of life. Recent books include the edited volume, Reading Sedgwick (2019); with Kathleen Stewart, The Hundreds (2019), 100 theoretical pieces on the ordinary, an issue of Critical Inquiry edited with Sianne Ngai, Comedy, An Issue, and Cruel Optimism (2011). Her current project is On the Inconvenience of Other People.

References

- The mutually informing infrastructure of the meanwhile in the realist novel and the temporal experience of the nation form have been long a topic in political, critical and literary theory, certainly since the debate between Benedict Anderson in Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (1983; London: Verso, 2016) and Homi Bhabha, "DissemiNation: Time, narrative and the margins of the modern nation," in The Location of Culture (London: Routledge, 1994), 139-170. Rei Terada has also written powerfully on the dynamic copresence of potential worlds in philosophical terms, in Looking Away: Phenomenality and Dissatisfaction, Kant to Adorno (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009). One could simply say that it's a plot "device" that may or may not be a gimmick, for as Sianne Ngai argues, a gimmick lies latent in every made thing in capitalism" and BoJack is nothing if not about people trying to be a kind of thing, an aspirational gimmick, until they break. Ngai's focus is on the gimmick as a thing and a judgment of external objects, however. BoJack relies on habits that defend and fail to defend, that injure and protect, developed from the survival drive that throws up the screen of personality that lives next door to trauma. See Sianne Ngai, Theory of the Gimmick (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2020), 5 and passim. [⤒]

- The mechanicity of character weighting down living being is crucial to Henri Bergson's scenario of animated being's ontological occupation of the comedic in Laughter: An Essay on the Meaning of the Comic, Trans. by Cloudesley Brerton and Fred Rothwell (New York: ç, 1911), 14-18.[⤒]

- On comedy as that which escapes the comforts of finitude, see Simon Critchley, "Comedy and Finitude: Displacing the Tragic-Heroic Paradigm in Philosophy and Psychoanalysis," Constellations 6, no. 1 (1995): 108-122. As for the dead being unsafe, see Walter Benjamin, "[N]ot even the dead will be safe from the enemy, if he is victorious," in "Theses on the Philosophy of History," in Illuminations, introduction by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn (New York: Harcourt, Brace and Jovanovich, 1968), 255.[⤒]

- In the final exchange of the series, BoJack utters a cliché, "Life's a bitch and then you die," but Diane gets the last word, "Or maybe life's a bitch and then you keep on living." A perfect epitaph to this essay's proposal for the traumic. [⤒]

- I discuss the situation comedy and situation tragedy in terms of television's The Office and the film and graphic novel V for Vendetta in Cruel Optimism (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011), 6-7, 176-177, 290-291. I learned from Bergson's Laughter that most things we laugh at are not funny. [⤒]

- I learned to think about the assumption of the protagonist position from Carolyn Steedman, Landscape for a Good Woman: A Story of Two Lives (New Brunswick NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1986), 15 et passim; Steedman learned it from Jeremy Seabrook, notably in What Went Wrong?: Why Hasn't Having More Made People Happier? (New York: Pantheon, 1978), 262. But they use the aspirational ideologeme of the "hero," whose inflation as a vehicle for agency is part of the problem of imagining protagonism as a way of life.[⤒]

- For a brief backstory of the BoJack project, see Chris McDonnell, "How BoJack Horseman Got Made: An oral history of TV's favorite alcoholic, narcissistic, self-destructive talking horse" in Vulture, the comedy newsletter of New York Magazine, September 4, 2018. This article is an excerpt from Chris McDonnell and Lisa Hanawalt, BoJack Horseman: The Art Before the Horse, introduction by Raphael-Bob Waksberg (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2018). Hanawalt's use of interior decorating in general and in the opening credits in particular involve variations on the haunting of crime, injury, and sorrow that subtract up to BoJack's life, providing the viewer with a silent mnemotechnology.[⤒]

- Colorforms were a US toy invention dating from 1951 that offered thin vinyl representations of a modernist bourgeois everyday life and a few fantasy worlds. With these pieces children could populate the set storyboards the company included. [⤒]

- BoJack's daughter, Hollyhock, is also in "Stupid Piece of Sh*t." The episode ends with her observation that her inner voice dramatizes self-hate and a persistent sense of world- abandonment. She asks BoJack if this excoriating voice is just a teenage thing, and he lies to her out of love: yes. The transgenerational trauma bruises of BoJack Horseman continue.[⤒]

- Classic traumics that use a friction among styles to perform the ambivalence and fragility of world-atmospheres and mental health in the meanwhile of existence include graphic narratives by Art Spiegelman, In the Shadow of No Towers (New York: Pantheon, 2004); Chris Ware, Jimmy Corrigan, The Smartest Kid on Earth (New York: Pantheon, 2000). Most graphic novels do not vary their visual style as dramatically as their content. But that can be an agent of the traumic's unpredictability too. As a counter-example, a traumic with a highly consistent style that nonetheless uses its visual predictability to perform surprising plot and affect jolts, see Ebony Flowers, Hot Comb (Montreal: Drawn and Quarterly, 2019); see also the dynamic of subtle scenic and perspectival twists amid the intense stylistic self-insistence of Nick Drnaso's work in Beverly (Montreal: Drawn and Quarterly (2016) and Sabrina (Montreal: Drawn and Quarterly, 2018). Obviously, this note is a gesture toward attention to the use of style and scene almost literally as agents against skimming the traumic's alt-world as though the reader can predict it. For an opportunity to test out how visual style in the comics can evoke an affectsphere that may or may not be subjective, and may or may not have a dominant affect, see Matt Madden, 99 Ways to Tell a Story: Exercises in Style (New York: Chamberlain Bros., 2005).[⤒]

- "Good Damage" comes from Diane's memories of Mr. Peanutbutter's repair of a bowl through the art of Kintsugi, which uses gold leaf to repair the bowl by making its damage beautiful. In the summer of 2020, it resonated with the phrase "Good Trouble" uttered by the Black civil rights activist John Lewis (1940-2020), which circulated as a way to think about the best kind of radical resistance to white supremacy by whatever means: violence, non-violence, and being inconvenient to the reproduction of its powers. Diane turns "Good Damage" into a version of "Good Trouble," heeding the call to reuse injury against the forces that made it by constructing an aesthetic form that makes injury not into a kind of scarred beauty or a mirror of power but a rough otherwise that relies on the counter-knowledge of the migrant, the displaced, the racialized, the gendered. She does this for a collective world that commercializes a political need. The political door is left open but the revolution has not been storyboarded. [⤒]

- The bibliography on aesthetic blockage is substantial, often starting with Marion Milner, On Not Being Able to Paint, introduction by Janet Sayers (1950; London and New York: Routledge, 2010). Milner's solution to try free painting is very much like what Diane learns to follow in this episode. The library of behavioral-psychology self-help books on this problem is interminable as well, all containing tricks that worked for someone.[⤒]

- Citations of The Shining (Kubrick, 1980) that parody the protagonist's repetition paralysis in the phrase, "all work and no play makes Jack a dull boy," appear here on Diane's laptop as well. The David Markson novel, Reader's Block, is also relevant here, as the attempt to over-control emotional disorganization engenders tragicomic threat and tone, before it becomes pure tragedy. David Markson, Reader's Block (Champaign, IL: Dalkey Archive 1996). [⤒]

- It would take many detailed pages to support the statement that BoJack Horseman doesn't respect sex. To summarize: The character BoJack wants contact but destroys the contacts he makes; his parental history as well as his own suggest pretty strongly that any relationship in proximity to BoJack that involves procreative or appetitive sex is doomed to become injurious, unethical, unloving, or just a bad idea. For Princess Carolyn work takes up libido: sex is about procreation, not about pleasure or bonding. Thanks to the assistant's strike in Season 6, she finally bonds with her baby, Ruthie, which means that she schedules every third Friday off to be with her. For Mr. Peanutbutter and Diane sex is about lust and cluelessness, mere wrongness. Mr. Peanutbutter's second wife, Pickles Aplenty, is completely happy-shameless in her puggish appetites: where the appetites go she attaches monogamously. Peanutbutter remains clueless about her. In contrast, Todd's asexuality is the only other satisfying sexuality in the show, if satisfying means once he achieves a sexual subject position he makes it possible to attach without being physically or emotionally threatened, nor abusing anyone — to be clear, this is not the only way to describe asexuality, but it is BoJack Horseman's way. Repro-narratives in Todd's own family make him bitter and aggressive; intimate companionship without sexual complication makes him loyal, attentive, and calmer. There is a high correlation for all of them between having desire and confronting the impossibility of intersubjectivity. [⤒]

- I learned the useful and powerful phrase "unconscious on parade" in conversation with Sharon Willis at Cornell in the 1980s. [⤒]

- I speak here of the form of self-shattering in love described by Jean-Luc Nancy, in The Inoperative Community, translated by Lisa Garbus, Michael Holland, Peter Connor, Simona Sawhney (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 1991), 82-109, which is almost antithetical to the self-shattering famously described by Leo Bersani in "Is the Rectum a Grave?" in Is the Rectum a Grave? And Other Essays (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 3-30.[⤒]

- The connection between the capacity to bear frustration and to generate thought occurs throughout his oeuvre, but to begin, see Wilfred R. Bion, "A Theory of Thinking," in Second Thoughts: Selected Papers on Psychoanalysis (1967; London and New York: Routledge, 2018), 110-119.[⤒]

- See Lauren Berlant, "Structures of Unfeeling: Mysterious Skin," in International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 28, no. 3 (2015), 191-192.[⤒]

- Later in one of the episode's meanwhile plots, Penny says, "I want something good to come of what happened." This echoes Diane and Princess Carolyn's discussion about writing something, anything, that will let injured girls to feel less alone. Stories take you out of the situations to alter-world meanwhiles where freedom drives, justice judgments and play can be speculated into engendering better consequences and more generosity toward errors. [⤒]

- The telephone in "Good Damage is a linking object not just because it reaches other people in a simple sense of attachment, but because Diane is more secure about her relations to the world across intimate distances and uses media like the telephone and the screen to create a cushion that spares her from being in the room and being seen in relation to her whole body and her appetites. The idea of a linking object is associated broadly with different concepts of attachment, but the usual emphasis is on one's implication in the object (one's internal sense projected onto it). Typically, discussions move from the loved/hated maternal object of Melanie Klein to W. R. Bion's investigations into the psychotic subject's violence when the dissociative order they've made of the world is attacked by the collapse of divisions between things that needed, subjectively, to stay separate. That boundary collapse produces "linking," which for these subjects is overwhelming. See Melanie Klein, "A contribution to the psychogenesis of manic-depressive states," in Melanie Klein, ed. Love, Guilt, and Reparation and other works 1921-1945 (1937; New York: Macmillan, 1975), 262-289; and W. R. Bion, "Attacks on Linking," in Second Thoughts, 93-109. For a more affirmative view of play and violence with one's objects, see D.W. Winnicott, "The Use of an Object and Relating through Identifications," in International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 50 (1969): 711-716. A decent summary (but there is no good review essay) might be Peter Fonagy and Mary Target, "The Rooting of the Mind in the Body: New Links between Attachment Theory and Psychoanalytic Thought," Journal of American Psychoanalysis 55, no. 2: 411-456.

Diane's internal objects take quite a thrashing in the meanwhile of her constantly self-undermined and destroyed analog home movie, at least until she writes her way out when a new stand-in for a person and therefore a new narrative arc appears. [⤒]