New Literary Television

Edited by Arin Keeble and Samuel Thomas

Introduction

Among the most prominent features of contemporary "prestige" television are a new set of relationships with "the literary." There is a striking tendency in recent television to foreground acts of reading, writing, and storytelling as well as research, publishing, and what we might call, with some caution and qualification, "literary culture." In addition, many of these shows build narratives through and around eclectic, often eccentric webs of literary allusion that eschew old hierarchies of genre and form. Largely uninterested in the cultural capital that literary allusion might be said to afford, contemporary television is using literary history as an open archive toward a range of ends.

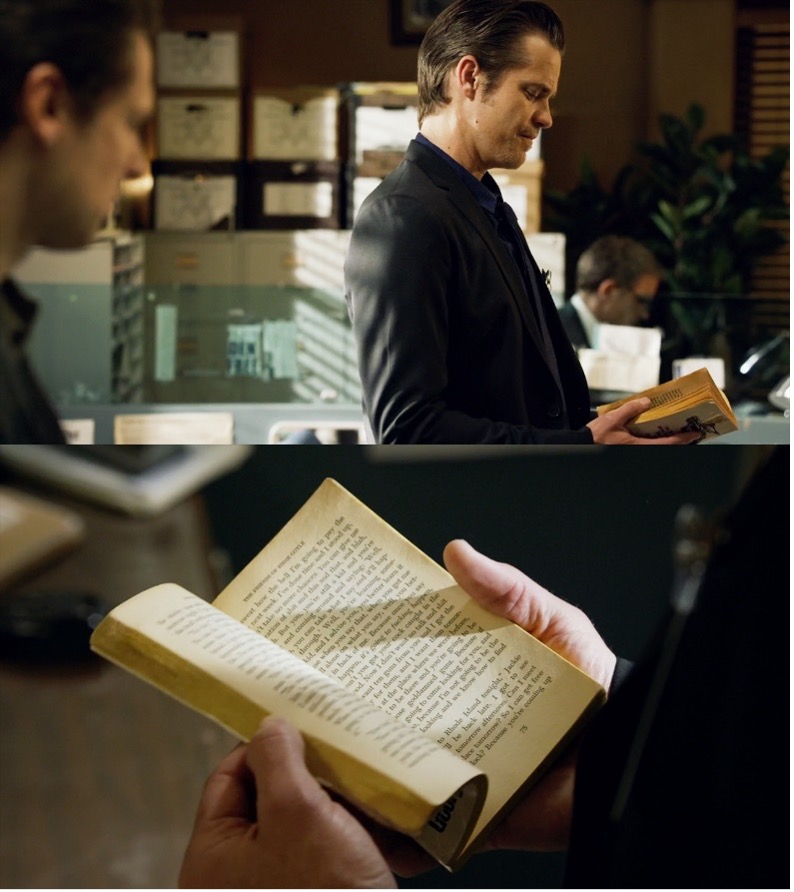

Think, for example, of the eye-catching moment in the final episode of FX's Justified (2010 -2015) in which Deputy US Marshal Raylan Givens, on departing Kentucky, hands a well-thumbed copy of George V. Higgins's The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1970) to his colleague Tim Gutterson:

Raylan: "If I say I've read it 10 times, I'm low."

Justified, season 6, episode 13, "The Promise" (2015).

On one level, this functions as a cute and subtle tribute to the late Elmore Leonard (the show's guiding spirit in various senses), who credited Higgins as a transformative influence. It also, however, points to accumulated debates about genre classification and cultural value that the show both inherits from and leaves behind (Leonard, always comfortable with the tag of "genre" writer, called The Friends of Eddie Coyle "the best crime novel ever written," without knowing that Higgins strenuously resisted being described in such terms).1 And it ultimately, looking back across Justified's six seasons, becomes part of a much broader tapestry of reference points and influences. These range from principal antagonist Boyd Crowder reading or quoting authors as different as Somerset Maugham, Mark Twain, and Isaac Asimov, to the intersecting literary and labour histories of Harlan County (the show's key setting in rural Appalachia), a place visited and written about by Theodore Dreiser and John Dos Passos, for instance, during the famous miners' strikes in the Depression era.2 We begin with this brief example not only because — cards on the table — watching and discussing Justified played a significant role in developing the friendship that came before our editorial collaboration. We do so also because it neatly communicates this cluster's central concern. The pieces here all consider the ways in which a diverse range of shows raise and address questions about the place of "the literary" in contemporary culture — and, more fundamentally, about what "the literary" is, who it is for, and why it matters.

The nature of the relationship between prestige television and literature (particularly the novel), has been debated since this new kind of TV emerged in the late 1990s.3 Most of these debates have focused on the alleged literariness of longform televisual storytelling, though increasing attention has been given to influence in the opposite direction, too.4 For instance, a recent article in The Atlantic, "The Rise of Must-Read TV," proposes that a sort of "option aesthetic" is emerging in contemporary fiction: a proliferation of works that feature "episodic plots, ensemble casts, and intricate world-building," thus (strategically?) inviting "a move from the printed page to the viewing queue."5 Nevertheless, the majority of the discourse remains skewed toward the perceived literary qualities of TV. David Simon has figured very prominently in these discussions since pitching The Wire (2002-2008) to HBO as a "novel for television." Simon's public persona as a writer, first and foremost, shaped the perception of a series celebrated for its complex, slow-burning narrative arcs, its extensive network of characters that move in and out of focus, its exacting social vision, and a set of memorable literary allusions. The journalist Joe Klein's suggestion, quoted in Lorrie Moore's review of the DVD boxset, that The Wire would be a worthy recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature, and the rapid appearance of the show in the syllabi of English Departments, boosted this particular conception of "literary television". But Simon's claims for the literary qualities of The Wire have been variously contested. Linda Williams, for example, persuasively reads the revered show as melodrama and notes that Simon "has certainly created great television but is not a particularly insightful critic of his own work."6 Nevertheless, The Wire's association with "the literary" has proven hard to shake and it is one of many examples of prestige TV that have been understood in this frame of reference.

Technological change has also fanned the flames of debate about the relationships between the literary and televisual. In The DVD Novel (2012), Greg Metcalf argues that the box set format turns episodes into "chapters", engineering "a novelistic sense of reading [ . . . ] that build[s] toward [ . . . ] the end of the 'book' of the DVD set."7 Some elements of Metcalf's argument have been rendered moot by the precipitous rise of streaming and the corresponding decline in DVD sales and production, a shift humorously registered in Justified when Raylan explains a Coen Brothers allusion to a fellow Marshal by quipping: "Netflix it, you can be one of the cool kids" (season 4, episode 1, "Hole in the Wall"). However, as Ariane Hudelet notes in her contribution to this cluster, the notion of an episode as a "chapter" remains a prevalent conceit — an indication of an enduring tendency to engage with television using literary concepts and terms. The rise of streaming and the dawning of the age of the algorithm have altered but not exactly slowed debates about "literary television."

That being said, a key tenet of more recent discussions has been an emphasis on the unique formal potential or "medium specificity" of prestige TV as distinct from the novel or the literary more generally. Jason Mittell, in the much-cited Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling (2015), strongly argues that "cross-media comparisons obscure rather than reveal the specificities of television's storytelling form."8 Elliot Logan's book on Breaking Bad (2008-2013), published in the same year, echoes this. Logan reads the New Mexico-set tale of meth, mayhem, and masculinity in crisis as a work that poses a broader argument for television's "fragmentary" seriality, which for Logan is "intentionally composed of, and understood as, episodes and seasons, each of which is a 'fragment' — 'something complete in itself and yet implying a larger whole.'"9 Others have argued for the formal uniqueness or exclusivity of prestige television while openly questioning its co-option by literary scholars. Michael Szalay, for instance, echoing Williams, asserts that "[q]uality serial TV comes from soap operas and melodrama, notwithstanding the efforts of English professors to liken it to the novel."10 So here we see a very tangible pushback, as it were, against the configuration of literary-televisual relationships exemplified by the initial framing and reception of The Wire.

While these discussions provide important context for this cluster, with several of our contributors directly engaging with particular aspects or phases of them, we need to be clear that coming down on this or that side of the fence is not at all what motivated us in bringing these essays together. Instead, we take Phillip Maciak's argument, that there is an "unmistakeable romance" between the literary and the televisual in the early twenty-first century, as a usefully suggestive jumping-off point. From here our focus is on contemporary television that we believe depicts new and different kinds of literary practices, on contemporary television that is literary-aware in new and different ways.11 This wave of TV is distinct from earlier prestige programmes that frequently and self-consciously sought to align themselves with the cultural status of the novel. Instead, the shows covered in the cluster's eight pieces treat literary history as a layered and contested resource or archive. This is simultaneously more substantive and more creatively diffuse than, say, the nods to Whitman and Shelley in Breaking Bad, to O'Hara and Kerouac in Mad Men (2007-2015), or to Fitzgerald in The Wire. Indeed, the shows that constitute this new literary TV are often as invested in popular and/or pulp genre traditions as they are in literary canons (Justified, the show we opened with, borrows from and reinvents a panoply of well-worn tropes from the Western, the Southern Gothic, and the police procedural). And as we've already noted, these shows are mostly uninterested in mining the literary for cultural capital. They are far more likely to engage with what that capital actually means — implicitly and explicitly reflecting on the cultural politics of the literary/genre divide and dramatizing how race, class, and gender impact on literary production under neoliberal capitalism. They situate themselves within literary landscapes in ways that comment on the inherent contradictions behind certain well-worn and resurgent national myths. The emergence of the "new literary TV" therefore suggests new kinds of interplay between narrative media and new kinds of small screen social vision.

Getting more specific, two strands of what we call the new literary television are discernible in the cluster. One can be said to concentrate on literary practices — on contemporary acts of reading, writing, interpreting, research, and publishing, inside and outside of various institutional and professional contexts. The other can be described in terms of an emphasis on the patterns and processes of citation, allusion, adaptation, and genre.

With the first of these strands in mind, Diletta De Cristofaro's essay looks at how Gilmore Girls: A Year in the Life (2016) revises the image of the literary "achievement subject" so vividly constructed through the figure of Rory Gilmore (Alex Bledel), identifying a corrosive entanglement of literary culture and neoliberal entrepreneurial selfhood. Sheri-Marie Harrison considers authorship, agency, and the commodification of Black female trauma in Michaela Coel's I May Destroy You (2020), exploring how the show tracks powerful shifts in literature-as-industry (especially vis-à-vis social media and identity politics). Rachel Sykes also reflects on the depiction of contemporary publishing, demonstrating how Younger (2015-), builds a resonant critique of the corporate/literary workplace while simultaneously perpetuating its own fantasy of a lucrative, glamorous career for white millennial women. Arin Keeble's essay, in useful contrast, examines how Lodge 49 (2018-2019) gives us a more positive image of literary practices. Lodge 49's investment in an "everyday" literariness that structures and connects the lives of its characters, it is argued, points to a kind of sanctuary from the existential and material threats of unemployment and precarity.

The second strand here covers overlapping yet distinctly different territory. Maisha Wester's essay on Lovecraft Country (2020) explores how the series responds to the erasure of African American histories, recuperating and reinscribing them via literary allusion and citation. Addressing the same show from a different perspective, Stephen Shapiro's essay focusses on Lovecraft's Country "disobedience" to both the novel it is based on and the novel per se. Despite the ubiquitous literary references, Shapiro claims, Lovecraft Country can be understood as a rejection of the novel's authority that proposes an alternative cultural history in which the Black Arts movement of the 1960s is centrally important. Ariane Hudelet, approaching literary television from the field of visual cultures, engages with Fargo (2014-), another genre-rooted show, and considers how its multiple intertexts and paratexts generate compelling questions about the nature of storytelling across media (thus helping to bridge the two stands). Finally, Andrew Hoberek's essay on Lupin (2020-) argues that the French Netflix production is "literary" in a rich variety of ways while at the same time completely side-stepping the literary trappings conventionally associated with US television, going on to explore some of the political implications of the show's plot-centric "amoralism."

So there's nothing here on The Handmaid's Tale (2017-), The Plot Against America (2020), The Man in the High Castle (2015-2019), The Underground Railroad (2020), and so on. Or, for that matter, on Game of Thrones (2011-2019). That isn't to say that the new literary television, as we have conceptualized it, might sometimes relate to and/or function as a kind of meta-commentary on these kinds of page-to-screen adaptations. However, we believe that the "romance," returning to Maciak's term, between the literary and televisual, is most compellingly expressed in ways we have outlined and is exemplified by the shows under discussion in this cluster. It's our pleasure to share these essays with you.

Sam Thomas (@lit_metal) is Associate Professor in the Department of English Studies at Durham University. He is a specialist in US fiction, particularly the work of Thomas Pynchon. His research interests include crime and political violence, the literary/genre divide, and metal music and culture. He is the author of Pynchon and the Political (2007) and various journal articles.

Arin Keeble (@KeebleArin) is Lecturer in Contemporary Literature and Culture at Edinburgh Napier University. His research interests include the literary and cultural representation of terrorism and crisis, neoliberalism and systemic violence, and punk culture. He is the author of Narratives of Hurricane Katrina in Context (2019) and various journal articles and book chapters.

References

- David Boeri, "George Higgins: The Teller of Boston's Stories," WBUR News, October 23, 2009.[⤒]

- For an excellent overview of Harlan County's place in literature see Alessandro Portelli's They Say in Harlan County: An Oral History (Oxford University Press, 2011), 242-246.[⤒]

- There are numerous appraisals of the emergence of the so-called "golden age of TV." Philip Maciak's essay "The Televisual Novel," which we cite elsewhere here, is particularly good at showing how a new set of shows emerging in the late 1990s "reoriented audience expectations and caused a sea change in the way that networks — broadcast and cable — perceived their development processes." See "The Televisual Novel," in American Literature in Transition 2000-2010, edited by Rachel Greenwald Smith (Cambridge University Press, 2018), 89. [⤒]

- Maciak's essay, mentioned above, also discusses this in particular relation to Jennifer Egan's A Visit from the Goon Squad (2011), said to be influenced by The Sopranos. See also Michael Szalay, "The Author as Executive Producer," in Neoliberalism and Contemporary Literary Culture, edited by Rachel Greenwald Smith and Mitchum Huehls (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2017), 255-276.[⤒]

- Alexander Manshel, Laura B. McGrath, and J. D. Porter, "The Rise of Must-Read TV," The Atlantic, July 16, 2021.[⤒]

- Linda Williams, On The Wire (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 3.[⤒]

- Greg Metcalf, The DVD Novel: How the Way We Watch Television Changed the Television We Watch (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2012), 7. [⤒]

- Jason Mittell, Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling (New York: New York University Press, 2015), 18. [⤒]

- Elliott Logan, Breaking Bad and Dignity: Unity and Fragmentation in the Serial Television Drama (London, UK: Palgrave, 2015), 17. [⤒]

- Michael Szalay, "Melodrama and Narrative Stagnation in Quality TV," Theory and Event 22, no. 2 (2019), 466. [⤒]

- Maciak, 88.[⤒]

Past clusters

Abortion Now, Abortion Forever

African American Satire in the Twenty-First Century

Contemporary Literature from the Classroom

Ecologies of Neoliberal Publishing

Feel Your Fantasy: The Drag Race Cluster

For Speed and Creed: The Fast and Furious Franchise

Keywords for Postcolonial Thought

Leaving Hollywoo: Essays After BoJack Horseman

Legacies — 9/11 and the War On Terror at Twenty

Minimalisms Now: Race, Affect, Aesthetics

Mobilizing Literature: A Response